| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Man Called Horse, A

Originally a Cinema Center Films production released by National General, the picture is now in the hands of CBS with the Blu-ray distributed by Paramount. The 1080p presentation is generally excellent, though the original film source incorporates a lot of grainy stock shots and a surprising number of opticals, all of which distract slightly from an otherwise sharp image. There are no extra features but audio and subtitle options galore.

A Man Called Horse is daring in that, except for the opening sequence, the entire picture takes place within a "primitive" Sioux community, and most of the dialogue is in the Sioux language and not subtitled. Bored English aristocrat John Morgan (Harris) is hunting for game that, he sighs, is not all that different from that found back home in England. As the picture begins Sioux braves sneak up to Morgan's camp to steal the horses, killing his guide (Dub Taylor, with his teeth out) and his two helpers (James Gammon and William Jordan). The white men are graphically scalped, and in a grimly amusing bit, the Indians are disappointed to find the guide quite bald, making his scalp hardly worth the effort.

Morgan is taken alive and made sport of by his captors. The leader of the tribe, Chief Yellow Hand (Manu Tupou, actually Fijian), declares Morgan a "horse" and treats him like one, leading him around on a kind of leash. Morgan is made a slave of Yellow Hand's crotchety mother, Buffalo Cow Head (Judith Anderson), and the white man bides his time, hoping for a chance to escape his captors. He learns more about the tribe from its only other Caucasian (and only other white character in the film), Batise (Jean Gascon), a French-immigrant who, five years into his captivity and after being deliberately hamstrung after trying to escape, has become its fool.

The film compares unfavorably to Arthur Penn's outstanding Little Big Man, released later that same year. They operate from the same premise, of a white man captured by Indians, who in both films is initially terrified but who gradually comes to respect and even admire his captors. (There are several other plot points nearly identical that I won't spoil here.) Stylistically the films are miles apart, however, with Little Big Man singularly picaresque, mixing satire with tragedy while drawing parallels between the genocide of the American Indian and the war in Vietnam, particularly the My Lai Massacre. It's still one of the five or six best Westerns ever made.

By contrast, A Man Called Horse is nearly humorless, uneasily mixing apparently authentic Sioux traditions with pseudo-mysticism, drawing obvious parallels between Morgan's search for meaning in his unhappy life ("I'm looking," he says at the beginning of the picture, "Just looking") with similarly dissatisfied late-'60s youth.

The film works best when it watches Morgan observing the behavior of his captors, much of which he doesn't understand and which the film wisely doesn't try to explain. A mother learning that her son was killed in battle immediately reaches for a knife and cuts off a finger, then gives away her possessions and, with no one left to care for her, prepares herself for an agonizing death by starvation and exposure that winter - concepts reminiscent of Ballad of Narayama.

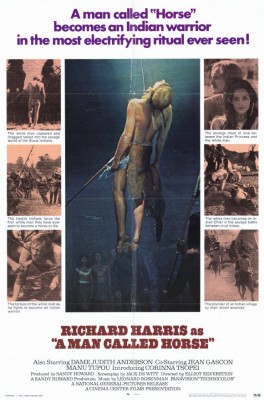

In the film's most celebrated scene (note the poster above), Morgan willingly subjects himself to a Sun Dance ritual in order to obtain warrior status. The strange ritual includes piercing Morgan's chest with the meat-hook-like talons of a large bird, which are then attached to ropes raising Morgan several feet into the air, the skin on his chest nearly ripped from his body in the process.

The medicine man supervising this ritual is played by actor Iron Eyes Cody, symbolizing the film's alternately authentic / phony air. Cody was for years one of the most instantly recognizable Native American actors, best known for a famous series of "Keep America Beautiful" public service announcements. Only problem was Cody was actually the son of Sicilian immigrants and born Espera Oscar de Corti, though Cody's wife was an Indian, as were their adopted children, and Cody himself was a tireless advocate of Indian causes. (And, to be fair, back in 1970 Cody's real roots would have been unknown to the filmmakers, not that it would have mattered.)

This mix of the authentic and inauthentic seriously damages the film, though by 1970 standards only real Indians and historians recognized its inaccuracies. Judith Anderson (wearing black contact lenses) is believable as the crusty, crabby Buffalo Cow Head, but Harris's love interest, Running Deer (Greek actress Corinna Tsopei) looks ridiculous, like Ann-Margret in a black wig.

The film's emphasis on grisly ritual - versus the wisdom expressed by Old Lodge Skins, played by Chief Dan George, throughout Little Big Man - make its supposed respect for Indian culture at least appear slightly disingenuous. Further, the idea of a white man winning over his captors and (mild spoilers) rising to great heights within the tribe is pure fantasy, a backhandedly arrogant and imperialist notion perpetuated to the present day in movies like Dances with Wolves (1990) and The Last Samurai (2003). Little Big Man, for all its tall tales, is much more realistic; Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) is accepted into his tribe (his being captured in childhood helps), but he's always regarded as an adopted outsider and never fully embraced or truly accepted by Indians and, later, whites alike.

The film had its roots in a short story by Dorothy M. Jackson, whose The Hanging Tree and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance were memorably adapted into movies. The TV series Wagon Train filmed A Man Called Horse first, as a March 1958 episode featuring Ralph Meeker as Morgan, Michael Pate as the chief and Celia Lovsky as his mother. The 1970 film version was popular enough to spawn two sequels: The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976) and Triumphs of a Man Called Horse (1983).

Elliot Silverstein directed. He's best known for his TV work (including several episodes of Naked City, Twilight Zone and The Defenders) before successfully debuting in features with Cat Ballou. For whatever reason A Man Called Horse didn't lead to bigger things for Silverstein, whose only other films that decade were two modestly-produced horror films, Nightmare Honeymoon (1974) and the fun if derivative The Car (1977). He went back to TV after that.

His direction is exemplified by Morgan's hallucinatory experiences - sequences with nearly as many silly ideas as good ones. (Of the latter is an interesting shot of Morgan literally shedding his western worldly ways as a fierce wind rips the European clothes off his body, like Glenn Manning caught in the H-bomb blast in The Amazing Colossal Man.) Still, his direction is sincere and impressively if flamboyantly visual and visually the movie is frequently arresting.

Video & Audio

Filmed in Panavision with original prints by Technicolor, A Man Called Horse generally looks fantastic though viewers will want to keep in mind that it frequently cuts away to grainy stock shots of wildlife, there's an abundance of opticals (mostly confined to the mystical scenes), and even some post-production manipulation, i.e., editing choices accomplished via an optical printer. But some shots are startling sharp and hardly seem four decades old. There are no Extra Features, but the disc includes myriad audio and subtitle options. The English 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio and English Stereo Surround track for my money mixes the mono dialog too low, but services Leonard Rosenman's score well. Optional tracks in Castilian, German, French, and Latin Spanish are included, with subtitles in all those languages plus Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Swedish, and Norwegian.

Parting Thoughts

The unusualness of A Man Called Horse, its still-shocking violence, and interesting if flawed take on the Native American experience add up to a film worth seeing once, warts and all. For all its problems it's inarguably stylistically unique among Western films, if somewhat misguided. Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV's audio commentary for AnimEigo's Tora-san, a DVD boxed set, is on sale now.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||