DVD Savant

Interview

Article by Stuart Galbraith IV

Sci-Fi Savant is DVD Savant's first book in seven years, a collection of 116 chronologically sorted reviews, spanning Fritz Lang's Metropolis to James Cameron's Avatar. Director Joe Dante puts it best: "When it comes to classic sci-fi movies it's rare to find much in the way of new insights. But Glenn Erickson [DVD Savant's alter-ego] ... has gathered together ... a treasure trove of ideas, opinions and research that'll entertain you for hours."

Its contents include obvious genre mainstays like Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but also myriad enticing obscurities such as director Abel Gance's (Napoleon) The End of the World (1930), an early French talkie; Cosmic Voyage (1936), a Soviet epic about a trip to the moon; and Bertrand Tavernier's Deathwatch (1980), about a popular reality TV show that surreptitiously films people as they die.

Glenn Erickson on the spfx set of CLOSE

ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND

Stuart Galbraith IV recently sat down with the Rondo Award-winning Erickson for a chat about the new book, sci-fi films generally, and the genre's trends then and now.

Stuart Galbraith IV: Why not a book on Euro-Westerns, MGM musicals, or Hong Kong action movies? Why sci-fi?

Glenn Erickson: I looked back and saw that all of those genres had been discussed from multiple angles by very knowledgeable authors. The full spectrum of science fiction movies hasn't been surveyed in quite a while. We've got one excellent research and opinion book about the years 1950-1962 by Bill Warren, and an interesting encyclopedia edited by Phil Hardy, and that's about it for serious literature. The really incisive fantasy film writing these days is in horror, but the premiere journal Video Watchdog hasn't much interest in classic Science Fiction. In SCI-FI SAVANT I try to elevate the status of the genre for audiences who think that sci-fi started with Blade Runner (1982). I give attention to pictures that we core followers of the genre couldn't see growing up, ones that were never distributed in the U.S. for political reasons.

Galbraith: Why do you think that is, that there's this strong emphasis on serious scholarship of, say, the horror films of Mario Bava or Terence Fisher, but not the science fiction films of George Pal or Ishiro Honda?

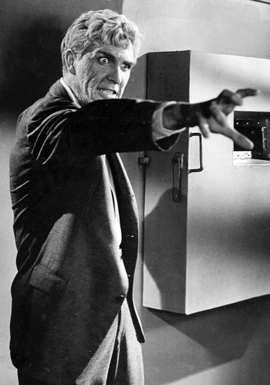

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS

Erickson: Horror has a longer and more respected tradition that reaches back into literature, folklore, religion, and great art of all kinds. Science fiction is the bastard child of 20th century daydreams about fantastic, yet very possible futures. Horror was judged by its best films, and praised as the work of creative artists. The upstart sci-fi genre was content-driven, and mostly elicited jokes about purple people eaters and monsters that ate Cleveland. Raymond Durgnat and Susan Sontag touched on sci-fi films for a major article or two, but only rabid auteurists staking out new territory would write up articles like "The Desert Movies of Jack Arnold." Until 1968, sci-fi was not the place for a director to make a high-class reputation. Did anybody ever interview filmmakers like Rudolph Maté, Irving Pichel or William Cameron Menzies? Roger Corman was considered a fast-buck artist while making his imaginative little sci-fi pictures, and recognized as an artist only when he turned to Edgar Allan, creaky coffins and swinging pendulums. But none of the Poe pictures or his acid-trip movies is as cinematically original as X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes. "Important" filmmakers tended to tap the genre for a masterpiece or two and then stay the hell away: Howard Hawks, François Truffaut, Joseph Losey, Jean-Luc Godard, Stanley Kubrick. Sci-fi is a fun place to let one's imagination run wild, but nobody wanted to be typed as a sci-fi director.

Galbraith: What was the first sci-fi movie you saw in a theater? What was that experience like?

Erickson: I'm not sure which came first. I wasn't born quite early enough to see most of the 1950s classics when they were new. At age seven I started attending matinees of The Return of the Fly, Teenagers from Outer Space, and Gigantis the Fire Monster. We lived on Hickam Air Base in Hawaii and the streets were so safe I could walk to the show by myself. That was a real break because nobody in my family wanted to see monster movies; I attended most of these pictures alone. The first bona fide "Matinee" experience for me was The Mysterians. I was impressed by the other shows but this one had an entire audience of Air Force brats cheering our lungs out. It even showed the aircraft our fathers flew, with the markings of M.A.T.S. (Military Air Transport Service).

Galbraith: As you got older, did you ever venture out to some of the more specialized theaters in Hawaii and on the West Coast, such as the Japanese-language movie houses owned by companies like Toho and Shochiku?

CHIKYU BOEIGUN (The Mysterians)

Erickson: I became aware of the Kokusai and Toho La Brea theaters but didn't follow their schedules. As I never had any money, I shied away from the "see everything" habit and so missed unique engagements. I learned about the original Japanese version of The Submersion of Japan only when Bill Warren wrote it up for Cinefantastique. When I did pay full ticket price at the Japanese theaters, it was to see a Sword of Vengeance movie. Those things thrilled and scared me at the same time.

Galbraith: Why is it that if you're a fan of, say, '30s screwball comedies you're a cineaste with taste, while those with a fondness for '50s sci-fi pictures are mere fannish geeks? How come we don't get any respect?

Erickson: It's probably because there's some truth to the stereotype. Most of us began as imagination-hungry introverts, eager for the spectacle and excitement of Sci-fi. We were only partially socialized. That means that as kids we connected with our friends on the basis of shared interests - movies and monsters, often. At UCLA I organized several screening series of fantastic films (an excuse to run Ray Harryhausen pictures) and a very popular sci-fi series in full 35mm in the best theater on campus. Students and kids would ask fannish questions and make immature remarks that annoyed me. I felt embarrassed when one hippie-ish kid who stared at the floor a lot sat me down and made me look at his collection of original press books. I thought I was more mature than him, but I was really just a fan-snob. After a showing of The Incredible Shrinking Man where I was forced to screen a fairly ratty 16mm copy, the hippie said, "Gee, I wish I knew you didn't have a 35mm print. I could have loaned you mine." The guy I dismissed was a more committed fan than I was. He was friendly and outgoing while people surely thought that I was the geek. So I changed my act and started appreciating movie fans.

Galbraith: If I counted correctly, Sci-Fi Savant offers 116 movie reviews, of which almost half are from the 1950s, when the genre really exploded for the first time. Why are people still so fond of that era?

QUATERMASS 2 (Enemy from Space)

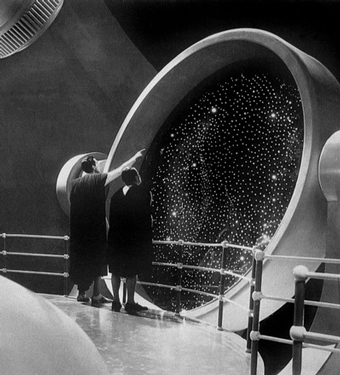

Erickson: I think that the overall complacency factor was far higher in the '50s. The mass audience was less complicated, mainly because people and opinions outside the mainstream were ignored or marginalized. People believed whatever they heard on the news. There was an illusion of consensus on most issues, and the relatively small group of folks that didn't conform was considered either interesting eccentrics or dangerous thinkers. Fifties sci-fi films offer a fantastic break from the norm, yet they still believe that "normal" exists. Their frightening threats to society are almost always resolved with a return to the status quo: "Earth. Thank God it's still here". The audience enjoyed being made anxious about giant ants or Things appearing from the skies, and only when the genre discovered real paranoia did things become more complicated. I wanted to concentrate on the '50s because most of the main themes start there. After 1960 or so, the really original Sci-Fi pictures begin to thin out. What comes later are either refinements on good earlier work or purely derivative movies that may or may not even be entertaining. Also, the '50s pulp fiction romantic "dreams of the future" were quickly outdistanced by reality. The space program doomed movies about fanciful spaceships with swept-back fins. The technological violence being used in new wars and 'police actions' made most monsters seem less threatening than they once did.

Galbraith: And although the decade had its share of classics, fans seem equally drawn toward the genre's worst films, movies like Cat-Women of the Moon and Plan 9 from Outer Space. Why is that?

Erickson: Now this is getting personal! Sci-fi monster films became popular in the first decade that independent filmmakers had a realistic chance of seeing their work on a big screen. That meant that features could be made by people who didn't have an uncle in the film business. Budding geniuses, no-talent hacks and aging B-picture veterans rubbed shoulders, all looking for ways to hit the jackpot with a no-budget quickie. Cat-Women may be pathetic but it got a major release, in 3D. Affectionately maladroit items like Plan 9 had to wait to find an audience on late night television. Kids that scoured TV Guide looking for arcane discoveries (Fire Maidens of Outer Space, what's that?) practically adopted these movies. Making a good movie isn't easy. The inanities of Missile to the Moon are downright humbling: when the production values we take for granted in Hollywood fare are missing, we begin to look beyond surface considerations. What were the filmmakers thinking? Was anybody really trying? The big surprise is discovering great ideas hidden in movies that nobody even remembers - except lazy modern sci-fi films, which rip them off: Terror from the Year 5000, 4D Man, The Crawling Eye.

4D MAN

Galbraith: Yes, but what is it exactly? I don't think those of us with a fondness for, say, Robot Monster necessarily enjoy it because we can scoff at its inadequacies. And while your question - What were they thinking? - certainly comes to mind, I'd argue that people like Ed Wood and Phil Tucker and even journeymen like Edward L. Cahn and the like, and certainly the actors and special effects guys and so forth, genuinely tried their best to infuse these super-cheap pictures with distinctive, entertaining, and/or original elements. Sure, there are pictures here and there where it's pretty clear nobody associated with the film really gives a damn - most of the films of Jerry Warren, for instance - but maybe those are the exception instead of the rule.

Erickson: I'm sure that most of these filmmakers put their hearts and souls into their work! Maybe this is a better answer: we genre movie fans respond to modest little pictures because we fantasize making them ourselves. It's therefore exciting to see somebody with no resources except their imagination give it a shot. Phil Tucker probably personally hauled the Ro-Man suit up the hill to Bronson Caverns, and Tom Graeff lugged around his homemade sound equipment for Teenagers from Outer Space. All of these directors had something going for them, even if their movies were laughed off the screen. We fans identify with this kind of Z-movie effort.

Galbraith: As you point out, after the fifties the ongoing, thriving genre sort of disappears. Instead of regular Harryhausen and George Pal and Roger Corman sci-fi pictures, instead it's almost like there's this fork in the road. The genre splits into two distinct groups: ultra-cheap sci-fi potboilers and big studio films like Fantastic Voyage and Planet of the Apes.

Erickson: Well, what ultra-cheap potboilers are you talking about, Charles Band pictures? The thriving genre you mention was always 80% low-end efforts. The big studio films of the 70s rarely had strong ideas or bold storytelling - we'd rush out to see things like The Neptune Factor, Futureworld or even a Planet of the Apes sequel and end up feeling cheated. The later Apes sequels really catered to the undiscriminating, and kids. Sci-fi requires original inspiration and something special. All the good ones are unique to their specific context. Star Trek movies are fun because of the personalities of the star cast. But 80% of the time, they function like submarine movies.

Galbraith: Growing up I was especially enamored of the genre of the late-'60s through about the mid-'70s, in mostly ambitious, socially conscious films, most of which seemed to star Charlton Heston. Why were studios so willing to make serious science fiction movies then? Desperation? And why not now?

THE TIME MACHINE

Erickson: We all love the movies we saw from, say, age seven to age 24. I'm older than you so I remember happy matinee experiences with The Time Machine, Voyage to the End of the Universe, and Godzilla vs. The Thing. John McElwee's chart in the back of the Sci-Fi Savant book explains why '50s sci-fi remained a small, if attention-getting genre: most of the big movies didn't make any money, and runaway hits among the small pictures were exceptions to the rule: The Blob, Rodan. Leading into the era you remember so well, Planet of the Apes came along and made an enormous fortune. This was a godsend to Charlton Heston. Just as his career was starting to fade, he was suddenly bankable in far-out movie ideas... so producers came up with far-out movies for him. Because it was a mainstream book success, Michael Crichton's The Andromeda Strain got a strong publicity push from Universal. The same studio delayed and then dumped the wonderful Colossus: The Forbin Project because it had no built-in mainstream awareness. The marketers were asleep at the switch. Universal didn't realize that audiences primed by 2001 would have loved a movie about a sinister runaway computer. I was 25 when Star Wars arrived and the floodgates opened for yearly Sci-Fi atrocities from big studios. Ice Pirates! Megaforce! Solarbabies!

Galbraith: I know Bill Warren's seminal book about that era's movies, Keep Watching the Skies!, was a big influence on you, while your reviews as DVD Savant have been a big influence on Bill. What are some of your differences, both in terms of the way you look at the genre, and also in your writing styles?

Erickson: Bill Warren has a wide range of film knowledge and a long history as a critic. He was driven at an early age to learn everything he could about the classic sci-fi pictures. He's the man when it comes to the genre, as he's meticulously researched the making of our favorite pictures, uncovering fascinating production histories and making connections nobody else could. I read his original two-volume set of KWTS, got his number from a friend and spent twenty minutes on the phone telling him how much the books pleased me. Bill is a researcher and an essayist and he leavens his prose with a personal, nostalgic touch. I'm a reviewer-essayist, I suppose. I've found out a few things on my own but for hard facts rely on the work of writers like Bill Warren, Bob Skotak and Tom Weaver. If I have a special angle, it's my experience as a film editor - the way a movie is put together sometimes reveals the truths that a film director won't tell. I don't see that much difference between our writing styles. We both take the subject seriously and we both love to joke about the movies we like.

Galbraith: Of the movies covered in this book, which ones were the biggest revelations for you: movies you'd never heard of, never thought you'd see, or which because of the way they're presented on DVD and/or Blu-ray, really knocked you for a loop?

Erickson: Oh, every year I get excited about some great picture that had eluded me previously: the long three-movie version of Until the End of the World; Nebo Zoyvot, Ikarie XB-1. Way back in 1996 a friend working at Columbia showed me the newly-reconstituted long version of These are the Damned. I was truly thrilled.

GORGO

Galbraith: Name three sci-fi pictures not on Blu-ray that you're most anxious to see in high-def, and how they'd benefit?

Erickson: That's kind of a juvenile question, which means that it's very welcome! Who would have believed that a nearly complete Metropolis would surface, even if the condition was marginal? I'd love to see Gorgo again in good quality, and only Blu-ray could do it justice...

Galbraith: Boy howdy!

Erickson: ... It was originally Technicolor, filmed by Freddie Young who did Lawrence of Arabia, and on a big screen it looked simply astounding. It's nowhere to be seen these days in primo quality, even though VCI's DVD transfer gives it a good try. A Blu-ray of Things to Come would be wonderful, but only if some marvelous preserved long version popped up from Argentina or something. I guess my third choice would be a great HD transfer of Invaders from Mars. That title is long overdue, in my frustrated opinion. Only Blu-ray could display all those weird color values correctly.

Galbraith: What was the single greatest thing about the DVD revolution? Was it that it made pictures like Ikarie XB 1, Gojira, and The Damned available for the first time, in their original versions, and with often superb video transfers?

Erickson: That's the gist of it. Foreign laserdiscs were too expensive and had no subtitles, but DVD opened the floodgates to bizarre imports. Most were horror pictures but a number of hotly desired Sci-fi rarities slipped in like the original First Spaceship on Venus, Der schwiegende stern. I was blown away by the disc of Cosmic Journey. Seeing the rare Soviet pictures, all made in a brief window when the Russians were winning the space race, was a thrill. Somebody really ought to put those out here, along with Bertrand Tavernier's uncut La mort en direct (Deathwatch) and the Czech Vynalez Skazy (The Fabulous World of Jules Verne). Toho still owes us a deluxe Gorath. The list of movies I have yet to see and am most intrigued by is growing short. William Dieterle's original two-part sci-fi spy thriller Mistress of the World Part One and Two is on my radar. It stars Martha Hyer, Sabu and Lino Ventura! Another is the Russian political satire Silver Dust (1954). It was excoriated by the U.S. State Department as vicious anti-American propaganda. Sometimes the timing on these discoveries is a bit troublesome. I finally got my hands on a French DVD of Abel Gance's La fin du monde and found that it is longer and slightly more coherent than what I carefully described in the Sci Fi Savant book.

Galbraith: Sci-fi cinema of the '20s through the '50s often centered around the wonders of amazing new technologies. Today, amazing new technologies like CGI are being applied to movies, which seem to me to be designed as more visceral yet also more passive viewing experiences. What are your thoughts on this? Have these limitless special effects technologies come at the expense of a more innocent sense of wonder?

Erickson: Well, they've certainly taken some of the special-ness out of sci-fi. Fantasy films were once the almost exclusive venue for progressive special effects, but now ordinary movies can take place in completely artificial worlds. We see a man in a wheat field and no longer believe that the wheat was really that golden color or that any wheat was even present during filming. Stunts are now meaningless, as any action on screen can be effectively faked. Just the same, tastefully used CGI can be marvelous. I'd love to see upgraded remakes of some of my sci-fi favorites, but today's inane characters and homogenized scripting can ruin anything. I don't think anybody tries for a "Sense of Wonder" anymore except Steven Spielberg.

Now that computer technology has really altered life for most of us, we have to admit that sci-fi missed the boat on the Information Age. Movies didn't predict the Internet, and only The President's Analyst even jokes about the communication connectivity revolution that cell phones and other personal electronic devices have brought about. Maybe it won't be long before someone implants an "iCommunicator" in a human brain. Perhaps Man as a social animal will merge with his inventions, and develop a collective consciousness, like the alien unit-beings of Quatermass 2 or Clarke's (unfilmed) Childhood's End. That's about as deep as my thinking gets.

Galbraith: Was there a science fiction film that really disturbed you to the point where you couldn't sleep at night? Or perhaps one that changed your way of thinking in some fundamental way?

Erickson: Yes indeed, Fritz Lang's The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse. Around 1980 the Filmex exhibition showed it, and it hit me like the proverbial diamond bullet to the brain. The 1960 movie seemed to predict the paranoid James Bond world, where surveillance is power and conspiracies hide behind every aspect of normal day-to-day existence. I flashed on the revelation that the technological terror of the 20th century displaced all the old bugaboos with a full spectrum of modern anxieties, all of which are manifest in the pulp fiction works of politically-canted plays, novels, serials, certain gangster films, superhero comics and paranoid science fiction films. In different dress, the same themes emerge - depersonalization, political oppression through new technologies, the remote control of human beings through voyeuristic snooping and mind control propaganda. That's pretty much when I began watching sci-fi films in terms of their underlying political themes.

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON

Galbraith: One movie you don't review is Star Wars. Why? Was that a conscious decision? And what are your thoughts about Lucas's decision to suppress the original theatrical version all these years, and in the broader sense, for filmmakers to go back and alter their films?

Erickson: Yes, it was conscious. There's far too much print and brain matter expended on Lucas's fantasy space opera. I was around and about when parts of it were being filmed, because the Close Encounters effects factory was operating at the same time, and the two shops shared personnel. Lucas indeed changed the way movies were made, etc., but he's now more of a legend than a filmmaker, and the second wave of Star Wars pix are just awful. Great artists can be a real pain when they want to control everything in their work, including the audience. Lucas's endless revisions of Star Wars would be just fine with me if he kept the originals in good shape for posterity. Even Steven Spielberg is said to be removing the Lucas-like revisions inflicted on his original E.T.. Alter your movies all you want, but preserve the originals!

Galbraith: In your introduction you allude to an earlier time when seeing movies like Forbidden Planet or Crack in the World wasn't quite so easy as pulling it off the shelf and sticking it in the player. What's the farthest you've traveled, the latest you've stayed up, just to see one movie? (Confession: I once stayed up to watch The Atomic Kid, a movie that didn't start until 4:30am. It was a decision I lived to regret.)

Erickson: Well, I once sat through three Santo luchador enmascarado movies in a downtown L.A. fleapit waiting to see a horror film called Messiah of Evil. They didn't show it. The kinds of sci-fi films I wanted to see weren't projected anywhere. I guess I think more in terms of how long I had to wait to see certain pictures. When I started editing for MGM Home Video I got to see items like The Lost Missile and Riders to the Stars that hadn't shown anywhere I could find them in twenty years...

Galbraith: And counting! At least with regards to those two films.

Erickson: ...But even MGM didn't seem to have a copy of The Flame Barrier for viewing. Still haven't seen that one, even though I've been assured many times that it's nothing special.

Galbraith: For you, personally, George Pal or Ray Harryhausen?

Erickson: Equal emphasis. I introduced myself briefly to Pal at Filmex in 1975; he had an incomparably sweet and winning personality. The next year I got to talk to Harryhausen casually at a party and liked him as well. Pal's ambitious pictures always got me, and Harryhausen is still the master of a unique "lost art". You need to realize that when I get tired I'll relax by watching an old favorite. That means I've probably seen most of the movies by both of these men 50 times.

THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS

Galbraith: Rereading your reviews I was continually reminded how political and prescient so many of these films were, movies like Quatermass 2 and Soylent Green, even those that didn't entirely succeed from an artistic standpoint, or which were undermined by inadequate budgets. And it's very hard to imagine movies as direct politically being made today, unless dumbed-down a la movies like The Day After Tomorrow. Your thoughts?

Erickson: Gattaca and Children of Men are excellent pictures with plenty of smarts in the socio-political arena, but I don't believe either was a big hit. I'm more used to groaners like Sunshine (2007), which runs an interesting premise (our sun needs to be re-ignited) directly into the ground with a hopelessly lame bloody murder and madness spree. Plenty of movies have terrific production values, including great post-Ridley Scott industrial spaceship interiors never seen in the classics. And then they all turn into zombie movies.

Galbraith: Sci-fi movies of the past often presented a hopeful (and pro-science) future epitomized, one supposes, by the Star Trek franchise, while today almost all filmed science fiction seems negative, downbeat, and even anti-science. What do you think?

Erickson: Cynicism is easier to manage because optimism takes so much more work. I wish the spectrum of all entertainment would stop trying to chase the commercial target of the moment, and give us more variety. That could certainly include a movie about an invention or a trip into space or an alien visitor that didn't proceed directly to ho-hum jeopardy and mass killings. Just last year we were subjected to Super-8 and Cowboys vs. Aliens, a pair of imagination-challenged clones from the same derivative idea. I was bored to death. Rise of the Planet of the Apes does very nice things with its franchise reboot. It isn't deep, but it has a thoughtful, intelligent outlook. It's fun.

WELTRAUMSCHIFF 1 STARTET

Galbraith: Do you think Hollywood will ever get around to the notion that sometimes less is more?

Erickson: I keep waiting for a show to start with a card saying, "every shot in this movie was taken with a camera, with no computers involved." But I don't see things going that way. Special effects are slathered over projects as if that's the only thing spectacular action films have to deliver anymore. Nowadays Sci-fi movies are really action cartoons, crammed with cuts. They won't slow down for anything resembling a reasonable dramatic scene for fear of losing the attention of the desensitized audience. I really enjoyed Children of Men, but I could tell that some of the audience was impatient with it.

Galbraith: Over the past 25 years or so we've seen the work of directors like Roger Corman and Mario Bava reappraised. Is there anyone left in the genre waiting to be rediscovered? Can we look forward to Edward L. Cahn retrospectives in the future?

Erickson: Most of the makers of these pictures are still waiting to be discovered for the first time! A good study of George Pal would be welcome, I suppose. There's also a lot to be learned about a few European 'sci-fi auteurs'. I've never seen a movie by the prolific German Harry Piel. He directed and often starred in popular science-oriented fantasies during the early Nazi era, with titles like An Invisible Man Walks through the City, The World without a Mask (a TV set sees through walls) and Master of the World (a robot with a death ray). And we know next to nothing about the makers of the Soviet space movies. I'm hoping that Robert Skotak will publish a book of his researches on the subject. The propaganda in some of those Russian pictures is fascinating. In Sci-Fi Savant I write about a scene in Mikhail Karzhukov's Nebo Zoyvot that depicts decadent neon advertisements in Times Square, celebrating the capitalistic exploitation of Mars!

THINGS TO COME

Galbraith: Shamelessly stealing from Robert Weide: Without actually defending your choices, what's a sci-fi picture you always have to defend liking, and one you always have to defend not liking?

Erickson: I pretty much adore the turnip-cinema Creation of the Humanoids (1962) and nobody else will sit through it with me, not even my ever-patient grown offspring.

Galbraith: I would! I completely agree with you on that one!

Erickson: ...I think it's packed with those "prescient ideas" you're talking about, and the clumsy filmmaking only makes it more charming. I've never cared for the original Alien, which to me is an insultingly bad haunted house movie with great art direction. James Cameron's sequel, on the other hand, is a very exciting and intelligent experience.

Stuart Galbraith IV is a Kyoto-based film historian whose work includes The Emperor and the Wolf - The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune and special features for Tora-san

. Visit Stuart's Cine Blogarama here.

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 2012 Stuart Galbraith IV & Glenn Erickson

See more exclusive reviews on the Savant Main Page.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Also, don't forget the

2011 Savant Wish List.

T'was Ever Thus.

Return to Top of Page

|