| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Glitterbox: Derek Jarman x 4

He was the material of his own work."

- Tilda Swinton

The MAN

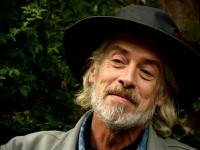

Avant-garde, underground, experimental...you name it, Derek Jarman helped define it. A painter, a poet, a gay rights activist, a filmmaker--he combined all of his passions together when he picked up a video camera, an artist in every sense of the word. Frequently experimenting with Super 8mm film, he challenged the way viewers interpreted movies, and frequently infused his works with his own style of "gay filmmaking". This new four-disc set presents four of his films--two art house, two avant-garde--available on DVD for the first time (Carvaggio and Wittgenstein will also be released separately; The Angelic Conversation and Blue are exclusive to this set).

The MOVIES

Caravaggio (1986)

Largely considered one of Jarman's most successful efforts, this 1986 biopic chronicles the life of 17th Century Italian painter Michelangelo Caravaggio--a sometimes controversial artist who led a tumultuous life, one exacerbated by his fame. The film starts on July 18, 1610 as the artist (brilliantly played by Nigel Terry) lies on his deathbed: "Four years on the run--so many labels on the luggage, and hardly a friendly face." Attended to by his loyal assistant, the mute Jerusaleme (Spencer Leigh), Caravaggio reflects upon his life, taking us back in time: "I built my world as divine mystery...found the god in the wine and took into my heart. I painted myself as Bacchus and took on his fate: a wild, orgiastic dismemberment. I raise this fragile glass and drink to you, my audience...man's character is his fate."

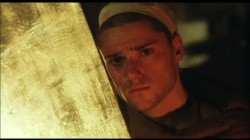

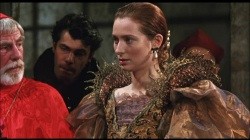

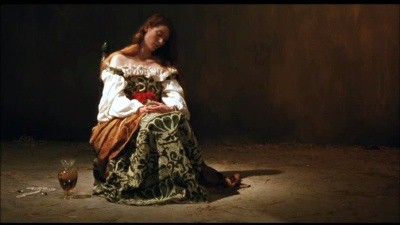

We see his exploits as a young man (the motto engraved on the blade of his knife: "No Hope, No Fear"), with his budding sexuality catching the attention of strangers ("I'm an art object--and very, very expensive...") as well as mentor Cardinal Del Monte (Michael Gough). We soon jump to a later stage in his life, where the bulk of the story unfolds as the painter eyes a new muse: a young, dashing fighter named Ranuccio (Sean Bean), who sees an opportunity to pay off his gambling debts when Caravaggio comes calling. Their relationship disturbs his girlfriend Lena (Tilda Swinton, in her first movie), but when she provides her own inspiration for the artist, the story escalates into a hauntingly beautiful Greek tragedy.

We see his exploits as a young man (the motto engraved on the blade of his knife: "No Hope, No Fear"), with his budding sexuality catching the attention of strangers ("I'm an art object--and very, very expensive...") as well as mentor Cardinal Del Monte (Michael Gough). We soon jump to a later stage in his life, where the bulk of the story unfolds as the painter eyes a new muse: a young, dashing fighter named Ranuccio (Sean Bean), who sees an opportunity to pay off his gambling debts when Caravaggio comes calling. Their relationship disturbs his girlfriend Lena (Tilda Swinton, in her first movie), but when she provides her own inspiration for the artist, the story escalates into a hauntingly beautiful Greek tragedy.

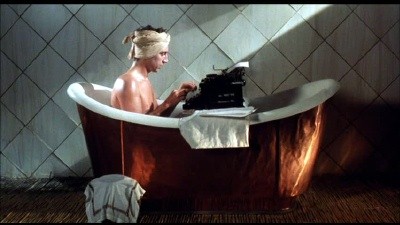

A labor of love for Jarman, this film was seven years in the making and constructed on a very low budget in a London warehouse. It's remarkable what he was able to create, aided by the superb skill of cinematographer Gabriel Beristain, production designer Christopher Hobbs and costume designer Sandy Powell. It proves that passion--not money--counts the most. The sets are simple yet striking, taking advantage of effective lighting (much like Caravaggio's paintings) to tell the story. A painter himself, Jarman's film is its own work of art--a personal portrait of an artist, a rebel--and a man in love. He makes effective use of bold imagery: a snake on a basket, shadows on a wall and any scene that brings Caravaggio's paintings to life, and uses sound to suggest grander surroundings. Jarman also opts for some anachronisms: a calculator, a typewriter, a motorbike and various costumes evoke a later period, a playful choice that perfectly suits the film's tone.

A labor of love for Jarman, this film was seven years in the making and constructed on a very low budget in a London warehouse. It's remarkable what he was able to create, aided by the superb skill of cinematographer Gabriel Beristain, production designer Christopher Hobbs and costume designer Sandy Powell. It proves that passion--not money--counts the most. The sets are simple yet striking, taking advantage of effective lighting (much like Caravaggio's paintings) to tell the story. A painter himself, Jarman's film is its own work of art--a personal portrait of an artist, a rebel--and a man in love. He makes effective use of bold imagery: a snake on a basket, shadows on a wall and any scene that brings Caravaggio's paintings to life, and uses sound to suggest grander surroundings. Jarman also opts for some anachronisms: a calculator, a typewriter, a motorbike and various costumes evoke a later period, a playful choice that perfectly suits the film's tone.

Jarman is able to convey not only the painter's passion, but his own as well: "All art is against lived experience," says Carvaggio. "How can you compare flesh and blood with oil, ground, pigment?" Bean runs away with the film, a smoldering presence that oozes sexuality and pops off the screen (I loved the final sequence with Carvaggio and Ranuccio). He and Swinton are perfectly cast, (literally) shining in their roles. The camera loves both of them, and countless shots leave no doubt as to how they put the artist under their spell.

Jarman has noted that when it was first suggested he make a film about Caravaggio, he knew very little about him--much like I had little knowledge of Jarman's work. This was a beautiful introduction (this film hasn't aged a bit) and quickly whetted my appetite for more.

Transfer:

Restored from high-definition elements, the anamorphic 1.85:1 transfer still shows age but looks beautiful. This is a warm presentation, bathed in dark shades and very soft. It's a beautiful choice to convey Caravaggio's work and life. There's mild grain and occasional candle-like flicker lighting (which sometimes seems intentional). The 2.0 stereo track (with optional English subtitles) is one of the more robust ones you'll find, making good use of the film's modest yet powerful sound effects.

Restored from high-definition elements, the anamorphic 1.85:1 transfer still shows age but looks beautiful. This is a warm presentation, bathed in dark shades and very soft. It's a beautiful choice to convey Caravaggio's work and life. There's mild grain and occasional candle-like flicker lighting (which sometimes seems intentional). The 2.0 stereo track (with optional English subtitles) is one of the more robust ones you'll find, making good use of the film's modest yet powerful sound effects.

Extras:

Leading the way is a collection of four video interviews (30:22), led by three new ones. Tilda Swinton--a longtime Jarman friend and collaborator who many cite as being his muse--shares her thoughts on Jarman and the film. "He was very interested in how the individual survives any environment and the loneliness that any enclosed environment can instill," she says, adding that there was a feeling of family--and abandon--on the set. "There aren't that many artists working as filmmakers, and the thing about Derek which is really interesting is that he managed to come form a constituency of filmmaking--which is a fine-art constituency, generally speaking underground, and certainly experimental--and he managed to by two means...working with 35 millimeter early on, and secondly by the force of his own personality and his sense of himself as a performer. He crossed over into somewhere else."

Leading the way is a collection of four video interviews (30:22), led by three new ones. Tilda Swinton--a longtime Jarman friend and collaborator who many cite as being his muse--shares her thoughts on Jarman and the film. "He was very interested in how the individual survives any environment and the loneliness that any enclosed environment can instill," she says, adding that there was a feeling of family--and abandon--on the set. "There aren't that many artists working as filmmakers, and the thing about Derek which is really interesting is that he managed to come form a constituency of filmmaking--which is a fine-art constituency, generally speaking underground, and certainly experimental--and he managed to by two means...working with 35 millimeter early on, and secondly by the force of his own personality and his sense of himself as a performer. He crossed over into somewhere else."

Actor Nigel Terry reinforces Jarman's mantra to have a good time--sets were filled with laughter. Terry notes Jarman was a true Renaissance man: a painter, a filmmaker, a writer, a gardener...the list goes on. "He was sort of blasphemous, but he was kind, so he cared about people," Terry says. "(He was) not politically correct at all. He didn't follow a party line, he didn't follow a religious line. He saw the world for what it was--what he saw of it--a bit like Caravaggio. I think he liked Caravaggio because of that."

Actor Nigel Terry reinforces Jarman's mantra to have a good time--sets were filled with laughter. Terry notes Jarman was a true Renaissance man: a painter, a filmmaker, a writer, a gardener...the list goes on. "He was sort of blasphemous, but he was kind, so he cared about people," Terry says. "(He was) not politically correct at all. He didn't follow a party line, he didn't follow a religious line. He saw the world for what it was--what he saw of it--a bit like Caravaggio. I think he liked Caravaggio because of that."

Production designer Christopher Hobbs notes that the film was created as "Italy of the mind and memory", a blending of history and modern recollection that intentionally had lapses in period. He shares how he refined his storyboards over the years, and that the sets were made with "ingenuity and a lot of hard work." He adds with a laugh that "Derek hatred period movies, and he hated period costumes...be he kept on doing it."

The last video interview (in lower quality video) is an excerpt of Jarman speaking with Simon Field in a 1989 interview. He shares his fascination with Caravaggio's work--the cinematic style of his paintings, his rebellious nature, his sexuality ("Caravaggio's age was in many ways more open than ours was")--and notes that he also made the film as a statement against the American commercial culture that took over after World War II. "In a sense, this was my own throwing down the gauntlet at the American-oriented cinema, and saying, here is a film oriented toward Europe, which has always been the way I've worked." He also talks about his roots in underground/alternative/experimental cinema. All of the interviews provide a powerful look at the man and his mind.

The last video interview (in lower quality video) is an excerpt of Jarman speaking with Simon Field in a 1989 interview. He shares his fascination with Caravaggio's work--the cinematic style of his paintings, his rebellious nature, his sexuality ("Caravaggio's age was in many ways more open than ours was")--and notes that he also made the film as a statement against the American commercial culture that took over after World War II. "In a sense, this was my own throwing down the gauntlet at the American-oriented cinema, and saying, here is a film oriented toward Europe, which has always been the way I've worked." He also talks about his roots in underground/alternative/experimental cinema. All of the interviews provide a powerful look at the man and his mind.

Jarman is also represented in an audio interview (58 minutes) with Derek Malcolm at London's National Film Theatre after a preview screening of Caravaggio during the week leading up to its 1986 U.K. theatrical release. The audio is low quality, but is still easy to follow and provides more great material. Jarman expands upon his influences and his filmmaking process. Malcolm notes that the director has been called "the James Dean of the Italian Baroque"--an apt description--and says the film is vital because "there's a need for cinema that shakes hands with people without pissing on them." As for the "alternative" tag that Jarman lived with? "No," he replies. "I'm always the center."

Up next is a feature-length audio commentary with cinematographer Gabriel Beristain. It's an enthusiastic track (there are periods in the film where he stays quiet), and it's clear from the start he's a huge fan of the film--and Jarman: "It was the greatest experience of my whole entire life," he says, calling the film an incredible masterpiece. "Derek Jarman has been the best director and artist that I have ever worked for." Beristain spends a lot of time talking about the various lighting and camerawork techniques, nothing how they used yellow makeup on the actors playing Caravaggio to separate them from the background. He notes they shot the film the same way Caravaggio's paintings evolved in his life, referencing a form of chiaroscuro that the artist popularized. He adds that Jarman wanted sparse sets with nothing superfluous, adding that he considers Jarman an artist, not a "technician that makes films"--movies gave him a way to express his dreams, emotions, ideology and needs.

Rounding out the package is a photo gallery of storyboard, notebook, production photo and design sketches, and the films British theatrical trailer.

Wittgenstein (1993)

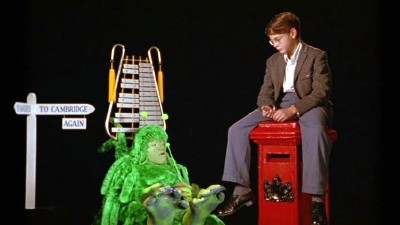

A philosopher who hated philosophy? What better subject for Derek Jarman to tackle than Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Austrian who pondered the connection between language and logic. Right from the start, you'll notice that Jarman is having some fun here: "If people did not sometimes do silly things, nothing intelligent would ever get done," notes young Ludwig (Clancy Chassay), staring directing into the camera to address us as he introduces his filthy rich family. "I'm a prodigy." All of the scenes are filmed as if this was a play, on a dark stage with minimal props and no sets.

Soon, Ludwig is waxing philosophical by a mail box with a Martian, who asks "How many toes do philosophers have?" It's a lot to soak in and adjust to, but Jarman still sticks with a somewhat linear narrative as young and old Ludwig (Karl Johnson) share their life--from childhood to Cambridge, from Norway to war, from Russia to death. Each sequence revels in minimalism. Everything is stripped down, forcing you to try and focus on the words and logic (which can sometimes be difficult).

The film is both frustrating and funny, much like we're led to believe the philosopher's mind was. The crux of his inner struggle comes as he tries to explore the limits of language after writing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus--a book that combines logical symbolism with religious mysticism. "It's what we do and who we are that gives meaning to our words," he says. "There are no genuine philosophical problems...philosophy is just a by-product of misunderstanding language."

Jarman frequently sidetracks us with humor. Ludwig prefers the cinema to seminars--he'd happily take in a Western or musical with Carmen Miranda or Betty Hutton over anything Aristotle has to offer. The director also links Wittgenstein's sexual identity struggle to his angst, and Johnson does a good job with tough material. Everyone else pitches in with memorable turns, especially Michael Gough as fellow philosopher Bertrand Russell and Tilda Swinton as Lady Ottoline Morrell, an English aristocrat and one of Russell's lovers ("That's the trouble with your Bertie," says Morrell. "You can never answer a straight question!").

John Quentin also gets solid screen time as British economist John Maynard Keynes, a lecturer at Cambridge who challenges Wittgenstein by the throwing the philosopher's own words back at him: "All aristocrats idealize the common folk, as long as they keep stoking the boilers." It's one of the many confrontations that frustrate Wittgenstein, whose struggle for perfection becomes his Achilles' heel.

This is a colorful film with bold images and statements, and is probably best enjoyed if you don't take it too seriously. If you're a philosophy novice (like me), just put yourself into the shoes of the other characters (the ones who challenge Wittgenstein, like many of his students). I loved the images Jarman created, and the film's playfulness trumps any confusion you might have with the cerebral gobbledygook. This is a must for Jarman fans, but others are best advised to start elsewhere with his work and ease into this one.

This is a colorful film with bold images and statements, and is probably best enjoyed if you don't take it too seriously. If you're a philosophy novice (like me), just put yourself into the shoes of the other characters (the ones who challenge Wittgenstein, like many of his students). I loved the images Jarman created, and the film's playfulness trumps any confusion you might have with the cerebral gobbledygook. This is a must for Jarman fans, but others are best advised to start elsewhere with his work and ease into this one.

Transfer:

Presented in a restored, 1.66:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer from high-definition elements, Wittgenstein is another solid effort. The film is a study in contrasts, with the black background repeatedly broken with colorful props and costumes. The 2.0 surround sound (with optional English subtitles) is more than adequate--there's very little use of intense audio here. This is more about dialogue, with the subtle sound effects serving their purpose.

Extras:

Leading the way is an introduction (4:24) by film historian Ian Christie, a former philosopher. He talks about the importance of the film (which he notes "re-animates the clichés of the costume drama"), and addresses some of the controversy it created.

Up next is a collection of three short but heartfelt video interviews (28:32), once again led by Swinton. The footage was shot during the same interview she gave in the extras of Caravaggio, and you'll notice that a few minutes of her 10-minute clip here were also included on that release. She spends more time talking about Jarman than the film, and reflects on his nature: "In his enthusiasm for adventure, he was genuinely child-like. He was never disillusioned, and very rarely dispirited," she says. "He had an extraordinary charisma. He was a drama queen, and he was so delightful with it." She also addresses his filmmaking strategy ("it was all about process") and his two camps of film: "Derek Jarman Red Label and Derek Jarman-lite," with the choice of 35mm or Super 8 influencing his creative process.

Up next is a collection of three short but heartfelt video interviews (28:32), once again led by Swinton. The footage was shot during the same interview she gave in the extras of Caravaggio, and you'll notice that a few minutes of her 10-minute clip here were also included on that release. She spends more time talking about Jarman than the film, and reflects on his nature: "In his enthusiasm for adventure, he was genuinely child-like. He was never disillusioned, and very rarely dispirited," she says. "He had an extraordinary charisma. He was a drama queen, and he was so delightful with it." She also addresses his filmmaking strategy ("it was all about process") and his two camps of film: "Derek Jarman Red Label and Derek Jarman-lite," with the choice of 35mm or Super 8 influencing his creative process.

Karl Johnson then shares his thoughts on making the film, noting with refreshing honesty that he had trouble making sense of it all: "It was hard to learn, trying to figure out some of it out, which was stupid because...you can't!" He also shares his thoughts on Jarman, a man who was "as enthusiastic talking about a feather boa as he was about the Tractatus. That's what I liked about him...he didn't seek approval." Closing the interviews is producer Tariq Ali, who talks about the funding and filming of Wittgenstein, and about Jarman--who embraced low budgets because it forced everyone to be more creative. The funniest moment comes when he recalls how he told Jarman that he needed to shock his fans with this work. When the director asked how, Ali answered: "No bums and willies at all. That will shock them!"

Karl Johnson then shares his thoughts on making the film, noting with refreshing honesty that he had trouble making sense of it all: "It was hard to learn, trying to figure out some of it out, which was stupid because...you can't!" He also shares his thoughts on Jarman, a man who was "as enthusiastic talking about a feather boa as he was about the Tractatus. That's what I liked about him...he didn't seek approval." Closing the interviews is producer Tariq Ali, who talks about the funding and filming of Wittgenstein, and about Jarman--who embraced low budgets because it forced everyone to be more creative. The funniest moment comes when he recalls how he told Jarman that he needed to shock his fans with this work. When the director asked how, Ali answered: "No bums and willies at all. That will shock them!"

You also get a collection of behind-the-scenes footage (24:56) from the film, broken into seven sections. There's no narration and no talking to the camera--it's just raw footage of Jarman at work, and is a testament to his fun, laid-back style. It's clear that he embraced everyone on the set, fostering a real sense of family. It's fun to watch him and Tilda ponder over how to eat chocolate as she reads a letter, and to see Jarman enthusiastically direct an equally colorful trio of actors. Rounding out the features is "The Clearing", a short film (5:00) from Alexis Bistikas that has Jarman in a small role.

You also get a collection of behind-the-scenes footage (24:56) from the film, broken into seven sections. There's no narration and no talking to the camera--it's just raw footage of Jarman at work, and is a testament to his fun, laid-back style. It's clear that he embraced everyone on the set, fostering a real sense of family. It's fun to watch him and Tilda ponder over how to eat chocolate as she reads a letter, and to see Jarman enthusiastically direct an equally colorful trio of actors. Rounding out the features is "The Clearing", a short film (5:00) from Alexis Bistikas that has Jarman in a small role.

The Angelic Conversation (1985)

"Being your slave, what should I do but tend upon the hours and times of your desire..."

Long cited by Jarman as his favorite work, this film is one of his most experimental efforts. Shot on Super 8 (and blown up to 35mm), it has Judi Dench narrating 14 of Shakespeare's sonnets as images slowly unfold on the screen. Paul Reynolds and Phillip Williamson are the subjects, and Jarman gives a homoerotic interpretation of the sonnets. Dench reads a few lines, then fades away for a while as the imagery and sound take over.

Long cited by Jarman as his favorite work, this film is one of his most experimental efforts. Shot on Super 8 (and blown up to 35mm), it has Judi Dench narrating 14 of Shakespeare's sonnets as images slowly unfold on the screen. Paul Reynolds and Phillip Williamson are the subjects, and Jarman gives a homoerotic interpretation of the sonnets. Dench reads a few lines, then fades away for a while as the imagery and sound take over.

The film explores themes of love, desire, heartache, longing and enslavement, and the music (an original composition by Coil) alternates between soothing, tender sounds and harsh, jarring ones. The audio uses other effects to help explore its themes, relying on the sound of water, birds, breathing, a clock, a fog horn, bees, bells and plenty of other cues to enhance the images, which frequently include fire, water and flowers.

The actors never speak, and there is no clear narrative--we see a man struggling with a load on his back, working his way up a hill; a man staring out a window, lost in thought; two men wrestling; a swimmer; a man kissing the body of his desire; two men sleeping; and many others. The images are mostly grainy, while Jarman employs a technique similar to stop-motion, slowing down the film in many sequences. He frequently employs a monochrome, black-and-white process, while other sequences have a more standard video look and are in color.

The actors never speak, and there is no clear narrative--we see a man struggling with a load on his back, working his way up a hill; a man staring out a window, lost in thought; two men wrestling; a swimmer; a man kissing the body of his desire; two men sleeping; and many others. The images are mostly grainy, while Jarman employs a technique similar to stop-motion, slowing down the film in many sequences. He frequently employs a monochrome, black-and-white process, while other sequences have a more standard video look and are in color.

For many viewers, this will be a challenging watch. I like the idea, but for me the images weren't strong enough to keep my interest for 75 minutes. It was powerful in spots, but it couldn't maintain that for extended periods.

"What eyes have put love in my head, which have no correspondence with true site. Or if they have, where has my judgment fled..."

Transfer:

Presented in a restored full-frame picture, I image this looks just about as good as it can given the source. There's plenty of grain, and no sharpness. There's a shift between black-and-white images with various tints, with some scenes in color. The 2.0 audio presentation (with optional English subtitles) is boisterous, which can sometimes be a problem when Dench is speaking...the sound fights for your attention, making it hard to smoothly understand some of the words she is saying. But the other audio effects Jarman throws at you are done well, helping create a mood of unease or serenity.

Presented in a restored full-frame picture, I image this looks just about as good as it can given the source. There's plenty of grain, and no sharpness. There's a shift between black-and-white images with various tints, with some scenes in color. The 2.0 audio presentation (with optional English subtitles) is boisterous, which can sometimes be a problem when Dench is speaking...the sound fights for your attention, making it hard to smoothly understand some of the words she is saying. But the other audio effects Jarman throws at you are done well, helping create a mood of unease or serenity.

Extras:

You get three video interviews (48 minutes), the best being Jarman. He's talks with Simon Field in a 1989 television show. This is the same interview that you saw a clip of in the Caravaggio extras--while that just used a sampling, this offers the full interview (32 minutes). Jarman talks about a wide range of things: how he got involved with film as a set designer for Ken Russell, how he started using Super 8, his filming/narrative choices and his role as a gay filmmaker and activist. "I'm a very traditional filmmaker, conservative with a small 'c'. I found that the times I lived in sort of marginalized the sort of ways that I thought, and sexuality as I experienced it," he says. "I've never made a film that I didn't think was sort of conservative. I never actually thought of my films as being radical."

You get three video interviews (48 minutes), the best being Jarman. He's talks with Simon Field in a 1989 television show. This is the same interview that you saw a clip of in the Caravaggio extras--while that just used a sampling, this offers the full interview (32 minutes). Jarman talks about a wide range of things: how he got involved with film as a set designer for Ken Russell, how he started using Super 8, his filming/narrative choices and his role as a gay filmmaker and activist. "I'm a very traditional filmmaker, conservative with a small 'c'. I found that the times I lived in sort of marginalized the sort of ways that I thought, and sexuality as I experienced it," he says. "I've never made a film that I didn't think was sort of conservative. I never actually thought of my films as being radical."

Production designer Christopher Hobbs (in interview footage shot at the same time as his Caravaggio interview) notes that Jarman relished in experimenting with technology, and this film was a subconscious diary with fragments of memory, thoughts and glimpses of ideas that he had filmed over the years. "I'm not sure there was a great deal of philosophical thought behind them, like a lot of conceptual art--which it was. It was very much out of the '60s and '70s, this sort of conceptual, multiple, communal art idea, and then you put a title on afterwards and sort of justify what you'd done by calling it something. But it didn't actually start out...with a very strong idea."

Production designer Christopher Hobbs (in interview footage shot at the same time as his Caravaggio interview) notes that Jarman relished in experimenting with technology, and this film was a subconscious diary with fragments of memory, thoughts and glimpses of ideas that he had filmed over the years. "I'm not sure there was a great deal of philosophical thought behind them, like a lot of conceptual art--which it was. It was very much out of the '60s and '70s, this sort of conceptual, multiple, communal art idea, and then you put a title on afterwards and sort of justify what you'd done by calling it something. But it didn't actually start out...with a very strong idea."

Producer James Mackay is also interviewed, and says that "Derek's films were essentially about Derek...they are all films where Derek is the essential character." He shares how Jarman re-filmed his Super 8 material onto video by projecting it onto a wall and capturing in using a VHS porta pack, and notes that the film grew on one hand as the soundtrack grew on another. Mackay adds that The Angelic Conversation was created out of different ideas that melded together. Mackay notes that this was Jarman's favorite work: "It was very gentle and fairly direct as a film...and it was a beautiful summer. He had a great time."

Producer James Mackay is also interviewed, and says that "Derek's films were essentially about Derek...they are all films where Derek is the essential character." He shares how Jarman re-filmed his Super 8 material onto video by projecting it onto a wall and capturing in using a VHS porta pack, and notes that the film grew on one hand as the soundtrack grew on another. Mackay adds that The Angelic Conversation was created out of different ideas that melded together. Mackay notes that this was Jarman's favorite work: "It was very gentle and fairly direct as a film...and it was a beautiful summer. He had a great time."

Blue (1993)

By the time Jarman was filming Wittgenstein, he was already starting to go blind as a result of complications from the AIDS virus. That ended up being his final "traditional" work with actors, but Blue is his last film. Like The Angelic Conversation, it's a more avant-garde entry that may be hard for many people to enjoy. If you're in the mood for reflection, it can be quite powerful. The film is like an audio diary with thoughts, life stories, dreams and music all being shared as a blue screen--with no other visuals--fills the canvas for 75 minutes.

By the time Jarman was filming Wittgenstein, he was already starting to go blind as a result of complications from the AIDS virus. That ended up being his final "traditional" work with actors, but Blue is his last film. Like The Angelic Conversation, it's a more avant-garde entry that may be hard for many people to enjoy. If you're in the mood for reflection, it can be quite powerful. The film is like an audio diary with thoughts, life stories, dreams and music all being shared as a blue screen--with no other visuals--fills the canvas for 75 minutes.

The film is narrated by four voices, with Jarman joined by Nigel Terry, John Quentin and (briefly) Tilda Swinton. All of them speak as Jarman, who alternates childhood stories with musings on life, love and sexual roles. Those segments are interspersed with his current struggle, as he shares his thoughts on losing his sight and dealing with the complications from DHPG drug treatment, feeling further defeated as his body betrays him. "All that concerns either life or death is all transacting and at work within me now," we hear early on, as the narrator ponders the importance of current global warfare news. "If I lose half my sight, will my vision be halved?" he later asks. "I resign myself to fate...blind fate."

Jarman seems to be challenging us to see what he sees--or at least how he sees--using sounds and words to force us to create our own visuals and meaning. The color becomes a symbol for everything: life, love, death, bliss, cold, sound...and also represents a slipping away as he eyes heaven. In the bonus features for The Angelic Conversation, producer James Mackay says: "With Blue, he said, 'I finally have done what I always had to do surreptitiously...that is, make a film about myself. In the other films, I had to disguise myself as Caravaggio" and all of his other subjects.

Jarman seems to be challenging us to see what he sees--or at least how he sees--using sounds and words to force us to create our own visuals and meaning. The color becomes a symbol for everything: life, love, death, bliss, cold, sound...and also represents a slipping away as he eyes heaven. In the bonus features for The Angelic Conversation, producer James Mackay says: "With Blue, he said, 'I finally have done what I always had to do surreptitiously...that is, make a film about myself. In the other films, I had to disguise myself as Caravaggio" and all of his other subjects.

Jarman also adds sound effects to help paint a picture, whether it's a cold wind, the waves of the ocean, a ticking clock, a thunderstorm, a busy café, bells, all of it joined by music of changing moods. The most haunting audio comes from the hospital sequences, with a breathing machine and other cold, sterile sounds forcing us to think about facing death. "I'm walking along the beach in a howling gale...another year is passing. In the roaring waters I hear the voices of dead friends...love is life...it lasts forever," he says, soon reciting a list of lovers, whose names echo through the film: Dave, Howard, Graham, Terry and Paul (Blue is dedicated to the frequently referenced H.B. and "All True Lovers").

This is a thought-provoking, haunting and powerful work that stands as Jarman's final piece of art, a legacy of life created as he eyed death. It's certainly not for casual viewers, and I'm guessing a majority of film fans will find it too frustrating a sit (I did prefer this to The Angelic Conversation). This is best left to Jarman enthusiasts, and anyone open to exploring its many themes free of forced visuals.

Transfer:

Presented in a new, anamorphic 1.85:1 transfer, this is just a blue screen--no change in shade, so it really doesn't matter how it looks, right? Some black and white film specs pop on the canvas every so often. The 2.0 surround track (with optional English subtitles) is solid, with all of the narration, sound effects and music being robust.

Extras:

The sole extra presented here is the film Glitterbug, a heartfelt collage of various Super 8 home movies and video from Jarman's library. Posthumously assembled with love by his friends in 1994, it is set to an original (and sometimes jarring) score from Brian Eno (there's no narration). The full-frame presentation varies in quality with each sequence (most of it looks rough), and features a wide range of subjects. Jarman is frequently in front of the camera (he films himself shaving and sleeping), along with the warm smiles of many friends. There's a fashion show, an outdoor gathering, behind-the-scenes footage from his 1976 film Sebastiane, various shots of nature and art, shots of his neighborhood and friends just relaxing. It's a fitting complement to Blue, with no words forcing us to focus on Jarman's vision as he shows us what caught his eye during his life. We can only wonder what unique and wonderful stories belong to each person and shot, what intent came with each sequence...and I'm guessing that's exactly what Jarman would have wanted.

The sole extra presented here is the film Glitterbug, a heartfelt collage of various Super 8 home movies and video from Jarman's library. Posthumously assembled with love by his friends in 1994, it is set to an original (and sometimes jarring) score from Brian Eno (there's no narration). The full-frame presentation varies in quality with each sequence (most of it looks rough), and features a wide range of subjects. Jarman is frequently in front of the camera (he films himself shaving and sleeping), along with the warm smiles of many friends. There's a fashion show, an outdoor gathering, behind-the-scenes footage from his 1976 film Sebastiane, various shots of nature and art, shots of his neighborhood and friends just relaxing. It's a fitting complement to Blue, with no words forcing us to focus on Jarman's vision as he shows us what caught his eye during his life. We can only wonder what unique and wonderful stories belong to each person and shot, what intent came with each sequence...and I'm guessing that's exactly what Jarman would have wanted.

For a great read on Jarman and other great GLBT cinema content, check out Jim's page from jclarkmedia.com. He can provide a lot more insight into Jarman and his work than me!

The PACKAGING:

The four discs are housed in a paper-quad fold with a paper slipcase. An 18-page booklet is included, featuring brief and enlightening essays on the man and his work, as well as a short Q&A with Oscar winning costume designer Sandy Powell, whose first feature as a designer was Caravaggio. Her standout work has been featured in great films like The Aviator, Far From Heaven and Shakespeare in Love, among many others.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

For Jarman enthusiasts, fans of experimental films or those into alternative gay cinema, this is an essential collection. For those new to his work, it's probably best to rent a few titles first. Caravaggio is the most "mainstream" entry here, a beautiful work with smoldering performances that have stood the test of time--it comes highly recommended. The other entries stray off the path a little bit, and offer a thought-provoking, challenging, passionate--and sometimes frustrating--viewing experience. If you know what you're getting yourself into and are open to the experience, this is a great introduction to a unique filmmaker. With four films new to DVD and a fantastic batch of extras compiled with love, Glitterbox not only shows Jarman's love for art and film, but it also shows the love he inspired in others. Recommended, but not for everyone.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||