| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

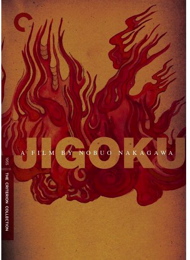

Jigoku

|

||||

Although great works of art have described the fires of Hell at least since Dante Alighiere's Divine Comedy, films have given us relatively few glimpses of Hell outside of satirical comedies. Films blanc like Ernst Lubitsch's Heaven Can Wait often picture Paradise and Hades as bureaucratic waiting rooms. When the flames of Hell find more direct expression, as in the rather confused 1935 Dante's Inferno with Spencer Tracy, the experience usually turns out to be a dream, with visuals cribbed from classical paintings or the engravings of Gustave Doré. Souls in torment wave their arms like modern dancers, and wailing victims appear to be imprisoned within trees and fused with rocks. Americans have always been familiar with hellfire & brimstone church sermons, but movie representations of Hell are most frequently found in cartoons. Depicting the tortures of the damned in a live-action film was almost impossible after the Production Code came in. An ordinary toilet wasn't allowed on-screen until 1960's Psycho, and making jokes about Hell could be equally jittery. In Robert Wise's 1963 The Haunting Russ Tamblyn is shown a classical engraving of a scene from Hell and quips that it would make perfect artwork for a Christmas card. Americans had no idea how extreme was Japanese exploitation filmmaking in the late 1950s. Less prestigious Japanese companies churned out crime films more cynical and violent than anything seen in the west. Japanese horror pictures added explicit gore to rigidly codified ghost tales about betrayed lovers becoming ghosts and murder victims transforming into demon cats. The Shintoho studio augmented its low budget nudie films with a string of ever-bloodier horror product, some of the most notable of which were directed by industry veteran Nobuo Nakagawa: Vampire Moth, Black Cat Mansion. Nakagawa's last film for Shintoho, Jigoku, translates literally as "Hell" and is a thematic leap beyond, both in subject and style. Jigoku arrays an assortment of partial nudes under its main titles, pointedly making us conscious of our own impure interests. The first two-thirds of the story unfold in a modern setting stylized to express a cruel logic of guilt and tragedy. The final third depicts an appalling afterlife that offers no hope whatsoever, a terror-vision of grotesque and gory images completely unacceptable on western screens.

Jigoku's most shocking aspect is its nihilistic view of existence. Professor Yajima's lecture ("Concepts of Hell") surprises us with the information that many religions and not just Christianity believe in the existence of a Hell; the scheme pictured here is the Buddhist model. The kinds of morality plays we see in American literature and film tend to be of the Young Goodman Brown school, where curious innocents learn the path of Virtue by catching a glimpse of the alternative. In folksy fantasies like Cabin in the Sky or even a George Pal Jasper Puppetoon, relatively minor sins like gambling or sloth invariably lead to utter chaos with the Devil biting at one's heels. More often than not the sinner discovers his experience has only been a bad dream. Thus chastened, he hurries back to the proverbial Straight and Narrow. This pattern fits fantasies both trashy and sublime, from A Guide for the Married Man to Eyes Wide Shut. 2 Jigoku never heard of atonement. Its wailing songs and poetry preach only one lesson: We're all sinners, we're all damned, and there'll be Hell to pay. All humanity is marked by an Original Sin that cannot be erased. Shiro and Yukiko have had sex out of wedlock. It makes no difference that they love one another. Shiro isn't responsible for the hit-and-run of the drunken gangster, but it doesn't matter. His 'friend' Tamúrá functions like a vindictive conscience. Like Edgar Allan Poe's William Wilson, Tamúrá may represent Shiro's suppressed malevolence, his 'evil side.' Tamúrá never explains how he knows privileged information: Yukiko's pregnancy, Professor Yajima's unsavory behavior in the war. Director Nakagawa frequently isolates Tamúrá with eerie colored lighting, leading us to assume that he is a Devil's envoy sent to lure Shiro to damnation, a suspicion the film doesn't confirm. The cynical Tamúrá is as human as anyone else, and suffers right along with them. All mortal sins are equated in this universe. No distinction is made between intentional poisoners and heartbroken suicides, or between passive negligence and active malice. The 'Earthly' segment of Jigoku culminates in an absurd series of bizarre deaths that take down the entire cast. 1 Nakagawa's Hell is an almost random array of ghastly, garish visions laid out in widescreen tableaux. A minimalist design scheme dominates. The Styx-like Sanzu river is merely a foggy band of mist cutting through a velvet-black frame, and various fumaroles of fire, lava and other boiling liquids stand ready to receive the damned souls from the earlier section of the film. One unpleasantly colored receptacle is described as filled with "human pus." As the victims are all screaming in agony, close identification of our earlier cast of sinners is sometimes difficult. But it really matters not, as this is an equal opportunity Hell -- a horribly special fate has been prepared for everyone! When Jigoku was finally imported for U.S. screenings, horror genre cognoscenti were quick to realize that its gory visions predated the supposed 'first' American gore offerings of Herschel Gordon Lewis. Nakagawa throws a number of images in our faces that certainly match American gore porn of the 1960s. A saw slowly bisects a human trunk and a screaming victim is instantly turned into a bloody mess of exposed organs. 3Weirdly, even in Hell Shiro is still able to debate the dismal state of affairs with Tamúrá. The opening narration stated that Hell punishes those that escape Man's law, but what we see doesn't play like fair retribution. Shiro and Yukiko must bear witness to the fate of their unborn child, which will forever float away on the river, crying in the darkness. We're told that children who die before their parents are left in Limbo, but Shiro and Yukiko are now dead as well, so the logic of this cruel cosmic technicality escapes us. By the time the abrupt ending arrives, the film has become an abstract dreamscape. Shiro is given an odd binary vision of Yukiko and Sachiko that suggests a faint ray of hope, but Jigoku's final impression is one of unrelieved despair. Criterion's DVD of Jigoku is a good enhanced transfer of an element with slightly soft colors -- until the underworld segment, when flaming pits and oceans of hands reaching for help splash the screen with stark primary hues. Disc producer Marc Walkow began work on the title over two years ago, when Criterion was planning a second branded label called "Eclipse" to handle genre cinema. The focus was eventually changed to include more general overlooked and lesser-known cinema, a category for which Jigoku certainly qualifies. Eclipse hasn't been abandoned altogether, but both this film and Equinox were re-routed to the standard Criterion banner. Nobuo Nakagawa's Ghost Story of Yotsuya (Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan) was acquired at the same time and so may appear in the future. The special features include a trailer, a selection of colorful posters for both Nobuo Nakagawa and Shintoho releases and a helpful insert essay by Asian cinema expert Chuck Stephens. The revealing interview docu Building the Inferno is a terrific look at Nakagawa, Jigoku, the development of the Shintoho studio and Japanese horror in general, featuring interviews with actor Yoichi Numata, screenwriter Ichiro Miyagawa, other Nakagawa collaborators and modern J-Horror director Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Jigoku rates:

Footnotes:

1. Oddly, the only similar demise in Western films happens two decades later in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, when another dinner party is wiped out by tainted fish. And it's a comedy.

2. There is a curious mini-genre of tiny (about 2" by 5") American comics, each using a different narrative gimmick to reach the same conclusion: The reader needs to accept Jesus Christ as his Lord and savior or face a judgment condemning him to the fires of Hell. The comics are designed for purchase by evangelists, to be left on bus benches for students and other young people to find. Some are crude and others well drawn, and some are even funny. In more than one comic, a 'cool' character tempts the hero to compromise his immortal soul, and is later revealed to be an agent of Satan.

3. Amusingly, this horror-view of a man regarding his own denuded rib cage and beating heart is framed almost identically to a (bloodless) scene in a Warner Bros. cartoon: Bugs Bunny wakes up, thinks he's been 'skeletonized' in a like manner, and starts bawling!

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |