| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

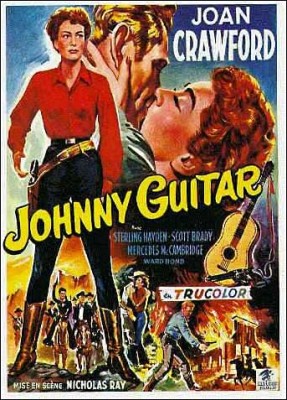

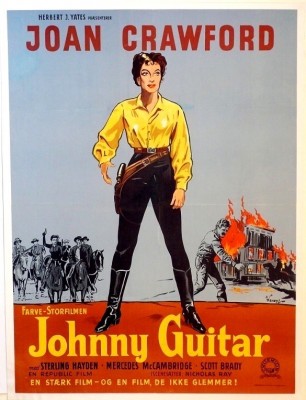

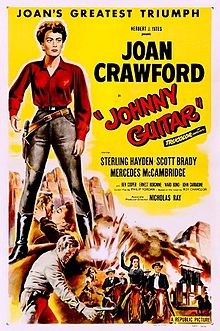

Johnny Guitar

It swaggers self-consciously, conspicuously into town in a blaze of too-much TruColor, exuding a kind of charisma, mystery, and just plain confident, transfixing oddness that makes it deeply, genuinely alluring; you'd have to have all the steely fortitude and skepticism of principal player Joan Crawford's saloon proprietress herself to resist its overripe, infallible allure. I'm referring, of course, to the great 1954 Western Johnny Guitar, one of director Nicholas Ray's masterpieces (he also brought Rebel Without a Cause, In a Lonely Place, and Bigger than Life into being). It seems unfathomable when you're caught up in its singular raptures, but the film actually has a history of being unfairly maligned and neglected, save for by those French New Wave critics/filmmakers (Jean-Luc Godard in particular) who were the very first to appreciate it and admire it after it was mostly rejected at home. However, acknowledgment of the film's indefatigable brilliance has long since triumphed, and now, after years of requests and pining on the part DVD region "1A" cinephiles, it has finally been dusted off and given richly-deserved, long-overdue new life for the first time in North America since VHS, in the form of a stunning new Blu-ray edition. Much better late than never (and, if we had to wait this long for a release this well-done and respectful of the film's visual and aural virtues, it's been worth it); no exploration of American cinema is complete without some serious, intent exposure to Johnny Guitar, which, 20 years before the glory days of McCabe & Mrs. Miller revisionism, right in the thick of Eisenhower-era enforced optimism, had the imagination and guts to remake that most beloved, rich, popular, and problematic American film genre, the Western, in its own incorrigible, inspired, ingenious image.

Crawford stars as Vienna, a businesswoman who is trying to get her saloon/gambling parlor to thrive by welcoming and working with the railway men that have expressed interest in running their new routes near Vienna's (already, this turns the Western convention upside down; railway expansion is, here, unequivocally positive, not an intrusion to be fended off). She faces almost supernaturally ferocious opposition to connecting their little settlement's isolated provincialism to the rest of the nation from her rival, bank owner Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge), a prude and harridan who nurses a shame-laden crush on a shady local gunslinger known as The Dancin' Kid (Scott Brady); the Kid, for his part, carries a torch only for Vienna, who can take him or leave him, both facts driving Emma insane with anguished envy. The ambitious, independent Vienna (who, we infer, has built her business by prostituting herself in one way or another before finally achieving financial and romantic independence) just wants to stake her claim to this space in the world and make what's hers as successful as it can be, but she's stifled and nearly crushed, sitting as she does at the apex of not one, but two love triangles: the one with the Dancin' Kid and Emma at its other points, and the other with the Kid on one side and an irresistible man from her past on the other -- a man she's loved and lost, one she's looked for and never found in all the other men she's been involved with.

That man (tall, cocky Sterling Hayden, (The Killing) is the figure who gives the movie its title; he rolls into town, cocky and self-reliant (and oddly pacifist, preferring the guitar slung over his back to firearms despite what will prove to be his crack marksmanship) after being hired by Vienna as entertainment in hopes of drawing elusive customers to her out-of-the-way joint. As he arrives, he witnesses a stagecoach holdup in which Emma's brother has been murdered, and soon thereafter finds himself nearly out of a job when Emma, hellbent on pinning the murder and her loss on the Dancin' Kid and his gang (which includes Ernest Borgnine as the shady Bart and Ben Cooper as "Turkey" Ralston, a too-young man for the Wild West, for whom the tough Vienna has unlikely, affectionate, near-maternal feelings), and asserting Vienna's nonexistent, unprovable guilt by association. Johnny and Vienna, it is revealed through their sexually-tense verbal sparring, have known each other a long time and share tortuously romantic memories, and his real reason for accepting her offer of work was to rekindle the love between them that, he hopes, can still come to be. She resists; she's been too deeply hurt by him in the past, and she obviously has other things on her mind. Johnny finds himself embroiled in all of her troubles, too, which gives him the chance to prove his fortitude and loyalty to her as she becomes the victim of full-fledged mob justice that the unstoppable Emma has whipped up by coercing, bullying, and lying to the community and local authorities. Accusations fly; motivations, feelings, loyalties, and revelations escalate into tangling complications and physical/emotional jeopardies, allowing Ray to reach and sustain an array of melodramatic top notes (exquisitely aided and abetted by Victor Young's sweeping, melancholy score, most atypical and unexpected for what is ostensibly a Western, over which Peggy Lee spine-tingingly intones lyrics over the end credits as she sings the title tune). That the film will culminate in a capital-r Romantic exteriorization of its torrential, high-running emotions via a lynching, a mountaintop showdown, and an infernal blaze seems natural and inevitable.

Not that being "natural" in a literal sense is anywhere to be found on the film's laundry list of well-achieved artistic ambitions. This is not in any way a down-to-earth or realistic/naturalistic excursion; Ray never demonstrated much interest in those modes (nor would they have suited his vision), but Johnny Guitar is the ne plus ultra of his intense style, bursting beyond even the ultra-heightened realities he would sear onto celluloid for Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger than Life. He and his cast and crew create what looks and feels wholly like an unabashed representation, something that revels in its own artifice and uses it for all it's worth -- a living painting; an opera in which the lyrics are all spoken, not sung; or a passion play with a wronged, martyred saloon-running, insufficiently passive/obedient woman about to be crucified by the ignorant, envious enemies, traitors, and Pharisees that surround her. Every movement, every interaction between every character, right down to the delicious, frequently epigrammatic dialogue, is like perfectly executed choreography. Ray's building and prolongation of tonal and dramatic tension through luxurious, languorous pacing (achieved in collaboration with editor Richard Van Enger), refracted through the transfixing boldness (in both composition and the film's sumptuous, bright, primary TruColor processing) of the images he creates with cinematographer Harry Stradling (A Streetcar Named Desire) creates a of ravishing pageantry that you couldn't take your eyes off of if you wanted to (you don't).

A good, convincing case has been made for interpreting Johnny Guitar as an allegory for the Red-Scare witch hunts that running rampant during the period in which it was made and released, with the lasciviously, demonically savage, duplicitous and singleminded crusader Emma a perfect stand-in for bullying Red-baiter Joe McCarthy; the Dancin' Kid's team for the squabbling, disorganized, benign American Left; and Vienna and Johnny Guitar as more tolerant, progressive, open-minded bringers and nurturers of culture unfairly caught up in the panicked, treacherous, finger-pointing atmosphere. The film does work beautifully as just such a parable, but even years and decades from now, when that connection might not seem so obvious, Johnny Guitar will still pack its tremendous surge of evocative power. Its more general, elemental dichotomies -- real conscience and honor vs. "traditional," received, presumptuous pack-mentality moralizing; letting one's fellow man be vs. violently crusading for conformity; the welcoming embrace of love and sexuality vs. shamed, furtive, warping repression -- will still be resonant, its stylistic boldness all-enveloping and searing, its delirious colors rendering cinephiles feverish and scholars obsessed (whole articles and books could be written on the color-coding in the costumes alone, if they haven't already). Johnny Guitar will always do its own voluptuous, inflamed, impassioned, thing, and do it masterfully, sublimely well; its untamable freshness will always hit you anew every time you revisit it, and it will never seem quite like any other film.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The things you learn when researching aspect ratios.... Apparently, Johnny Guitar was technically composed for a 1.66:1 widescreen aspect ratio, but is presented here (as it has been on every home video release) at its full-frame 1.37:1 aspect ratio. This is correct, too, if not precisely "preferred"; upon its release, the film was simply reframed through matting for wider screens and projected in both ratios (and made with the knowledge that this would be the case), since many theaters in 1954 still did not have wide screens to accommodate a 1.66:1 AR. To this reviewer's eyes, the film looks finely composed the way it is presented here. On the PQ front, it appears that all the vital celluloid texture is present and accounted for (no over-doing of digital noise reduction), with no compression artifacts and only very slight and intermittent signs of print wear (very light scratches, one instance of noticeable debris, a couple moments of flickering in and out, etc.) The colors look stunning, almost always rich and solid. This is, by very far, the best we've ever seen Johnny Guitar look on the home screen.

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 soundtrack faithfully reproduces the film's mono sound, with all the nicely cleaned-up, full-sounding, crisp and clear resonance (with no noticeable imbalance or distortion at any point), in both dialogue and music, available in the one channel of sound the filmmakers were working with.

Extras:"The Martin Scorsese Presentation of Johnny Guitar,", an eloquent and enthusiastic three-minute video introduction (from around 1995) by Scorsese, one of the film's longtime champions.

Director Nicholas Ray was one of the boldest iconoclasts to ever work in Hollywood, and his 1954 masterpiece Johnny Guitar -- which takes on the venerable Western and transforms it into something wondrous strange, an indelibly vivid TruColor pastiche, political allegory, lurid American dream and nightmare -- is perhaps his most iconoclastic film of all. Desert-bound in the wild American days of Westward expansion, saloon proprietress Joan Crawford and ferociously prim, sexually repressed bank owner Mercedes McCambridge pull away from a comparatively standard-issue boys' pack of gunslingers, outlaws, and lawmen to fight a mythic battle that pitches the forces of "good" -- nonconformist pluck, courage, and resourcefulness (Crawford) -- against those of puritanical, prejudicial, fundamentalist (in the broadest sense of the term) "evil" (McCambridge), with Sterling Hayden as a freewheeling, quasi-bohemian spirit returned from Crawford's past, the only guy with the honor, integrity, and independence to melt her self-protectively hardened, seemingly invulnerable heart and become her lover and ally. Ray pushes the tempestuous, frenzied vigor latent in his playing of (often fascinatingly gender-reversed and otherwise subverted) Western-picture archetypes against each other as far as it can possibly go, and it works magnificently: He makes Johnny Guitar soar into the realm of sheer pulp poetry. Every moment is a rush of fearless filmmaking and hard-earned, overpoweringly effective grandiosity; the rhythm and pitch (however high) are perfect, engrossing and enrapturing from start to finish. This monumentally strange, strangely monumental, exhilarating film stands, nearly 60 years after it was wrongly dismissed by confused critics, as a top-tier classic that's long outlasted its early detractors and emerged from a decades-long cocoon of cult objectification and obsessive critical analysis to come into its own, widely acknowledged and praised as a wildly successful experiment, a near-unbelievable creative risk that never stops paying off, and one of the great, eccentric, inimitable and indispensable cinematic achievements of all time. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||