| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

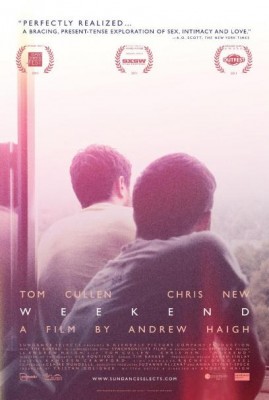

Weekend (2011): The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional sources, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

When my partner and I made one of our increasingly rare forays out to an actual movie theater earlier this year to see British filmmaker Andrew Haigh's celebrated Weekend, we were much less startled by its frank (if entirely un-self-conscious and non-exploitative) onscreen depictions of gay sex than we were by the middle-aged straight couple who walked out about five-sixths of the way through, we could only assume because of their mounting discomfort with the film's progressively more romantic and erotic love scenes. (We have since, not very nicely, referred to this couple as "the bourgeois bohemians" and made them our own firsthand exemplars of a certain liberal attitude that pats itself on its ostensibly brave and cultured back for going to see a "different" film like Weekend, only to show its true, prudish, retrogressive colors when confronted with sex it wouldn't blink an eye at were it being had by the more usual straight couple.) The walkout was a bit shocking, because Weekend is not in any way transgressive; it doesn't have a shock-value-seeking bone in its body, and its only act of "subversion" is its confident assumption that there is absolutely nothing shocking, unpleasant, or provocative about showing physical encounters between two fully fleshed-out, complex male characters who are attracted to one another, depicting their being together in a way that, with its close-up, relaxed explicitness, is perfectly well-suited to the film's aesthetic and narrative approach as a whole, and therefore not even gratuitous, let alone jarring or button-pushing.

At the most literal, plot level, Weekend is just exactly what the title promises: two days in the life of its two principal characters, a weekend during which a one-night stand occurs, with neither participant expecting anything more. But their having found each other, by accident or serendipity, at a certain crossroads in one another's lives makes for a completely unanticipated, much deeper bond between them, perhaps even love, whether they were looking for it or not (one enriching complication is that one was, the other wasn't). By the end of their all-too-brief journey, Haigh's emotional intelligence -- and the great care with which he, his actors, and his crew cause that sensitivity to resonate through the apparently small, mundane lives and worlds of its characters -- have made the situation flow over, immersing us in and engaging us entirely with the apparently workaday existence in a humdrum town (namely the mid-sized British-Midlands city of Nottingham) in which our imperfect but appealing mid-to-late twentysomething protagonists, Russell (Tom Cullen) and Glen (Chris New), have happened so fortunately, and ultimately so sadly, upon each other.

The way Russell and Glen get together is not a meet cute, a particularly auspicious beginning, or even necessarily the beginning of anything at all. The reserved, polite Russell -- an orphan whose family consists of Jamie (Jonathan Race), his longtime best pal/"brother" since their time together in foster care; Jamie's wife; that couple's friends; and their little girl, Russell's goddaughter -- ducks out early from a Friday night family get-together, claiming the need to rest up for work (he's a lifeguard at the local public pool) the next day. But Russell's welcoming, accepting, not entirely comfortable family situation falls short of completing him, and he has found himself, understandably, restless and in need of an atmosphere more stimulating and directly relevant to him and his physical and emotional needs. (It apparently helps him to get high before going to, and get drunk during, these family gatherings, which are warm, pleasant, and enjoyable enough, but which he doesn't entirely fit into; one of the film's strongest points is the way that it subtly explores, from different points of view, the multiple, gray-area comfort zones one traverses when one is gay and must move between diverse, mixed, jumbled heterosexual and gay milieux, each with their own unspoken rules and boundaries.) Russell stops in to a meat-marketish gay bar called Propaganda for more than a few drinks to unwind; it's here that he first spots from afar the evidently aloof Glen.

When we cut to Russell's flat the next morning, we fully expect that he will be waking up next to the overly-enthusiastic disco guy with whom we last saw him dancing generously but halfheartedly, but instead it's the admired-but-unobtainable Glen, who rather egotistically claims to have "rescued" Russell from making a drunken mistake the prior evening. The two lounge and have coffee in a sort of belated afterglow; Russell, shy and reticent, is unwillingly talked into participating in the much more forward Glen's nebulous "project," for which the aspiring artist tape-records the sexual recollections of his liaisons for inclusion in some future gallery presentation. (We later learn that Russell has his own, much more private and non-interactive method of similarly logging his sexual encounters for some kind of posterity.) Though this morning-after conversation affords some revelations about the two characters, their different conceptions of and comfort levels with their sexuality, their disparate experiences and ways of defending themselves against disappointment and pain, it leads to nothing more than an amiable goodbye; the two obviously don't expect to see each other again.

What follows is a slow, halting mating dance familiar, in one way or another, to any two people who have ever fallen in love: A self-protectively indifferent text from Glen leads to an unexpected after-work meetup, an actual "date" that neither young man would yet dare to identify as such. Russell takes Glen back to his flat on his bike, this time more for conversation than sex; there is a long, captivatingly well-played dialogue scene in which the two get to know each other through various stages of flirtation and contention as they begin to realize their feelings and their very different ways of handling them. The wrench, revealed not too long thereafter, is that the apparently egotistical, haughty Glen (it may have been bluff, but he has informed Russell that he went home with him because his first choice was already taken) has several better reasons to protect himself from falling in love than we or Russell might suspect, not least of which is that he's off to America in two days to pursue a two-year contemporary-art course. Russell is invited by Glen, again in a come-if-you-like way meant to disguise his sincere wish to see Russell again, to his going-away party; when he actually comes, Glen beats a hasty retreat with him, which takes the two on an impromptu, proper evening date topped off by a celebratory bit of going-away cocaine and a resultant much more revealing interaction between the two, where their feelings -- about each other, about what it is to be gay and to be in love and to be in a relationship -- do finally emerge, sharp and conflicted and tender. Glen doesn't do boyfriends and he doesn't do goodbyes, but if Russell can't be the former, his feelings for Glen compel him (with the additional prodding and logistical help of Jamie, who turns out to really be the "brother" Russell has painted him as) to at least insist on the unwanted goodbye. He and Glen part, for good, on the train platform; it's a fraught, tense, tear-eliciting scene that puts them both at risk for all kinds of vulnerability and embarrassment, the very things both of them have dreaded and tried hard to protect themselves from. But they finally succumb to the pain and joy of openly showing their aborted but real attachment and consequent grief (in a concluding moment, done magnificently by Haigh and the actors, that's suffused with as much grace and gravity as emotional nakedness), and it's as cathartic as it is heartbreaking, an unhappy ending that invites and earns an emotional response far beyond and much more complex than either our happiness over their allowing themselves a moment of unfettered feeling or our crushing disappointment that these two soulmates cannot, finally, be together.

But of course a script is only ever a blueprint, probably moreso in a film like this one, which relies so heavily on the near-real-time playing out of its moments to make its impact. What brings Haigh's sincerely bittersweet, exuberant, never naïve or flippant sensibility to life is the images, montage, and characterizations we ultimately see before us, and all that responsiveness to how each word and gesture feels between two new lovers is there in the visual texture created by Haigh, who is also credited as editor (having started his work as a filmmaker in that capacity, assistant-editing films from Black Hawk Down to Mister Lonely), and his excellent director of photography, Urszula Pontikos. These two artists, along with the supremely natural Cullen and New (who, it would seem, enhanced the flow of at least some of Haigh's dialogue through their own ideas, suggestions, and improv), are entirely up to the very aware, minutely observed approach required by Russell and Glen's story: Pontikos's camera is the third partner in a well-choreographed 90-minute waltz done by the hearts of these two young men, bringing them to an almost too-close forefront via close-up/very shallow focus in some instances, and in others setting them against cold, indifferent, even inhospitable public spaces in more deep-focused exteriors. The emotional temperature of the mise-en-scène is set to just the right point by Pontikos's lighting choices (naturalistic, somewhat glowing when possible, and on the warmer side) and framing (she always seems to be giving the characters and their environs just the right amount of space while never creating any distance that could put us at an emotional remove), along with production designer Sarah Finlay's sense for all the colorfulness within Russell and Glen's often grayly uniform urban backdrop, creating a world whose look and feel occupy a striking but comfortable medium between a vérité approach that wants to see everything exactly as it is, and a more subjective view that reflects, through newly-noticed light and color, the pleasure of falling in love.

All of the film's elements gel harmoniously, boldly charting and adeptly following a course that steers clear of either grit or whimsy, with Russell and Glen's too-brief two-day encounter playing out at a slight but significant remove from strict documentary realism, as if their story is already something fondly, sadly, romantically remembered. It's as if we're looking from the inside at a quiet moment when one or both of them can close their eyes and revisit the memory of that weekend for one more luxuriant, tremendously happy and unbearably sad unspooling of their own most honest, intimate, cherished and unembarrassed impressions of that resonant, imperishable time when their lives overlapped, with its resultant pure connection and great sense of loss upon parting. Weekend gives us full access to that almost intrusively personal feeling, reminding us in a most tangible, overwhelming way that the cinema has a power like no other medium to replicate all those reverberant, ineffable specifics -- inexpressible through any other means than images that move, speak, and play out in time -- of which memories and dreams are made.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The film's AVC-MPEG4, 1080p transfer, preserving the original widescreen theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, is very well-done, practically immaculate; as is so often the case with films shot on high-definition digital video, the transition to digital home-video media is smoother and less obstructed than the trickier business of transferring film. There were a couple of random microseconds where I thought I detected a slight bit of edge enhancement, but those were so fleeting and near-invisible, I may have been overscrutinizing and imagining things; otherwise, the picture is brilliantly vivid, colors and blacks solid, skin tones natural, and no artifacting or visual flaws are to be seen anywhere.

Sound:The disc's Dolby Digital 2.0 surround track is rendered extremely well; I'd venture to say that the film sounds more layered and balanced here, or at least equally so, than it did when I saw it on the big screen. Dialogue is rich, full, and sharp (some non-UK English-speakers unused to adjusting for British accents may want to use the subtitles, though I doubt most people will need them), soundscapes and ambient noise beautifully immediate and nuanced; for one example, the impressiveness of sonic fidelity and clarity is particularly noticeable and nice in a scene depicting Russell at the public pool on lifeguard duty, which makes one's living room redolent with that particular, cavernous swimming-pool type of sound.

Extras:--"Andrew Haigh's Weekend," a half-hour program created specifically for this release, in which Haigh, New, Cullen, Pontikos, and producer Tristan Goligher recollect and discuss, among other things, their particular processes and impressions in their respective capacities; the evolution of Weekend from conception to script to financing and all the way up through its realization; and the thought and decisions that go into making a film that is specifically and honestly about two gay men without making a "gay film" (i.e., one that presumes only to appeal to a gay audience -- as Haigh says, he wants everybody to see this film, and it's worth everyone seeing, too). Haigh is as thoughtful and modest as they come, the actors are remarkably forthright and revealing about their experiences, and this is on the whole a fine behind-the-scenes remembrance and rearview pondering on the fine work these people have done.

--"Andrew Haigh on the sex scenes in Weekend": The director discusses his approach to and ideas behind the sometimes elided, sometimes languorously, explicitly erotic sexual encounters depicted in the film, with particular attention to his considerations of how same-sex sexuality can be (and often is) misrepresented and how one might be able to avoid that. Haigh also explicates the sex scenes' carefully weighed and selected contribution to the film's realist aesthetic, and to the development of its characters and the tentative romance between them.

--Ten minutes comprising videotaped audition footage of Cullen and New playing out two pivotal scenes of interaction from the film, each followed by the version of the scene as it appears in the completed film -- a great insight into the evolution performances and script can (and often should) go through as a film is pulled from the womb of imagination and out into the energized, collaborative honing stages of actual preparation and shooting.

--"Chris New's footage,", eight minutes of candid, often revealing on-set work and discussion captured by a video camera brought along to the shoot by New.

--A photo slideshow featuring the work of Irish photography team Quinnford & Scout, whose casually, playfully, and quite beautifully homoerotic photos, whose lighting and framing lend them an undertow of melancholy, were an inspiration to Haigh in creating Weekend, and who were subsequently hired as the film's still photographers, as well as to help the actors develop their characters and their relationship by creating moments between them not seen in the film (some tenderly sensuous, evocative examples from which have been used prominently as cover/packaging artwork for this home video release). Featuring narration by the photographers, who discuss their own artistic origins/processes and how they came to be involved in Weekend.

--Two short films by Haigh, 2003's Cahuenga Blvd. (6 min.) and 2009's Five Miles Out (18 min.), each of which show a much more tentative, in-development cinematic vision (many confident and well-done touches that don't quite amass together into the kind of power Haigh achieves in Weekend), but prefigure it strongly in their stories and themes, which in both films, disparate as they are, have to do with vitally deep connection and inevitable separation between two characters (in Cahuenga Blvd., a before-parting romantic fling between a young man and an Austrian woman due back home; in Five Miles Out between a teenaged girl with a complicated life and the brave/foolish boy she meets on a restive seaside holiday).

--The film's U.S. theatrical trailer, which is a fairly nice representation/boiling-down of the film for marketing purposes whose only obnoxious touch (in a world where previews are more often than not much more annoying and less trustworthy than this one) is a bit of superimposed, ill-fitting, sappy pop music never once heard in the film.

--A booklet featuring an admiring, very observant and astute essay on the film by critic Dennis Lim.

It's hard to say whether writer/director Andrew Haigh has, with his wonderful realist romance Weekend, either done the best, most effortless-seeming job ever of handling the unfair burden shouldered by any film depicting attraction, sex, romance, and/or love between two men, or if he's just blithely, insouciantly, exhilaratingly dismissed all the excess baggage under which so many gay-themed independent films (Jeffrey, The Broken Hearts Club, et al.) have rather awkwardly tottered. Regardless, the film casts an undeniable spell, its part-expressionistic, part-documentary-realist aesthetic gracefully and acutely capturing human longing, desire, defensiveness, vulnerability, joy, and pain -- in this case experienced by two principal characters, Russell and Glen, who happen to be homosexual humans -- in a way so direct, tender, astute, and often flat-out, dead-on gorgeous that only the most irredeemably gay-squeamish viewer would think to pigeonhole or bracket off the complexities of experience and feeling it depicts into a separate subcategory. That's not to say that Weekend is even remotely an instructional or obsequious act of gay-lib apologetics, one of those works whose primary aim is to meekly remind viewers that gays are people, too; it takes at least some of Russell and Glen's liberation, and all of their humanity, for granted, and instead negotiates, without a trace of pedantry or preachiness, all the more subtle, niggling trouble spots of being gay (and single) in the 2010s.

It is, in fact, its clear-eyed, unapologetic quality -- its forthright yet entirely unforced depiction of same-sex sexuality and its sweet, all-too-rare acknowledgment of its protagonists as rather flawed people trying and often failing to strike a healthy balance between strength and vulnerability, rigid order and free-for-all chaos -- that makes Weekend and its central couple something so compelling, so down-to-earth and recognizable on a moment-by-moment basis. The film easily earns a spot in a contemporary lineage of intimate, modestly contoured, but powerfully moving "couple" films whose duos are deeply connected but bound, sadly, to part -- a romantic-dramatic subgenre exemplified by Before Sunrise and Lost in Translation -- and it's tempting to shorthand it as "the gay Lost in Translation" or what have you. But that apparent compliment wouldn't quite do it justice; Weekend is not just an "alternative" version or self-consciously gay-themed retread of anything else, but a film that becomes, entirely on its own terms, the true, unqualified equal of any heterosexual analogue one could name -- an achievement, pulled off with seeming nonchalance, that's very heartening and almost utopian, at least in the context of cinematic storytelling, leveling the field between sexual orientations absolutely and with no sign of strain. Beyond that, utopian might seem an incongruous word; the film's story and style tend to realism, with both feet planted firmly on the ground, and nothing in it is over-idealized, overdramatized, or mere wishful thinking. But with the skilled, subtle sensitivity, discernment, and ingenuity of Haigh's storytelling; its unfettered tone and attitude; and its calmly open, intelligent, expansive, and generous understanding of people, love, and sex, Weekend does point toward a potentially more equitable, less hung-up future toward which the non-cinematic world is also, one hopes, slowly but surely headed. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||