| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Great Jesse James Raid and Other Legendary Outlaws, The

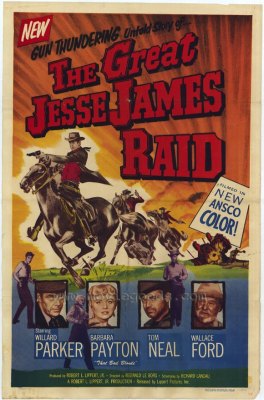

The Great Jesse James Raid (Lippert, 1953)

This not-bad but strange Western opens with Jesse James (Willard Parker) long retired and hiding out living with wife Zee (Barbara Woodell, who plays the wives of both Frank and Jesse in this collection) but still dogged by his legendary outlaw status he reluctantly agrees to join saloon owner Bob Ford (Jim Bannon) and Sam Wells (Richard Cutting) in a scheme to raid a Colorado gold mine by accessing a long-forgotten shaft (Bronson Caverns). Jesse is dubious about the plan and anticipates Ford's intentions to double-cross him, but goes along anyway because he wants to move his family out of the country. They eventually hook up with a Bible-spouting old geezer/demolitions expert (Wallace Ford), a gunslinger (Detour's Tom Neal), and a saloon singer (Barbara Payton).

Oddly, this only screen teaming of the notorious Neal and Payton is downplayed; they share few scenes and her part is small. Given the notoriety of Neal's severe beating of actor Franchot Tone over Payton's affections less than two years before this was released, you'd think lowly Lippert would have played up these troubled stars. (Neal later murdered his subsequent wife, shooting her in the back of the head, while Payton died an alcoholic with a criminal record that included passing bad checks and prostitution.)

Filmed in eye-straining Ansco Color, this odd film suggests something conceived as more thoughtful and ambitious compared to the usual Lippert programmer, but that along the way the budget was slashed and the production was rushed through in the end. The picture was directed by Reginald Le Borg, who had helmed several Universal horror and mystery films in the 1940s and numerous "Joe Palooka" entries after that. He was no great stylist, but the film's crude, almost amateurish transitions suggest something was seriously wrong.

Particularly during the film's second-half, scenes abruptly end with bizarre swish-pans, one looking down at some grass and pavement that might have been the Lippert parking lot. The opening titles, preceded by a gratuitous whipping scene, are crudely painted on a horse and buggy. These are so badly done that the copyright notice is actually obscured by a wagon wheel! (**)

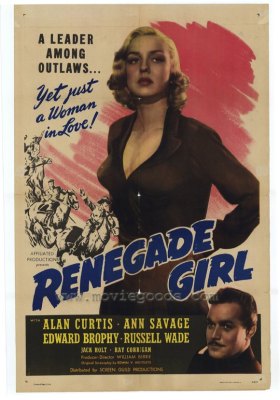

Renegade Girl (Screen Guild Productions, 1946)

The best thing going for this disappointing Western is its star (though second-billed) Ann Savage, the tough-talking femme fatale from the classic no-budget noir Detour and other cheap wartime and early postwar films. Though more than a bit hammy and saddled with a script full of clunker lines generally she's quite good, even memorable in a minor sort of way.

Savage is Jean Shelby, an unofficial scout for Quantrill's Confederate Raiders in Missouri near the end of the Civil War. A ruthless, opportunistic Indian, Chief White Cloud (Chief Thundercloud), murders Jean's brother (who "made Quantrill the man he is") and has a hand in the death of her parents later on, so that after the war she joins some other bushwhackers-turned-outlaws to facilitate her revenge. (He also permanently scarred her with a bullet wound to the shoulder.) Matters are complicated when she falls in love with the Yankee officer (Alan Curtis) charged with capturing her, while the blonde beauty is lusted after be her incredibly horny partners in crime, especially ringleader Jerry (Russell Wade). Indeed, only raider/outlaw Bob (Edward Brophy, in a good performance), who becomes a kind of surrogate uncle, isn't trying to get her in the sack.

The mix of romance and sagebrush and bushwhackers-turned-bandits would be pretty unbearable if not for Savage's engaging performance, even though her wildly inconsistent character - mooning over Curtis one minute, making like Annie Oakley the next - approaches high camp. The rest of the cast includes familiar genre favorites like Jack Holt and Ray "Crash" Corrigan (quite bad as Quantrill), while familiar bad guy Dick Curtis (a favorite of the Three Stooges) has a good scene trying to cozy up to Jean.

The film couldn't have cost more than $25,000 to make nor taken more than six days to shoot judging by the sloppiness of the productions. Actors blow or step on lines that make the final edit anyway. A few shots are jarringly out of focus while the scrubby hills of 19th century Missouri are peppered with visible electrical towers. (**)

Gunfire (Lippert, 1950) and The Return of Jesse James (Lippert, 1950)

Paired on Volume 2 of this set, these films were released a month apart by the same company yet have virtually identical plots. In Gunfire, former outlaw Frank James (Don Barry) is a reformed if ailing pious family man living in Greed, Colorado. Members of Frank's old gang try to woo him back into the fold, but when he refuses they turn to a look-alike hooligan, Bat Fenton (also Barry), to impersonate Frank so that their crimes will be pinned on the real Frank James.

Pretty soon all their victims are dead-certain it's Frank committing the crimes. Only the local sheriff (Robert Lowery) believes Frank to be innocent. Given that the real Frank coughs his way through every scene, walks with overstated methodicalness, and talks with slow Southern drawl while Bat's a lively, fast-talking punk, the deception is pretty obvious.

Gunfire seems to have been shot back-to-back with the similarly uninspired I Shot Billy the Kid (see below), both made by Don Barry's production company for release through Lippert, after short-tempered egomaniac Berry had burned all his bridges at Republic Studios and few were willing to work with him. Both films use real-life Western icons but purely for commercial reasons. Both are singularly unambitious, cheap Bs with just enough gunplay and hard riding to fill genre quotient demands. (**)

In The Return of Jesse James, it turns out that Frank's brother Jesse also has a doppelganger running around besmirching the family name, this time a joker named Johnny Callum (John Ireland), who teams up with members of the old gang and uses the same M.O. as the dead outlaw. Poor Frank James (Reed Hadley), the family unjustly defamed once again, goes after the man impersonating his late brother.

Despite some glaring inconsistencies about Callum's deception and a confused sense of motivation on the part of the leading characters, overall The Return of Jesse James superior in every way, and easily the best film of the set.

For one thing it has by far the best cast. Ireland was a superior actor to, say, Don Barry, and the film chokes with great character players: Henry Hull (as Hank Younger), Hugh O'Brian (as son Lem), Clifton Young and Tommy Noonan (as the Ford brothers, the latter cast against type; his comedy partner Peter Marshall is in the film, too, but I didn't spot him). Victor Kilian and Hank Peterson turn up as lawmen, Byron Foulger, fat Paul Maxey, and I. Stanford Jolley play beleaguered government officials, and so on.

The film has noirish elements, mainly in Callum's relationship with blackjack dealer Sue Ellen Younger (Ann Dvorak), Hank's estranged daughter. Her limitless greed and unscrupulous behavior are a good match for Ireland's egomaniac, whose obsession with tracing and besting Jesse's notoriety becomes a compulsion.

The picture has other good elements, notably the unusual, apocalyptic climax, where an entire town lies in wait for Johnny/Jesse and his gang, supported by better-than-average cinematography by Karl Struss and Ferde Grofe's score, both of whom worked on the moody Rocketship X-M for Lippert that same year.

Other aspects of the film don't stand up to scrutiny. Callum's resemblance to the dead outlaw is bizarrely inconsistent. Some characters peg Johnny for Jesse from afar, at night no less, but when Frank James first meets Callum Frank doesn't even blink. Other characters think Callum a two-bit gunslinger but then mistake him for Jesse when all Ireland does is put on Jesse's old hat and jacket. Still, it's above average for such a cheap Western. (***)

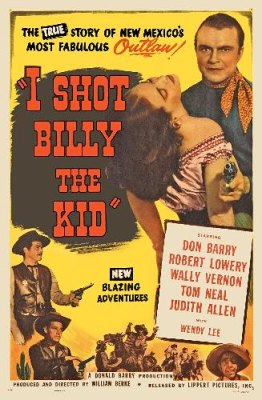

I Shot Billy the Kid (Lippert, 1950)

Barry, Lowery, Vernon, and Neal are all back for this mediocre B that purports to be historically accurate in nearly every detail about William H. "Billy the Kid" Bonney (Barry) and Sheriff Pat Garrett (Lowery). It isn't, though the film may interest fans of better films about their relationship, such as Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973). Though Barry plays Billy with an amused cockiness and Lowery's world-weary Pat Garrett is actually pretty good, the film is basically indistinguishable from other B-Westerns; it's certainly not part of the trend toward "adult Westerns" resulting in part from The Gunfighter, Broken Arrow, and Winchester '73 - all of which, like I Shot Billy the Kid, were released in June and July 1950.

I suspect this and Gunfire (released later that summer) were shot back-to-back. They share the same director, three leads, and the same locations. Vasquez Rocks, a visually striking but greatly overused location not far from Hollywood (about a 40-minute drive into the high desert) is photographed about as unimaginatively and ineptly as possible. Before the film is half over - and it's only 57 minute long to begin with - at least seven times characters are seen riding and re-riding the same stretch of dirt road running alongside the familiar obliquely-angled rocks. What's more, nearly identical, hypnotically repetitive footage turns up in Gunfire, too.

Other production sloppiness pervades the production. When Pat Garrett and his posse (which includes later Detroit movie show host Bill Kennedy) surround Billy's hideout, interior (studio) shots of the front door reveal a scrubby bush just outside and a white wall representing the "sky." This might have worked had the bush not cast a big shadow on the wall, or if members of Billy's gang didn't bump into it. When this footage is cut with a real exterior of the other side of the door, there's an expansive front porch, a door that doesn't match the interior shots, and no bush. (**)

The Dalton Gang (Lippert, 1949)

Don Barry and Robert Lowery are back in another sleep-inducing B, this one trading in on the marquee value of the Dalton Gang, here little more than henchmen working for J.J. Gorman (Ray Bennett), local water & land man. U.S. Deputy Marshal Larry West (Barry) is on their trail, working under the name Rusty Stevens and trading identities with cowhand Joe (Marshall Reed) to infiltrate the gang as one of their hired guns.

Though probably not intended, the film is amusing in that practically the entire cast is hiding behind an alias. Larry's pretending to be Rusty, cowhand Joe is pretending to be Larry, and the Daltons are all using names like "Missouri" Ganz and "Blackie" Mullet.

The picture is strictly by the numbers, white hat (Barry) / black hat (Lowery, as "Blackie" Dalton, no less) stuff, of interest solely for its supporting cast and the occasionally lively direction of busy serial and B-picture helmer Ford Beebe; his direction adds at least a modicum of energy in contrast to his routine script. The film begins with a long montage of newspaper headlines, charging horses and the like: there's no dialogue, everything is conveyed visually, for the first eight minutes and 15 seconds. I don't mean to suggest that Beebe was actually flexing his directorial muscles, and this was probably a way to shave a day and a few thousands dollars off the budget, but this opening goes on for so long and includes moments where Beebe could've stuck a few lines of dialogue I suspect he was having some fun seeing how far he could take this idea.

Luminous Julie Adams makes her first credited film appearance in The Dalton Gang as the typesetter assistant to newspaper publisher Byron Foulger. She's billed here under her real name, Betty Adams, which she'd change to Julia the following year, and then to Julie by 1955. She practically jumps off the screen with her statuesque beauty and natural charm, a real contrast to short and stocky Barry, who looked like a cross between James Cagney and Red Skelton. She'd quickly move onto bigger and better things. (** 1/2)

Video & Audio

All of the films look pretty good considering how cheap and minor they are. The three discs are region-free, dual-layered and single-sided. The audio on all of them tends to be pretty rough, with occasional pops and cracklin', as if VCI never heard of this newfangled invention called noise reduction. Renegade Girl sources a British print (released through Hammer's Exclusive Films) complete with British Board of Film Censors seal and is a bit warpy in the first reel but fine after that. The Dalton Gang is probably the best-looking overall. None of the films have alternate audio or subtitle options.

Extra Features

Limited supplements include annoyingly animated photo galleries and bios of the leading players and directors, along with a few trailers for other VCI titles.

Parting Thoughts

The Great Jesse James Raid and Other Legendary Outlaws is a pretty sorry collection of cheap Westerns of minimal interest, tops. The transfers are pretty good, and a few of them, notably The Return of Jesse James, have their moments. The price is right, so genre fans with a high tolerance for low-budget blandness might want to snap it up.

Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's most recent essays appear in Criterion's three-disc Seven Samurai DVD and BCI Eclipse's The Quiet Duel. His audio commentary for Invasion of Astro Monster is now available.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||