| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Rosetta: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional and other sources, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

"My name is Rosetta.... I found a job.... I made a friend.... I have a normal life.... I won't be left by the wayside."

When we first meet Rosetta (the brilliant, unforgettable Émilie Dequenne (The Girl on the Train)), she's already on the move. Dressed for some sort of manufacturing/fabrication job in a hairnet and protective coat, and moving at a very brisk pace through a factory (the camera follows her so closely, and the place is so anonymous, we can't tell exactly what product is made there), she's running -- whether away from something or toward something, we don't really know, and it remains an open question for most of the film. It turns out that she's on her way to confront a coworker she suspects of getting her fired, but it doesn't make any difference; her trial period is over, the boss informs her, and she has no job there any longer, at which point she has to be chased down and physically removed, she's grasping so hard at anything she can grab hold of in this workplace where she wants so badly to remain as a productive part of a whole. What follows are a handful of days and nights in the life of this 16-year-old Belgian girl, who lives in near-destitution in a trailer with her alcoholic mother, as she desperately searches for some semblance of a place in the world around her that she can cling to, some entryway into a society she's determined with every iota of her anxious, ferociously energetic being to earn her way into. Rosetta's story is thus that of a poor (or, as we might more politely call her, "disadvantaged") girl's search for meaningful work, and in that respect, it can be placed in a proud lineage of Neorealist fables that take the time to consider, dramatize, and humanize society's (that is, our Western-industrialized-democratic society's) perpetual unjustly rejected, invisible, forgotten underclasses. Under the rigorous, often unbelievably acute, and exquisitely sensitive camera eye of the great Belgian filmmaking brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (The Son, L'Enfant), however, Rosetta's prosaic but inflamed quest for a way to earn her keep and be a legitimate part of our production-consumption cycle becomes something more sacred, urgent, and shattering than virtually anything you've ever seen on film.

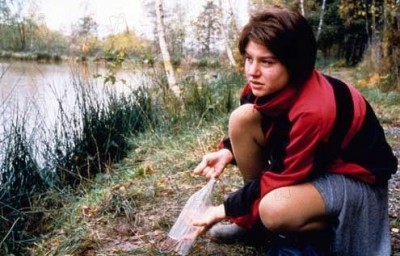

Dequenne inhabits this girl to such a full, fearless extent, she becomes almost scary, a force of nature: Rosetta's single-mindedness is never in doubt, and as we follow her through her predetermined, obviously entrenched subsistence routines -- by necessity ducking in and out of dangerous, high-speed highway traffic to get to the clearly wrong side of the road that she lives on; going to her hiding place and switching out her somewhat presentable sidewalk-trampling shoes for rubber boots more appropriate to the muddy trailer-park lawns; the gathering of fish from traps she's set in a nearby river to save money on food; manually hauling heavy, bulky propane tanks/returning empties between the concierge's hovel and her trailer; and dealing, in a brittle, self-protective way, with a stubbornly helpless, childlike, alcoholic mother (Anne Yernaux), whom Rosetta must literally chase and corral in an attempt to get her into rehab, and whom Rosetta finds prostituting herself to that awful, stingy, grim-faced concierge so she can spend her daughter's hard-earned rent money on booze -- we come to understand the character's single-mindedness very well, right from the inside of Rosetta's experience, which comes at her every day like a tidal wave and threatens to wash her away if she doesn't push back hard (Dequenne, beautifully, gives her a fierce, lumbering yet harried gait, as if she's always walking against a strong, opposing wind). Rosetta has seemingly been predestined by her life to not belong, to not have any of the dignity or stability the majority of us take for granted, and something instinctive-verging-on-violent in her knows that's wrong, and will not accept it. The stress of her never-ending fight to be noticed and taken in by an indifferent world, her staunch refusal to be vulnerable or dwell on her own needs (for a mother that actually mothers, or for some peace, security, and maybe some enjoyment in life) for even a moment lest she sink down and disappear forever, has even led to some recurrent, agonizing abdominal attacks (an ulcer?) for which her stopgap measure is aspirin and blowing her tender belly with a hair dryer for some relief. But for Rosetta, finding that elusive employment is a life-or-death struggle, and stopping to take care of herself is not an option.

After the firing that opens the film, desperately trying to get a little cash from the second-hand clothes her mother sometimes mends, and checking in with every inefficacious state worker she knows to go to, all of whom appear to know her and yet again have no job for her (she doesn't even dignify one bureaucrat's offer of welfare with a response), Rosetta glumly stops at a waffle stand for a snack, and there she catches the eye of Riquet (Dardenne regular Fabrizio Rongione), the young man working behind the counter. Her eye, on the other hand, is on the boss/owner who's come to pick up the day's deposit (Olivier Gourmet, also a Dardenne perennial); she immediately asks him if there's work available but is brusquely rebuffed. Riquet tracks down Rosetta at the trailer park shortly thereafter, however, and after overcoming her initial hostility that he would take such liberties (and her possible embarrassment over the intense dispute about her mother's drinking she's just been through yet again), he informs her that a job has become available, after all. Rosetta enters an elated period, one in which she has a job and a true friend who seems to like her and have her back, whether or not she reciprocates what seems to be his shy romantic interest; Riquet even invites her over to his flat and awkwardly lets her in on his dream of becoming a rock drummer (even convincing her to dance a bit, though the stomach pains fight back against the dangerous possibility of such impractical, spontaneous joy).

But when her victory appears to be short-lived, with the boss offering her job to a son who's flunked out of school, Rosetta -- after another scene in which she refuses to leave a workplace that, she feels strongly, affords her life some legitimacy (you will not be able to keep your heart from breaking as she clings futilely to a sack of flour) -- betrays Riquet, her friend and helper, with horrible ease (it feels like a punch in the gut) in order to usurp his job. The painful wrong she does to Riquet presents the possibility that the harshness and constraint that are all life has meagerly allowed Rosetta have made a conscience -- what you might call a "soul" -- a luxury she cannot afford, and whether there might be some slim chance of her, with the angry and hurt Riquet haunting her, finding a way to the privileged view that the better-off among us are able to have -- the one that lets us see that human-level relationships are more important than economic advantage because we aren't usually forced to choose so directly between them. It's difficult to say whether the film's ending represents such a glimmer of hope or just a momentary reprieve, but by its final, profound moment, when Rosetta's callous, impenetrable, absolutely necessary emotional defenses are brought to the breaking point and breached, such distinctions seem irrelevant; it is, in one way or another, a redemption, a catharsis, a too-long-resisted revelation of Rosetta's overt, naked need to be both literally and figuratively helped up -- a point that had to be reached and lived through before any other good could be possible. Perhaps only the conclusion of Bresson's Pickpocket can compare for the sheer release, the simultaneous sense of liberation and sorrow one feels at this last glimpse of the now vulnerable -- which is to say, human in a way her life has thus far cruelly robbed her of-- Rosetta before we cut to black.

The Dardennes have often referred to Rosetta as a "war film," and its ultra-vérité, handheld style -- which throughout puts us in either intimately close proximity to Rosetta or has us struggling to keep up with her -- reflects that conception and makes her struggle for survival something that, while never spoken of or obviously reflected upon by any character in the film, is conveyed as an desperate battle through the finely achieved tone of every dynamic, too-close, improvised-feeling frame -- a tone that, paradoxically, could only be the result of painstaking and precise preparation. (The film's gorgeous way of capturing the flurry of Rosetta's experience under the mostly natural light sources, which lends an almost abstractly simple, very purely realist quality to the images, is courtesy of DP Alain Marcoen, who has shot every Dardenne picture.) And speaking of the immediacy of its style, if any film is incontrovertible proof that not all handheld-camera films are created equal, it's Rosetta. I have many problems with the facile, superficial, and arbitrary use of a spasmodically shaking camera seen in action pictures that would actually be more coherent and exciting with less obviously superimposed adrenaline, but the worst possible consequence of that tacked-on "realist" aesthetic would be to inure us to a film like Rosetta, where the documentary feel is vital to and inseparable from the meaning and effect of the story we're being told. It's a technique chosen for Rosetta by the Dardennes for such sound and well-considered reasons, and deployed so skillfully and with such unfailing focus and astute instinct, that it erases any line dividing the physical from the emotional, both in what's occurring onscreen and in our response to it.

Rosetta is not just a "war film," though; it is also ultimately a political film of the most meaningful and mindful variety (by political I mean, of course, cognizant of the ways in which society-wide priorities, values, and dominant ideologies inevitably and concretely affect individual lives). For one thing, along with such disparate brethren as Mike Leigh and Godard, the Dardennes are intent on depicting work as an integral and important part of life, not something secondary and uninteresting that should be elided to get to the good stuff (i.e., the supposedly unrelated drama/romance). That's certainly true in Rosetta, where our unemployed heroine has no greater vision of paradise, no higher or more frustratingly difficult to attain goal, than joining the "real" world of productive wage earners (as such, the film is also an implicit but severe rebuke to a certain conservative suspicion that anyone not working must simply not want to). Through this cinematic view, Dequenne's workday scenes with Gourmet, in which the boss teaches Rosetta the step-by-step procedure of making the waffle batter, become something wonderful, probably the happiest in the film, choreographed and captured by the directors with an unblinking, unsentimental eye toward the true, unembellished dignity of work, with no propagandistic socialist-realist romanticization to taint it. Rosetta is hardly a crusader à la Norma Rae, but the film makes all such liberally well-intentioned issue movies seem lax and desultory by comparison, because it takes you so directly and unflinchingly into, really almost inside of, the experience of someone fighting for what she senses is her right to survival with dignity, and against her systematic exclusion from participation in society (including, ultimately, her exclusion from the moral, humane concern for a fellow being that generally comes clear only after one no longer fears one's basic needs going unmet). In an extraordinarily consistent filmography comprised exclusively of films ranging from excellent to great, all partaking of the same opening out of clear-eyed sociopolitical consciousness into hard-won humanism and deeply empathetic but never pious storytelling, Rosetta may be the most pared-down and intensely moving work of all. It's an immersive, undeniable film that achieves and sustains an astonishing simplicity and an unerringly genuine poignancy -- a masterpiece that will retain its power to captivate and move (to honest, unjerked tears, if ever a movie could) for as long as motion pictures exist.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The transfer of Rosetta -- AVC/MPEG4-encoded, 1080p-mastered, presented widescreen at the original, theatrical aspect ratio of 1.66:1 -- is perfection, conveying every nuance and texture intended by the filmmakers, realized through their 16 mm guerrilla-style shooting and subsequent 35 mm blowup (enhancing the film's documentary-realist feel with more fitting, naturalistic-looking grain and blur than would occur in straight 35 mm shooting). You'd be hard pressed to find another transfer of a film with these particular visual demands onto a digital format that so knowledgeably, carefully preserves the film's very specific aesthetic properties; it's crystal clear upon inspection that the work was done by people (including longtime Dardenne Bros. cinematographer Alain Marcoen himself) who understand very well both what the film really looks like and how to bring it as close to that as possible for our home viewing experience.

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 soundtrack preserves the film's intensely but subtly present sound layer, comprised entirely of diegetic sound (no score, only one instance of in-scene music) perfectly; dialogue, foley, and ambient sound are all right there, crystal clear and integrated beautifully, with no distortion, imbalance, or even a hint of any other audio discrepancy or flaw to be heard at any point.

Extras:--An hour-long interview with Jeanne-Pierre and Luc Dardenne conducted by L.A. Weekly critic Scott Foundas. Foundas acquits himself very well and does the audience a huge service by being extremely succinct (I, for one, am so impressed with the Dardennes that I'm sure I would behave effusively, nervously, and self-indulgently in their presence, so kudos to Foundas for balancing his clear enthusiasm for and knowledge of the Dardennes' work with a professionalism and respect that defers, always, to the artists in the room), allowing the filmmakers to do at least 95% of the talking and letting them finish before he asks his next informed, specific, and relevant question. The brothers answer Foundas's well-put queries on Rosetta (regarding such matters as casting, preparation/research, and aesthetic/stylistic choices, etc.) in much well-recollected detail, and often with a good deal of unexpected humor, making for a lively and informative hour with two of our greatest living filmmakers.

--Interview with Émilie Dequenne and Olivier Gourmet, 18 minutes alternating separate interviews with the two actors in which perennial Dardenne troupe member Gourmet and grand discovery/one-timer (so far) Dequenne recount what it was like to work with the brothers. Of particular interest is their divulging of details about the extensive and rigorous preparation of character and performance one undergoes with the Dardennes, without the crew, followed by a shoot during which the crew, as a completely united front under their inimitably focused and visionary leaders (who, in their one resemblance to the Coens, are apparently of one mind, always, and have never been seen to disagree), scrambles to capture the now-ingrained actions and emotions on film -- a great insight into how the filmmakers create their particularly immediate sort of cinematic reality.

--The film's original theatrical trailer.

--A booklet insert featuring an essay on the film by critic Kent Jones.

The unavailability on North American Blu-ray/DVD of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardennes' great, great 1999 film Rosetta -- the profoundly touching story of an impoverished, life-hardened Belgian girl's quest for inclusion, through the honorability and "normality" of employment, in the relatively untroubled world most viewers probably already occupy -- is a longstanding, glaring omission that's finally been remedied by Criterion, with a fantastic Blu-ray treatment that has taken all pains necessary to bring the film to our home screens with every nuance of its stark, stunning, flawlessly achieved naturalism intact. It's rare enough to see a movie that actually attains this much genuine, deep-down simplicity and naturalness (it takes much more than a shaky handheld camera, though that is the perfectly apt and beautifully executed visual strategy the Dardennes have rightly chosen here), and rarer still for any film to reach the heights of pure, unstrained, overpowering empathy and emotion that Rosetta takes us to. It's a perfect film, but it does something especially wonderful, something all kinds of films have achieved their own perfection without doing, that puts it in an even more special category (at some very rarefied patch of cinematic ground where the deeply penetrating power of Bresson's pared-down, ultra-purified approach overlaps with the more direct Neorealist social consciousness of Rossellini or de Sica): It presents us with a character that is a person so real, so honest, so flawed and alive, so recognizably needy and difficult and human in her struggle, that her suffering becomes our own. Its relentless, amazing appearance of showing us, documentary-like, the bare facts and immediate, unembellished physical/emotional reality (those realities become inseparable through the sheer skill, focus, and deep discernment of the Dardennes's writing and directing) of Rosetta's life, doesn't allow us not to feel for and understand her and her situation -- her unfairly, insurmountably difficult existence reflecting a perpetual blind spot in supposedly "advanced" civilization that demands our contemplation as we experience its truth so vividly through Rosetta's story. Rosetta, so utterly free of any sanctimony, self-righteousness, "protest," condescension, grandiosity, or explicit sociological/political aim, thus becomes one of the most effective political films we've ever had, one of the noblest of all the great movies -- a work of empathy so conscientiously made, so radically effective that one doesn't feel entirely naïve for feeling that it might actually have the power to change the way we see and think about each other and our world. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||