| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

M - Criterion Collection

NOTE: To see the screen captures of the new Criterion DVD of M compared with the 1998 DVD release, click here.

There are a handful of examples from film's first half-century that transcend any of the usual individual pursuits of filmmakers (entertainment, innovation, statement) to combine all that a film can be in one magnificent package. While working in the pre-World War II German film industry during the exciting years of expressionist productivity, Fritz Lang made two such films. His 1927 silent masterpiece Metropolis got the deluxe treatment from Kino last year and M, his first foray into sound film gets its second release from Criterion this year. This two-disc landmark release features a newly restored, mind-bendingly beautiful transfer and more in-depth extra features than most entire collections. For those who still wonder where Criterion got its reputation, this is the release to answer that question once and for all.

It's fitting that so much attention would be lavished on M. A touchstone for numerous generations of subsequent filmmakers, it boldly mixes style and substance to define how a film can tackle social issues and human stories in ways that make it unique from other artforms. Using all the tools at his disposal (camera tricks, angles, lighting, editing...) Lang builds a chilling atmosphere and plays with mysterious pacing to create a truly unique film.

Taking inspiration from a series of grisly murders in Germany at the time, Lang and then-wife and script writer Thea von Harbou fashioned a torn-from-the-headlines story that must have seemed urgent and topical but that is constructed like a Grimm fairy tale with allegorical qualities that can serve as a parable for many parts of the human psyche. The film's approach to characterization is bold and strange, with Lang's film techniques serving to tell the story of a mood and atmosphere as much as of a specific situation.

M tells the story of a child murderer (and, by suggestion, pedophile) who haunts the streets of Berlin. Hans Beckert (played by Peter Lorre) lures young girls with promises of candy and balloons but once off-screen he takes their lives in horribly violent ways. Lang doesn't show the murders but indicates them with spare, lonely images of empty streets and grieving mothers.

The film is also the story of the response of the public to the crimes: Mothers are horrified, the police are mobilized to carpet the streets, and the criminal underground is forced to form a vigilante mob in hopes of reclaiming their stalking grounds from the overbearing police presence. Lang explores all these angles in a hyper-realistic style that takes real-life and exaggerates it. Faces are ugly and contorted, characters walk hunched over and tense.

The entire populace seems on edge. Their anger over the crimes being committed allows them to expand their own outrage and direct it. Innocent people are stopped on the street for chatting with children. Lang explores the mob mentality, as when an elderly man stops to give a young girl the time. One bruiser of a man sees this and confronts the mousy businessman. "He's the murderer!" cries another passerby as an empty street quickly turns into a roiling mob. Lang uses camera angles and casting to emphasize the disconnect between a paranoid public.

The film's bold structure doesn't conform to our general sense of how a film is made: There isn't necessarily a central set of characters, other than the murderer and Inspector Karl Lohmann (Otto Wernicke). The name said most often is probably Elsie Beckmann, the little girl killed in the tense opening minutes. Instead, it's a film constructed like a mob: Countless nameless characters, often passing fleetingly before the audience, who create a great character of public panic. This strange structure might be off-putting to some viewers but it's Lang's deviation from the norm here that makes this nearly surreal procedural stand-out.

It's not quite the multi-character style of Robert Altman, but rather something else, something probably unfamiliar to modern audiences. I'm not sure if this storytelling style is something Lang thought could become a standard or if he thought it would work best for this particular film. But it does make for a strange viewing experience, especially when compared with modern cookie-cutter police procedurals. When the mob finally gets to put the murderer on trial in an impromptu kangaroo court it feels like the whole of German society - or humanity - is speaking as one.

But for the public to be one mass character there needs to be one other character: The murderer. And in this case there's never any mystery as to the identity of the man. Although he's only seen in shadow at first, Beckert is always the killer. The journey isn't in anything as mundane as discovering his identity but in exploring his mind set and the mind set of those hunting him.

As played by Peter Lorre, Hans Beckert is easily one of the most memorable film characters ever created. His sniveling, confused, angry, scared psychopath is over-the-top but passionately real. He's a self-hating criminal who both desperately wants to get caught and yet still tries to claw his way out of accepting responsibility like an animal. Beckert wants to stop killing (he knows it's wrong) but he feels compelled to the point that his murderous urges are like another person, following him everywhere he goes, demanding that he listen. This is an extraordinarily complex portrayal of the diseased criminal mind.

Lorre twists his face in extreme ways, utilizing the tools of melodramatic theater and silent film to become almost something other than human. But then with his pudgy body and sad features, he also becomes an everyman, a shuffling misfit who could wander through any crowd. If Hans Beckert and Travis Bickle passed each other on the street barely anyone would notice.

Lorre, who later perfected the sneering character performance in Hollywood masterpieces like Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon, delivers his most fiery, emotional, twisted, passionate performance here. He's riveting to watch and really leaves you with an unforgettable impression afterwards.

Between Lang's visuals and Lorre's character work, M is already a masterpiece. But among Lang's many other innovations is his bold use of sound. Being that it was Lang's first sound film, he didn't just tack dialog onto his usual style. Instead, he uses sound in a very stylized, experimental way. Often dialog from one scene and the next blend together in a shockingly modern style: Criminals and police officers with similar goals (catching the murderer) might finish each other's sentences thanks to well-timed cuts and sound design. This ramps up the film's pacing but also uses sound not just to convey information but to make a point.

Similarly, Lang uses the absence of sound very tellingly. Often he'll leave out the street sounds entirely, leaving the film floating in a creepy silence. He uses this technique to amplify the atmosphere and to force the viewer to remain engaged throughout. It also gives him the opportunity to get into the heads of his characters, who may want to block out distractions or who might be shocked by a sudden loud noise. He tries to put the audience inside the heads of his characters with these simple, effective techniques.

Lang's curiosity and experimentation lend M a sense of invention. Even something as simple as the voice of a mother calling her missing child's name repeatedly over desolate, lonely shots of empty streets and other urban views is powerful and provocative, especially considering that Lang created this scene so early in the sound film era. That attitude pervades every aspect of this ground-breaking film. That it's still so gripping over 70 years since its initial release really means something. M is as fresh today in many respects as it was in its day.

VIDEO:

This carefully restored transfer is absolutely a marvel. The black-and-white image is often razor sharp, with a minimum of unnatural enhancement. The grain is natural and the contrast is perfect. It's stunning that a film of this age can look so good. Modern audiences might take for granted the improvements here, but the difference between this release and any I've seen before is unreal. By taking the task of bringing M back to its release quality (and perhaps beyond) Criterion has really done a great service not just to film fans, but to world culture.

Even without watching the fascinating extra feature on the restoration it's clear that countless instances of damage and dirt have been removed: A film just doesn't reach this age looking as clean as this one does. There are some shots here and there where some dirt still exists and some shots are still imperfect, but the film looks spectacular.

It's presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.19:1, which is actually not as wide as a standard television set. (This strange aspect ratio was created to allow space for an optical soundtrack alongside the image.) Faced with the opposite problem of modern films (which are wider than a TV), Criterion have "pillarboxed" the image by including black bars on the sides. But they've actually gone one step further, slightly windowboxing the image on all sides to account for overscan, allowing more of the image to make it to the screen. Looking at their previous 1998 release of M (which featured a blurry image, a good deal of damage, cropping, and a frequent white line across the top of the screen) it's clear how far things have improved.

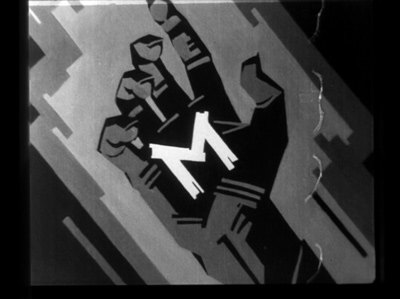

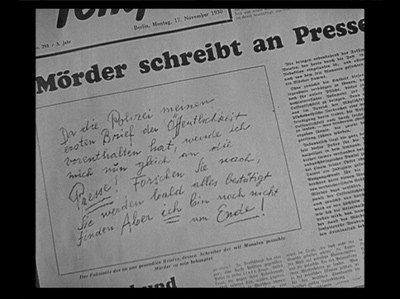

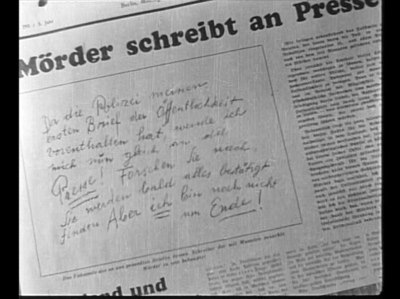

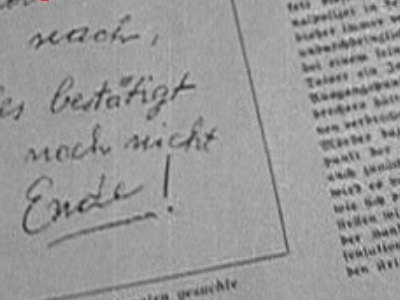

The following is a series of screen captures from the new Criterion edition of M, each followed by a similar capture from the 1998 Criterion disc. The difference is pretty pronounced. In some cases I've also included enlarged details. I haven't done anything to the captures except compress them as JPEGs at a pretty high quality level (about 80%). They should give a good idea of the improvements:

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

Enlarged detail from 2004 transfer

Enlarged detail from 1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

Enlarged detail from 2004 transfer

Enlarged detail from 1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

Enlarged detail from 2004 transfer

Enlarged detail from 1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

Enlarged detail from 2004 transfer

Enlarged detail from 1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

2004 transfer

1998 transfer

Note: There is some slight cropping on the sides in the new version when compared to a European release of M by Eureka, but that version exhibits much more added sharpening and features a less enjoyable image overall.

AUDIO:

The Dolby Digital Mono soundtrack is amazing for its age and origins. There is real clarity to the voices that makes them totally distinct. Obviously this is not a modern audio mix by any means but it's exceptionally done. Lang's use of sound, as I've mentioned, was extremely bold and innovative and the treatment of his work here is superb. I've reviewed DVDs of recent films with less audio clarity than this. The film is in German with optional English subtitles (from a new translation).

EXTRAS:

The extras in this set are absolutely perfect all the way. They approach the material with the intention of giving the viewer a real sense of context and they deliver. Accompanying the film is a very interesting commentary track by German film scholar Eric Rentschler, author of The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife, and Anton Kaes, author of the BFI Film Classics volume on M. This conversational commentary is filled with interesting insight not only into the specifics of the film and how it was made but on its place in German film history and culture. The participants are extremely knowledgeable on Lang's career and discuss at length the themes he brought to M and the state of Germany when he made it. They also at times seem to even surprise each other with particular insights and tidbits. There are some lags in the discussion and they might be a little dry for some but this is an excellent track.

The second disc holds a treasure trove of unique and interesting features. First up is William Friedkin's 50 minute interview with Fritz Lang, filmed in 1974. This lengthy sequence features Lang speaking in great depth about his life, his approach to film and how the world changed around him. Looking particularly striking in his old age with his eye-patch, Lang cuts a very strange figure. His thick accent and cranky tone reminded me of Dr. Strangelove. But his storytelling is slow and engaging. He unravels tales from his life with the style of a man with a lot to say. An outstanding extra feature.

A unique feature included is Claude Chabrol's M: le Maudit, a short film based on M that was part of a strange French television series that offered up Cliff's Notes-style distillations of classic films. Chabrol's version uses some footage from M and some original footage shot with a French cast. This unusual feature gives the viewer another chance to appreciate the influence the film had on future filmmakers.

One of the best features is the "Physical History of M" which shows some of the changes that were made to the film over the years. It's really fascinating to see some of the alterations made for the French release, including re-shot footage of Lorre reading his lines in French. Also, street scenes are included where footsteps and car noise replaced the eery silence of Lang's original. Thankfully these alterations exist only in this historical piece. There are also clips from other sources, like a piece of Nazi propaganda that incoherently tries to make the case that Jews are debased sub-humans by showcasing different kinds of art and film, including a clip from Lorre's final monolog. Really an excellent addition to this feature. Finally, the segment compares the newly restored version to previous prints. If my screen captures aren't enough to convince you of the worth of this restoration, this terrific sequence should.

There is also an interview with Harold Nebenzal, the son of the film's producer. He spends a good bit of time discussing his father's career and how he came to produce the film. He also talks about his father's exodus from Germany once the Nazi era got underway and his work in Hollywood, where he produced a well-received remake of M that fell prey to the Communist blacklist thanks to the leanings of the remake's director. That version is not readily available today. Pity since it would have been the ultimate special feature on this set.

There is also a series of audio-only lectures given by M editor Paul Falkenberg at the New School. He discusses the film while it plays (the disc uses the new transfer although the lectures are from the 70s) and answers questions from students, stopping the film along the way to point things out. This outstanding feature really gets into Lang's style of working as well as how editing helped shape the film.

The disc also includes a stills gallery featuring rare behind-the-scenes photos, and production sketches by art director Emil Hasler.

If all this wasn't enough, Criterion extends the outstanding treatment of the film to the accompanying booklet. Writings include an essay by critic Stanley Kauffman, the script for a missing scene that may have actually been shot but removed by the censor board, an interview with Lang on the film from 1963, an essay the filmmaker wrote for a German newspaper before the film was released, a negative review of the film from the original release, and a letter to a German newspaper from an unnamed member of the criminal underground supporting the film's view of street life. Simply required reading for fans of the film.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

M is a landmark piece of art that transcends film entirely. It has had an influence over filmmaking that cannot be measured. Filmmakers like David Fincher, Steven Spielberg, Brian DePalma and many, many more have absorbed Lang's techniques and ideas and used them to inform their own stylized works. While not a political film, per se, it also achieves a certain psycho-social depth that is remarkable for its age and time period. Lang's place in film history as a master of both form and substance is secure thanks to M as well as other great films like Metropolis and Fury and having more of his legacy in such excellent shape can only help future generations appreciate that.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||