| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

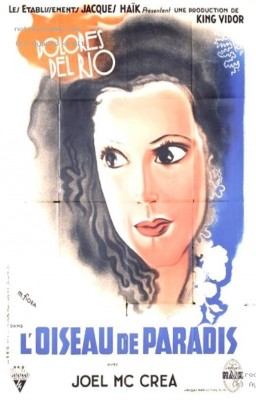

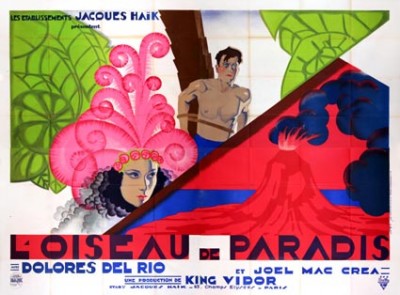

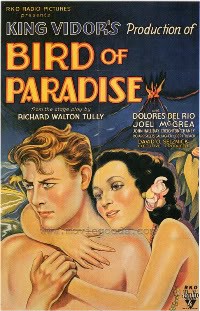

Bird of Paradise: Kino Classics Edition

A pre-Code wildflower that carries an indelible whiff of the risqué (even by today's standards), future Stella Dallas and Duel in the Sun director King Vidor's 1932 film Bird of Paradise -- rescued from its ultra-perishable original silver nitrate media and preserved on 35 mm film by the George Eastman House, and now presented by Kino Classics in this new Blu-ray edition -- is outrageous on several levels. Adventure story, sexy romance, and unreconstructed-racist fantasy projection/act of unmitigated exoticization, the film has accumulated layers of different kinds of value over its 90 years: Its seafaring, death-defying action is still rousing, its overpoweringly physical, overheated, and tragic love story still incredibly sensuous for something from the Depression era, and all of that raw energy still pumps swiftly through its hot-blooded veins. But it now holds additional interest, too: to film scholars and historians, as a marker of what one could get away with in American movies before Breen Office prudishness took hold in 1934, and as a work that bears fascinating vestiges of the transition from silents to talkies; and to the culturally and sociologically-minded, as a time capsule holding some genuinely naïve and thus straightforward (or shameless, if you prefer) examples of colonialist-era, way pre-racial enlightenment attitudes toward non-white, non-American customs, beliefs, languages, and skin colors.

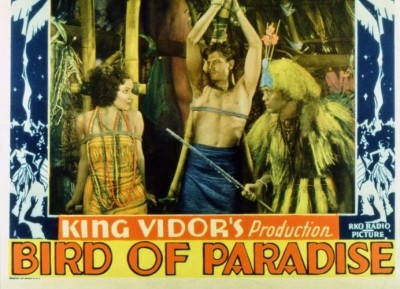

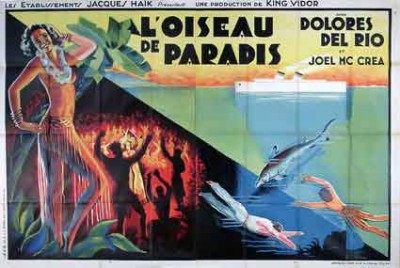

The film's pure-fantasy tone, which makes its ludicrous conceptions of "foreign" people and ways at least somewhat more palatable, is set from the get-go, when we're introduced to the crew of a vessel voyaging in the South Seas: the cocktail-mixing party guy and the big softie clearly too pampered for life at sea (both very "gay" characters supporting The Celluloid Closet's case that such flamboyant personages were one of the first things to go when the Hays Code began to be enforced), along with an affable skipper (Wade Boteler) with a fatherly attitude toward our handsome, strapping young sailor-protagonist, Johnny (Joel McCrea, Sullivan's Travels), seem to spend most of their time drinking, playing cards, and exchanging repartee. It's a swell cocktail party at sea until they approach a narrow passage near what's vaguely referred to as "one of the Virgin Islands"; after barely making it through (in one of the film's several abrupt upshifts into indulgent thrills of one sort or another), the boat is greeted by a fleet of native islanders in canoes with whom the sailors start up a large-scale, friendly splash fight that's rudely interrupted by a hungry shark, to which Johnny plays prey and from which he's rescued by a mysterious, beautiful native girl, Luana (Dolores del Rio).

Johnny and Luana fall hard for each other in a very memorable sequence -- reminiscent of the gorgeously erotic underwater romantic fantasy Jean Vigo so magically concocted for L'Atalante -- in which Luana lures Johnny from the boat for a little barely-clad night swimming in the sea, their respective body languages communicating in a sort of luminous, dreamily shot underwater ballet of flirtatious evasion and pursuit -- and Johnny decides to stay on the island until the ship passes by again some time later. In the meantime, however, he will discover that the "taboo" nature of his paramour that his shipmates were teasing him about is for real and deadly serious: Luana is a princess, the daughter of a leader of the tribe, and betrothed to a native prince. Defying this inevitability, Johnny, in an act of daring rescue and escape, whisks Luana right out from under her husband-to-be's nose in the middle of their wedding ceremony, followed by an interlude wherein the two become a sort of South Seas Adam and Eve, alone together in an idyll away from the prejudices and restrictions of their respective societies, though Johnny never does stop talking like a back-slapping American Joe, and it is, of course, Luana who will learn his language, not the other way around. (As one of the more noticeable indications of Bird of Paradise's silent-to-talkie transitional nature and reminders of Vidor's long pre-sound Hollywood career, several onscreen-text bits of labeling and exposition, like the one that opens this section and reads "PARADISE - the secluded island of Lani," appear over the course of the film.) But the volcano god Pele is, according to the islanders' belief, angered by this breach, roiling and belching smoke and threatening to erupt (Pele is a Hawaiian deity, actually, but this film's concern is less concerned with accuracy than creating a more or less interchangeable islander "type"); tracking down Luana and Johnny, then sacrificing them to the volcano's hungry maw, is the one sure way to appease it. Only the most serendipitous twist can save them, and even if that comes to pass, their love is, tragically, not meant to be, and each will have to return, lovelorn and alone (and, in Luana's case, destined to save her people by sacrificing her life) to their own world.

The headstrong, notoriously interfering David O. Selznick produced Bird of Paradise, and as with Hitchcock's also Selznick-produced 1940 film Rebecca, it's a hybrid of the director's vision and the producer's, with sheer action, spectacle, and titillation vying for pride of place with the parts more likely attributable to Vidor, such as the aforementioned lyrical underwater love-swim or a strikingly composed, very low-angle shot that frames Johnny as a tiny figure against a vast tropical sky as he prepares to leap down onto an oversized palm tree. This back-and-forth of sensibility actually dovetails well with the film's episodic structure, with long digressions for "tribal" dance numbers and that rapturous stretch of the lovers alone on their island wherein del Rio, a strategically-placed lei barely covering her lovely femininity, and the similarly stripped-down McCrea just frolic in the flora under the sun and emit their palpable chemistry. The film still holds onto the plot as its guidewire and through-line, though, and the alternation of rapid-fire eventfulness with exotic(ized), sensuous languor that comes off less choppy than like a string pulled taut, then allowed to go slack for a spell, then pulled back to plot-driven tension again -- not at all an unpleasant effect.

What could be construed as unpleasant is Bird of Paradise's helpless condescension to Luana and her tribe, through which they are reduced to little beyond that hoary old ethnocentric repository of dark, alluring, dangerous "savagery" and the unfettered sex and violence of the "uncivilized." The ostensible tribal language and customs shown in elaborate, gyrating dance-performance rituals and the silly backwardness of the way the natives talk and behave are, to put it mildly, probably not based on any kind of anthropological or ethnological research; they're so clearly Hollywood fantasies of a scary-sexy-exotic Other that, from the perspective of 2012, they appear more like a satire of long-discarded notions than anything vicious or poisonous. It's not so much that they're now harmless as that what's harmful in them has simply lost its potency; at this point, most things in the film seem equally far-fetched, whimsical -- a light breeze of tropical escapism with strong undertones of brimstone for danger and musk for the raw release of unbounded sexuality. However problematic it may remain in some respects, in its best sections it still has the power to transport a viewer into a state of delirious, escapist sun-and-sea euphoria -- its vision of paradise as, simultaneously, the idyllic serenity of heaven and the burning passions of the other place is presented by Vidor and Selznick in a strange, uniquely cinematic potion of sound and vision that saturates the senses and leaves you inflamed and intoxicated.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG4, 1080/24p transfer, presented in the picture's original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, shows its age with fairly frequent scratching, flicker, and even a jittering frame or two, but considering that the film has been restored and preserved from a nitrate (i.e., extremely perishable) source, this is undoubtedly the best-looking available extant print of the film, and it certainly has been cleaned up to a passable degree, with the bonus of not having too much of its texture digital-noise-reduced away.

Sound:The uncompressed PCM 2.0 monaural soundtrack is rather harsh; it has a distant, somewhat distorted, tinny-speaker quality to it throughout, but at least this flaw is consistent, suggesting that any measures that could have been taken with the sound probably were, and some of the poorness in sound quality may even be due to the sound technology of the period shortly after the pictures started talking or, more probably, the innate audio flaws in a very old and very fragile nitrate print transferred, fuzzy sound intact, to 35 mm. It's neither inaudible nor awful to listen to, but in general terms, as forgivable as it is considering the circumstances, Bird of Paradise has sound quality inferior to what one usually hopes for (and, under more favorable conditions, has a right to expect) from Blu-ray editions of even older films.

Extras:Nothing other than some trailers for other Kino Classics releases: Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, Nothing Sacred, and A Star is Born.

One of Hollywood's strangest, sexiest pre-Code fever dreams, King Vidor's 1932 Bird of Paradise is a potentially tawdry tale of a seafaring sexual adventure to the tropics that transcends its titillation (though it does have plenty in the way of the risqué going on) to offer up a true dream world -- a sheerly escapist, almost entirely invented analogue to any recognizable reality, with Dolores del Rio no more believable as its "native" Virgin Isles princess as Joel McCrea is as the seasoned sailor, and it doesn't matter, because their attractive limbs here look like they were made for the sole purpose of being entwined. The whole thing plays like the sexually/racially charged fantasy of a "civilized" (read: white) dreamer as regards a voraciously fetishized and irrationally feared darker people, but as potentially problematic as that is, it enhances rather than saps the film's interest. At this point, its story of the forbidden, intensely erotic passion between a muscular white American and a bronze, nubile islander feels much less like actually objectionable racial simplemindedness than a privileged peek into someone's (perhaps even yours or mine) fascinating, delirious, delusional subconscious, not to be taken at face value; it plays like a wet dream, with about as much plausibility and with the same odd, sometimes unexpectedly beautiful and focused intensity. It's rife with a kind of quasi-pornographic reduction of character to erotically physical presence, but however crude its racial and cultural assumptions may be, the appeal and power of Bird of Paradise survives its surface nonsense and soars anyway, escaping the fate of being a mere relic through its unique narrative structure, potent imagery, and the palpable eroticism and chemistry that engulfs its two leads in a swooning, hyperdramatic blaze of passionate sensuality and doomed love so hot that it leaves the viewer a little singed in its wake, too. Recommended

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||