| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

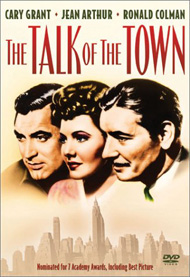

The Talk of the Town

|

||||

George Stevens made a long list of great pictures, and Talk of the Town is almost one of them. His conversion of a 'noble issue' drama into a romantic comedy is as adroit as can be imagined, and his stars churn what might have been a sticky talk-fest into entertainment as smooth as butter. Even more interestingly, Talk displays Stevens' political colors loud and strong: he's a liberal elitist, which in 1942 was not a bad thing to be.

The show starts with a disconcerting mix of styles. Leopold Dilg escapes from prison in a montage that looks clipped from a Fritz Lang film, with deep shadows and Cary Grant hiding behind a mask of feigned hardness. Then we jump into silly comedy, as everyone's sweetheart Jean Arthur juggles a crippled fugitive, a fussy professor, and assorted goofy townspeople. Nobody buys Cary as a desperate mug, and we also know that Ronald Colman's clipped snobbery will also thaw, so it takes a while for things to get going. The trio soon becomes a family, with soapbox agitator Grant charming Colman with his cynical rebuttals to the professor's lawbook formality. The arguments are halfway intelligent, so we stay fairly interested. Interestingly, when the movie gets into the big issues, it doesn't fall apart. Harboring a fugitive compromises the Court nominee, but he eventually sees his higher duty and goes outside the precise legal boundaries of the law to do what's right. The fact that he's doing this for personal friends (and a potential lover) is mitigated by Ronald Colman's screen presence. The actor oozes integrity and we believe every crooked thing he does - he lies, kidnaps and threatens people at the point of a gun. But always for a higher moral value, mind you. It's like Mahatma Ghandi playing Dirty Harry. Colman gave people a big surprise in the later A Double Life, by turning this noble screen persona on its head. The clever script has far too many climaxes, and starts off with comedy so unsteady that even pro Jean Arthur, running around in her pajamas all morning, has a hard time keeping things in balance. When they get into the meat of the story, the authors seem to be saying that good liberal thinking in this country (Colman) has to warm up to human needs if it expects to counter the avarice of landlords, factory owners and crooked politicians. In other words, there's no right or left, just Corrupt and Noble, and the Noble better get off their podiums and into the trenches to fight for what's right, or America is in trouble. It sounds great, but the end result is a little thin. Colman makes a short speech for apple pie while wrapping up the criminal mystery, the plot is resolved in another whirlpool of newspaper headlines, and then the film goes on for ten more minutes resolving the romantic triangle. I'll bet audiences loved it, but it's kind of drawn out ... one longs for the amazing finish of something like Laura, where a criminal is shot, the case is solved, the heroine cleared and the hero gets his girl, all in about 14 seconds flat. George Stevens' penchant for longer and deeper movies eventually led him to abandon Hollywood style films for epics that took 5 years apiece to get done. There's nothing flat about this film - there are fun scenes and characters and nice plot turns throughout. Leonid Kinskey (Casablanca) is a patriot who correctly informs on Dilg; I hope 1942 audiences didn't boo him, as the script certainly doesn't intend them to. Saucy Glenda Farrell (The Mystery of the Wax Museum) has a fun scene as a crooked manicurist that Colman easily trips up to solve the case. Edgar Buchanan's role as a powerless public defender inadvertently creates one of those emotional jumps from one movie to another: his earnest defense of what's right in this film makes his appearance 20 years later as a gin-soaked disgrace of a judge in Sam Peckinpah's Ride the High Country all the more poignant. Finally, poor Tom Tyler adds another hard-luck role to his career as a craven villain. Tyler was the gunfighter who goes up against a black cat and John Wayne at the end of Stagecoach. Stevens and John Ford were good buddies; I wonder if they chuckled at the thought of using Tyler only for thankless baddie roles. A year later, Tyler was in mummy makeup over at Universal filling in for Lon Chaney Jr., surely not a good sign for his ever getting recognition as an actor. The wonderful Rex Ingram is on hand as Colman's valet. He's not used for a single laugh, which is very progressive for a 1942 picture. He is given a giant closeup, shedding a tear for Colman's Lost Goatee, that racially sensitive viewers will find a bit much. All in all, when the movie is dated, it's very responsibly dated. 1 George Stevens is a formalist, and even though The Talk of the Town is an odd blend of civics lesson and screwball comedy, he gets in his cinematic licks. He can't resist symbolism, even if his use is more subtle than most. In the first big confrontation between rigid Rightness and desperate Railroaded, Cary Grant and Ronald Colman square off in a composition split by the bold diagonal of a stair banister that slices across the frame. Yep, this is an un-reconcilable difference, all right, the kind that will take creative cooperation by good Americans to solve. The best thing about Talk of the Town is how it avoids the political pitfalls of the demagogue Frank Capra. Capra's heroes tend toward a noble simplicity and innate Rightness that eventually bordered on fascistic God-hood. When Gary Cooper or James Stewart are beset by troubles, the whole world seems to want to crush them, until Capra's fantasy of 'the little people' (cute characters content to have no brains and stay anonymously adorable) come to their rescue, usually in the form of a benign mob. The mob, of course, always looks to the Hero for all leadership and values. Stevens may be a caviar liberal, but he knows that America isn't perfect and is willing to make a picture that says so, at a time when the national tone was to rally 'round the flag. The Talk of the Town is plenty corny in its own way, but it isn't Capra-Corn. We aren't encouraged to demonize the villains, as they aren't outrageous despots played by Edward Arnold, but rather fairly mundane figures: a manicurist, a foreman and a small-town Big Shot. At the end, we aren't primed to go storm Congress for Mr. Smith, or lynch a robber baron for John Doe. This is a very curious film for Cary Grant, who clearly would have given Stevens his left leg on a plate after the career boost of films like Gunga Din. The name 'Leopold Dilg' conjures an amalgam of 'dirty immigrant' criminal types, Presidential assassins, Lindbergh Baby-killers. The character is meant to be a political rabble-rouser, an agitator, perhaps even a Red, and his foreign-sounding name makes him even more suspect. In the 30s, these types were either scapegoats or comedy relief. That Stevens would champion such a character, and get Grant to play him, is pretty amazing. Of course, the last scene sees Dilg transformed back into smiling, tailored Cary. Star power dictates who gets the girl, and we wonder where Dilg is in such a hurry to go - to law school perhaps, or to join the ACLU? Columbia's DVD of The Talk of the Town breaks their streak of disappointing classic transfers. It looks great, with hardly a scratch in sight and a clear soundtrack. It was a pleasure to watch. The feature has no extras, just some trailers for other romantic comedies. Columbia isn't big on fancy content for its library titles, which in this case is a possible blessing, as it spares us an appearance by George Stevens Jr., whose reverential Pops-can-do-no-wrong interference (make that influence) tends to spoil DVD extras for his father's bigger studio pictures.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

The Talk of the Town rates:

Footnote:

1. Lost Goatee was

not the title of an earlier Colman/Capra movie about a disillusioned white man finding the Truth

among savages in a fantastic mountain paradise, among camel-like high altitude Llamas.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |