Film Restoration and Preservation 2010

by Richard W. Haines

A DVD Savant Guest Article

Note: In response to an error I made about the Technicolor process in a DVD Savant article, author and filmmaker Richard W. Haines wrote me a long and informative note covering some common misunderstandings about film preservation. I asked Richard if he'd like to expand the note a bit for use as a DVD Savant Article, offering to review his exacting reference book Technicolor Movies. This is the result. As with all of Richard's writing, it's well-informed, clear and to the point. -- Glenn Erickson

In 1992 I wrote an article for The Perfect Vision magazine (Vol. 3 No. 12) entitled, Restorations or Alterations. It examined the work that was being done by archivists like Robert A. Harris to restore classic motion pictures. They used photo-chemical methods which involved re-printing surviving elements onto low fade triacetate intermediate stock in a wet gate printer to remove base scratches. The results could be very impressive as illustrated in the 70mm re-issues of Lawrence of Arabia and Spartacus. However, there were limits to this technique. Extreme damage could not be fixed and the long term stability of triacetate came into question.

Today films are restored in a completely different manner. Modern digital restorations can make many aging film negatives look brand new. Before detailing these techniques let's look at the history of film preservation.

Preservation Timeline

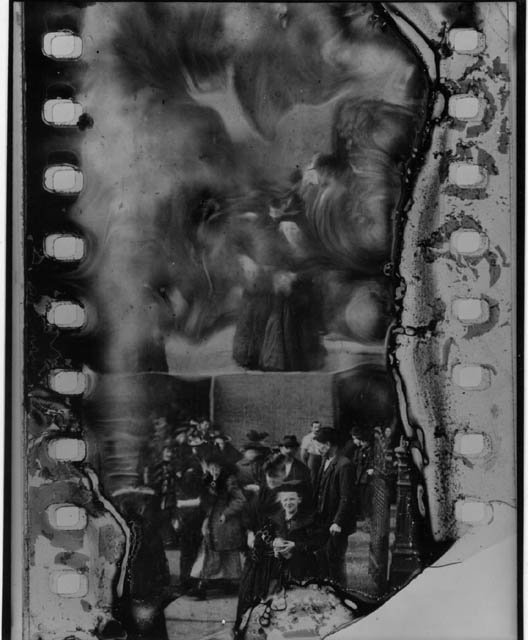

The concept of preserving motion pictures didn't start until 1948. That was the year Kodak introduced triacetate safety film to replace the dangerous and volatile nitrate stock in use since the beginning of cinema. Nitrate remains a very strange and mysterious plastic to archivists. In theory it had a very limited life span. While it generated a spectacular image in B&W and Technicolor it was made out of unstable materials. Nitrate is the explosive component of gunpowder. It can decompose in less than thirty years or last beyond seventy. Before deterioration it looks like a regular piece of film but in the last stages of decay it can crumble to dust or ignite.

Decomposing nitrate

Decomposing nitrate

The first question everyone asks is why would Kodak make film stock out of this material? The simple explanation is that film was never designed to be projected under carbon arc light. The original nitrate plastic invented by George Eastman was intended to replace the glass negatives used in still cameras and was safe for that application. When Thomas Edison and others started using the same stock for motion picture experiments it became more dangerous. A major fire would result if the film jammed in the projector gate -- a fire that could not be put out by water. There were sub-formats like 28mm, 16mm and 8mm that used less flammable diacetate 'safety film' but they shrank rapidly and were less reliable in the field than nitrate.

Motion pictures grew in popularity and were so lucrative no one wanted to rock the boat, so laboratories and theaters took precautions handling the dangerous film. Projectors had fire rollers in the magazines and were enclosed to limit the flame to the gate. Movies were printed in small thousand-foot reels rather than assembled onto large platters like today as a further safety measure. This is the source of terms 'one reeler' and 'two reeler'.

There weren't any methods of preserving movies until the late twenties, as duplicating film stocks didn't exist. All optical effects had to made in the camera by cranking in reverse and double-exposing to create dissolves or

superimpositions. Fades were made manually too. All prints were struck directly from the original negative, which rapidly wore out. For release in foreign countries, out-takes were often used to make a second nitrate negative. Important films often ran multiple cameras to yield (slightly different) additional 'original' negatives.

After sound was introduced it was discovered that making opticals inside the camera was no longer possible -- they needed to shoot a slate to synchronize the audio with the picture. A very poor quality duplicating stock was used to make 'short opticals' in sound films. What that meant was that they used the original camera negative until there was an effect. Then they cut in the fade or dissolve, and then cut back to the original negative, all within the same shot. This caused an obvious drop in visual quality. B&W fine grain masters were made from the original nitrate negative to make mediocre quality duplicate negatives for foreign release.

In the late thirties an upgraded fine grain master stock for duplicate negatives was introduced. Most domestic prints were still struck directly from the original camera negative, putting wear on them, but at least there was a fine grain print as a backup. For sound films multiple nitrate elements were made, which included the camera negative, fine grain master and a duplicate negative for foreign markets. On silent pictures all that existed was the camera negative. Technicolor movies were shot with three B&W nitrate negatives in the camera but no backup elements were manufactured since the release prints were struck from "matrices", which were printing plates on film. For foreign territories the Technicolor lab would ship a set of nitrate matrices to England.

Finally in 1948 safety film with a triacetate base was introduced to replace the nitrate and diacetate stock. It took another four years before nitrate was completely phased out. The negatives of some films (1951's Show Boat, for one) contained both nitrate and triacetate film in its reels.

It was at this point in time that four individuals decided to take action to preserve their libraries. They were Walt Disney, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Louis B. Mayer. These producers could take advantage of this opportunity because they controlled their films. As the story goes, Mayer wanted to reissue an early MGM movie but was told by the lab that its negative had crumbled to dust. He contacted Kodak and was informed the nitrate was unstable and should be transferred to triacetate, a film stock that they estimated would last four hundred years.

What this involved was re-printing the original nitrate negative onto triacetate fine grain positive stock. From this element new 35mm or 16mm triacetate duplicate negatives could be made. Most of the nitrate negatives had picked up damage over the years, flaws that would be incorporated into the new triacetate safety master.

All four producers began their transfer programs. Disney and Chaplin only preserved movies in which they had a financial stake. Disney's early Alice cartoons and Chaplin's Mutual comedies were not preserved because they didn't own them. Harold Lloyd took a different attitude and purchased the original nitrate negatives of all of his work including the Lonesome Luke shorts and pictures he made for Hal Roach before he became an independent. While Disney was able to transfer everything, Lloyd had a fire which burned up the nitrate negatives on most of the Luke films. Fortunately his best features were saved.

Mayer ordered all of MGM's nitrates to be transferred to safety film but on a priority basis. The popular features were done first and the silents were slated for last since they had little commercial value at the time. MGM suffered nitrate fires in 1965 and 1976 that claimed many negatives, including most of the Buster Keaton silents, Laurel and Hardy's Rogue Song and Lon Chaney's London after Midnight.

Laurel & Hardy's only Technicolor feature was lost in a nitrate fire.

Laurel & Hardy's only Technicolor feature was lost in a nitrate fire.

The other studios were slow to react. To be fair, movies were considered a 'one shot deal' before the advent of television, like a stage play. Other than an occasional re-issue or Disney cartoon revival old movies were considered worthless inventory. Negatives were left to rot in storage or abandoned in labs that closed. It was very expensive to insure nitrate vaults so companies like Universal destroyed all of their silent movies in the late forties.The Goldwyn estate junked all of their silents except those starring Gary Cooper. Other nitrate fires resulted in major losses. A fire at RKO destroyed the Citizen Kane camera negative and another at Fox destroyed most of their pre-1935 movies.

The broadcast of film classics on television didn't happen all at once. The studio moguls considered television a usurping medium to be fought, rather than utilized as an ancillary market. Howard Hughes broke the ice in the mid-fifties when he sold RKO to General Tire, which licensed the library to C&C Corporation for broadcast. This proved so lucrative, the other studios finally gave in and sold their backlogs to TV as well.

Even the additional broadcast revenue didn't inspire the other studios to perform a complete transfer of nitrate negatives to safety. They did it slowly, but as Anthony Slide noted in his book Nitrate Won't Wait, many films decomposed before the studios got around to re-printing them. For example, by 1967 the original negative of Frank Capra's Lost Horizon had deteriorated completely. It had to be restored from a worn nitrate release print and a grainy 16mm print. The AFI was founded in 1967, with part of its mission the coordination of the preservation efforts of the studios and archives.

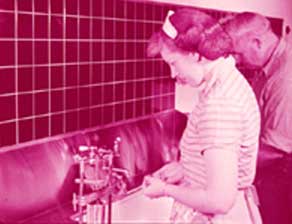

Faded Eastmancolor

Faded Eastmancolor

By the seventies the situation had improved and the studios had began to catch up on preserving the remaining B&W films. What helped was not only the expanding television markets but the growth of Repertory cinemas. Many cities had at least one revival theater to show old movies which in many cases were new prints made from the preserved safety masters. The Regency theater in New York City programmed themed festivals featuring the works of Preston Sturges and Alfred Hitchcock. But just as things were looking up the industry was hit with a new archival crisis... color fading.

In 1979 articles appeared in American Film and Film Comment magazines detailing problems with Eastmancolor negative and print fading. The color negatives deteriorated after twenty-five years and the prints began turning pink after only ten. In the case of dye transfer prints derived from Eastmancolor negatives, the release copies remained stable while the negatives lost their color.

Fade-proof "Glorious Technicolor"

Fade-proof "Glorious Technicolor"

After intense industry pressure by Martin Scorsese and archivists Kodak improved their Eastmancolor dyes and in 1983 introduced 'low fade' color negative and print film. All Eastmancolor negatives had to be re-printed onto low fade stock. Fortunately the emerging home video and cable markets gave an incentive to continue their preservation programs.

How Safe Was Safety Film?

The next crisis occurred a decade later: 'vinegar syndrome'. It was discovered that triacetate film that was processed incorrectly or poorly stored also deteriorated. Although it was less volatile than nitrate and would not explode triacetate tended to shrivel up while giving off an odor much like vinegar. Once deterioration began there was no way to stop it although films stored well were holding up better. Kodak's four hundred-year estimate of triacetate was no longer accurate. It should be noted that triacetate should be classified as potentially unstable as opposed to nitrate's inherent instability.

In 1993 an upgraded stock known as 'Estar' film was introduced for release prints and intermediates. In theory Estar should last at least seventy-five years or longer if stored correctly. Both B&W and Estar color stock are now used by the industry for all applications except principal photography, which continues to use the less stable triacetate film.

What are the ramifications of this development? In theory all surviving triacetate films should now be transferred to Estar as a backup element. This represents another huge expense for the owners of motion pictures. For modern features the costs can be included in the production budget. Each new movie will maintain the original camera negative on triacetate along with a color interpositive and set of B&W separations on Estar film. Since the camera negatives are no longer used for release printing they should remain in good shape. While that takes care of contemporary movies it still leaves the first eighty years of cinema in need of restoration.

Digital Restoration 1993-2010

Before continuing, let's skip back in time to 1993, a critical year for film preservation. Not only was Estar stock offered but a new method was developed to restore old movies. Walt Disney used to joke that his empire started with a mouse. I'll joke that modern restoration began with 'Disney dust".

When industry insiders went to see Jurassic Park they noted how seamlessly the digitally created dinosaurs matched the live action, without matte lines or other optical artifacts. Archivists at the Disney company wondered if similar technology might enable them to paint out the little colored specks of dust contained on the cell negatives in the multi-plane camera. They contacted Kodak, which developed a program to remove the dust on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The new 35mm copies were cleaner than the original Technicolor prints.

Other archivists began to examine the triacetate safety masters and noticed that a lot of wear was contained on the preservation element. By scanning it in they could remove these flaws. Early films that utilized this technology included Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes. The results were so good it was difficult to screen what was previously considered acceptable for the preservation of classics.

There were two types of digital restorations. One method was to scan in the nitrate negative (if it still existed) or the safety fine grain master then go through it on a frame-by-frame basis to fix the defects. From this digital video master they would output standard and high definition DVDs. However, the original still retained the defects. If a new format were introduced, it would have to be re-scanned from scratch.

A better method utilized on selected movies was to output a new 35mm color or B&W negative for the future derived from the restored digital tape. The new negative would be on durable Estar stock which would be the new master film element. This was done for titles like The Adventures of Robin Hood.

While digital restoration was a major development in film preservation, there still remained issues. The most obvious was the resolution of the digital master. Years ago they scanned movies at 2K which was considered acceptable for the time. Kodak then estimated that 4K was the minimum to replicate 35mm emulsion. That became the new standard used on movies like The Sand Pebbles. That feature was digitally restored at 4K and then out-put to 35mm Panavision. I screened a new Estar print and compared it with the Blu-ray and they were nearly identical in terms of quality.

But the bar was raised once again, by Warners. They digitally restored The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind by scanning in the original three-strip nitrate negatives at 8K resolution. The quality is so fine grain, it's like seeing both movies for the first time. There is more detail in the camera negatives than was apparent in original 35mm Technicolor prints. As spectacular as these 'full restorations' are one can see the dilemma faced by owners of vintage motion pictures. While 35mm has been the standard for over one hundred years, digital technology is like a moving target. No system or format lasts very long. Constant upgrades mean that film restoration and preservation will be a constant and ongoing expense into the future.

How Positive the Negative?

Now that you have a general background on this complex subject, let's look at what it takes to fully restore an old movie....

The first step is to do a worldwide search to find all surviving elements on the title. That includes original nitrate negatives, fine grain masters, duplicate negatives and prints on B&W movies. The reason prints are important is that some movies were censored over the years, especially Hollywood films made from 1930-1934, before the rigorous enforcement of the Production Code. Stricter Code rules in 1934 meant that movies like Frankenstein and King Kong had to be editorially censored to conform to the new standards. Both of these titles were eventually restored from surviving prints. Prints are also critical for silent movies since in most cases the negatives decomposed long ago. Complicating pre-1930 movies is that there were at least two original negatives. As a result there are different takes and sometimes different scenes in the same movie depending on the source of the print. It often takes a judgment call on which is the definitive version. This was one of the problems encountered during the restoration of Metropolis, before a surviving full-length reduction 16mm dupe of the original Lang cut was found in 2008.

After securing all known materials the archivist has to examine them for differences and condition. Then each usable element must be digitally scanned at a minimum of 4K. Depending on the movie it might have to be done on a shot-by-shot basis to make it complete. Once a full sequence is in the computer are a number of programs can be used including 'dust busting' and 'scratch removal' tools, along with progams that stabilize the image if it is shrunken or warped. After these have been applied additional work might need to be done on a frame-by-frame basis. Finally the film can be out-put to 35mm Estar base negative for the future as well as authoring it for standard and high definition DVD.

Color movies pose different challenges depending on the format. Three-strip Technicolor movies require each separate negative to be scanned, digitally cleaned and then superimposed to create a composite color image. Eastmancolor negatives need to be color corrected to restore faded dyes. If the camera negative is too far gone then restorers must use the B&W separations, the backup elements made for many Eastmancolor titles. These are similar to the three-strip Technicolor negatives except they are fine grain positives of each color rather than negatives.

Other problems with old Eastmancolor negatives are the grainy opticals. The poor color duplicating stock of the fifties resulted in the use of the same 'short optical' technique done on sound films made in the thirties. These opticals were often fairly dusty, so aside from trying to improve the grain structure to match the original negative shots they might have to paint out the printed-in dust.

In 1955 Technicolor abandoned the three-strip camera for principal photography and switched to Eastmancolor. But they still used the fade-proof dye transfer process for release printing. Original Technicolor prints, if they exist, are a valuable reference for restoring the Eastmancolor negatives. But there are other complications. Beginning in 1955 Technicolor began to A & B roll the original negative so they could make the fades and dissolves directly onto the matrix stock and avoid grainy duplicating film. In the early sixties they used an auto-select process for the same effect, to avoid the double A & B rolls. The entire shot would be included on the camera negative and the fades and dissolves would be made in the printer only. That means every fade and dissolve in a film printed in this manner, must be re-created from scratch for the digital restoration.

Non-conventional negatives are another difficulty. Facilities had to customize digital technology to restore films shot in 65mm, 35mm horizontal VistaVision, 2-sprocket Techniscope and even 55mm. which Fox used for The King and I and Carousel.

Perhaps the most complex digital restoration was Warners' work on the three-panel Cinerama epic How the West Was Won. That feature was shot in Eastmancolor with release prints made in the dye transfer process. Even when projected properly the process was very flawed. The panel joins were obvious and the color often didn't match between the prints. Warners' impressive digital restoration scanned in the three separate negatives, digitally cleaning them up and matching the color between each panel. The panels were then morphed together into a seamless widescreen image. The Blu-ray was an incredible achievement that surpassed the original in terms of blending the separate films.

Working from the original negative generates the best-quality transfer but is also the most expensive method. Camera negatives are not 'timed' -- not color-corrected or, for B&W, contrast-adjusted. Each shot must be timed separately when they the image is inverted from a negative to a positive. The second best quality source will be a 'first generation' color interpositve or B&W fine grain master. Both are low contrast materials made directly from the camera negative and already timed. Theatrical release prints are high contrast rather than low contrast and therefore not ideal. But if that's all that exists, that's what the transfer technician will have to deal with. Prints tend to have more wear and will require a frame-by-frame digital clean up, adding to the costs.

Phony Restorations

Some video companies use the terms 'restoration' and 'preservation' as a marketing scam. Silent films are especially subject to restoration claims. Only a handful of titles have been fully restored, including Keaton's The General on Blu-ray and Chaplin's City Lights & Modern Times and Kino's Metropolis in standard definition. You'll find boxed sets of famous comedians that claim they are restored but in reality they just transferred the materials they had which vary in quality.

Other than Chaplin and Lloyd, most silent films are derived from surviving nitrate release prints, not negatives. As a result they need extensive restoration to be made presentable. On the other hand, silent movies were so poorly preserved that many are a 'work in progress', as is the case of Metropolis, which has just been restored by combining previous excellent-quality scenes with the new material discovered in a poor-quality 16mm print unearthed in South America.

While we can give some leeway to the way silents were presented in the past due to the limits of photo-chemical techniques, after the digital restoration of The General, scratchy and worn copies of silent classics will no longer be acceptable. Be especially wary of public domain companies that release worn dupes of these movies.

Film Collecting

I've heard many film collectors and movie buffs complain about how many copies of the same movie they have had to purchase over the years on VHS, laserdisc, DVD and Blu-ray. The usual question is "Why can't they get it right the first time?" While I sympathize with their concern it's not entirely fair to blame the distributors. Digital technology keeps improving as do restoration and preservation techniques. Would you rather watch the old DVD of The Wizard of Oz or the new Blu-ray?

Cinema buffs will have to face the same problem as distributors. Restoring movies is an ongoing process and collecting your favorites will not be a one-time purchase. Fortunately, DVDs are relatively inexpensive and still cheaper than two people seeing the movie in a cinema. All things considered they are a great deal and an excellent format for watching movies.

May 18, 2010

Richard W. Haines is a film director and historian. He wrote the books Technicolor Movies and The Moviegoing Experience 1968-2001 for McFarland and Company as well as articles for The Perfect Vision and Film History magazines. His notable feature films include Space Avenger (1989) printed in the dye transfer Technicolor process in China, Run for Cover (1995) in 3-D Stereovision and his latest horror movie, What Really Frightens You (2010).

Text © Copyright 2010 Richard W. Haines

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 2010 Glenn Erickson

See more exclusive reviews on the Savant Main Page.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Also, don't forget the

2010 Savant Wish List.

T'was Ever Thus.

Return to Top of Page

|