|

|

|

|

Claude Lanzmann's Shoah is unlike any other Holocaust documentary. Other docus counterpoint survivor interviews with vintage film footage of the period, scripted content, authorial narration. The thesis is almost always sincere, but the presentation usually conveys a strong sense of a filmmaker attempting to produce something with a style. Setting aside crude exploitative efforts and TV "docus" concocted in a commercial environment ("...tonight's suffering is brought to you by..."), we're left with a core group of relevant films. Early efforts like Alain Resnais' short, compassionate Night and Fog were what was needed in the 1950s. The flood of movies exploiting footage of acres of corpses, etc., either stunned viewers into non-receptivity or generated an troubling desire to see more. Indeed, part of the horror of the average Holocaust documentary is that is will be consumed like any other filmed entertainment. Too many viewers will recognize the healthy Germans in their neat uniforms as people like them. The horrendous corpses and starved, staring victims are horrible to look at. They become the non-human monsters, something to look away from, to forget.

Shoah's Claude Lanzmann overcomes these problems by conceiving his film in completely different terms. At just under ten hours, it is in no way conventionally commercial. He uses no archive film at all. His film is all new footage, with the lengthy interviews (some inter-cut, some left completely as shot) interspersed with contemplative shots of modern locations -- parts of concentration camps, train lines still in use that once hauled "relocated" Jews, shots of various cities. The film is less a documentary than a purposely unmediated document. The interviewees speak German, French, Italian, Polish, English, Hebrew and Yiddish. Rather than rely on subtitles alone, or superimposing a different language over the speakers, Lanzmann shows us the interview just as it was filmed. Sometimes the speaker talks for thirty seconds and we have no idea what he's saying, until he falls silent and we hear the interpreter's translation in French. Most of the time, only the reiteration is subtitled. In other words, we experience the interview just as Lanzmann did. This ceases being maddening when we realize that further editing would introduce a director's selectivity, and perhaps allow deniers and scoffers to claim that the film was manipulated. Almost as importantly, as the subject being examined becomes more difficult to explain, we see the interviewee's reactions evolve. Part of the language barrier begins to fall away. Lanzmann is a tenacious interviewer. He has told his volunteers that he won't ease up on the questions, and he doesn't. Some of the stories that come out cause the witnesses to choke up. Explaining a beyond-appalling experience that he witnessed, a barber tries to excuse himself. Lanzmann won't let him. This 'say it all' technique takes time, but it lets us know the character of the interviewee and allows us more information to judge if they're telling the whole truth, or looking for sympathy, or grandstanding. The bottom line is that nobody is doing any of those things. As the interviews were made in the late 1970s, some of these people have waited 35 years to get the awful memories out of their system. Lanzmann insists on full detail. His question "How did you feel?" is said in earnest, not to provoke emotional scenes. The answer is usually, "I felt nothing. My emotions were deadened." Most of the witnesses were little more than kids back then, as was a boy used by the Nazis as a messenger. They were clearly chosen for their unique experiences. A couple of them were gas chamber workers ("everything had to be done at a run") that somehow avoided the murderous turnover process. One prisoner utilized in sort of a Judas Goat function tells a story of a comrade that tried to warn a woman prisoner he knew, that everyone in her group "would go up the chimney" in just a couple of hours. What happened, to her and to him, is the stuff of nightmares.

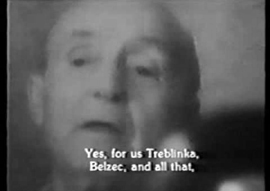

Many interviews are taken with Poles living outside the death camps, and even a train worker who delivered hundreds of thousands of Jews to extermination camps. One of these Christian locals has no trouble explaining that she got her house right on the town square when the Jew that owned it was rounded up. When a gathering of locals is interviewed together, the group dynamic brings out unexpected admissions. One pompous man makes a "diplomatic" statement about the tragedy of the Jews they saw being brought through town by the trainload. Barely a minute later, people are almost laughing as they explain how they warned the people in the trains by making "cut-throat" motions with their fingers. They claim it was a brave gesture of warning, but their attitude implies that they signaled the prisoners to amuse themselves, and that the memory still amuses them. Some of the best footage in Shoah was obtained by subterfuge. Lanzmann interviews two or three actual camp guards and SS men, that don't realize that they're being surreptitiously videotaped. Like proud businessmen, they detail the workings of the Treblinka death camp as if extolling the organization of a meat packing plant, eagerly pointing out how hundreds of people were "sent through the funnel" and processed in record time. Men are whipped into the gas chamber but the witness is reluctant to admit that the women are whipped as well. We learn how groups of 50 and 100 naked women and children were made to wait in freezing temperatures for their turn to be gassed. Another guard has remembered the words to a song that the prisoners at a work camp were forced to learn -- and sings them for us. "No Jew alive today knows that song," he proudly states. He's happy to be contributing to the historical record. I haven't seen or read anything that conveys this well the overwhelming hopelessness of the situation. Even in Marcel Ophuls' The Sorrow and The Pity and Hôtel Terminus we feel a rush of adrenaline when confronted with survived Nazis bragging of their accomplishments. Here in Shoah there seems to be no hope for anyone who hasn't bolted before the German clampdowns and round-ups. Big families have children that cannot be left behind or included in escape plans, so entire clans went passively to oblivion together. Even the helpless flunkies manning the gas chambers have no choice but to herd their own people to their deaths, in mass numbers. Survival is the only thought. Lanzmann doesn't build to a dramatic climax but instead ends his film with a quiet shot of yet another train moving through the snow toward its destination. Criterion's Blu-ray of Shoah comes on two discs, in four parts for ease of viewing: I've heard of marathon theatrical screenings but wouldn't attend one. The excellent transfer is based on a 4k scan of original 16mm elements -- we rarely if ever are aware that a smaller-gauge film format is being used. The track is very clear at all times, even in the stealth video excerpts. Subtitles are essential in a show of this kind, and two separate tracks are provided. One translates everything spoken, and another leaves the relatively few English passages in the clear.

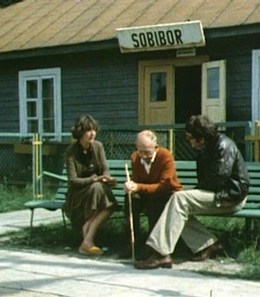

Three Claude Lanzmann documentaries are included. They were filmed with the Shoah interviews, but work better as separate items. The 102-minute Sobibor, October 14, 1943, 4 p.m is an extended interview with Yehuda Lerner, a participant in the famed Sobibor rebellion. He explains how, after two earlier failed break-outs, Jewish Russian soldiers familiar with weapons became prisoners and helped organize a plan to murder the guards and escape. Lerner's storytelling brings us finally to the moment when he becomes one of the few Jews out of millions, given an opportunity to strike back at the SS. The second docu The Karski Report is just under an hour long. Polish gentile and freedom fighter Jan Karsi was smuggled in to see the horror of the Warsaw Ghetto. He then undertook a mission to America to demand that the Allies do something to stop the total eradication of European Jews. Karski met with Franklin D. Roosevelt, who wouldn't listen and instead lectured him with abstract slogans. Told to visit a long list of Washington representatives and church figures, Karski met with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter -- a Jew -- who told him to his face that he didn't believe a word about Ghettos and extermination camps. The third docu A Visitor from the Living is an interview with Maurice Rossel, a Swiss Red Cross representative in Germany. Knowing that any formal request would be refused, Rossel took it upon himself to simply drop in at Auschwitz, and was received by its commandant. He was also part of an inspection tour of the Theresienstadt "Potemkin Village" arranged for outside observers, where prisoners were forced to pretend they were well treated. Rossel admits that his official reports do not reflect his honest opinion that the tour was a fake show. Lanzmann is interviewed about these short films, as is cameraperson Caroline Champetier and director Arnaud Desplechin (A Christmas Tale). In addition to an original trailer, an 80-page insert booklet contains two pieces by director Lanzmann and an essay by critic Kent Jones.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Shoah Blu-ray rates:

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with footnotes, reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||