| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection (A Streetcar Named Desire, East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof)

Warner Home Video and Turner Classic Movies have released TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection: Romantic Dramas, a mouthful of a moniker that may not exactly apply to every film gathered here on these two flipper discs. Titles include Elia Kazan's A Streetcar Named Desire and East of Eden, Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause, and Richard Brooks' Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (is Streetcar really a "romantic" drama?). There's no need to double-dip if you already have the special editions of these titles; TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection: Romantic Dramas carries over some (but not all) of the extras from the two-disc special editions for Streetcar, Eden, and Rebel, while keeping all of Cat's special edition extras. Newcomers to the titles included on TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection: Romantic Dramas would be the discs' best fit; the titles gathered go together well, the transfers are quite good, and there are enough extras (at an affordable price) to make the set an attractive alternative to the more expensive individual special editions. Let's look very briefly at each title.

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE

"Western Union? Desperate circumstances! Caught in a trap!"

Arriving by train from the bucolic hinterlands of Louisiana, Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) descends into New Orleans' violent, overheated, oversexed French Quarter, looking for the aptly-named "Elysian Fields" townhouse where her sister, Stella Kowalski (Kim Hunter), now lives. Blanche, close to suffering a complete nervous breakdown after losing her position as a high school English teacher, has come to live with her sister because, in addition to her job, she has lost their ancestral home, Belle Reve. Stella, frightened at the obvious decline in Blanche's mental state, is nonetheless glad her sister has come to live with her - something that can't be said for her husband, brutish lout Stanley Kowalski (Marlon Brando). An unaffected plebeian with a hair-trigger b.s. meter, Stanley instantly sees through patrician Blanche's innumerable verbal dodges and evasions - survival tricks that hide a sordid, complicated past. Stanley's mama's boy friend, Mitch (Karl Malden), taken with the otherworldly Blanche, sees only the façade of gentility and coquettishness that the terrified, wounded woman hides behind, until Stanley finally uncovers her past, and commits a brutal act of betrayal that shatters all concerned.

SPOILERS ALERT!

An emotionally overwhelming experience even fifty-eight years after it debut shocked audiences and critics, Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire is that rare watershed film that continues to outpace most contemporary dramas that come out because of its remarkable focus and integrated content and form. And yet, it holds an iconic status, wedded to a transformative event - the true debut of Brando in all his rather startling power - that allows the film to be regarded as a true classic, as well. And while so many people concentrate on Brando's electrifying performance - and rightly so - I never hear enough about Leigh's contribution here, a performance equally ferocious in its daring to be so open and naked in chronicling a woman's descent into madness. Kazan, marrying his Actors Studio method of personal, interior motivation for characterizations with Leigh's consummate skills as a film performer (two very different techniques), creates with the actress one of the single most devastating portrayals of mental illness ever committed to the screen.

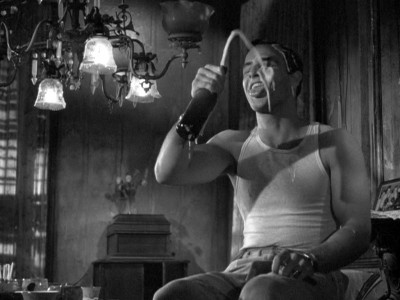

While Kazan fills the screen with audio/visual representations of a troubled mind (booming loud noises, echoing voices, lights flashing constantly, Blanche's frequent hot baths - she even mentions hydrotherapy, perhaps alluding to past mental hospital treatments?), and invents bits of business to further bring her altered state to light (such as Blanche's constantly staying out bright lights, or moving lamp shades to filter the harsh light...and harsher truths of her life), it's Leigh's symphony of conflicting emotions played out delicately on that lovely yet fading face that truly illuminates Blanche's coming disintegration. As for Brando, what more can be said here? A quantum leap in naturalistic acting, Brando's "debut" here (he had in fact already starred in 1950's The Men) must have been a sensationalistic thrill for those regular moviegoers who were used to the more conventional depictions of American "maleness" embodied by popular actors of the time, such as Robert Taylor (who had the number one movie of the year in Quo Vadis), Gregory Peck or Humphrey Bogart (who famously beat out Brando for the Oscar that year for his hilariously funny turn in The African Queen). While I've never gone in for rating such different acting techniques in regards to one type being "superior" to another - Brando could do things Peck couldn't dream of, but Bogart and Heston occupied different spheres that Brando unsuccessfully attempted, too - there's no denying that what Brando achieves here is evolutionary, and still remarkably powerful.

Careful to keep Stanley sympathetic (to a degree) at the beginning of the film, Kazan and Brando clearly get a jolt out of having the sweaty, scratching Stanley grin like the Cheshire cat as he first sizes up Blanche (who's obviously attracted and repulsed by this force of primitive nature). Stanley, a decorated war hero, is at first comically brought off as a dirt common truth-lover, spouting off hysterical warnings about Louisiana's "Napoleonic Code" and his lawyer and jewelry friends who will come by and straighten out Blanche's affairs. But as Kazan tightens the noose on Blanche's sanity and her safety in the apartment, and as her last bastion of pretense is shattered when Stanley cruelly tells Mitch of her sordid past as a prostitute, Stanley is shown to be exactly what Blanche first suspected he was: an animal, with zero sympathy or even a modicum of understanding for Blanche's situation (or his own wife's, who's in the hospital having his baby). Sensing his moment with his wife gone, Stanley toys with Blanche in the empty apartment, like a cat with a terrified mouse, first proffering a phoney reconciliation to further intensify his pleasure, before destroying her with a vicious rape (Kazan employs a crude shock edit after the rape of a water hose flushing garbage down a gutter). Later, when even his close friends obviously believe Stanley raped her (and, importantly, disapprove of his actions), and Blanche is led away to a mental institution, the viewer may believe that Blanche's complete breakdown is as much tied into Stella not believing her story about what Stanley did, as it is to Stanley's act itself.

Williams, adapting his own play for the screen, has difficulty getting the crucial subplot of Blanche's boy husband's death "right" for 1951's movie screens (the character's homosexuality is only alluded to in the most vague terms), but even the removal of the most blatant references to Blanche's prostitution activities cannot blunt that particular subtext, and it's still surprisingly potent. Perhaps that's due to Williams' strange, poetic-sounding dialogue that reverberates as metered even when it's crude and vulgar. There are so many declarations in A Streetcar Named Desire that have passed into the lexicon of great movie lines - "Funerals are pretty compared to deaths," "Fine feathers and furs," "How about cuttin' the rebop!" "Who do you think you are, a pair of queens?" "I don't want realism...I want magic!", "I've had many meetings with strangers," "I never lied in my heart," "Deliberate cruelty is not forgivable," and of course, one of the most memorable, and telling, lines in movie history, "Whoever you are...I've always depended on the kindness of strangers" - that just listening to the film is akin to hearing some strange, hyped-up, epic gothic poem of brutishness, sexuality, and madness. Coupling those haunting, delicate-and-then-vicious lines with transcendent performances and a director immersed in the visual and aural codes of the subject's internal truths, A Streetcar Named Desire remains that rare classic film that doesn't diminish in power or truthfulness regardless of what has come after it.

EAST OF EDEN

From originator to perhaps imitator? Director Elia Kazan, failing to secure Brando for the part of Cal in the big-screen adaptation of John Steinbeck's East of Eden, eventually went with relative newcomer James Dean, beginning a three feature film-starring career that would immortalize the young Method actor when he was killed in a car accident in 1955. Adapted by Paul Osborn, East of Eden severely truncates Steinbeck's massive tome, presenting only the final third or so of the novel in portraying the Biblically inspired sibling conflicts between "bad son" Cal Trask (James Dean) and "good son" Aron (Richard Davalos). Set in 1917 just prior to America's entry into WWI, the story focuses on Cal's efforts to win not only the approval and love of his father, Salinas, California farmer Adam Trask (Raymond Massey), but also his efforts to understand why his estranged mother Kate (Jo Van Fleet), who lives in rough-and-tumble Monterey where she runs a brothel, left his father. Aron's fiancé, Abra (Julie Harris), attracted initially to the danger of Cal, finds herself increasingly unable to meet Aron's idealized notion of what their life together will be - a naive, false image of a wife and mother that Aron mistakenly believes was also his mother's, whom he believes is dead. She increasingly finds herself drawn to Cal, a development that sends Aron off to war, and brings Cal's and Adam's relationship to a powerful new level.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Having just watched and reviewed the 1981 ABC miniseries of Steinbeck's East of Eden, I have to say that after watching Kazan's version again, I found some of it wanting as far as story and character development go. Of course, it's akin to sacrilege among reviewers and historians to suggest that anything involving Dean and Kazan would be anything less than "classic" - particularly when compared to something as calculated and "disposable" as a TV miniseries. But the severe telescoping of the storyline, especially at the expense of the Kate character, renders Kazan's East of Eden a visually sumptuous but dramatically undernourished widescreen '50s epic, with, thankfully, some interesting performances to compliment the careful compositions.

Aided by cinematographer Ted McCord's beautifully constructed frames, Kazan captures the beauty and power of the Northern California landscapes quite well, creating evocative sequences that show a careful attention to bringing out the story's subtexts through the mise-en-scene (the depictions of Kate walking through town like some kind of grim death angel are particularly effective). And of course, the images of Dean, decked out in early Americana middle-class attire like white flannel pants and short, tight sweaters, riding the rails or laying down in his bean fields, lovingly watching his young plants grow, are now iconic moments that hold an appeal all their own outside the film's own justification. Except for a reliance in critical moments for severely angled shots of characters in conflict (yes, we get it: a skewed world for a skewed relationship), Kazan's film is carefully, thoughtfully composed.

It's a pity, though, that the characters' motivations aren't better integrated into the film's visual design (something Kazan had no difficulty with in the superior Streetcar). The loss (or the deliberate elimination) of Kate's backstory irreparably harms the story because now we have a simple (yet still muddled) treatise on "good and bad" sons and the father that doesn't understand them. In the novel and the miniseries, Kate's outright evilness is luridly highlighted; she's far from the sympathetic character that Osborn and Kazan draw here. Since the film can't even say outright that she's a madame in a whorehouse, this censorship further ameliorates the character, with her declaration that she shot Adam because he wanted to "own" her making little sense without the prior knowledge that Kate despised, by her very nature, anything inherently good or kind. The film seems to start out as a quest by Cal to rediscover his mother while coming to an understanding of who she is and what she stands for in the story. But as soon as Kate lends him the money needed for his bean fields, and when she acts merely as a prop in the scene where Cal brings Aron to see her, to shatter his idealized vision of her, she disappears from the story. Does she get a chance to talk to Aron? Does Cal come to some kind of acceptance or rejection of her past actions? We never know because Kate only serves as a convenient signpost for the equally vague complications between Cal and Adam.

Whenever I read anything about East of Eden, I always seem to come away with the impression that most people view it as some kind of statement of the misunderstood Cal rebelling against the strict religious outlook of his father, Adam (the Bible reading scene would seem to be the source of this). But trying to decipher the characters' motivations in this abbreviated take on Steinbeck's work, it's difficult to get beyond a surface reading of that particular outlook. While Adam is shown as gruff and dismissive of Cal on several occasions (the ice house scene), he's also shown as loving and caring to Cal - in his own way - as he tries to reach out to Cal. Cal, on the other hand, seems to go along with Abra's "tyranny of the victim" mentality when she outlines how she felt better when she decided to forgive her father for her own feeling that he didn't love her enough (perhaps that kind of self-centered, egotistic illogic appealed to the nervous teens who adored Dean and this film when it first came out). Cal may have genuine feelings of abandonment or jealousy in his relationship with his father, but that dynamic isn't made nearly clear enough in the film, particularly when the Aron character is so shadowy and inconsequential as he appears here. Without any grounding in how Adam treats both Aron and Cal, and with Adam frequently shown as perhaps a misguided but still essentially loving father who continually tries to understand his son, telling him he has the power to make his own good choices (hardly an intolerant religious attitude), that kind of facile "rebelling against narrow religiosity" hardly works here.

East of Eden works best, though, in its scenes between Dean and Harris, as they work out their initial attraction and come to fall in love with each other. In those scenes, Kazan finds his rhythm perfectly (as he would in similar, but darker, scenes in Splendor in the Grass), with the luminous Harris and the subdued Dean becoming a touching portrait of young, searching lovers. When Dean is modified and "gentled" by the intuitive, empathetic Harris (who's a dream here), he seems to come close to the hype that has since submerged his actual on-screen talents and created this seemingly untouchable iconic status as one of the "greatest actors of the 20th century." Regardless of where you might fall on that particular rating, there's no denying that when Dean is quiet and expressive and responding to an actor that's equally giving, he projects a sensitivity and an openness that's quite powerful. It's only when Dean is imitating Brando (a fair judgment held then by everyone who knew the two actors) that his overacting borders on the unfortunately misguided and broad. Dean's confrontation scene with his father, when he gives him the bean money only to have it rejected as war profiteering, starts off well, but then degenerates into cheap, actorly tricks, until Dean is reduced to a grotesque, whimpering and crying for his father. That scene has never played as anything other than gimmicky to me - a feeling I was shocked to see echoed by critic Richard Schickel, who contributes a commentary track to this film (I rarely agree with Schickel, but since we're in-tune with this particular scene...). Those kind of broad moments, moments which must have impressed the teens who never got to see those kind of showy, easy, emotional pyrotechnics coming from teens in previous mainstream films, continue to fuel the Dean legacy, which is a shame when they overshadow the quieter moments where Dean truly did excel.

REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE

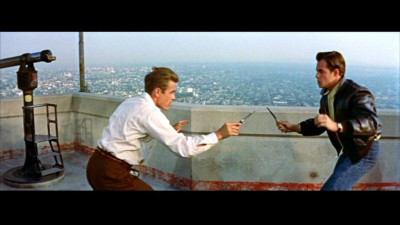

Transfer student Jim Stark (James Dean) is having a rough first day at his new Los Angeles high school. The night before, he was arrested for D & D, having to endure the particularly embarrassing scene of his parents, Frank (Jim Backus) and Carol (Ann Doran) fighting between themselves when picking Jim up from the police station. Having spied "good girl going bad" Judy (Natalie Wood) and "poor neglected rich boy" John "Plato" Crawford (Sal Mineo) at the station, Jim tries to befriend Judy the next day on the way to school (she lives nearby), but Judy responds by saying he's a "real yo-yo" and a "new disease" as she laughs it up with the punk crowd, led by dangerous Buzz Gunderson (Corey Allen). Things go from bad to worse when the field trip to the Griffith Park Observatory not only puts a dismissive point on the anxious teens' worries (the astronomer, in his narration, says "the problems of man are naive and trivial and of little consequence"), but also when Buzz decides to play with knives with new meat Jim. Bloodied and challenged to a "chickie run" with Buzz, Jim tries to get a handle on how to be a man with his apron-wearing father (skip it, Jim), before, newly attired in stoplight-red windbreaker, he heads off into the night to drive against Buzz. But tragedy results, and soon Plato and Judy join Jim on a night of unexpected revelation and further catastrophe.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Certainly the film that has provided the template for all that Dean represents as a cultish, iconic figure, Rebel Without a Cause is easy shorthand now for anyone wanting to allude to the infinitely more complex societal issues such as conformity, teen rebellion, generational battles, and parental complicity in teen violence that were hot-button issues in 1950s America. Watching the film now, it's almost impossible to escape out from under the decades of myth-making and pop culture associations that now come attached to it. As such, I've always found Rebel Without a Cause a beautifully designed, glossier-than-expected teen delinquent film with "serious" issues on its mind - issues that aren't always successfully articulated or explored. Looking at the film without considering Dean's iconography, director Nick Ray creates an almost dream-like Los Angeles (saturated, colorful daylight, and dark, foreboding, underworld nighttime) devoid of any kind of grounding reality as Jim traverses a 24-hour nightmare of parental discord, failed peer pressure acceptance, a right of manly passage, a tragic death, and a heated, romantic run from the law, hiding out in an abandoned mansion as he plays house with "wife" Judy and troubled "son" Plato - before cartoonish violence again interrupts, with Plato killed by the police. It has a driving, jazzy, hyped-up kick that I can imagine was well appreciated by kids looking for thrills in drive-ins and theatre balconies all over the country.

It isn't dismissive to write that Rebel Without a Cause works best as a the "Gone With the Wind of teen exploitation flicks," because Rebel obviously has so much going on, both visually and thematically. It's trying to say something new and different about the condition of new, modern teens in 1955 urban America, and those messages are souped up by Ray's electrifying CinemaScope visuals and the moments of surging action and violence that punctuate the many dialogue scenes. Now, whether those messages transcend or at least match the visuals may be another point entirely. With the obvious Freudian dynamic going on between Jim's weak, henpecked husband (the sight of frilly apron-clad Mr. Magoo on his hands and knees, worriedly picking up a mess he made before his shrewish wife discovers it, is a particularly nauseating sequence), his hectoring wife, and Jim's inexpressive desire to have his father become a man so he can become a man, it's not like Rebel Without a Cause is exactly a subtle work. These are broad, coarse strokes about society, parents, children, and their place within a world that can blow up at any second (the planetarium show might as well be about the atom bombing blowing up the Earth). There's nothing particularly mystifying or perhaps even new about them. Their vitality and freshness comes from Ray's spirited re-imaginings of them within the CinemaScope frame.

Unfortunately though, in a worrying trend after his few over-the-top moments in East of Eden, Dean indulges in some more Methody shtick that plays almost like a parody of what many people thought Brando was doing (and indeed, what Brando would eventually devolved into when he turned to self-parody). The opening scene, evidently totally improvised, has Dean doing his patented "odd/cute" bit with the mechanical toy monkey, that seems revelatory until one realizes it's really not much more than a trick, a gimmick (but Christ, how insulting for Warners to tack their big, bold titles over it, so you're straining to see Dean's performance). It's so obviously designed to be showy and important, that the delivery system outweighs any true emotional or revelatory value it might possess. And that kind of display happens often in Rebel, particularly in the following police station scene (Dean's siren imitation, his bogus desk-beating scene, and his "You're tearing me apart!" shouting bit that today, if attempted by any actor, would elicit giggles, not stunned acceptance). Where Dean shows his skill and artistry are again, as in Eden, in the romantic scenes with lovely Natalie Wood, where he's quiet, and caring, and sensitive, listening to his fellow actor and responding intuitively to them, rather than coming up with studied, showy bits of business. It's impossible (and pointless, really) to surmise if Dean would continue this kind of performing in future films he never made (his last, Giant, is a performance so closed-off it seems delivered down into his chest). But clearly by Rebel, Dean was indulging in moments of Brando-hero worshiping (and thinking that the gimmicks had to be bigger and more noticeable to somehow be more "valid") when his true, lasting appeal and skill may have lied in his more conventional, more honest moments.

CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF

"The truth is pain and sweat, and paying bills and making love to a woman that you don't love anymore. The truth is dreams that don't come true, and nobody prints your name in the paper till you die."

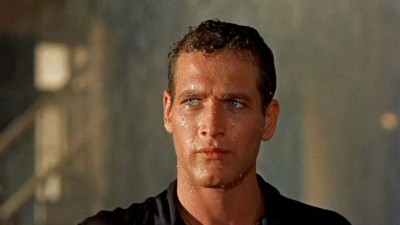

A thoroughly conventional but satisfying film of the late 1950s Hollywood school of big-named, big behind-the-scenes talent potboiler dramas, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof may be based on a Tennessee Williams play, but much of the perverse heat of Williams' tale has been softened for mainstream 1958 audiences, while the glamorous aspects of having beauties like Taylor and Newman emoting on the screen alongside heavyweight pros like Carter and Ives, have been highlighted to deliver an essentially safe yet entertaining experience. Visiting at the palatial Southern estate of "Big Daddy" Pollitt (Burl Ives), son Brick Pollitt (Paul Newman) is having no difficulty staying away from his cat-in-heat wife, Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor). Disgusted with her sexuality - particularly when he believes that she cheated on him with his best friend, who committed suicide afterwards - Brick is enduring this visit only at her insistence because it looks like Big Daddy is dying. Released from the hospital, Big Daddy believes he's beat cancer, and he's hoping to live his remaining years making himself happy - plans which don't include his frivolous, hysterical wife, "Big Momma" (Judith Anderson). Eldest son "Gooper" (Jack Carson), along with his pregnant, scheming wife Mae (Madeleine Sherwood), smell blood in the water for Big Daddy's birthday celebration, and have drawn up succession plans for Big Daddy's estate. But scrapper Maggie is having none of that, knowing that if she's to have a piece of the pie - as well as Brick's love back - Brick has to come to terms with her and Big Daddy.

SPOILERS ALERT!

To say that Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is "safe" is again not demeaning, the same way that saying Rebel Without a Cause is exciting while not being particularly meaningful still results in a valuable film. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof endured the same fate that other Williams' plays suffered at the hands of the film censors, losing much of the central subtext that actually drives the story. In his play, Brick is a homosexual who can't navigate his feelings and relationship with the unseen Skipper, his college football hero/friend, nor subsequently his wife, Maggie. On the screen, some kind of reasonable justification had to be found for Newman hating the sight of luscious Taylor in a skin-tight slip (homosexuality is no excuse for not wanting to sleep with Elizabeth Taylor), so writer/director Richard Brooks, who had a reputation in Hollywood (good or bad is up to you) for adapting literary and stage works, comes up with an awkward, cockamamie story about Skipper flubbing a pass from Taylor, and his weak, cowardly friendship being rejected by Newman - a justification that still doesn't make any emotional sense to me even after numerous viewings of the film. Barring that subplot, Brooks highlights a thoroughly familiar one of Brick reconnecting with his dying father that, although well-scripted and performed, is as safe as Williams' original vision would have been daring and compelling.

That said, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof delivers big, showy, dramatic moments by the superlative cast that satisfy our need for supposedly hard-hitting but ultimately comfortable truths. Taylor, looking more impossibly beautiful than she ever had or would again look in a film, fits best with Williams' vision of a carnal little climber who uses her sex to hang on to the weak man she knows will come around...if he only sleeps with her one more time. Newman tries mightily, but since his character doesn't really make much sense, he's reduced in impact next to Taylor and particularly Ives. Burl Ives dominates every time he's on the screen, and he has several big scenes that play well to his persona. When Big Daddy lays down the law about "lies and liars," complaining about the overwhelming "odor of mendacity" in the air, it's hard not to find sublime pleasure in a performer clearly suited to his material. Ives, a far more talented performer than he was frequently given credit for on the screen (Taylor, too, for that matter), has the film's best moment where he discusses his father, a tramp who died without a nickel in his jeans and a smile on his face. It's a beautiful scene, full of regret and truth and ultimately happiness, but it's muted by the facility of its framework within the "Brick reconnects with his father" main plot. And unfortunately, that's the overall effect of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, a drama filled with isolated moments of real power, designed, however, for minimally offensive effect. It's enjoyable to be sure, but ultimately, inconsequential.

The DVD:

The Video:

I would assume that since the set-ups of the individual discs are the same as the special editions, these transfers are probably the same, as well. All of them maintain the correct anamorphic widescreen ratios (except, of course, full-framed Streetcar), while presenting fairly clean, crisp images. Grain is definitely a factor in Cat and Rebel, but overall, color values are quite good (even though Cat at times has some greenish color shifts), while compression issues are minor, at worst.

The Audio:

Eden and Rebel are presented in surprisingly strong Dolby English Surround 5.1 audio mixes that give full throat to their stunning scores. Unfortunately, Cat is only presented in a Dolby English mono, while Streetcar maintains its original mono audio track. There's a Dolby French 2.0 stereo mix for Eden, while the remaining films have French mono mixes, as well. All of the titles include English, French and Spanish subtitles, and English close-captions.

The Extras:

Streetcar includes a wonderfully entertaining and informative full-length commentary track featuring Karl Malden and historians Rudy Behlmer and Jeff Young (recorded separately and combined here). There's also an Elia Kazan movie trailer gallery (the 70s re-release of the title is pretty funny, skewing it all towards Brando). Eden includes an insightful commentary track by Richard Schickel, along with the theatrical trailer. Rebel has a full-length commentary track by author Douglas L. Rathgeb (The Making of Rebel Without a Cause), along with the original trailer, while Cat has a commentary track by author Donald Spoto, along with the original theatrical trailer and a featurette doc, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: Playing Cat and Mouse which is light on insight and facts, frankly.

Final Thoughts:

TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection: Romantic Dramas is a great, inexpensive way to own these four influential, entertaining titles (along with a few fun extras) without having to lay out bigger bucks for their special editions (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof appears to have all the special edition features). Transfers are quite good, even though a lot of people still balk at the flipper discs (I'm not a big fan, but they do save space and money). I highly recommend TCM Greatest Classic Films Collection: Romantic Dramas.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||