| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

John Wayne: The Fox Westerns (The Big Trail 2-Disc Editon, North to Alaska, The Comancheros, The Undefeated)

20th Century-Fox has released John Wayne: The Fox Westerns, a four film, five-disc boxed set that gives us one bona fide classic, one very entertaining comedy western, and two rather marginal later action westerns, starring the most famous actor in American motion picture history. All of these films have appeared on disc before, so double-dipping isn't necessary - unless you have the old The Big Trail disc that features the 35mm version - John Wayne: The Fox Westerns contains the new two-disc special edition of this amazing epic, including the anamorphically enhanced 70mm Grandeur version. Let's look at the individual films.

THE BIG TRAIL

An unique milestone in the western genre (the first shot in a wide gauge format), 1930's The Big Trail is notable not only for the groundbreaking use of the 70mm Grandeur process, but also for giving Marion Morrison, a bit player and furniture mover on the Fox lot, a new name - John Wayne - and a start (however bumpy) to his illustrious film career. Conceived by Fox studios as a big-budget "hail Mary pass" to save the rapidly spiraling fortunes of its founder, William Fox, the box office failure of The Big Trail did little to elevate the western genre out of the B-ranks, while putting the first pause in Wayne's rise to stardom. Pictorially overwhelming to this day, The Big Trail is a most unusual viewing experience, recreating - with the use of the most advanced, cutting-edge technology at that time - a surprisingly realistic, epic-scale depiction of the settling of the West that works precisely because it is simultaneously ultra-modern and primitive in its execution and intent.

Wayne plays Breck Coleman, an Indian-trained scout who is trying to track down and kill the "pair of skunks" who murdered his trapper friend Ben Grizzel for his wolf pelts. In Independence, Missouri, he meets up with his friend Wellmore (William V. Mong), who has organized a wagon train for settlers heading west. Asked by Wellmore to track and guide for the train, Breck initially turns him down, until he suspects that the train's bull whip, Red Flack (Tyrone Power, Sr.) and his sidekick Lopez (Charles Stevens) are the culprits behind Ben's murder. It doesn't hurt, either, that Breck has met the beautiful Ruth Cameron (Marguerite Churchill), who along with her brother and younger siblings, intends on settling in the wild northwest.

Sensing that he can execute his frontier justice at the same time he romances the beautiful Ruth, Breck changes his mind and agrees to scout for the wagon train, taking along his trail buddy Zeke (Tully Marshall). This is obviously bad news for Red Flack and Lopez (who quickly realize that Breck is suspicious of them), but also for Louisiana card shark and bounder Bill Thorpe (Ian Keith), who hopes to swindle Ruth into marrying him, promising her a non-existent plantation back home. Thorpe soon teams up with Red Flack and Lopez to take out Breck along the trail. Will Breck survive the various murder attempts by the evil gang, while guiding the settlers along the hostile 2,500 mile trek?

Directed by action specialist Raoul Walsh, The Big Trail makes up for its creaky dialogue scenes with action sequences of spectacular scope and dimension. What I found most dynamic and aesthetically curious about watching the film was realizing that in their effort to bring The Big Trail to the screen, the filmmakers were using cutting-edge technology to convincingly recreate a past...that wasn't all that "past," if you will. Capturing vast, panoramic vistas that today might very well be impossible to find in the U.S., due to encroaching civilization in even our most remote spots, The Big Trail looks and feels almost like a documentary because you realize that the filmmakers didn't have to alter too much of their locations to capture its set pieces. And yet, when watching the film today, its sometimes velvety black and white cinematography (a rare combination with the choice of 70mm widescreen for the western genre), its use of silent film intertitles, and with the tell-tale early talkie acting, The Big Trail has a self-reflexive patina of quaintness, of artifact in and of itself. It was an envelope-pushing technological effort in its day, recreating a past, undisturbed world that was still discernable to its chroniclers, that now plays like an faintly ancient relic. Fascinating layers of audience perception and viewing experience.

The story of an indefatigable group of pioneers pushing ever onward west, despite the most cruel hardships and loss, is of course a verboten message in today's sickly P.C. lock-down. Anything that smacks of acknowledging the true tenacity, courage and intestinal fortitude of early frontier pioneers and settlers is either deemed naive or downright racist - which seems ironic when you listen to Breck defend the Indians with whom he lived, telling the young children who are ignorant of Indian ways how smart and admirable that are as a people - sentiments that modern film historians are loathe to admit are present in films from this period. Obviously, these current "political" concerns were not the concerns of the filmmakers of 1930's The Big Trail, but I wonder if the subtext of the never-say-die pioneers was not-so-subtly aimed at the Depression-era audiences who were in the throes of the deepening world-wide crisis. Read Wayne's big speech near the end of the film, when the settlers are about to chuck it all in:

We can't turn back! We're blazing a trail that started in England. Not even the storms of the sea could turn back those first settlers. And they carried on further. They blazed it on through the wilderness of Kentucky. Famine, hunger, not even massacres could stop them! And now we've picked up the trail again. And nothing cans stop us - not even the snows of winter, not the peaks of the highest mountains! We're building a nation! But we've got to suffer! No great trail was ever blazed without hardship. And you gotta fight! That's life! And when you stop fightin', that's death! What're you going to do? Lie down and die? Not in a thousand years! You're going on with me!

That sounds as much like a rallying cry for a country knocked down on its knees (The Big Trail premiered exactly one year after1929's Black Thursday), as a validation of Manifest Destiny.

The Big Trail's action scenes, obviously the highlights of the film, are a marvel to this day. Seen on a big monitor (obviously not the ideal way - a 70mm-equipped theatre would be - but still far more impressive than the film's alternative 35mm version, shot at the same time, which showed up frequently on TV), The Big Trail's incredible set pieces are quiet dynamic in terms of foreground/background perspective, where wagon trains roll through the dust while activity by hundreds of extras can be seen miles off into the distance. Even with the sometimes scratched print, the verisimilitude of these kinds of scenes, not tricked photographically in any way, make current CGI effects look just like what they are: cartoons. Walsh's tableaux can be static (owing no doubt to the difficulties of staging action and dialogue with the new sound recording equipment as the prime technical consideration), but they still have a power and solidity to them that reminds me at times of David Lean. The film's highlight has to be the sequence where massive Conestoga wagons are cantilevered over a huge precipice with primitive block and tackle. Not content to just have a one wagon at a time hauled over, Walsh stages all the wagons going over at the same time, on a large, curved cliff. And to "top" the sequence, he has the settlers scuttling down a long rope amid the wagons. It's a tremendous visual, one that impresses as much for its feat of engineering as for its thematic energy.

Obviously the other noteworthy aspect of The Big Trail is the introduction of Wayne to the viewing public in his first starring role. Anyone familiar with the Duke throughout his career who hasn't seen The Big Trail will be taken aback at how young and handsome he looks here. Only 23, Wayne is no accomplished thespian, to be sure, with the distinct awkwardness of a newcomer who doesn't know what to do with his body or his voice. But tellingly, at certain moments where he moves just right or gives a faint hint of that remarkably distinct cadence that would characterize his performances in the coming decades, you can just see the iconic Wayne that will become for the world, the most recognizable symbol of the American west. Evidently, Wayne was picked by Walsh because he wasn't like the New York trained theatre actors all the studios were recruiting for talkies; they knew beforehand that he was untried and stiff, but the producers felt those qualities were perfect for the role. That, and the fact that no other established western star was available made Wayne seem like a natural. It's become legend that Wayne was immediately relegated to Poverty Row B-westerns when The Big Trail failed, but Fox didn't give up on the fledgling actor right away, starring him in two modestly-budgeted vehicles (neither one a western) after The Big Trail tanked, before finally letting him out of his contract. Ironically, his subsequent long, long tenure in low-budgeted, quickly ground-out oaters where he learned his craft the hard way - the polar opposite of The Big Trail's production - finally secured him the stardom that he expected in one fell swoop from this first western starring role.

NORTH TO ALASKA

Warmly received by critics and a big hit with the public (no doubt aided by that insanely catchy title tune by the great Johnny Horton), North to Alaska, according to its director, Henry Hathaway, was conceived and shot in absolute chaos, but ironically in its success with ticket buyers, it set the pattern for many later Wayne pictures, where comedy was introduced to help smooth Wayne's transition over to a more mature leading man icon. Wayne stars as Sam McCord, a "mighty man" in the year of 1900 who has successfully hit it rich with a gold strike right outside of Nome, Alaska. Flush with cash, Wayne sets out to return to Seattle and bring back his partner George Pratt's (Stewart Granger), fiance to marry (Sam is also buying heavy equipment for the mine, and that's why he's sent instead of George, who will guard against claim jumpers).

Once in Seattle, however, Sam discovers that George's fiancé has already married, so Sam, in a moment of inspiration at a whorehouse, decides that one "Frenchie" is as good as another. Meeting Michelle (Capucine), a French prostitute at the Hen House brothel, Sam offers her the chance to marry a millionaire in Alaska. She agrees, but after Sam treats her so well (including a side journey to a loggers' picnic, where Sam defends her honor against the loggers' disapproving wives), Michelle forgets that Sam's offer was for her to marry George, not him - a notion he disavows, setting her straight on the boat ride back to Alaska. Once there, Michelle decides to capture her man, regardless of his strong anti-marriage stance, but she runs into trouble when former pimp Frankie Canon (Ernie Kovacs) makes his presence known, as well as when she has to fight off the advances of George's little brother, Billy Pratt (Fabian).

SPOILERS ALERT!

Set up strictly as a "deal picture" for producer Charles Feldman to get his then-girlfriend Capucine into a John Wayne picture, North to Alaska didn't even have a finished script when cameras began to roll in 1960. The original director, Richard Fleischer, jumped ship when no script was produced for his perusal, and a writers' strike squashed any chance for the filmmakers to finish up the barely outlined plot prior to shooting. According to accounts, most of North to Alaska, then, was improvised and stretched out on the spot, during filming, with the resulting picture having quite a bit of light, fluffy charm to it, but understandably, not much substance at its core.

And you can see the seams all over the place. The picture opens and closes with wild, cartoonish brawls (not a bad way to set up and send off audiences, which must have certainly helped word-of-mouth), while the middle section has a long, drawn out (but highly enjoyable) set piece at a logger's picnic - all signs of the filmmakers padding out the shapeless film. Those brawls are real highlights, though, containing a bouncy, cartoon-like tone, complete with silly sound effects and outrageous sight gags (the two goats aiming for Granger and butting heads, in full CinemaScope close-up glory, is probably the film's funniest gag), that opens and closes the film on energetic highs. What looks scripted - the Ernie Kovacs character (who mysteriously disappears throughout the film, only to pop back up again at the end), along with the bedroom farce second act - isn't nearly enough to support a feature film (and which, funny enough, seems a tad heavier than the lighthearted brawling and boozing scenes).

Alongside westerns and spy films, sex comedies were one of the dominant film genres of the 1960s, and it's interesting to see elements of that form stuck in the middle of a lusty John Wayne western. The middle section of the film, where George, Billy, Sam and Michelle are isolated in their two little cabins up in the hills by a small stream, plays very much like any bedroom comedy from that period, with deliberate misunderstandings, romantic posing (George pretending to make love to Michelle - loudly - to get Sam mad), and kicked in bedroom doors, all making this section of North to Alaska feel almost Doris Day-ish in tone and execution. Wayne, whom I always wished had donned a three-piece suit and played in one of those types of films from that period, is quite adept at getting the tempo right for this kind of romantic comedy timing (he's quite funny, gradually flipping out while sitting at a table, listening to George and Michelle "making love"). Wayne, coming directly off his soon-to-be critical and financial debacle The Alamo, is quite loose here, not afraid to pull a mug when needed. Evidently, Wayne was grateful for the chance to leave the stress and strain of guiding so huge a project as The Alamo behind him, and it shows with his nicely counterbalanced mixture of traditional Wayne he-man knuckle-dusting, and surprisingly deft romantic comedy star. It's not an element fans of Wayne were expecting from their favorite star in 1960, and it seems to fit right in with the fluffier aspects of early 1960s Hollywood comedies.

Granger has a fairly humiliating role here (he plays a loser who when presented with another girl gets rejected by her, only to help her land his best friend), which he can't do much with; his scenes with Capucine where he tries to convince Sam they're having a ball, aren't pulled off very well, which may have as much to do with Capucine's rather chilly charms as Granger's inept comedy skills. Capucine is beautiful to look at, but I can't quite picture her as an experienced New Orleans whore, nor does she seem to get into the spirit of the picture; this role needed a flesh-and-blood woman, not a Givenchy dress dummy (evidently, Wayne privately stated he despised her). Fabian, on the other hand, is agreeably goofy as horny-as-hell Billy, particularly when he's trying to impress Michelle during their dinner. Believably awkward and over-confident at the same time, he's quite funny as he spastically tries to contain himself around the beautiful Michelle. As for Kovacs, I wish he was better integrated into the film; he's such an oily, acerbic counterpoint to the wide-open Wayne that his disappearance during the long cabin/bedroom farce section takes the wind out the character. When he's reintroduced, we almost forget about his rigged claim-jumping scheme, and his final appearance in the big main street brawl seems almost like an afterthought. Still, despite problems with the script and some questionable casting, North to Alaska is one of the better Wayne comedies, and an important departure point for a star transitioning to older leading roles.

THE COMANCHEROS

A big, popular winner at the box office in 1961, The Comancheros marks a further departure for Wayne's long-tendered cinematic persona. As North to Alaska showed the Duke could be funny, The Comancheros transitioned Wayne into the older lead hero/almost character actor who didn't necessarily "get the girl." Wayne plays Texas Ranger Captain Jake Cutter, who's been directed with picking up Louisiana fugitive Paul Regret (Stuart Whitman), who is to be extradited for killing a judge's son in a duel. Regret had become involved with Pilar Graile (Ina Balin), who pursued him when she spotted Regret on the river boat that was taking them Galvaston, but she disappeared once Regret was taken into custody by Jake.

Traveling by horse through Texas (where a Louisiana sheriff waits to pick up Regret), Regret tries several times to escape Jake's custody - and succeeds - only to be brought back again. Regret, friendly enough with the distrustful Jake, proves himself as courageous when he helps settlers and the Rangers fight off a Comanche attack - one fueled and led by Comancheros (renegade whites working with the Indians in criminal endeavors, such as gun running). Saving Regret from returning to Louisiana (where he would most certainly hang), Cutter and his fellow Rangers swear that Regret was a Ranger at the time of the duel - as long as Regret becomes a Ranger for real. His first assignment? To travel with Jake and find out where the Comancheros' secret base is in the desert, and smash the crime ring.

SPOILERS ALERT!

According to several sources, the production of The Comancheros was strained due to director Michael Curtiz's terminal cancer. Evidently, Wayne soon took over the directing chores (although he refused co-directing credit), but it's obvious that the film's direction is compromised by a fitful, stop-and-go rhythm that makes this long, long film take forever to get going. That tentative, disjointed feel to The Comancheros may well stem from the long-winded script, as well. There's a lot of yakking in what's supposed to be an old-fashioned rip-snorter. Wayne and Whitman dodge and weave about, trying to get the upper hand on each other (although not nearly in as a compelling or humorous manner as say, Cooper's and Lancaster's Vera Cruz), but often or not, they're reciting dialogue, not riding or shooting. When the occasional action sequence does crop up, it's not particularly memorable or distinguished (both of the major Indian attacks are choreographed in an almost identical manner), and then the film stops again while everyone chaws at each other.

As well, there are major problems with the script's construction that seriously compromises The Comancheros. Particularly troubling is the whole Pilar/Regret set-up, which, unless I missed something, doesn't seem to make much sense. The film is careful to build up Pilar's mysterious interest in Regret, going so far as to have her father's henchman (and perhaps her bodyguard/lover?) find out who Paul is, and what he's doing on the boat (by the way; what is she doing on the boat?). She then brings him to her room, and discusses desire, not love, with him, and presumably sleeps with him. Regret believes her first to be part of a blackmailing scheme, but when she says denies this, he's suspicious of her just picking him out from everybody else on the boat, for the purposes of sex. Her disappearance before he's hauled off by Jake furthers her mysterious behavior. The way this opening sequence is structured, you expect her to have some kind of ulterior motive for ensnaring Regret, but...she doesn't. And yet when Regret comments several times that he's incredulous of her randomly picking him to have a romance, she says, to some effect, "Don't flatter yourself." Huh? Well, what is it? Is it sex or some other reason? We never find out.

Even worse, once we get to Pilar's father's (Nehemiah Persoff) hideaway, we're told in ominous tones that this is Graile's private civilization, where there's only one rule: "Transgress, and you die." But this supposedly wicked outpost of killing Comancheros and drunken, rowdy Comanches, ruled by a ruthless killer, is never believable for a second because the script does nothing with the possibilities of such a place, nor is Persoff even remotely suited to the role. Confined to a wheelchair, Persoff barely raises his voice, which would be fine, if he emanated even a modicum of threat or violence or evil or twisted perversity or anything - which he fails miserably to do. Evidently, Eli Wallach was busy, because the producers obviously are trying to go for the same kind of character Wallach played so well in the previous year's hit, The Magnificent Seven (aided, as well, by Elmer Bernstein's similar-sounding theme), but Persoff is ill-suited to the task. The film, just when it finally seems like it's going to achieve lift-off, stops dead in its tracks, and the promise of this violent, secret city in the desert, is completely muffed.

At least some of the performances in The Comancheros make the time passing a little more agreeable. Whitman, compact and handsome next to mountain Wayne, can't quite seem to get a handle on his character (no doubt due to the script, not Whitman's considerable thesping skills), but he moves well within the western milieu, and has a nice cultured counterpoint to the brawling, strong-but-silent Wayne. Balin has the oddest delivery here, biting off each word in a sentence with the eagerness of a student in an elocution contest, but thankfully, Lee Marvin shows up for a (criminally) short time as Tully Crow, giving The Comancheros a king-size jolt of sullen viciousness and energy that makes everything the comes before and after it seem wane and colorless (unfortunately, the new technology of DVD and widescreen big monitors makes that scalped skull makeup of his look quite ridiculous; growing up, that looked pretty convincing on a small b&w portable). As for Wayne, well...he's Wayne. He doesn't have much to do here as far as real acting (this isn't The Searchers by about ten miles), but he's so effortlessly comfortable inhabiting his on-screen persona that it doesn't really matter that the character - despite the clumsy exposition revealing his past - is basically a cipher. Over the next decade, as Wayne aged dramatically, this is the world-weary, hardened Westerner he would present in a series of increasingly marginal films (until his penultimate, finest performance in The Shootist).

THE UNDEFEATED

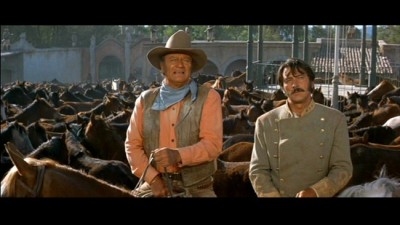

Running in the same scattershot vein as The Comancheros, The Undefeated is a distinct let-down here for the Duke, a pretty poor excuse for an "Americans-fighting-south-of-the-border" western that isn't enlivened in the slightest by the plot novelty of having former Confederate and Union troops uneasily fighting together against the Mexican bandits and soldiers they meet up with during their long, long travels down Mexico way. Duke stars as John Henry Thomas, a Union colonel who discovers that for three days, he's been fighting a war that was already declared over and won. Incredulous that the Rebel force he's been battling has known the same news for a least a day prior, he returns to his military post and resigns his commission. His aim is to take his men to the New Mexico and Arizona territories and procure horses for the U.S. government. The war is over for him.

For Colonel James Langdon (Rock Hudson), the war will never be over. Going bust by financing his own regiment during the War Between the States, plantation owner Langdon now means to take his people - including his family - and emigrate to Mexico, where he has been invited by the Austrian-born emperor Maximilian (put on the throne by Mexican monarchists and the French government) to live and work for the unpopular government. It's a 2,000 mile journey for the group, through Union-occupied territory, and then through the harsh Mexican outback, where bandits and rebel forces led by Benito Juarez, wishing to overthrow the emperor, lay in wait.

Once John Henry rustles up 3,000 head of horses, he finds out the U.S. government only wants 500 (and at a lower price), while officials from the Mexican government will buy all of them at top dollar. Soon, John Henry and his men are on their way to Mexico, running the horses for Maximilian, where they meet up several times with Langdon's Confederate group. Of course, conflict erupts both from within the two groups' dynamic, and with outside forces, causing no end of trouble until there's a final showdown for all concerned.

SPOILERS ALERT!

The Undefeated was shot immediately after Wayne completed principal photography on True Grit, and was released in September of 1969, following True Grit's June release. Coming so closely after that masterpiece, it's difficult not to view The Undefeated unfavorably by comparison, particularly since The Undefeated is such a lazy, ill-conceived, artless affair in and of itself. Evidently, Wayne was committed to The Undefeated prior to securing True Grit, and he was concerned the project would be considered old-fashioned and out of touch in comparison to the more modern, violent spaghetti westerns (starring the much younger Clint Eastwood) that were pulling in big money at theatres and drive-ins (1969 would also see the release of Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, which would expand on the genre even further). The Undefeated made money (about $14 million worldwide, a good gross then), but True Grit made that much in the States alone, so Wayne was correct in his prediction that The Undefeated wouldn't be a standout in his career.

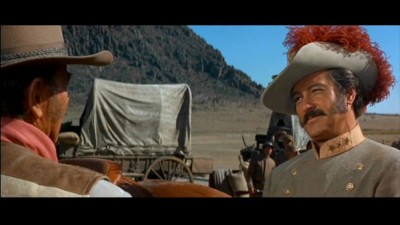

Using good friend Andrew V. McLaglen for the directorial chores (the very definition of "studio journeyman" if there ever was one), Wayne, looking overweight and unhealthy (he suffered two serious injuries during the shoot), had total control over the project and so surrounded himself with old pals in the cast, while he brought aboard newcomer Rock Hudson (?) for the role of the Confederate colonel. Now I'm a fan of Hudson's (his Doris Day films are terrific, and he was unforgettably brilliant in Frankenheimer's masterpiece, Seconds), but he is woefully miscast here, looking frankly ridiculous in that plumed hat and handlebar moustache (his Southern accent is the same one he used in Pillow Talk. It's funnier here. And it's not meant to be). Evidently, Hudson and Wayne got along like a house afire behind the cameras, but curiously, they have almost no chemistry together on screen, no spark, with Hudson more often than not put discreetly in the background or shot over-the-shoulder to favor Wayne. Hudson later said he owed Duke for giving a jump start to his moribund career - but he also admitted that The Undefeated was junk.

It's not that the basic premise of The Undefeated is uninteresting - it's just that screenwriter James Lee Barrett (The Green Berets, Shenandoah) and director McLaglen make it so by their absolutely rote, colorless approach to the material. Never clearly establishing what Hudson and his group hope to find down in Mexico in the first place, we have a hard time caring if they make it or not. And the seemingly endless back-and-forth meetings between the two groups (complete with a phony Fordian Fourth of July picnic dust-up between the happy-go-lucky lugs) begin to get tiresome fast, particularly since the action isn't distinguished in the least.

Surprisingly flat compositions and color from Wayne regular, cinematographer William Clothier, denies us even the basic visual pleasures of an otherwise crappy Western, while Hugo Montenegro's thin, dull theme and score well up at the oddest times, obviously used to shore up the uninspired visuals. And criminally, there's no climatic payoff to the film! When Hudson has to go begging to Wayne for his horses, or have all his people shot (Hudson and his group are taken prisoners by Juarez' men, who conned them by pretending to be with Maximilian), Wayne and his men agree...and then they deliver the horses. That's it. No shoot out. No argument. Not even a cross word. The movie ends with Wayne and Hudson riding off, laughing. Was this plot resolution a way for the Wayne character to slip out of supporting the wrong guy, Maximilian? Hard to say, but as the final credits role, and you're asking yourself, "Is that it? Are they just going to give in without a fight?", you can imagine 1969 audiences saying the same thing.

The DVD:

The Video:

The transfers for all of the films in the John Wayne: The Fox Westerns collection are the same as their earlier DVD releases. The Big Trail looks, at times, the best and the worst of the collection; there are sequences where scratches and other print anomalies are quite prevalent, but many more where the velvety 70mm black & white cinematography (anamorphically enhanced for this DVD in a 2.10:1 widescreen aspect ratio) is startlingly clear and crisp. North to Alaska, in an anamorphically enhanced 2.35:1 widescreen transfer, is quite bright (if at times somewhat faded in spots), with generally good skin tones and minimal grain. The Comancheros, in an anamorphically enhanced 2.35:1 widescreen transfer, has considerably more grain, as well as a slight yellowing to the skin tones, but the picture is sharpish. And The Undefeated, in an anamorphically enhanced 2.35:1 widescreen transfer, looks as good as it can, considering the indifferent original photography. Grain is minimal, but the picture does look somewhat soft at times.

The Audio:

The Big Trail features a Dolby Digital 2.0 "stereo" cheat mix, and the original 1.0 mono, which, taking into account the primitive recording methods available at the time, sounds thin. English and Spanish subtitles are included. North to Alaska, The Comancheros, and The Undefeated all offer nicely spread-out (but unexciting) 4.0 Dolby Surround mixes (Johnny Horton really needs to be heard in 5.1), along with French and Spanish mono tracks. English and Spanish subtitles, and close-captions are available.

The Extras:

The Big Trail two-disc special edition is the only title here with substantial extras. First, there's a feature length commentary track by Richard Schickel. Schickel always comes off to me as alternately bored and contemptuous having to discuss film - as if it's a chore to have to actually explain things to us mere mortals. He can lay off conducting these commentaries - filled to the brim with generalities - anytime he feels like it. The Big Vision - The Grandeur Process, running 12:10, features historians and technicians discussing the Grandeur process (fairly basic for anyone already familiar with the process). The Creation of John Wayne, running 13:55, is a brief bio of the star, along with some theories concerning his on-screen persona throughout his varied career. Raoul Walsh: A Man in his Time, running 12:25, looks at the action director's career, touching in more detail his time on The Big Trail, while The Making of The Big Trail, running 12:29, gives more detail about the behind-the-scenes production - none of which are of the fun kind that I've read about, including all the drinking and whoring around that commenced once the company hit the road. Too bad. North to Alaska features a short newsreel snippet that shows Fabian arriving at the Broadway premiere of the film - no other stars are featured (perhaps they arrived later? Or not at all?). There's also the original trailer. The Comancheros has an even stranger little newsreel showing Claude King and Tillman Franks receiving an award for the song featured in The Comancheros...which isn't featured in the film (perhaps left out for license reasons on the DVD?). The original theatrical trailer is included. And The Undefeated contains the original Portuguese and English trailers.

Final Thoughts:

Two of the films featured in the John Wayne: The Fox Westerns collection are at the least recommended viewing, with The Undefeated not really even worth a rental, unless you're a die-hard Wayne fan (like myself). Certainly the chance to see the epic The Big Trail in 70mm should secure a buy for this collection alone, but North to Alaska does provide some solid pleasures. It's a mixed bag, and owners of the previous DVD releases need not double dip, so I'm going to only recommend the John Wayne: The Fox Westerns.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||