| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

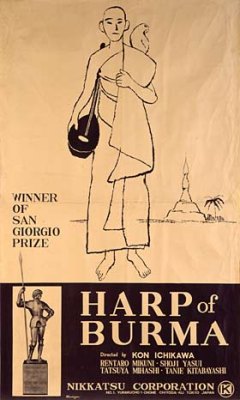

Burmese Harp - Criterion Collection, The

The international success of The Burmese Harp (released at the time as Harp of Burma) established an inaccurate portrait of its director. This and Fires on the Plain (Nobi, 1959) seemed to peg director Kon Ichikawa as a filmmaker specializing in antiwar dramas. In fact up to this time Ichikawa was best known in Japan for his biting contemporary satires, which remain among his very best pictures even though they're almost never shown in America and, up to now, haven't been released to home video in the west.

Based on the novel by Michio Takeyama and adapted for the screen by Ichikawa's wife, Natto Wada, The Burmese Harp follows a platoon starving and on the run in July 1945. Gentle Captain Inoue (Rentaro Mikuni), with a civilian background in music education, keeps his men's spirits up by teaching them choral music, with Private Mizushima (Shoji Yasui) accompanying them on a Burmese harp he's taught himself to play.

The war ends and Inoue and his men surrender, but Mizushima volunteers to try and convince another platoon, holed up in a remote cave in the mountains, to surrender to the British. However, the unit's commander (Tatsuya Mihashi) vehemently refuses to surrender: he and his men would rather die honorably than acquiesce. The cave is shelled and dozens die meaninglessly.

Making his way back to the relocation center/prison camp in Mudon, Mizushima gradually fades into the landscape, adopting the robes of a Buddhist monk and, en route, is overwhelmed by the endless piles of rotting Japanese corpses, shown in very honest and graphic terms by mid-1950s movie standards. "The soil of Burma is red," reads the text that opens and closes the film, "and so are the rocks."

The Burmese Harp has variously been described as an antiwar film, an adult fairy tale, a religious odyssey of enlightenment, a sentimental war drama, a kind of penance for the senseless loss of human life at the hands of Japan's militarists. In fact it's all these things, and Ichikawa and Wada for the most part manage to juggle all these balls in the air at once with nary a misstep. Seen today, the film is more impressive for its visual design and its unusualness - there's nothing quite like it in early postwar Japanese cinema - than its emotional impact, though like the men in Inoue's charge most Japanese audiences can't watch it without crying their eyes out.

As Ichikawa points out in the 2005 interview about the film, included as an extra feature, only a few scenes with actor Yasui were actually shot abroad; most of the film was made in Japan, near Hakone and Izu, though unless the viewer has actually been to Myanmar the effect is completely convincing. Ichikawa and longtime Shintoho/Nikkatsu cinematographer Minoru Yokoyama's compositions are vivid and evocative with painterly framing and lighting. The black and white photography, with its high-contrast compositions, creates a movie-real grittiness for the battle-type scenes that simultaneously allow for poetic, ethereal vignettes that at appropriate times convey a dream-like quality. The screenplay deftly splinters off into two directions, telling its story from two perspectives: the men wondering about Mizushima's fate, and Mizushima's odyssey, with a chance encounter on a bridge as the fulcrum in which these points of view intertwine.

That the film plays at times like filmed novel lends it both its uniqueness and a certain weakness. Some images, like the transformed Mizushima standing in a field in his newly adopted monk's robes with two parrots on his shoulders, as Inoue's fenced-in men watch him from a distance, are beautifully realized and work wonderfully well. But the film's barrage of sentimental songs (and composer Akira Ifukube's mournful underscoring, at times nearly identical to cues he wrote for 1954's Gojira) is extravagantly overdone, hammering away at its core message on the universality of music and its use, as write Tony Rayns describes it, as "salve for the soul." At times the film threatens to become insufferably noble while ignoring the realities of Japan's militarism in Asia, but the filmmaking is at such a high level it's easy to ignore this and lose oneself in its hypnotic telling.

Video & Audio

The Burmese Harp is presented in a very clean full frame transfer (as per its OAR) that's windowboxed but much less severely than other Criterion's titles. Two 35mm fine grain master positives were sourced and this, combined with the digital cleanup, result in a very impressive transfer. The mono sound, from an optical soundtrack print, is also well above average. The optional English subtitles are excellent.

The transfer does beg one question. In its original theatrical release in Japan, The Burmese Harp was first exhibited in two parts. The Burmese Harp - Part 1 (subtitled "Nostalgia Volume") opened on January 21, 1956 with a running time of 63 minutes. Part two debuted three weeks later, on February 12th, with a running time of 81 minutes. Apparently the 116-minute cut of the film, the same one that is on Criterion's DVD, opened simultaneously in other Japanese markets. Whether this two-part version still exists, or what additional footage it might contain, is unknown.

Extra Features

Extras include an Interview with Kon Ichikawa in which the director details his approach to the material. Interestingly he mentions that the film was originally planned for color, but that plan was abandoned because, unlike other studios which were then shooting in Eastman, Agfa, and Fujicolor, producer Nikkatsu Studios was then leaning toward a process Ichikawa calls Konicolor, which sounds like the old three-strip Technicolor process, requiring cumbersome cameras that would have been impractical on location.

Eccentric actor Rentaro Mikuni, whose long career and personality in some respects resembles that of Marlon Brando, likewise appears in an Interview about the film. Both are in 16:9 format. An original Japanese trailer, complete with translated text is also included.

Finally, an 18-page booklet includes an essay by Tony Rayns called "Unknown Soldiers, which offers a nice overview of the film and pointedly notes Japan's still-strained relationship with Asian neighbors it invaded all those years ago, or that Japanese soldiers weren't the benign invaders nor as kind toward Burma's indigenous people as the film likes to suggest. (The famous Japanese character actress Tanie Kitabayashi plays the old Burmese woman that symbolizes this. She reprised the character in Ichikawa's 1985 remake.) Significantly, no mention is made of Mizushima burying or making any effort to bury dead civilians or enemy combatants.

Conspicuously absent are references to Kon Ichikawa's 1985 remake of The Burmese Harp. Although that film was produced by a different company (it was financed primarily by Fuji Television and distributed by Toho), it's a shame Criterion couldn't have included at least a trailer for that version, and certainly could have used a booklet essay comparing the two versions (and perhaps the films with the novel) in greater detail.

Parting Thoughts

Though a contemporary of Kurosawa, Ozu, and Mizoguchi, Kon Ichikawa's career is better likened to that of American director John Huston, who like Ichikawa dabbled in every conceivable genre, and made as many terrible films as great ones. (And, like Huston, he changed with the times and was commercially savvy enough to maintain an extremely long and active career.) The Burmese Harp is then hardly representative but remains one of Ichikawa's finest films.

Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's most recent essays appear in Criterion's new three-disc Seven Samurai DVD and BCI Eclipse's The Quiet Duel.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||