| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Canterbury Tale - Criterion Collection, A

THE MOVIE:

For their 1944 feature, A Canterbury Tale, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (a.k.a. the Archers) tipped their hats to Chaucer's classic collection of stories, The Canterbury Tales. A movie about balancing old and new values in the face of modern advances and the haze of difficulty, it picks up Chaucer's device of religious pilgrims traveling to the British countryside and applies it to WWII England. A classic feel-good movie, A Canterbury Tale has finally come to DVD courtesy of the fine folks at the Criterion Collection.

Three travelers get off of a train at a small English outpost: a British soldier on the way to his regimen, an American GI who jumped off a stop early by mistake, and a member of the Women's Land Army (a.k.a. a "landgirl") assigned to the area, filling an agricultural void left by men who have gone off to fight. They find themselves in Chillingbourne, a village in the Kent region, in the dead of night. On their way to the Town Hall to get situated, they are attacked by the Glue Man, a bizarre criminal who dumps glue into women's hair. The landgirl, Alison (Sheila Sim), ends up being his latest victim, and the trio unites to solve the mystery. Their exploits are like a charming precursor to Scooby-Doo, including a solution that involves an old man in a costume.

Their sleuthing ends up having a greater effect on them than just solving the crime, however. All three begin to learn more about the history of the countryside. The town they have stopped in is the last bend on the Pilgrims' Road, the legendary path to Canterbury. The ultimate goal of any pilgrimage is to get to Canterbury Cathedral, where blessings are to be had. Their journey ends up being orchestrated under the tutelage of the slightly odd town magistrate, a cold fish named Thomas Colpeper (Eric Portman). Colpeper is more than he seems, almost acting like a divine hand to nudge his charges onto the proper path. Once they do arrive in Canterbury in the final reel, all of them rediscover something they thought they had lost. Given how beautiful A Canterbury Tale's cinematography is, it's hard not to feel just as blessed as our hapless pilgrims. Shot by Erwin Hillier, he and the Archers capture remarkable footage of the cathedral, both inside and out. Its enormity and detail is staggering.

There are multiple reminders throughout the narrative that the world has gone topsy turvy due to the war. The older citizens in particular have a good eye for life being off kilter, as WWII isn't the first conflict they've lived through. Colpeper wants to preserve the history of the region he grew up in, and as a result, he is kind of a stand-in for Michael Powell, who himself is using A Canterbury Tale to share his birthplace with the ages. Each of the pilgrims has lost their way on their journey to Kent. Alison has sacrificed a fiancé to battle, and she has returned to Chillingbourne to work the land in an attempt to reconnect with him. He was a geologist before the war (everyone was something else before the war), and his excavation of Pilgrims' Road has brought her back to the site of their best time together. The American, Sgt. Bob Johnson (played by a real U.S. Army Sergeant, John Sweet), is a likable guy who feels disconnected from the life he left behind, as well as the girl whose letters have stopped arriving in the mail. Finally, Sgt. Peter Gibbs (Dennis Price) was an organ player who decided to play in a movie theatre rather than a church, a move indicative of his loss of faith in any sort of greater good. It's one of several sly jokes about motion pictures. Johnson is also a film fan, one who refuses to settle for a single feature matinee or any kind of free show. The danger of movies, Colpeper warns, is that its audience is merely sitting still, watching life happen instead of participating in it.

And essentially, that's the fate the characters of A Canterbury Tale are saved from: a life of complacency. They all three will find new connections to all of the things they have let slip. It's a genuinely heartwarming climax, something the Archers were supremely skilled at. No one can match the duo for creating rarefied worlds filled with charming personalities who remind you that life is worth living. Somehow they manage to do it without ever making their audience feel they are being hammered with a message; nor do they sugarcoat everything to the point of rotting your teeth. The denizens of their small town don't ever feel forced, belittled, or contrived the way filmmakers so often do when trying to portray anyplace that's not a big city. Powell & Pressburger have too much of an affinity for human nature, enjoying the quirks that make us unique. My favorite scene in A Canterbury Tale is when Johnson joins a play-army of children for their pretend war. As they hurl fruit and rocks and whatever they can lay their hands on at one another, a small child in a naval commander's uniform stands in a rowboat on the river and cries over the loss of his vessel. Less adept directors would have overplayed it, but the Archers just let it stand, knowing it's delightful enough without adornment or comment.

The fact that we are treated to some fantastic filmmaking on the way to this miraculous conclusion is just an added bonus. As I already noted, the footage of Canterbury Cathedral is breathtaking, but the shots of the fields of Kent are also gorgeous. In a scene where the four characters are standing in the tall grasses at the top of a hill, we see the whole of the town, and when Johnson notes how beautiful it all is, Hillier's camera backs him up by filling the whole frame with the green landscape. Juxtaposed against this splendor is devastating footage of the bombed-out sections of Canterbury. As the cathedral looms tall over the town, these pits of destruction end up being its opposite. Alison walks the edge of the phantom buildings, marked now by signs informing passersby of where the businesses have since relocated. They stand as potent symbols of both the consequences of war and man's resiliency in the face of it.

Having captured the landscape of Canterbury at the time that they did, the Archers serve their own purpose of preserving values that may be lost, taking a snapshot of a moment in time where a population is at a crossroads and risks going the wrong way. Everything in the movie points towards reminding its characters not to rush too fast towards uncertainty when history has already solidified a foundation of knowledge that could ease some of the guesswork about the future. Even the seemingly silly Glue Man ends up in service to this theme when his full motives are revealed. His glue dumping is his attempt to stop young women in their tracks, to prevent them from letting themselves be corrupted (or, as it were, maybe stopping them from distracting the soldiers). Naturally, this is a rather extreme tactic, but it's also part of the balance that the Archers give the story. Not all of modernity is bad. Sgt. Johnson is probably the most obvious example of shifting values, representing as he does the American cultural invasion, but he's carefully given a firm background in a very traditional subject: wood. Similarly, even Alison and Colpeper come to an understanding during a tender hilltop confessional where Alison reveals the personal tragedy that caused her to so dramatically change her life from shopgirl to patriotic farmgirl.

When you stop to think about it, the lesson the Archers give to their characters is also the one they give to their audience. When Alison and Johnson and Gibbs once more believe that miracles can happen, so do we--even if it's just a belief in cinematic ones. (So, take that, Colpeper!) That's the wonder of A Canterbury Tale, and the blessing Powell & Pressburger bestow on all who make the pilgrimage to the theatre--or, in this case, wherever you get your DVDs.

THE DVD

Video:

Criterion has used a newly restored digital transfer of A Canterbury Tale, shown in full screen at a 1.33:1 aspect ratio. It's a good print, though not perfect. There are frequent lines on the screen and occasional hazy phantoms. The contrasts, however, are always good, and given the that more scenes are crisp and completely clear than otherwise, it's likely the best use of the materials available at the moment and thus, easy to forgive.

Sound:

A monaural mix without much hiss. The dialogue is clear, the music is loud.

Extras:

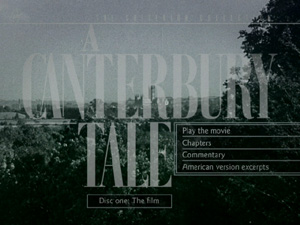

A ton. There are two discs here, the second one devoted entirely to bonus features.

On the main disc, in addition to the movie, there is a feature length commentary by film historian Ian Christie and two scenes from an American version of A Canterbury Tale featuring John Sweet and Kim Hunter. It's surprising to hear that A Canterbury Tale wasn't successful when it first came out; in fact, a lot of the extras speak about what a "strange" film it is. Maybe given the hindsight we now have to look at the full breadth of the Archers filmography, it's easier to see that all of their films had a bit of strangeness, but apparently A Canterbury Tale baffled the original audience and critics. Powell re-edited the film for the American market, reordering scenes and significantly cutting the length. He also shot a prologue and epilogue where Sgt. Johnson convinces his new wife (Hunter) to visit Canterbury for their honeymoon. They're rather clumsy curiosities, lacking the usual grace of a Pressburger script. (It's surprising Criterion didn't include both versions the way they have with Visconti's The Leopard and De Sica's Terminal Station, especially since the re-edit apparently was the version run on television until the late '70s.)

Christie's commentary is an involving blend of historical facts (both about Chaucer's Canterbury and WWII), anecdotes from the set, and film theory. He offers a lot of insightful information on how the film was put together and the forces of the outside world that may have influenced the choices made. He also places A Canterbury Tale within the larger context of film history, including the influence of German filmmakers of the '20s and '30s, the film noir that was being made in America concurrently with this production, and the future of the Archers and similar films by the likes of Roberto Rossellini. Perhaps the most shocking revelation is that, outside of one shot of the ceiling of Canterbury Cathedral, the film crew was not allowed inside the building. All interior shots were recreated in a studio!

Disc 2 is the Supplements. Leading the way is a contemporary interview with actress Sheila Sim. A Canterbury Tale was her first movie, and she takes us through the casting, mishaps on the set due to her naïveté, and the patriotic nature of the film along with the ongoing questions of British identity. It's a nice discussion, tinged with genuine nostalgia.

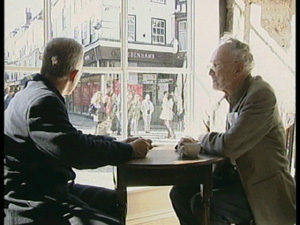

The 2001 documentary A Pilgrim's Return catches up with John Sweet in Canterbury in conjunction with a Powell-Pressburger retrospective the former actor was attending. It's more effective as a time capsule than the interview with Sim, in that Sweet has a real emotional reaction to seeing both the city and the film after so long a time. Age and experience have allowed him to understand depths of the movie he didn't comprehend when making it. He discusses what happened to him after the war, tackles the image of Powell as a harsh taskmaster by comparing him favorably to a commanding officer in the armed forces, and reveals some parallels between his real life and the fictional soldier he portrayed.

The nostalgic feeling continues in the short 2005 piece, A Canterbury Trail. A chronicle of an annual walking tour through the various settings of the movie, this particular year was the centenary of Michael Powell's birth, so the tour was expanded to include sites from his childhood. While it's interesting to see how some of the areas have been preserved--and some not--the feature does drag a little. It's kind of like being stuck on the tour even though you wanted to go home some time before.

The final extra is a collection of pieces under the title Listen to Britain. In an essay that precedes both video segments, artist Victor Burgin explains that just after 9/11, he was commissioned to do a museum installation about the state of England. On a cross-country train ride, his memory took him back to A Canterbury Tale and a 1942 documentary by Humphrey Jennings. The Jennings film is presented here, a short documentary called Listen to Britain that shows various activities around the country during wartime England, presented as a montage with no narration. Burgin used a similar style for his Listen to Britain, using pieces of film from A Canterbury Tale and new shots of the same scenery to create a filmic painting intended to inspire viewers to think of the previous time England's stability was under threat. It's somewhat insubstantial, but as Burgin explains, it was intended to be viewed by people walking in and out of the room, not sat and watched in its entirety. In the spirit of its original function, it's been put on the DVD as a loop, as well, so be careful. If you aren't paying attention, Listen to Britain will start over and you might be a couple of minutes in before you realize!

So, the meat of the extras is on disc 1. If you want to gain a more in-depth knowledge of this Powell & Pressburger gem, Ian Christie's commentary is the place to go. If you want to know more about the lasting impact the movie had on fans and crew alike, then spend some time with disc 2.

As with all Criterion discs, A Canterbury Tale comes with a handsome booklet of photographs, credits, and essays. In this case, you get two critical pieces by Graham Fuller and Peter von Bagh, and an extensive write-up by John Sweet about how he got the role of Bob Johnson and what it took for an amateur to survive his first movie.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

Highly Recommended. A Canterbury Tale is an enchanting cinematic parable that inspires and uplifts, reminding contemporary audiences of the struggles of the past and how they may reflect on the present and future. It's also a vindication of cinema as a potent artistic force, with one of the medium's finest team of craftsmen working at the height of their powers. Given the healthy dose of extras that come with it, the 2-disc Criterion of A Canterbury Tale is not to be missed. I'd wager it'll become one of those films you loan out time and again, enlisting new pilgrims in the Powell & Pressburger caravan.

Jamie S. Rich is a novelist and comic book writer. He is best known for his collaborations with Joelle Jones, including the hardboiled crime comic book You Have Killed Me, the challenging romance 12 Reasons Why I Love Her, and the 2007 prose novel Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?, for which Jones did the cover. All three were published by Oni Press. His most recent projects include the futuristic romance A Boy and a Girl with Natalie Nourigat; Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks, a loopy crime tale drawn by Dan Christensen; and the horror miniseries Madame Frankenstein, a collaboration with Megan Levens. Follow Rich's blog at Confessions123.com.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||