| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

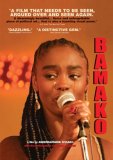

Bamako

The defendants are the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The alleged crime is the grinding down of African society into abject poverty through the systemic practice of granting high-interest loans to African nations, then pressuring those nations to service the loans through reduced spending on basic social services and through the privatization of health care, education, and infrastructure. The sentence sought by the prosecution is community service for mankind for all eternity.

The defendants are the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The alleged crime is the grinding down of African society into abject poverty through the systemic practice of granting high-interest loans to African nations, then pressuring those nations to service the loans through reduced spending on basic social services and through the privatization of health care, education, and infrastructure. The sentence sought by the prosecution is community service for mankind for all eternity.

The trial takes place in Mali's capital city, Bamako. A common courtyard between humble abodes serves as the makeshift courtroom. A pair of bailiffs try to maintain order as daily life continues to flow in and around the proceedings. Some of the background flavor is staged, while much is not. Local residents are engaged in dyeing traditional African clothing, a wedding party gathers, various neighbors wander through the courtyard-cum-courtroom, and one woman demands payment from the chief magistrate to go away. As with Kiarostami's Close-up, the film crew is visibly present throughout the proceedings.

The witnesses for the prosecution are each utterly eloquent in unique ways. The most analytically complete and compelling testimony comes from former Malian Minister of Culture Aminata Traoré. Ms. Traoré marshals facts to support her claim that African has been impoverished by the international financial institutions pressuring the African states to gut their social spending programs to service their debt payments to the first world.

The witnesses for the prosecution are each utterly eloquent in unique ways. The most analytically complete and compelling testimony comes from former Malian Minister of Culture Aminata Traoré. Ms. Traoré marshals facts to support her claim that African has been impoverished by the international financial institutions pressuring the African states to gut their social spending programs to service their debt payments to the first world.

Kenya spends 40% of its national budget on foreign debt obligations, and only 12.6% on social services. The situation is even worse in Zambia where 40% of the budget flows out of the country to service debt, but only 6.7% of the budget is allocated for social services. Ms. Traoré compellingly argues that this scheme by which money flows out of Africa and into the rich northern hemisphere nations is impoverishing Africa.

To a claim by the defense attorney that she's ignoring the beneficial forgiveness of loans provided by the World Bank and IMF, Ms. Traoré provides three rebuttals: (1) Africa has already repaid the original loans many times over; (2) the original loans were illegitimate because they were not used to benefit the people; and (3) partial debt forgiveness is merely a method of accounting which slows the flow of wealth out of Africa, but does nothing to infuse money into education, health care, or job creation.

An unemployed school teacher is left speechless by his effort to put into words the harms that the defendants have done. Another witness forcefully talks of the despair growing in Africa that fuels hatred and immigration, while the final witness holds forth in a three-minute lamentable chant that is not subtitled but is utterly clear in its sincerity and depth of feeling.

In addition to the trial and the ordinary daily life taking place in the courtyard, there are a couple other small scripted stories which serve to segment the central storyline. These are interesting but fairly simple asides, with one exception: a television broadcast of a neo-spaghetti western called Death in Timbuktu. This movie-within-a-movie stars Danny Glover and Palestinian actor and filmmaker Elia Suleiman. The inclusion of this bogus film may leave some viewers scratching their heads, but it's really nothing more than a satirical look at northern sensibilities and entertainments through African eyes.

In addition to the trial and the ordinary daily life taking place in the courtyard, there are a couple other small scripted stories which serve to segment the central storyline. These are interesting but fairly simple asides, with one exception: a television broadcast of a neo-spaghetti western called Death in Timbuktu. This movie-within-a-movie stars Danny Glover and Palestinian actor and filmmaker Elia Suleiman. The inclusion of this bogus film may leave some viewers scratching their heads, but it's really nothing more than a satirical look at northern sensibilities and entertainments through African eyes.

Bamako was written and directed by Abderrahmane Sissako who is frequently likened to the late African auteur Ousmane Sembene (Black Girl, Moolaadé). The association is justifiable. Both Sissako and Sembene received their formal training as filmmakers in the Soviet Union; both are pan-African, post-colonialists who imbue their films with their politics; and, both are also immensely talented.

The Video:

For a New Yorker Video release, Bamako's image is actually very good. Shot originally on 16mm, the transfer is bright with well-rendered deep color saturation. Though interlacing is noticeable, the combing is not overly distracting.

The original 1.85:1 image is resized to 1.78:1 for DVD, and enhanced for widescreen.

The Audio:

The French and Bambara audio mix is available in 2.0 and 5.1 Dolby Digital. Both render the dialogue well with no noticeable dropouts or distortion and both provide good separation between the right and left front channels. The 5.1 falls a bit short in providing a robust soundscape, but it's a good effort.

The optional English subtitles are adequately translated, sized, paced, and placed.

The Extras:

The extras include a 10-page booklet, the theatrical trailer, and a number of interviews: Harry Belafonte (5 min.); filmmaker Adberrahmane Sissako (36 min.); executive producer Danny Glover (7:30); Yao Graham, with the NGO Third World Network Africa (16 min.); and, Professor Gita Sen (10 min.).

Final Thoughts:

Bamako is an important film with a compelling narrative and innovative style. It deserves to be seen by a wide audience. Nevertheless, a bit of warning is due. There's none of the antics of traditional courtroom dramas here, and what distractions there are from the case in this 117-minute film may strike some viewers as perplexing. While familiarity with post-Soviet neo-realist world cinema is helpful to fully appreciate Bamako, the only prerequisite to enjoying this innovative film is an open mind.

Adberrahmane Sissako's Bamako is highly recommended to fans of world cinema.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||