| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Anger (La Rabbia), The

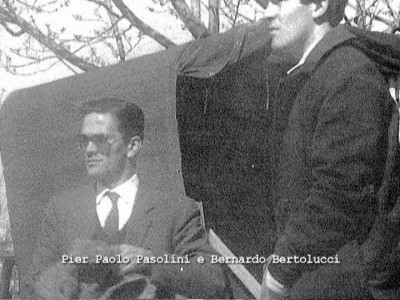

Late in co-director Giovannini Guareschi's half of the two-part 1963 Italian film The Anger (La Rabbia), he cuts to footage of Soviet scientists examining a dog onto which they have surgically grafted the living head of another dog. This bizarre laboratory-created creature is meant, by the right-wing Guareschi, to demonstrate the deviant "unnaturalness" of the Communists, but it would also work rather well as a metaphor for the film itself. Concocted by Italian film producers--who invited lefty filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (Mamma Roma, Salo) to edit together newsreel material and add his commentary to create a film that would then be run successively with Guareshi's piece--The Anger is a cinematic experiment in ideological pugilism, a two-headed beast that, like the one Guareschi flashes at us so gleefully, alternately intrigues, fascinates, informs, and appalls.

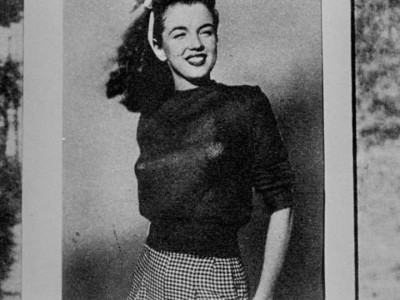

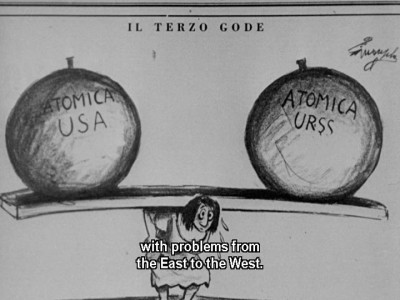

The period's turbulent rush of troubling events and issues is familiar to anyone who's been following Mad Men: Cuba, Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, the international rebellion against institutionalized racism, the nuclear arms race. In this context, the film's producers posed a question to be answered by each filmmaker in their turn: "Why is our life dominated by discontent, by anguish, by the fear of war, by war?" If we reduce it down completely, the answer to this question from either side is fairly predictable and incompatible one with the other: Pasolini blames capitalism, and Guareschi holds Marxism guilty. But, contrary to the hopes of the film's producers, the appeal of The Anger is not in a face-off of ideologies, one of which will trump the other in a no-holds-barred, pro wrestling-style takedown (this format is in most ways not a precursor to the often genuinely petty, anti-intellectual brawling of the 24/7 cable-news cycle in 2011). The real interest of the film lies instead in the contrast between the two directors' styles, which elicits the sneaking suspicion that artistic form is not really separable from political convictions, if by political convictions we mean the way one views the world.

Thus, the section curated, edited, and written by Pasolini--the first half--is elegiac and poetic (he was, in addition to being a well-regarded filmmaker, a highly acclaimed poet, essayist, and semiotician). The footage he has chosen of then-recent events depicts the military suppression of the anti-Soviet uprising in Hungary in 1956, which he finds regrettable; the liberation of multiple African colonies from their European colonizers, which he celebrates; the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in England; the rise of rock 'n roll youth culture in Italy; Khrushchev welcoming a Soviet astronaut back to earth; the life of the then recently-departed Marilyn Monroe recapped in a photo-montage; and nightmarish flashes of nuclear weapons tests seen from multiple terrifying angles (the seemingly incongruous line Pasolini draws between Monroe's succumbing to suicide and the world's fear of its own potential suicidal annihilation by nuclear missile anticipates that in Nic Roeg's Insignificance). He castigates the wealthier classes, juxtaposing images of them, elegantly dressed in luxurious surroundings, with troubling documentation of working and impoverished-class oppression; he clearly implies that the former's sheltered ignorance or active greed is what ultimately makes the latter possible. This is all done with clear, passionately burning conviction, but it is more sad than strident; however naive one might find his particular political beliefs (I, for one, would never characterize Pasolini as naive), he clearly believes that happiness and equality for all people should be the common goal, and his words add an emotion that reminds us of the impossibility of ever really separating the personal from the political.

On the other hand, the no-holds-barred stridency of Guareschi's approach more than makes up for Pasolini's lack of such superciliousness. Guareschi, who was not so much a writer or intellectual as a political cartoonist (and, it has to be admitted, a fairly good one, at least when it came to making cute drawings), addresses many of the same events and even uses some similar-appearing footage; but he relies on a tone that is savage, mocking. Whereas Pasolini saw the then increasingly victorious African struggle against European colonialism as a great victory, and the rapidly awakening consciousness of and opposition to deep-running international racism as a necessary step toward an actually humane world, Guareschi spends most of his film bemoaning Europe's (especially Italy's) loss of empire after World War II. He adopts a shamelessly jingoistic, race-baiting attitude, playing zany-sounding music over footage of the liberation celebrations in former European colonies to drive home his suggestion that the African people were better off--less "savage"--under the armed, occupying thumb of white Europeans. The use of that music is indicative of the level--snide where Pasolini was sincere--at which Guareschi is operating. He disguises his brutal, repellent ideas with a tone of clever, facetious, smug irony, a strategy all too familiar to anyone who's had the misfortune of hearing Rush Limbaugh sully the talk-radio airwaves with his "satirical" "Barack the Magic Negro" poison. Guareschi is obsessed with "tradition" in the form of those dangerous, simpleminded opiates, blindly nationalist "patriotism" and empire. For just one example, the hypocrisy of his right-wing position is revealed in his gleeful put-downs of then-President Kennedy and the United States. Pasolini has, of course, proffered some objections to American ideology and foreign policy in his preceding musings; but Guareschi objects to the United States' privileged, powerful post-WWII position not because of any moral objections to abuses of privilege and power, but simply because it is Europe and Italy that, in his view, are the rightful occupiers of the world's throne. Having been on the losing side of the war even leads him to what is perhaps the most shocking, almost funny bit of nonsense in his parade of distortions: his smearing of the Nuremberg Trials, an international attempt to acknowledge and redress the Holocaust, as nothing more than a U.S. power grab and act of vengeful humiliation directed against the defeated Axis powers.

Though utterly incompatible and less in dialogue with one another than seeming to occupy their own separate planets, the film's two halves are very watchable, each "entertaining" in its own way--Pasolini's as a compelling, impassioned demand for justice in the world we all share, Guareschi's as a revealing observation of the fearful, reactionary thought processes of an ultra-nationalist right-winger. There is, of course, no considering The Anger on a purely aesthetic level, somehow apart from the political perspective espoused by each of the filmmakers in his turn; if there were, the film would lose its reason for existing in the first place. But the film does have an aesthetic component, inseparable though it is from its political preoccupations, which is the interesting case it makes that the content of one's politics will at least partly determine the form of one's creative expression. It could soundly and legitimately be argued, when watching The Anger, that the melancholy concern and ultimate hope of Pasolini's contribution spring just as naturally from his politics as the derisive, embittered, sarcastic approach of Guareschi's does from his.

THE DVD:

The Anger, presented here in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, is comprised entirely of newsreel footage and other documentary sources, meaning that the film was never pristine-looking to begin with. Raro has evidently taken every step to assure that the integrity of the film's original, intentionally rough texture has been preserved, which is to say it looks like it's obviously meant to, and there are no distracting external flaws in the transfer.

Sound:The sound in the pre-existing footage used by Pasolini and Guareschi, though presented in a clean Dolby digital 2.0 format, reveals the same innate limitations as the video; but this is part of the The Anger's texture and feel. The narration and music, while occasionally stifled or crackly, also reflect the sound technology used in the creation of the film. The Anger is not a technologically advanced affair, sonically speaking, but neither does it need to be, and all due care has been taken to preserve the aural experience of the film.

Extras:Raro Video has done contemporary viewers of The Anger a tremendous service by providing a rich goldmine of contextualizing supplements. The most essential is Tatti Sanguineti's 2008 documentary, La Rabbia I, La Rabbia II, La Rabbia III, which features interviews with Italian cinematic experts as well as individuals (Pasolini collaborators, Guareschi's son) who were peripherally involved in the making of the film. The convoluted story behind The Anger's conception, execution, and almost immediately suppressed release is very nearly as interesting as the film itself (the "final" version of the film, or at least the one we have, is La Rabbia II, which was apparently the result of producer-enforced compromise), and this in-depth look gives us all the details and plenty of relevant commentary as food for thought.

The disc also includes a beautiful color documentary/essay short film by Pasolini from 1964, Le Mura di Sana'a, which was made as a cinematic plea for UNESCO to intervene and help preserve the ancient beauty of Sana'a, Yemen's capital city, from the ugly and destructive modernization brought along with the relatively recent arrival of international capitalism to the impoverished area.

A gorgeously designed booklet (it's really more like a little book) included as an insert is packed to bursting with yet more commentary and background: Pasolini's and Guareschi's contentious written "dedications" to one another of their respective halves of the film, and a bevy of writings representing multifarious, fascinatingly divergent views from both the time of the film's release and now.

Finally, Raro has included all four(!) of the film's theatrical trailers, which represent the successive attempts (all ultimately backfired) of the producers/distributors to find an "angle" from which to successfully market the film.

FINAL THOUGHTS:A riveting experiment in politicized cinema, The Anger is a clear must for any admirer of the great Pasolini, but it's also required viewing for anyone looking to gain some insight into either the specific world events of the period or, more generally, the relationship between politics, propaganda, and creative personalities and processes. It has the potential to anger and bemuse as well as edify and enlighten, but there is never a dull moment, and Raro Video has performed something of a cinematic miracle in rescuing this one from obscurity. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||