| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

New Leaf, A

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials and a prior review of the Blu-ray by DVD Savant, not the Blu-ray disc under review.

Elaine May is goofy in a way so natural and effortless, it makes most other goofiness look contrived or superimposed by comparison. As delightfully illustrated by her 1971 film A New Leaf (her screenwriting/directorial feature-film debut), for May, there's no line cordoning off the slightly surreal from the real, the eccentric from the "normal," or the goofy from the buttoned-down/humdrum; it can and does all jumble together inextricably into a sort of sweet chaos that can equally encompass, as it does so refreshingly in A New Leaf, the mundane and the soap-operatic, the angelically clueless and the defensively mean, murderous greed and unexpected love. Like Woody Allen, the onetime feminine half of the formidable Mike Nichols/Elaine May comic diad has an immediately recognizable, odd, pleasantly intriguing persona in which the lines between the actress, the person, and the filmmaker are not really discernible. Her voice is almost but not quite baby-like (a little too much earthiness and lurking intelligence for a Marilyn thing), her physical presence utterly self-deprecating but cheerfully incapable of humiliation; she's like some sort of humanoid alien who looks, thinks, and feels just like us earthlings, but sees our world and expresses her observations in a way that, while recognizable, is just a little bit charmingly off. Which is to say, there is an entire Elaine May sensibility, a quietly and good-naturedly fascinated way of responding to the world that's made up of odd proportions of sweet and sour, fizzy and flat, and that sensibility is refracted delightfully throughout her rambling, sort of messy, palpably joyous and generous first movie, in which the oddest, leas likely pair of lovebirds sing to each other in a register that, as a true surprise, finally comes to make sense and sound strangely sweet between them, regardless of the extremely shaky beginnings of their song or the displeasure of any judgmental listener who might not get it.

Each of A New Leaf's protagonists is clueless in their own way, but, though "sweet" applies from the moment we first meet Henrietta Lowell, the ridiculously klutzy heiress/botanist beautifully underplayed by May (yes, she proves you can underplay what might seem to cry out for slapstick to comedically rewarding effect), it takes until the film's final moments to make out the unearthing of any such quality in the crusty Henry Graham (Walter Matthau). Harry is an overgrown poor little rich boy whose calcified self-involvement, self-pity, self-delusion, arrogance, and snobbery we are familiarized with by the film's first third, wherein one more very large bounced check forces his lawyer/accountant to try to get through Henry's head what most of us poor working slobs know without having to be told: You can't spend more than you bring in without finding yourself in arrears, and it's because the Ferrari-driving, horse-riding, country-club-frequenting Henry has for years insisted on spending $200,000 annually on an income of $90,000 that his checks are bouncing. Once it finally somehow penetrates Henry's brain that he's flat broke (after a prolonged, confused, and hilarious back-and-forth between him and his exasperated attorney) and he realizes he's not only poor but unemployable, he shuffles around Manhattan's tony Upper East Side, where he's gotten used to living among the very well-to-do: He passes through his stomping grounds in a lugubrious, martyred daze, sadly saying goodbye to his neighborhood and making maitres-d and boutique owners wonder at the odd, showily brave-faced way he dreamily floats into their high-end businesses for "one last look" before wandering away again, aloft on his own private cloud of drama-queen haze. (Matthau, whether inspired by May's direction or her ingeniously laconic script, which the director adapted from Jack Ritchie's short story "The Green Heart," reaches his golden mean in this picture; he plays Henry as always and forever put-upon and put out, but never chews the scenery.)

Fortunately for Henry, his ultra-competent, somehow simultaneously deferent and snippy manservant, Harold (George Rose), who's half faux-British decorum and half ballsy/outspoken New Yorker (Rose has some wonderfully funny moments), has on the tip of his tongue a simple way to preserve his employer and his own position: Find a wealthy woman and marry her. The idea of marriage doesn't in any way suit the perpetually petulant Henry, but it is the only way, so after coming up with his own additional twist -- find an heiress with few enough attachments that he can conveniently murder her and reattain his ideal situation of filthy wealth and absence of ball and chain -- he offers everything he has left in the world as collateral to the uncle who very reluctantly raised him in exchange for an immediate $50,000 infusion to help keep up appearances in the short term as he goes courting/fortune-hunting. (James Coco, in his very funny exchange with Matthau, plays the not-very-avuncular Uncle Harry like some roly-poly, even more gleefully rich and contemptuous version of Mr. Burns from The Simpsons). Henry's search for such a bachelorette is fruitless until one day, as the slavering Uncle Harry's strict deadline draws too near for comfort and Henry is distractedly dropping in on an upper-crust society gathering, he spots Henrietta trying (and, through her endemic clumsiness, failing) to remain unobtrusive by sipping her tea in a corner. By the end of the scene, heiress and valuable carpet will be soaked in the tea that should by all rights have remained in her cup, Henry will have seen his opportunity and jumped to Henrietta's defense when the carpet's owner attacks her, and these newly kindred spirits will have been dismissed like Adam and Eve from the sedate, well-appointed, paradisiac playground of the elites.

A whirlwind romance, marriage, and honeymoon ensue, despite the overwrought protestations and attempted interference (more very funny bits) of Henrietta's leeching, scheming attorney, McPherson (Jack Weston), who's long had his own designs on marrying her for money and is the ringleader of her band of freeloading "servants" (a situation put to a swift end by Henry, who obviously has his own interest in the household and its budget). Henry finds Henrietta's geeky obsession with her decidedly unsexy field, her needing to be swept for crumbs after every meal, and her total lack of social grace or taste a turn-off and an annoyance, but he's determined to stick it out right up until the moment he can discreetly off her (an opportunity provided by a botanical field trip way out into the isolated woods and lakes for which wife invites husband along, with a hysterical prologue containing glimpses of Henry's daydream visions featuring Henrietta luckily being besieged and carried off by movie-style Indians, or mauled by a bear). But something starts to happen from the moment Henrietta discovers a new species of fern while they're on their honeymoon, touchingly naming it after the husband she encourages and supports at every turn and sincerely, if delusionally, loves -- something May pulls of the neat trick of never over-hinting at, something that doesn't seem at all certain to mean anything until the very end: For the first time in his life, and in the most unwelcome situation of having someone so dependent on him that she can't even put on her nightgown correctly without his help, Henry begins to find himself...useful and necessary. There is, thankfully, no big, ruinous scene of redemption (this is not at all that kind of movie), but suffice it to say that by the end of the film, the sweet love of a rich, brilliant, infernally clumsy woman has upgraded Henry Graham from money-grubbing potential murderer to curmudgeonly potential history teacher.

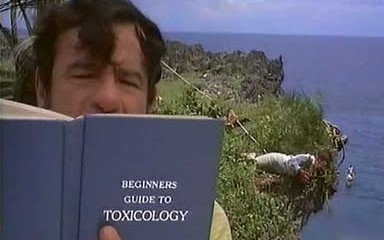

In the meantime, May's unassuming style, which makes the film look and feel as if it's being made up as it goes along, invented by the skin of its teeth, is much more an asset than the drawback it would be in a more tightly scripted, plot-heavy work, and an approach that has its analogues here in the bright, chipper, somewhat (but not too) crude color cinematography of Gayne Rescher (A Face in the Crowd, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan) and the jauntily overblown melodies and tweeting birds in Neal Hefti's original score. (May has an odd, casually gifted intuition for the framing and mise-en-scène of comedy, too; for just one example, there's a great laugh to be had in a deep-focus frame of which half is taken up by Henrietta fumbling in the background with her ferns, with Henry intently reading a toxicology handbook in the very immediate foreground as he studiously contemplates how best to poison her.) The film's rhythm is uneven at times, but so, without a doubt, is that of the comfortably, confidently unhinged and scatterbrained Henrietta/May, so what might seem erratic in a film that was more beholden to the usual virtues of linearity, focus, and consistency doesn't really come off as a problem here, but more like an incidental virtue, just one more natural quirk -- a function of May's wide-eyed inquisitiveness toward the foibles of anyone or any situation whose surface she cares to scratch. The visual attributes are equally haphazard; there is certainly no grand visual design, but the way the film fumbles along, sometimes handheld, sometimes shot in a simple, straightforwardly utilitarian way, sometimes even surprisingly beautiful (the final image, with its unique natural lighting and shift in focus, is striking, but it's fitting that such beauty would come at the conclusion and not be present throughout, as if the shambolic lives and accompanying on-the-fly style of the film have finally reached a moment of transcendence) allows for a spontaneous, often half-improvised feel that May's subsequent, unfairly small body of work (from Mikey and Nicky to the career-destroying Ishtar) has surely shown to be intentional -- her actual, authentic, and personal style, for better or worse flowing without much mediation from her own unique vision.

A New Leaf is an impressive debut that has no blatant signifiers of its impressiveness, just a trueness to itself that's striking for how genuinely unfettered, how assuredly and authentically eccentric it is -- the way nothing in the film feels like a "punchline" but incidental, uncontrived and unforced (no quirk has to be worn on the sleeve; it's all woven seamlessly into the entire garment). It may look like the hapless backing into the auteurist spotlight of a filmmaker whose apparent befuddlement precludes any smooth symmetry or bravura shows of conventional competence, but that's all okay. It's for the best, actually, because the resulting shoulder-shrugging openness carries with it all the pleasures of a very happy, unpretentious, spontaneously unfolding accident -- joyous, ramshackle chaos under haphazard, unpredictable degrees of control. A New Leaf is a very funny, very endearing film whose clumsiness, like that of its odd, appealingly unaffected heroine, magically becomes its own reward.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Presenting the film at a widescreen aspect ratio of 1.78:1, the AVC/MPEG4, 1080p transfer is very nice overall. The warm tones of the film's color (typical, to my eyes, of much late '60s/early '70s film stock) comes through nicely, and everything looks natural and film-like, with zero instances of aliasing or edge enhancement. Some spots of print wear (debris, crackles, and lines on the surface) show up here and there, but there's nothing distracting, and the use of DNR (digital noise reduction) has been kept judiciously balanced throughout, with most scenes still retaining enough celluloid texture to keep your home viewing of A New Leaf close to the cinema experience.

Sound:No distortion or imbalance whatsoever are present to mar the film's original mono sound as conveyed through the disc's DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 soundtrack; all dialogue, music, and ambient sounds come through clear and strong.

Extras:None.

A New Leaf is what you might call a homely comedy, but you'd mean it as a compliment; its relaxed, ramshackle feel is wonderfully apt for its story of two hapless people -- she through her nearsighted befuddlement, he through his blind avariciousness -- who meet under contrived and mercenary circumstances but, by the end of the movie, really do seem meant for each other. The film's innocently meandering quality also beautifully facilitates Elaine May's very, very particular comic genius, all drollery and slightly skewed observation that always seems off the cuff and entirely unforced, making for perhaps the most genuine, "organic" brand of quirkiness ever brought forth via celluloid. The film is gentle and modest, but remarkably so; there are few if any big belly laughs, yet a sense of downplayed goofiness that astutely avoids shrillness (this calm, unharried goofiness is about 180 degrees from the "zany" worst of Terry Gilliam or Tim Burton) permeates its entire world, so that every scene has the unpredictable potential of finding its way into becoming what it is, striking its own naturally precarious and usually very fresh, pleasing balance between comedy and pathos. There's not a trace of the grim, the edgy, or the hardbitten in what turns out to be, after all and most unexpectedly, a love story. Amazingly, however, there's also nary a moment of sentimentality; it's invitingly soft, not mushy. The open-eyed but still optimistic May manages to see, and let us see, the world and the people in it as both irretrievably imperfect and nearly always lovable or at least amusing; the film's authentic benevolence and good humor makes it reflective, in a subtle but strong way, of the good vies still circulating at its epoch (it was released in 1971). There are no hippies or love-ins or beads to be seen in the New York City May gives us, but her insanely graceless, good-hearted, flower-child-in-spirit botanist patiently waits for even future grumpy old man Walter Matthau to get on board with an existence more predicated on curiosity, peace, and love than on greed and avarice. A New Leaf thus becomes one of the most convincing, and certainly among the most enjoyable, examples of good-faith cinematic flora power you're ever likely to come across. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||