|

|

|

|

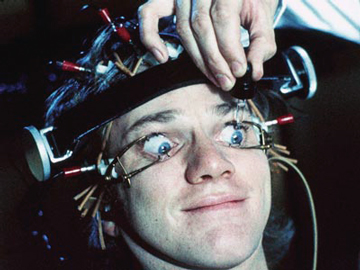

A Clockwork Orange is so saturated into the consciousness that it scarcely needs an introduction. If you haven't seen it and are coming to Savant for the basic lowdown, A Clockwork Orange is Stanley Kubrick's low budget investigation of youth violence, taken from the very good novel by Anthony Burgess. All the dialogue is in a futuristic argot Burgess invented called nadsat, a curiously easy-to-understand lingo that blends Shakespearean English with Cockney slang and some Russian-sounding words (that's a gross simplification). The leader of a mob of delinquent "droogs", Alex DeLarge (Malcolm MacDowell) ditches school and dresses in a frightening costume to rob, beat and kill innocent citizens. Addicted to "ultraviolence", he takes on another gang engaged in raping a captive girl. Alex is eventually betrayed by his pals and sentenced to 14 years in prison. He attempts to find a quick road to a pardon, first by cozening the prison chaplain, and then by volunteering for a radical psychological experiment intended to make him incapable of committing further violent crimes. The Ludovico Treatment turns out to be brutal aversion therapy, a brainwashing scheme advocated by a repressive government to neutralize all forms of anti-social activity. As a film student in the 1970s, the only movie that I truly thought was a pretentious fraud was The Exorcist, and I've already exorcised my own resentment toward it in this column. I've never really liked A Clockwork Orange, but Savant readers won't have to put up with another tirade because I've softened on it considerably. The extras on various Warner special editions have contributed to my rehabilitation. I don't believe that A Clockwork Orangeis the best filmic statement of its theme, but as an artistic work, it's quite uncompromising.

Kubrick had spent almost half a decade making an enormously complicated and technically groundbreaking personal statement about man and space and destiny, and for his next project he wanted a major change. Filmed as a low-budget endeavor, A Clockwork Orange conveys its unpleasant near future with carefully chosen locations, not gigantic sets. Its future is a cinematic construction, an extrapolation of then-current trends. Kubrick's future sees the triumph of awful, ugly taste in just about everything -- the victory of the consumer society has molded a docile public living in plastic squalor. The very rich like Mr. Alexander have swank country estates, but the average citizen lives in a concrete housing block, in rooms barely big enough for their intended functions. Public art is insipid and the video-reared populace has little concept of higher values. Most of the art and even the decorations are based on crude erotic imagery -- the prevalent image in paintings and sculpture is of women with legs spread-eagled. We're confronted by one hideous interior after another, worse than the purposely nauseating "average American abode" in Theodore Flicker's The President's Analyst. But Kubrick doesn't stop there -- A Clockwork Orange is purposely, relentlessly ugly in its cinematic forms. As if produced to be consumed in this ugly future, there are no subtleties, no grace notes, nothing elegant or sensual. Compositions are straight on, blatant. Wide angle lenses dominate. Kubrick adapts pop-art aesthetics for his montages and transitions, using flicker cuts and flash cuts. To express the wicked and violent fantasies in Alex's head, we see a flurry of explosions, disasters, violent moments, flicker cut with Alex as a fanged vampire to assure us that he loves the violent fantasy, revels in it, and fantasizes himself as its monstrous, delighted instigator. As is every egocentric punk with delusions of importance, Alex is the over-confident center of his private violent world. Most everyone else is a grossly exaggerated distortion in both appearance and acting style. Truant officer Mr. Deltoid (Aubrey Morris) minces and grins, like a Lewis Carroll grotesque. Michael Bates' prison martinet is a screaming, goose-stepping exaggeration of an exaggeration. Only those who wield violence are presented naturalistically -- they're the only people Alex feels are even alive, including his clueless father and simpleminded Mum. She's at least 50 but dresses like a silly preteen, and is an appalling sight. A Clockwork Orange presents its concepts in an intentionally klunky, overstated, obvious style. Mr. Alexander can't just segue into a seizure-like mindstorm, we have to cut repeatedly to him rolling his eyes and frothing at the mouth. Every story point is belabored, as if the audience were abject morons. This was what I objected to in 1971, as the film seemed to be insulting my intelligence. Nothing is ellipsed and little is skipped. Alex goes through a progression of scenes in which he dishes out terror, pain and suffering until he is caught, and is later on sent through a reverse series of torments and retributions, in an exact symmetrical reverse order. Messages were being hammered home long after they'd been received and acknowledged. I felt the same about the sinister Ludovico Treatment, and the broad message that the government's oppression was just as wrong and pernicious as Alex's freelance hooliganism. I spent a great deal of this 137-minute movie saying, "I get it already, why are you doing this to me?"

Well, the reason is that Kubrick's artwork is designed for a futuristic audience. He keeps cutting back to the rape victim's body on display for the camera because the jaded future audience really wants to see a lot of that, like the rationed steak in a wartime Tex Avery cartoon. The gang rumble is a collection of rather stupid action stunts, stuck together like a string of wham-bam sausages. None of this is filmed with any point except to give the viewer a good, clear aid to action-film masturbation. It's super-exploitation, visual pornography. Kubrick and Burgess make this idea explicit in the films Alex is shown during his aversion therapy -- there's a TV channel for sex and another that shows non-stop beatings and cruelty. (The tightly focused one-subject, one-channel idea is like our present cable TV, which very efficiently fragments the viewing public. It's succeeded in splintering us politically, too.) A Clockwork Orange isn't Network; Burgess and Kubrick aren't trying to predict a specific future. The exaggerations are a comment on England of 1971, which the newspapers represented as a nation under siege by lawlessness. The other reason I rejected A Clockwork Orange in 1971 was that I didn't think it had anything new to say. I was familiar with brainwashing movies so that was no revelation. Even in my first years of college I didn't see youth violence as an isolated phenomenon but as a symptom of poverty, unemployment and a society without meaningful goals. No prospects? Let's raise hell. And I've always been a champion of Joseph Losey's brilliant These Are The Damned (1961), an articulate and poetic statement that equates the ugly crimes of youthful hooligans with the bigger and more sinister terror programs of official governments. These Are The Damned was and probably is still obscure, but it's the kind of visionary film one can warm up to: at one point the voice of authority lectures an American liberal, saying "The Age of Senseless Violence has caught up with us too." That moment of prophetic insight has more resonance for me than all of A Clockwork Orange.

But now I acknowledge that Kubrick's film is a different animal with a different agenda; it's a genuine artistic statement by another kind of visionary. Even the film cuts in Clockwork are grating, violent -- like the bright red screen that cuts to a blue one in the titles, assaulting all those little rods and cones in our eyeballs. Kubrick respects his source, and proves that (with a little visual help) the screwball nadsat language can be understood by us Nuddly wudlicks. 1 Warner Home Video's Blu-ray of A Clockwork Orange nails the transfer at an in-your-face 1:66 aspect ratio, and looks exactly, exactly as I remember it at a press screening in December of 1971. The high-key lighting of some interiors and the please-back-off-another-foot close-ups of pink 'n' white pimply faces grinning at us are dead-on accurate. Yep, those flicker frames that too closely resembled interesting sex are still missing from the Keystone Kops afternoon threesome in Alex's bedroom. This version is rated "R". Dolby and DTS tracks are here, along with audio and subtitles in English, French and Spanish. This time around Kubrick goes for selected needle-drop music by Wendy Carlos, Beethoven and Singin' in the Rain sung by Gene Kelly. That's probably another factor about A Clockwork Orange that initially burned me -- using that song to make Alex's ritualized rape even more outrageous. I was a huge fan of that musical in 1971, so Kubrick was in a way giving us complacent film fans the Ludovico Treatment, too! The Anniversary disc has extras new and old. The new items are in HD but aren't very substantial, if only because the ground was so well covered before. Malcolm McDowell flips through some artwork in search of memories for one featurette, and recites an Alex DeLarge speech at the beginning of another featurette that calls on a number of directors to say profound things about how our present day world has become like the violent world of Clockwork. I've never bought that rubbish. Step away from the heavily developed rich countries that can afford efficient police forces, and the world that 70% of the Earth's people live in is a semi-lawless chaos, where the official protectors can be as vicious as the bandits that do everything they can get away with. Besides, the premise of Clockwork and These Are The Damned is true -- war is a constant state in many places, for all sorts of reasons nobody wants to be particularly honest about. The older extras are very good -- I learned a lot about a movie I'd purposely avoided. Producer Nick Redman's commentary with Malcolm McDowell is pleasant and informative, while two long-form making-of docus reference plenty of A Clockwork Orange crew people to fill us in on its genesis and production. Excellent spokespeople (like BBFC censors) explain the film's post-release history. Shown uncut as a Certificate "X" release (don't tell me that Kubrick's reputation didn't affect the decision), Clockwork was withdrawn from English distribution by its director two years after it opened, and never reissued in that country until after Kubrick's death. Other bits make a case for A Clockwork Orange as an unforgettable super masterpiece, an assessment that doesn't sway me but doesn't offend me either. They certainly can prove that the show contains more than its share of original and influential imagery, and the stories of Kubrick are always interesting. The original trailer is also here. Its design was the height of radical editorial style in 1971. A second Blu-ray disc contains the previous documentaries Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001) and O Lucky Malcolm! (2006), both by Jan Harlan. The first is a career overview; it's 142 minutes just by itself. O Lucky Malcolm! is another long form piece on the film's star. Both are quality productions.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

A Clockwork Orange Blu-ray rates:

Footnotes:

1. Nuddly wudlicks. I made that up, and it sounds more like something from Winnie the Pooh. Actually, I'm still working on understanding George Harrison's "grotty" from A Hard Day's Night.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2010 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||