| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Winsor McCay |

|

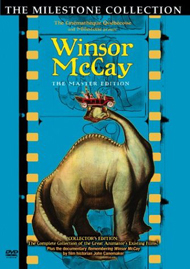

Winsor McCay The Master Edition Milestone 1911-1921 / B&W / 1:37 flat full frame / 105 min. / Street Date June 1, 2004 / 29.99 Starring Gertie the Dinosaur(us), Little Nemo, Flip, Impie, John Canemaker Original Music Gabriel Thibaudeau Collection Produced by The Cinémathèque Québécoise and Anke Mebold Directed by Winsor McCay |

Milestone's carefully-assembled DVD is a collection of most all of the extant Winsor McCay animations between 1911 and 1921, including his famous Gertie the Dinosaur which I've only seen previously as a fragment.

McCay was a self-made movie sensation who helped screen animation come to life by not only transposing popular comic characters but by working with the film medium itself. Many of his jokes flirt with film vs. reality ironies.

A master draughtsman, McCay animated much of his work on paper instead of cels, requiring the painstaking redrawing of the entire picture for every frame. Gertie the Dinosaur romps on a background that constantly ripples, as it's a new drawing eighteen or twenty times a second. In the beginning his characters work on a silent movie proscenium, but soon we have plenty of action that moves and revolves in depth. The quality of his animation still impresses the experts. The sequence in which Gertie walks forward gives an almost perfect illusion of motion on the Z axis.

Gertie is a good example of early multimedia thinking, an extension of magic-lantern shows that worked with a live host explaining images as they came up. For his dinosaur movie, McCay (or a substitute working from a script) stood to the right of the screen with a basket of pumpkins. He read the lines as if asking questions of the giant dinosaur, which then nodded and performed other responses. When it came time to stop Gertie's crying, the emcee threw the pumpkin behind the screen, hopefully timed with the animated pumpkin that lands in Gertie's mouth. And then the emcee walked behind the screen, appearing on it as the animated human figure at the end of the cartoon. The early exit of the emcee allowed him to change costumes if he was needed in the next act!

Apparently audience reaction in 1914 was sensational, as if they accepted Gertie as a real and living monster. More importantly, by giving Gertie happy and sad emotions, the audience empathized with her the same as they would a human actor. 1 I may be mistaken, but I believe I told in Bob Epstein's UCLA lecture that the original cartoon had no intertitles and relied on the live actor alone to keep the "story" on track.

McCay also used his skills to produce "documentary records" that were sort of early-silent "amazing recreations" of events that news cameras couldn't film. His Sinking of the Lusitania with early movie propagandist J. Stuart Blackton is a clinical "true" exposé of the German U-boat attack. In its day it was taken just as seriously as Oliver Stone's JFK. Some shots of the U-boat appear to be rotoscoped from live action, a device McCay would experiment with later. Audiences were treated to the sight of women and children perishing in the cold Atlantic. The terrible war between bickering monarchies was thus "spun" as a fantasy of virtuous allies fighting a demonized Hun enemy.

How the Mosquito Operates is an excellent depiction of the insect's mechanical device to suck blood, leavened with some morbid humor. Little Nemo comes complete with its original hand-coloring. Centaurs is a tame but advanced experiment in rotoscoping (tracing, essentially) live action figures and combining them with original animation.

Many of the later films show McCay entering a fantasy world by using the repeated "dream of a rarebit fiend" concept for motivation. Welsh Rarebit was a dish that old wives claimed caused dreams and nightmares, so in popular entertainments was used as a couth substitute for the theme of drug addiction, then a polite taboo. Each short shows a couple in bed wondering if they'll dream. In The Pet an oddly-shaped animal grows to outlandish size and starts eating buildings, much as in Tex Avery's later King Sized Canary. The husband in The Flying House turn his homestead into an airplane for a nicely-drafted series of flying scenes over the countryside. Since he seems to be trying to ignore his nagging wife, the dream plays as an unconscious desire to escape one's marriage. McCay apparently blows cigarettes smoke over his animation stand to effect "dream" dissolves.

One educational remnant is a McCay roughcut of episode with a circus-like animal. It's really raw animation camera footage, with constant blackboard inserts instructing the editor to insert title and dialogue cards, and to cut out bad frames shot by mistake. Very instructive.

Extremely helpful is the inclusion of a full-length audio commentary from animator John Canemaker, who explains what McCay was going for when the cartoons themselves don't tell us. There's also an 18-minute featurette with Canemaker called Remembering Winsor McCay in which he describes his early friendship with the animation pioneer and the importance of the artist's work.

Milestone's DVD of Winsor McCay The Master Edition is easily the best resource yet compiled on the pioneering animator. Almost all the clips on view are in better shape than most remaining short subjects from the era, and this is the first time I've seen Gertie presented wide enough to catch all the gags that happen around the periphery of the frame. Just when things seem pretty tame, Gertie snags a Wooly Mammoth by the tail and flings it about a mile or so into the background, and one has to laugh out loud.

The B&W line drawings have good contrast, and the frequent live-action inserts are also well-preserved. Gabriel Thibaudeau's music provides solid accompaniment, helping along the sometimes protracted logic of McKay's Rarebit Fiend dream sequences.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Winsor McCay The Master Edition rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Good, very good for material of this rarity

Sound: Excellent

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: May 24, 2004

Footnote:

1. The Gertie setup

must have made an impression on Buster Keaton, who took the "enter the screen" idea to its

technical ultimate in Sherlock Junior. Tossing the live-action pumpkin and having it replaced

by an animated one is a switcheroo beautifully exploited by Ray Harryhausen whenever he has

monster-fighters throw rocks or spears at his animated critters. Audiences in the 50s and 60s didn't

think Harryhausen's creatures were real, exactly, but we accepted the screen magic as innocents not

yet jaded by CGI manipulations.

Return

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |