| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Emperor of the North (a.k.a Emperor of the North Pole)

If you were a movie-crazy kid who practically lived at the theaters during the Seventies, you remember that there was one overriding factor that determined what you were going to see on a given Saturday afternoon: the film's rating. If your Mom got the right answer from the ticket taker - which of course could only be "G," "GP," or later "PG" - then, and only then, were you given your candy money and shooed on your way. Otherwise, wish away in front of the "R" rated posters, kid, 'cause you're not going in. So imagine my wonderment in 1973 when, two hours after being dropped off with my older brother at the local movie house, I gleefully informed my Mom that she had just paid for me to see any number of gory mayhems, including iron sledgehammers to the head, vivisection by train, and a full-on axe blow to the arm, bright with red paint/blood, all courtesy of director Robert Aldrich's PG-rated, action/allegory train epic, Emperor of the North, starring Lee Marvin and Ernest Borgnine. Mom almost had the vapors, but Dad, after hearing my dizzying review, took me back again later that week, bless him. On the Q.T., of course.

Unfortunately, not enough Moms mistakenly let their boys see this film. Robert Aldrich, hoping to recapture the glory that was his earlier, all male action hit, 1967's top-grosser, The Dirty Dozen, fashioned a sure-fire audience pleaser that somehow managed to find no audience, but which had most critics giving praise to his myth-making efforts. It was violent, it was funny (well, not top-notch Aldrich funny, like next year's The Longest Yard), and it moved, if you'll pardon me, like an express train (until a faltering third act). Clearly, Aldrich and screenwriter Christopher Knopf (the story was based, very loosely, on the books The Road by Jack London and From Coast to Coast with Jack London by "A-No.-1" (pen-name of Leon Ray Livingston) were reaching for more than just an actioner to please the yobs in the stalls; gore and violence are a means to an end in Aldrich's artistic vision (as anyone who has seen the classic Kiss Me Deadly and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? knows). But did he succeed here in delivering more than just a first-rate actioner? To listen to the Aldrich cultists, he did. To listen to those movie fans who champion any "lost" or "forgotten" film all out of proportion to its merits, he did. But to me? Hmm..................

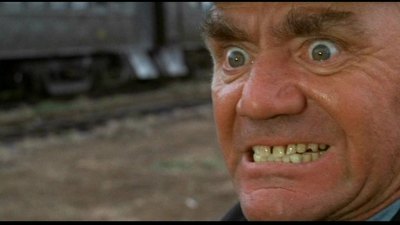

It's a deceptively simple story that doesn't bear too much re-telling. It's 1933, as the title card reads, at the height of the Great Depression. Men must be tough to survive, tougher than the machines that serve them. Shack (Ernest Borgnine), a vicious, sadistic railway man, allows no one to ride his train without a ticket. No one. And those that dare to, those hobos that ride the rails in search of...in search of anything to survive, who break the rules of Shack's world by mooching a ride, give up all rights as individuals, and thus can be killed with impunity. You jump Shack's train, and you stand a good chance of going under the wheels at his hands, just as the first 'bo does in the film's horrific opening sequence (Thanks, Mom!). For that matter, even if you work alongside Shack, if you're a social equal to Shack, you could get a good throttling for your efforts. He's a voracious black hole of hatred and violence; it's tough to tell if the sounds of hissing steam, clanking metal, and screeching wheels are coming from the train, or from Shack's boiling, rage-filled head and body.

But if you're A-#1 (Lee Marvin), you're King of the Hobos, the Emperor of the North Pole, and you ride whatever rail you want (The stars at night -- I put 'em there. And I know the Presidents -- all of 'em -- and I go where I damn well please.). You stride confidently through Depression-era America; you've seen it all and done it twice. Whatever story you tell is true because you're telling it, regardless of the facts, and you can make anybody believe it because not only are you tough enough to back it up, but a sense of royalty, an unerring sense of class, surrounds you. You're a natural born leader who's looked up to by the other stewbums. And nobody, including the dreaded Shack, is going to stop you from hitching a ride to Portland on the Number 19 train.

The character triangle is complete when the young braggart punk Cigaret (Keith Carradine) is introduced. Cigaret wants to be the new top 'bo, but his dismal, confrontational, grating boasting clearly undercuts whatever skills he may have. As A-#1 says later to him, he's got the juice, but not the heart. If he is to survive, he must learn from A-#1. But can you learn that elusive quality of "class"? Exactly why A-#1 chooses to help him, ultimately, is anyone's guess. But they team up (sort of) against Shack to ride his train, to create a new story for the bums and 'bos that live in the hobo jungles along the tracks, to give hope to them that evil incarnate Shack - the very embodiment of the crushing economic and social depression that has gutted these men/animals - cannot snuff out their dreams. The story will become the myth, as will the man, A-#1.

Two main plot points are thus repeated throughout the remainder of the film: A-#1 and Cigaret go back and forth about what it takes to be a bum/man, and A-#1 and Cigaret alternately board, and get thrown off, Shack's train. Repeatedly. These repetitions aren't tiresome (that's impossible with the energy and vitality that Aldrich puts up on the screen), but it would only spoil it for the viewer to recount them here in detail. Of course, these cat-and-mouse games lead up to the film's climax, an all-out, ultimate battle between Shack and A-#1 on a flat car.

There's no question that Aldrich is clearly in his element when the action scenes take over (which make up the majority of the film). The brutality and full-force violence of his vision is believable, and almost gleeful, in its presentation to the audience. Several of the set pieces are remarkable for their drive and editing (courtesy of editor Michael Luciano, with assistance from Roland Gross and Frank Capacchione). The scene involving the near collision of Number 19 with a fast-moving mail train - a predicament caused by A-#1, by the way, who callously ignores the impending results of this collision - is beautifully done. The scenery is magnificent, aided by Aldrich trucking his camera over some of the same railway lines that provided Buster Keaton with locations for his masterpiece, The General (around the town of Cottage Grove, Oregon, along the right-of-way of the real-life Oregon, Pacific and Eastern Railway). The various fights aboard the train are spectacular, with many shots showing the lead actors actually doing their own stunts. And the celebrated fight scene at the end, complete with near-perfect action compositions (and some shakily matched exterior lighting -- each new shot may be cloudy or sunny), simultaneously thrilled and shocked the few people who saw it on the big screen.

The performances are uniformly fine, as well, with a particular standout being Borgnine's demonic Shack. Borgnine exhibits an almost preternatural affinity here for the primitive Id, supercharged and abetted by various crude implements of violence, including sledgehammers, chains, and a particularly deadly lynchpin, dangled by a rope under the railroad cars, allowing it to bounce up off the railroad ties and beat senseless the 'bos that perch there. His close-ups are startling in their menace and intensity; they rival some of Sergio Leone's celebrated head shots. Marvin, who looks disturbingly older and paunchier than his appearance only a year earlier, in Prime Cut, certainly looks weather-worn and rough-and-tumble. No one could toss off a throw-away glance like Marvin, expressing comic low-level disdain, or incomprehension. He's quite funny, as always. And physically, he's spot on; he looks like a powerful, yet ragged, jungle cat: quick-witted, sinewy, innately graceful. As Cigaret, Keith Carradine is annoyingly perfect. Have you ever thoroughly wanted to watch someone get thrown from a train? No? Well, watch Carradine and cringe. Other stalwart character actors such as Charles Tyner, Malcolm Atterbury, Hal Baylor, Matt Clark, Liam Dunn, Robert Foulk and Vic Tayback lend their usual solid support.

Some of the language of the screenplay has a ramshackle poetry to it that captures the otherworldly, mythical tone Aldrich set out to achieve. Several of the lyrical speeches in the film, where A-#1 poetically expounds on his credo, work well, particularly Marvin's thrilling final speech (Stick to barns, kid! Run like the devil! Get a tin can and take up moochin'! Tackle back doors for a nickel! Tell 'em your story! Make 'em weep! You could've been a meat eater, kid! But you didn't listen to me when I laid it down! Stay off the tracks! Forget it! It's a bum's world for a bum!).

However, Aldrich runs into trouble when the drama's mechanics are looked at too closely. Just from a time standpoint, the film is too long to support the story, the main culprits being a trio of scenes at the beginning of the third act that criminally stop the movie dead in its tracks. Just when A-#1 and Cigaret (after getting kicked off Shack's train...again) have caught up with the Number 19 and Shack, just when the movie should go straight into maximum overdrive, Aldrich throws in three scenes that quite frankly, are an embarrassment. First, Marvin steals a turkey, and humiliates railyard cop Simon Oakland into barking like a dog (yep, it plays just as badly as it reads). Second, Marvin has a largely unmotivated confrontation scene with Carradine in a hobo shack that almost plays like it was lifted from an earlier section of the movie. From Carradine's bewildered reaction shots, and some of the dialogue which goes over thematic territory supposedly already settled between the two characters, we feel like we're mistakenly watching a reel from the first half hour of the film. And third, Aldrich throws in a gratuitous Baptism "comedy" scene that supposedly shows how Marvin teaches Carradine to steal clothes (which we never see), but which plays out as a cheap excuse to show a girl with wet, clinging clothes, and some heavy-handed mugging from Marvin, ogling her. These scenes really put the brakes on the film's momentum, and they show how crudely (and at times, such as here, how ineptly) Aldrich handled his comedy scenes.

The film, released in late May of 1973, failed to find even an audience of undiscriminating action fans. Although it's always guesswork as to why any particular film either does or doesn't tickle an audience's fancy, the unrelenting, gruesome violence may have been a turn-off to the women in the audience. As well, Marvin certainly wasn't in the top tier of box-office attractions anymore (Borgnine never had the kind of pull, as the generic saying went, "that put asses in the seats."). And there was speculation that the title (which was changed late in the game from "Emperor of the North Pole") may have thrown audiences, making them think they were seeing something about the wilds of the Arctic. Movie reviewers at the time were quite positive about the film, despite today's perception (including that of the critic on the commentary track) that the film was a flop with the critics (in fact, many critics compared it most favorably against the then-current release of Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid).

After the movie's failure with audiences (which Aldrich stated he couldn't quite understand), Aldrich gave an interview (a print interview, not included in the DVD) where he stated that the characters were created as archetypes, representing The Establishment (Borgnine), The Anti-Establishment (Marvin), and The Youth of Today (1973, that is) Who Won't Fight On Either Side (Carradine). Aldrich shows Cigaret failing to learn A-#1's lessons, numerous times, yet he can't fit into Shack's world, either. He is essentially, passive (as the final fight scene shows). Evidently, Aldrich had envisioned the film for young adults, as sort of a wake-up call to them, to shake off their sleepy acquiescence of society's ills. When told by the interviewer that the youth of 1973 didn't want to hear that about themselves, Aldrich merely stated, "I don't care." Well, that might explain why audiences didn't show up, but I suspect that isn't entirely why the movie flopped.

First and foremost, Aldrich fails in his above-stated intentions. If A-#1 was supposed to be Anti-Establishment, then why does Aldrich (and to be fair, screenwriter Christopher Knopf) make him the role model for all the other 'bos to look up to? He is the standard bearer; he is the ideal to which they all aspire. He reigns over his own society of castoffs, and his rules of conduct - both moral and societal - are as rigid as any other firmly established ruler. Of course, he rebels against Shack, but society has already cast him aside; he's hardly an agent for greater change.

Shack works perfectly well as a symbol of Evil incarnate; but as a symbol of The Establishment? If Borgnine stands for The Establishment (it has been said that Aldrich specifically stripped Shack's gradual descent into Hell from an earlier screenplay draft, making him instantly Evil from the start of the film), why then does he buck his own men, and the rules of the yard? Why does he throw aside all caution, dangerously "highballing" through the yard? Why does he push the old train past its endurance level, repeatedly against the wishes of his engineer? Wouldn't The Establishment respect these rules? Are not the rules King to the Establishment? Shack has his own set of rules, totally outside the established order; essentially, he's no different than A-#1. His sense of self is ruled by what he can and cannot allow - no one will ride his train. Period. And if The Establishment, and thus Shack, is inherently and totally evil, as Aldrich stated at the time, a theme that reoccurs in several of his other films, why then does Shack show vulnerability, indeed concern, for the impending collision between the two trains? Why does he ask A-#1, indirectly, for help, implying that A-#1 and the other 'bos should stop their games long enough for Shack to get the train out of the way, so that ten people won't needlessly die? It's A-#1 who callously responds to Shack here: "Sounds like a ghost story to me."

As for Cigaret, even the director couldn't adequately explain why A-#1 would help such a loathsome creature, after his numerous betrayals of A-#1. At one point in the film, when Cigaret asks A-#1 why he's bothering to teach him anything, Marvin replies, "I'm still working on that." Their relationship is only necessary to perpetuate the Teacher/Student dynamic in the mythology. As far as it relates to the reality of the drama, it makes no sense.

And ultimately, if we spend too much time with them, archetypes tend to become, frankly, boring and one-dimensional. Originally, the film was to be directed (somewhat incongruously) by Martin Ritt. He was fired, and the project was bumped to that master of violence-as-guilty-pleasure, Sam Peckinpah. But money stood between Peckinpah and the film, and the package was turned over to Aldrich. One can only wonder what Peckinpah would have done with the characters in this film. The violence certainly would have been intact, but far from simply presenting vague, mythical cardboard characters (enjoyable here, nonetheless, because of the performances), Peckinpah may have imbued the characters with gradations of motivation that would have deepened the allegory Aldrich envisioned. Then again, he might have blown the whole project like he did to so many of his other later films. Who knows. The point is, Aldrich clearly wants these archetypes to occupy a schematic for "Larger Things," when it may have sufficed to have them fleshed out, to stand for real characters. Of course, big, vague ideas are easy to throw around; it's harder to get the specifics right. Don't get me wrong; it's refreshing to see characters exist only in the physical -- I'll take a character with no history any day over badly written exposition. And as a visceral, physical film, it succeeds masterfully. No need to ask any more of the film than that. But when you're setting out to make "Myths" and "Legends," when you're asking much more of your standard (yet expertly handled) material than is normally given, you better, as A-#1 would have said, be a meat eater, kid.

The DVD:

Video:

20th Century Fox's DVD presentation of Emperor of the North is a real gift to fans who have only seen the film in washed out, pan-and-scan copies on TV. The anamorphic widescreen format restores the picture to its correct 1.85:1 ratio, with deep, rich colors, courtesy of master lenser Joseph Biroc. Some grain is apparent, but that's the way the film looked back then. Blacks are fairly black; any haze in the picture comes from the intended effects of the cinematography.

Audio:

The optional Dolby Digital stereo track is thin and undirected; speaking of which, get a load of Frank DeVol's and Hal David insipid, literal song A Man and A Train. Remember: A train's not a man, and a man's not a train, for a man can do things a train never can. These addle-pated bromides are courtesy of the man who gave lyrics to that camp classic Lost Horizon the same year. You're better off listening to the original mono track. Alternate Spanish and French mono audio tracks are included. Close captions in English and Spanish are optional.

Extras:

A theatrical trailer and two television spots are included; all three push the main fight scene as the film's selling point. A breathless, insistent commentary track is included by Cinema Studies Professor Dana Polan. It would make a great thesis paper, but almost all of the conclusions drawn are at best, debatable (the theme song is indicative of the 1970's Captain and Tennille sound?!?), with some observations just plain wrong (For instance, Polan's notion that the inclusion of actor Harry Caesar makes this a "liberal seventies film" because Aldrich doesn't have Shack give into the racism of the 1930s, by commenting on the fact that his coal scooper is black. Really? I guess that's why he never refers to Caesar's character by name, but instead by screaming at him, "you black bastard!" or simply referring to him as, "the black." So much for Shack's color blindness).

Final Thoughts:

Whatever Aldrich's stated intentions were for the film's message, he most clearly gets across the vitality, the vicarious physical thrill of sadistic violence on the audience. Emperor of the North is an exciting, grueling, exhilarating ode to Man, Myth, Humanity, Machines, Sadism and Violence. Those totems aren't meant to be condescending; indeed, the director clearly designed the film to be viewed this way. And for the most part, he succeeds in entertaining us immensely. That's why I highly recommend this DVD. But whether Aldrich enlightens us any further on those lofty subjects? Hmm...............

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||