| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Samurai Trilogy (Musashi Miyamoto / Duel at Ichijoji Temple / Duel at Ganryu Island), The

For Blu-ray, the three films have been digitally restored and that's the big selling point here. Even if you've seen them multiple times on various formats (as I have), the improvement between the DVD version and the Blu-ray is striking. The image is markedly sharper and steadier, and the colors are more vivid and less greenish than past releases. Watching them in high-definition isn't quite the revelation of the best high-def transfers, but nonetheless the results are extremely impressive.

Curiously, the movies have never been accompanied by very much in the way of extra features, and while this release adds a few new items, supplements-wise the set is a little disappointing.

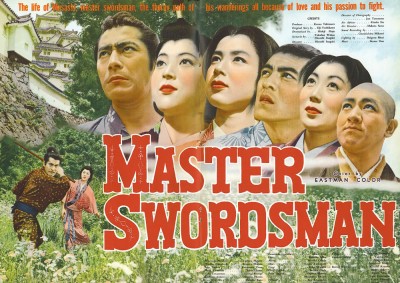

Beautiful image created for Toho's international sales division c. 1954-55, shortly before rights to the first picture were licensed to actor William Holden.

The trilogy follows the spiritual evolution of real-life master swordsman Musashi Miyamoto (c. 1584-1645), whose The Book of Five Rings is still required reading for any serious practitioner of the martial arts. In Japanese popular culture his life has been dramatized almost continuously in every medium - on television, radio, the movies, manga, the stage - and in this sense he is to Japan what Robin Hood, Wyatt Earp, or the Three Musketeers are to western world audiences, an endlessly fascinating character pliable to myriad interpretations.

The first film, today known as Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto (Miyamoto Musashi, 1954), recounts the master swordsman's early life and spiritual awakening, when as an illiterate peasant known as Takezo (played in all three films by Toshiro Mifune) he becomes a fugitive but captured by a sympathetic Buddhist priest, Takuan (Kuroemon Onoe). The priest essentially tames this wild animal of a man by tying him up and hanging him from a large tree for several days and nights, and later he locks him in a book-filled chamber at Himeji Castle, where three years later he reemerges as samurai Musashi Miyamoto.

In the episodic Samurai II: Duel at Ichijoji Temple (Zoku Miyamoto Musashi - Ichijoji no ketto, or "Musashi Miyamoto Sequel - Duel at Ichijoji Temple," 1955), Musashi battles chain-and-sickle master Old Baiken (Eijiro Tono), challenges the master (Akihiko Hirata, Godzilla) of the Yoshioka School in Kyoto, and first encounters his greatest rival, ambitious expert swordsman Kojiro Sasaki (Koji Tsuruta). That film ends with a spectacular swordfight pitting Musashi against 80-odd Yoshioka men.

In Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island (Miyamoto Musashi konketsuhen - Ketto Ganryushima, or "Musashi Miyamoto Conclusion - Duel at Ganryu Island," 1956) the focus shifts more toward narcissist Kojiro Sasaki, with actor Koji Tsuruta even top-billed over Mifune, and concluding with the duel of the title, strikingly photographed on a beach at sunrise.

The series as a whole follows Musashi from his youthful ambitions and materialism through his years of training and honing his swordplay skills, only to discover, as they say in Sanjuro, the best sword is kept in its scabbard. He all but gives up fighting duels while Sasaki, by contrast, aspires to the high-paying position of fencing master to Lord Yagyu. By the time he squares off with Kojiro Sasaki, Musashi is using a simple, quickly-carved sword made of wood.

Like many, perhaps even most of the film and television versions of Musashi Miyamoto, this was adapted from Eiji Yoshikawa's serialized novel, which was to Musashi much like what Robert Graves's speculative but exhaustively researched I, Claudius was to its subject. In bringing it to the screen, director Hiroshi Inagaki and screenwriter Tokuhei Wakao adapted a kind of Classics Illustrated approach. In other words, a standard, workmanlike adaptation that hits all the right notes, but which also puts polish and production showmanship ahead of innovation and especially revisionism, Cecil B. De Mille and not William Wyler.

Ironically, in Japan, it is Tomu Uchida's five-film adaptation (1961-1964)* of the same story, this time starring Kinnosuke Nakamura and filmed at Toei, that is considered the definitive movie Musashi. (Intriguingly, Mifune with his working-class looks makes a better Takezo than Musashi Miyamoto, while Nakamura, with his background in Kabuki, is an excellent Musashi but an unconvincing Takezo.) That series is finally available on DVD in America, but until recently was virtually unknown in the west, while the Inagaki-Mifune trilogy, while popular at the time of its release, isn't particularly famous in Japan.

Clearly, when it was made the studio behind its production, Toho, was thinking in terms of the international market. Western interest in Japanese cinema had begun in the early 1950s with the release of Kurosawa's Rashomon, which won the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival followed by distribution sales around the globe, including America. For the next seven or eight years, Toho and Daiei especially coveted additional film prizes and the potentially global market their most prestigious films might draw. To that end, because it was perceived that Western audiences preferred traditional Japanese costume dramas, the studios dusted off perennially popular stories like Musashi Miyamoto for lavish color (and, later, widescreen) productions. Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto was among the first Japanese features in color.

These films attracted interest from members of the Hollywood film community, people like director John Huston, who directed The Barbarian and the Geisha (1958) on location in Japan because he admired the Japanese's use of widescreen and color; and Asiaphile actor William Holden, who was so enamored of Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto that he acquired U.S. theatrical rights. He got behind the film in a big way, narrating its English version, apparently appearing onscreen in the original coming attractions trailer, and campaigning, successfully, for it to be nominated for an Academy Award as the best foreign language release of 1955. Though many wrongly assume Seven Samurai won the Oscar that year, in fact it was the William Holden version of Samurai I that did. Without his passionate support the film might be completely unknown in the west and largely forgotten in Japan, as Inagaki's three-film Kojiro Sasaki (1950-51) has, even though that series also features Mifune as Musashi. Indeed, without Holden's help, interest in Japanese cinema generally might have foundered by the late 1950s, instead of flourishing as it did.

All three films are incredibly handsome to look at, showing off Toho's belated postwar recovery following several bitter and severely damaging strikes in the late 1940s. Toho at this time was comparable to the big Hollywood studios a decade before, with hundreds of experienced technicians and a veritable corral of contract players, who populate these and innumerable other Toho movies, enhancing them with their presence. All three pictures co-star Kaoru Yachigusa and Mariko Okada as Musashi's love interests, and the series helped solidify each actress's screen persona, the former as the refined virginal, traditional and wholesome ingénue (still active, in recent years she's become the quintessential Japanese grandmother), while the latter came to specialize in good-bad girl roles similar to her one here. The first picture miscasts Rentaro Mikuni as Musashi's weak-willed friend Matahachi; he'd play Priest Takuan in the Toei series with greater success, while Samurai I's priest, Kuroemon Onoe, makes little impression. However, Eijiro Tono and Akihiko Hirata are fun to watch in Samurai II, as are Daisuke Kato and Haruo Tanaka in Part III.

Video & Audio

Criterion's notes state all three films were sourced from 35mm low-contrast prints struck from original camera negatives. That's entirely believable given their impressive sharpness here. Various camera department people who worked at Toho in the 1950s have told me the studio continue to use nitrate film stock as late as 1956; I don't know if that would apply to the Eastman Color Samurai Trilogy, but possibly. In any case the access to original camera negative elements combined with some digital restoration has resulted not just in a more detailed picture but significantly improved color. Past home video versions leaned much greener than now, which is truer and more vivid at the same time. The audio, Japanese only (with optional English subtitles) on this Region A set, was likewise impressively restored using 35mm optical positives. The first two films, running 93 and 103 minutes, are on Disc One, while the third feature, running 105 minutes, is on Disc Two.

Extra Features

Supplements include a 24-page booklet with essays by Stephen Prince and William Scott Wilson, essays that, respectively, provide background on the film and which discusses Musashi Miyamoto's The Book of Five Rings. Japanese trailers with English subtitles for all three pictures are included. These appear to be older standard-definition masters bumped up to high-def for this release. Finally, Wilson appears on-camera to discuss the real-life Musashi Miyamoto. Personally, I was hoping for material on William Holden's influential involvement in the film's first American release, and much more material on director Inagaki and members of the cast and crew, but what's here is okay.

Parting Thoughts

A colorful historical epic that also can serve as an excellent introduction to the jidai-geki ("period drama") genre and postwar Japanese film generally, The Samurai Trilogy is unquestionably worth an upgrade and a DVD Talk Collector Series title.

* Full Disclosure: I produced special features and did an audio commentary for AnimEigo's release of the Tomu Uchida/Kinnosuke Nakamura Musashi Miyamoto.

Stuart Galbraith IV is a Kyoto-based film historian whose work includes film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features. Visit Stuart's Cine Blogarama here.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||