| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Western Classics Collection (Escape from Fort Bravo/The Law and Jake Wade/Saddle the Wind/Cimarron/The Stalking Moon)

This is a no-frills set; there are no commentaries, no behind-the-scenes documentaries, just the movies and trailers for most of them, but the transfers are good and there are a few surprises. One film especially is an unsung classic of the genre.

John Douglas Eames, author of The MGM Story describes Escape from Fort Bravo as "a rousing tale of North versus South and Indians versus everybody," an apt description. Set in Arizona Territory during the Civil War, at a POW camp for Confederate soldiers, the film stars William Holden as embittered, hardened Captain Roper, who at the beginning of the film has brought back escaped prisoner Bill Bailey (John Lupton), ruthlessly dragging him for miles when the man ran his horse to death trying to flee.

As Roper and his C.O. (Carl Benton Reid) debate whether to supply guns to the prisoners should the Mescalero Apaches attack the fort, tensions are relieved somewhat by the appearance of beautiful Carla Forester (Eleanor Parker), at the fort for the wedding of Alice Owens (Polly Bergen) to Lt. Beecher (Richard Anderson). Carla and Roper tentatively embark on a romance, she mainly trying to reach the reticent captain. He begins to let his guard down a little, and it's revealed early that in fact she's the lover of Reb Captain John Marsh (John Forsythe), and the key to an escape plan also involving Confederate soldiers Bailey, Campbell (William Demarest) and Young (William Campbell).

Based on a story co-written by the late character actor Michael Pate (who died earlier this month), Escape from Fort Bravo was directed by John Sturges (Bad Day at Black Rock, The Magnificent Seven) and plays to his strengths at helming outdoor action. The location footage, much of it shot in Death Valley, is highly suspenseful and exciting though the film is undermined by unusually phony-looking studio exteriors and too much intrusive romance leading nowhere.

The best scenes are the lead-up to an Indian attack early in the film and the climatic cat-and-mouse game between the principals and Mescalero near the end. Unusual for an MGM film of that time, Sturges really reigned in the underscoring. Soldiers on horseback nervously traverse a narrow canyon as Indians close in from above. There's no music or dialogue, just the sound of the horses' hoofs on the gravelly path. Late in the film the main characters are pinned down in the open desert, and in a scene unlike any I can recall in a Western the Indians use mathematics to aim and fire scads of arrows at once, like artillery. (This scene too has little-to-no music.) It's very logical and ingenious how the Indians close in, and the growing fear and realization of what's happening to the heroes is realistic and nail-biting.

Conversely, the audience never really gets to know how Holden's character came to be such a dark, cynical character. Though the actor is very good in the scenes with Parker they don't really add up to anything; that the third point in this love triangle is a Confederate soldier in the end means nothing, and Forsythe's character is almost minor, of less importance and interest than either Campbell and Demarest, fun as a bickering hothead and grizzled old-timer.

The film is interesting for other reasons. It incorporates elements that turn up in later Sturges films such as The Great Escape (1963, and like that film, Escape from Fort Bravo has a "curtain call" for the cast); and the Confederate prisoners defiantly whistle "Dixie" to their captors, a device Sam Peckinpah revisited in Major Dundee (1965).

The Law and Jake Wade is a simple reworking of Escape from Fort Bravo, much less satisfying the second time around. Instead of soldiers on opposite sides of the Civil War battling Indians it's former outlaw-turned-U.S. Marshal Jake Wade (Robert Taylor) and his fiancée, Peggy (Patricia Owens of Sayonara and The Fly fame) on one side, with ruthless murderer Clint Hollister (Richard Widmark) and his bunch on the other, all of whom must contend with a big Indian attack near the climax.

The story, a reworking of a Western staple, opens with Jake breaking Clint out of jail, to settle an old debt, because Clint once did the same for Jake. But Clint isn't ready to call things even: he wants the $20,000 they robbed from a bank years before, which Jake buried and forsook after a young boy was killed in Jake's crossfire.

Jake refuses to reveal the location of the hidden loot, but then Clint kidnaps and threatens to kill Peggy, so once again the reformed outlaw is forced to ride with Clint and the old gang: Ortero (Robert Middleton), Wexler (DeForest Kelley), and Burke (Eddie Firestone), as well as newcomer Rennie (Henry Silva).

The Law and Jake Wade is okay, but it's less innovative than Escape from Fort Bravo, though as with the earlier film director Sturges makes great use of the film's locations, shot here by Robert Surtees. The last quarter of the film takes place in an authentic-looking ghost town, and the staging of the climatic battle with the Indians is lively.

Personally, I've always found Robert Taylor one of the least interesting stars of the Classical Hollywood period, and his ultra-right wing views, including support of racial segregation and the blacklist, to be an added turn-off. He's pretty ridiculous in something like Quo Vadis (1951), but as an older leading man in '50s and '60s Westerns he's not bad as a world-weary hero.

Taylor was probably naturally uncomfortable around co-star Richard Widmark, a left-leaning actor still at the time trying to shake his psychotic killer image after Kiss of Death a decade before. He's also not bad, though one gets the sense, as was often the case when Widmark played these kinds of roles, that he conveys an intelligence at odds with the simplistic character he's playing.

In an early role, Henry Silva, who played even more psychos than Widmark, comes off best as the young rider in Widmark's gang, a man raised by an abusive preacher-charlatan he eventually murdered. Silva played innumerable characters like this in his long career, but never quite like this: he's very relaxed and cocky, very New York attitude with slight Brooklynese accent (something never discussed in the film), and casually sadistic. It's a fascinatingly off-kilter characterization, subtly unlike any I've seen before.

Many Rivers to Cross is easily dismissed as a kind of non-musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers taken on the road with a second-rate cast. It's one Robert Taylor movie too many, qualifies as a Western more by strict definition than in terms of audience expectations, and is pretty charmless. I wish they had chosen something else.

In late 18th century Kentucky, trapper Bushrod Gentry (Taylor; his character sounds like the name of a punk band) is wounded in a skirmish with Shawnee Indians (in fake mohawk baldcaps) and rescued by sharp-shooting pioneer woman Mary Stuart (Eleanor Parker), an Annie-Oakley type. She takes Bushrod back to her large family, including parents Cadmus and Ma Cherne (Victor McLaglen and Josephine Hutchinson), and their unmarried sons: Fremont (Jeff Richards), Shields (Russ Tamblyn), Hugh (John Hudson), and Banks (Russell Johnson). Mary Stuart's also got a boorish, brutish suitor in Luke Radford (Alan Hale, Jr.) but she's got no use for him; she's already set on lassoing manly Bushrod.

Mostly shot on what looks like redressed sets left-over from Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (Russ Tamblyn must have felt a bit of déjà vu), Many Rivers to Cross is rowdy and broadly-played but not very funny and the CinemaScope adventure aspects are pretty lackluster. Taylor and Parker aren't right for the material, actors like Tamblyn and Johnson are underutilized, McLaglen and his brogue are cloyingly cute, while poor Alan Hale is just flat-out awful in a badly-written, clichéd part. (One does get a chance to see The Skipper and The Professor in the same scenes, however.)

Saddle the Wind is an odd one, featuring as it does a screenplay by Rod Serling, then at the peak of his prestige as a writer for television, and because of its strange combo of talent in the leading roles: old guard Hollywood heavyweight and right-winger Robert Taylor; smoky-voiced lounge singer Julie London; and liberal New York method actor John Cassavetes.

The film opens promisingly, with gunfighter Larry Venables (Charles McGraw) slowly riding into town under the main titles, over which feature a haunting, lullaby-type title song performed by London. But the film goes downhill real fast into overly familiar territory that's both pretentious and badly directed (by Robert Parrish).

It's the old, old story of the reformed older gunfighter-turned-cattleman, Steve Sinclair (Robert Taylor), and his cocky, impetuous kid brother, Tony (Cassavetes), who overcompensates for feelings of inadequacy and jealously by becoming a fast-draw bully. At first it looks like maybe Tony's fiancée, saloon girl Joan Blake (London) might be able to tame him, but once farmer Clay Ellsion (Royal Dano) and his clan threaten to wire off the open range Tony goes ballistic, even after local rancher / patriarchal figure Dennis Deneen (Donald Crisp) guarantees the farmers' protection. An inevitable Cain and Abel showdown looms in the horizon.

As great a television writer Rod Serling was, his feature film screenplays were problematic at best and usually quite mediocre. In Saddle the Wind there's too much talking and not enough showing; it's an incredibly static, lifeless film made even worse by an over-reliance on cutting between real exteriors and medium- and close-shots of actors standing in front of rear screen projections and painted backdrops, all of which appear incredibly phony and artificial. The cutting is also frequently awkward and distracting, as if the film was heavily retooled in postproduction.

The other big problem is that Tony is obviously nuts from the earliest scenes and completely reprehensible and unsympathetic the rest of the time. The end of the film wants us to feel sorry for Taylor's character, having to hunt his own brother down like a mad dog, but Tony's had it coming for some time. London's character is introduced only to be tossed off to the sidelines during the second-half; there's not even the hint that she'll wind up in the arms of Taylor's character, the obvious way for these things to go. Serling probably thought he was being clever resolving the final gunfight between the two brothers the way he does, but instead of being startlingly original it merely plays like a colossal cop-out.

You know something's wrong when Robert Taylor gives the film's best performance, though Donald Crisp is quite good as the stern but eminently fair cattleman, and his character's actions livens things up a bit during the superior second-half. Cassavetes is really indulgent with the Method playing, making no attempt to stylistically blend in with the other actors, even seasoned character players like Crisp and Douglas Spencer (as Taylor's foreman). London is pretty but with her very '50s makeup and hairstyle, to say nothing of her very usual features (slightly wall-eyed, overbite) she's never anything but totally out of place.

A sprawling epic Western strangely forgotten today, despite its pedigree as an adaptation of an Edna Ferber (Giant) novel, an all-star cast, and direction by Anthony Mann - one of the Western genre's great talents - Cimarron for the most part is quite good, innovative even, despite some studio-imposed compromises.

The picture opens days before the mad land rush at the Oklahoma territorial border on April 22, 1889, where hundreds of thousands of hopeful settlers hope to secure one of the 12,000 or so parcels of free land. Among them are newlyweds Yancey Cravat (Glenn Ford) and his wife, Sabra (Maria Schell); prostitute - and Yancey's former lover - Dixie Lee (Anne Baxter); newspaper publishers Sam and Mavis Pegler (Robert Keith and Aline MacMahon); Jewish merchant Sol Levy (David Opatoshu); poor farmer Tom Wyatt (Arthur O' Connell) and his wife (Mercedes McCambridge) and their large brood of daughters; and cocky, budding gunfighters "The Cherokee Kid" (Russ Tamblyn) and Wes Jennings (Vic Morrow).

When Yancey loses his prized land to Dixie and publisher Sam is trampled to death during the mad rush of horses, buckboards and stagecoaches, Yancey agrees to take over the Oklahoma Wigwam in the fictitious town of Osage instead.

Though the paper does well enough, Yancey is a man of such stubborn principles as to be frequently impractical and inconsiderate of his family's basic security and safety. He's also an inveterate rambler, a man with chronic wanderlust. Constantly in search of adventure (such as joining Teddy Roosevelt's Roughriders) he abandons his family for years at a time. Sabra, left to raise their son and care for a widowed Indian and her daughter, who Yancey adopted, grows increasingly resentful of her irresponsible husband. As others around her become obscenely rich (Tom Wyatt, for instance, becomes an oil baron), she struggles just to keep the family newspaper afloat.

Though a bit embarrassed to admit I've never seen the supposedly superior, 1931 film version of Cimarron, Mann's 1960 film is interesting in many respects. For one thing Yancey and Sabra are intriguingly ambiguous characters, neither entirely sympathetic. Yancey is the sort of nation-building pioneer who helped tame the West, a dreamer and visionary, but he's also selfish and compulsively irresponsible. (Mild Spoiler) He basically absent for the entire last half-hour of the film; nobody even knows where he is, and he doesn't return for a teary-eyed reunion/fade-out, either. Sabra loves him and puts up with his wanderlust to a point; at first she seems to be the selfish one, overly cautious and standing in the way of progress, fearful and suspicious of Indian strangers Yancey risks his life protecting.

Like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the film questions who really tamed and civilized the West. Was it adventure-seekers like Yancey or those thanklessly holding down the fort like Sabra? Schell's "smiles under the tears" performance is perfectly suited here; she goes way, way, beyond the long-suffering pioneer wife, pulling a far richer and more complex characterization that makes a lasting impression. Ford is a bit too mumbling; in early scenes you wonder if the role hadn't been intended for Jimmy Stewart. But when their characters' marriage deteriorates, Ford's up to her level performance-wise, and they make a memorable screen couple.

Civilization-building Westerns were popular in the 1920s during America's pre-Depression metropolis-building boom, but much less so in the decades after. It's fascinating to watch this film's town literally metamorphose from an empty plain to a bustling city over the course of two hours, and to follow the ups and downs of its ensemble cast. MGM reportedly cut back on the budget to the point where a lot of location shooting was moved onto big soundstages with painted cycloramic backdrops. This cost-consciousness is apparent, but it doesn't damage the film the way the overuse of process shots hurts Saddle the Wind. (There's some great footage of the MGM backlot in the opening scenes.)

And despite the overuse of studio-bound "exteriors," the location footage is gorgeously photographed by Robert Surtees; I particularly like the way he shoots panoramic shots involving dark, overcast skies.

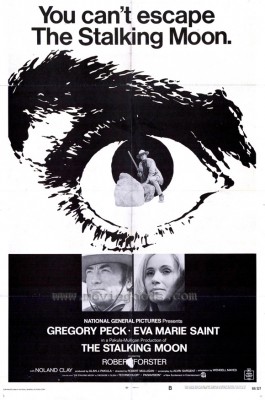

I had only vaguely heard of The Stalking Moon, most of it negative, but it's really one of the unsung classics of the genre; obviously it was lost in the jumble of great, innovative and/or popular Westerns that came out of the late-1960s (The Wild Bunch, True Grit, etc.) and may been too subtle and adult for the John Wayne crowd; many pegged the film as arty and pretentious, but it's neither of those things.

It's the kind of film best experienced with no knowledge of where things are heading going in, so if you're planning on watching this for the first time soon, you'd better stop reading this review.

Sam Varner (Gregory Peck) is a newly retired Army scout getting ready to quietly start a small farm in New Mexico territory. For part of the way he reluctantly agrees to escort Sarah (Eva Marie Saint), a newly-rescued former Apache captive held prisoner for ten years, along with her half-breed son. But something isn't right, and fairly soon it becomes clear that the Indian who fathered the boy wants him back, and nothing is going to stand in his way.

The film becomes an incredibly suspenseful, almost unbearable by the end, game of cat-and-mouse; the entire second-half of the picture has Sam, Sarah, the boy, an old handyman (Russell Thorson), and Sam's half-breed Army partner, Nick Tana (Robert Foster), holed up in Sam's log cabin as the determined Indian patiently waits them out, preparing to strike when they least suspect it. (The set-up is a lot like The Thing (From Another World); one half expects the Indian to be on the other side of a casually opened door.)

Peck is his usual towering presence, and both he and Saint give remarkable performances with a minimum of dialogue. (Saint probably says no more than 50 words during the entire picture, partly because he character hasn't used English in so long she has difficulty verbalizing her thoughts.) Peck especially is wonderful, conveying a wide range of emotion from his reluctance to help Sarah and the boy early on, to a mind racing to outguess his opponent's next moves with few options open to him.

Equally fine is an almost unrecognizable Robert Forster as Peck's uneducated but very intelligent and highly-skilled Indian companion. It's a stock Western genre character, but Forster makes it uniquely his own. All three give Oscar-worthy performances. Another fine actor in a small role as a cavalry officer at the beginning is James Olson, curiously both unbilled and (apparently) dubbed by another actor.

This is an exceptionally good adult Western, methodical and very logical both in terms of the characters' psychology and the authenticity of the skills that are depicted (Sam's abilities as a tracker, for instance). If you don't want the whole set, this is the film to buy individually.

Video & Audio

All six titles are 16:9 enhanced widescreen. The IMDb lists Escape from Fort Bravo as 1.37:1 but that's incorrect, and the 1.78:1 framing here looks about right. (Most American film companies adopted 1.85:1 as their non-'scope widescreen standard by 1954, but for some reason both MGM and Disney preferred 1.75:1 for their productions, at least for the next 15 years or so.) Escape from Fort Bravo was filmed in the unfortunate Ansco Color process, the American version of Agfacolor. MGM used it extensively in the mid-1950s, and almost all of those movies look terrible today. In this case, the film is grainy and even downright blurry at times, and the color pallet really seems to favor ugly reds and browns. Conversely, the film includes an unexpectedly strong Dolby Stereo Surround mix - it was made when many early 3-D and widescreen films had mag-stereo tracks (interlocked or on the film) - with fully directional dialogue and sound effects.

The Law and Jake Wade, filmed in CinemaScope, seems overly dark though perhaps Sturges and Surtees were trying to evoke a noirish atmosphere, as many shots have the characters in silhouette, opaque or nearly so against desolate backgrounds. But it is hard to tell the (poor) day-for-night footage from the day-for-day scenes. The Metrocolor is a step up from Fort Bravo's garish Ansco hues, but the audio is a disappointment. Though released in Perspecta Stereophonic Sound, the DVD is mono only on both this and Saddle the Wind; the Perspecta tracks have not been decoded for this release.

Similarly, Many Rivers to Cross almost certainly was released theatrically in four-track magnetic stereo, but this release is likewise mono. The Eastman Color production comes with all the problems inherent in those earliest CinemaScope lenses, but the color is good and the image otherwise fine.

Cimarron was shot with much-superior Panavision lenses and looks spectacular, with even more impressive Dolby Surround Stereo with fully directional dialogue and sound effects, and which adds enormous oomph to Franz Waxman's superb score. I don't know if this was ever shown with an Overture, Intermission, etc., but there's none of that here.

The Stalking Moon in Panavision with original prints by Technicolor, looks very good also; its mono audio is adequate. English and French subtitles accompany the features, which have chapter stops but no scene selection menus.

Extra Features

The only supplements are Trailers included with each title except for The Stalking Moon (a shame; I wonder how it was advertised in light of the strange poster). The Trailer for Escape from Fort Bravo is 4:3 standard size, the others are 4:3 letterboxed in varying condition.

Parting Thoughts

There are no Red Rivers or Winchester '73s or Searchers in Warner's Western Classics Collection, but for genre fans there's plenty to like, with several underrated films in the batch others will enjoy discovering. It's pricey but Recommended.

Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's latest book, The Toho Studios Story, is on sale now.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||