| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Rags & Riches Collection: The Films of Mary Pickford

Mary Pickford was both the most famous female Hollywood star of the silent era and, in some respects, an "auteur," though of a different stripe than the Chaplins and Keatons: She didn't direct or write her own pictures (at least not in any official, credited capacity), but she controlled her career in a way that remains rare and impressive for a film actor even today. Pickford cultivated a plucky, young, innocent persona that made her a hugely popular box-office draw, shrewdly handpicking her scenarists and directors to create films of artistic merit that would also showcase her distinctive appeal; she eventually, many decades before what we think of as the "independent film" came to be, even struck an early blow for creative independence and personal vision in the pictures by forming United Artists along with husband Douglas Fairbanks and fellow individualistic filmmakers D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin. In our digital-home-video time, there's been a long, ample, and most welcome wave of superb DVD/Blu-ray releases from the deservedly storied filmographies of Chaplin and Keaton, but so far, Pickford's films (many of them now public-domain) have received mainly cheap, subpar rush jobs from those carelessly, opportunistically exploiting the affordable and easy access to her films. That situation is now well on its way to being remedied with the appearance of Mary Pickford: The Rags and Riches Collection, an authorized Blu-ray release of three films whose preservations, restorations, and current distribution have occurred under the auspices of such conscientious entities as The Library of Congress, Oscilloscope Laboratories (one of the best American independent distributors), Milestone Cinematheque (who also have released Killer of Sheep, Araya, and I Am Cuba), and the Pickford Estate itself. The selection of films is impeccable, each one giving us Pickford at her legendarily appealing, winning, charismatic best, working in tandem with the collaborators (directors, costars, scriptwriters, etc.) she had such a sage instinct for choosing and coming up pictures that let her do what she did best and skillfully create supremely high-quality, creative, inspired exemplars of the art and craft of cinematic storytelling as it was developing, full speed ahead, through the Hollywood system in the 1910s and 1920s.

The first entry in the set's decade-spanning mini-survey is 1917's The Poor Little Rich Girl, directed by Maurice Tourneur (also director of The Blue Bird and father of Cat People director Jacques Tourneur), in which Pickford plays Gwendolyn, a pampered yet oppressed Park Avenue kid whose father is too busy with his business, her mother too busy with social climbing to give her the real love and attention she needs and craves. Gwendolyn longs to play with the regular, poor kids she sees in the street, but servants lurk, yanking blinds shut to imprison her and generally over-regimenting her days and weeks (lessons are stuffy, and she actually asks to go to public school as her 11th birthday present). Whether she's trying to make friends with the playmate presented to her in the form of a spoiled, snotty fellow rich girl, or branching out on her own by inviting the plumber and the organ grinder into the parlor for an impromptu, loud vaudeville performance, much manic (and amusing) chaos ensues. The very same night of her 11th birthday (note that Pickford was 25 when she played Gwendolyn, but yet diminutive stature and genuine ability to emanate childlike physicality make the performance actually, seriously believable), when her parents have neglected her in favor of a chic party downstairs with their society friends, two of the more dubious, mean-spirited servants sedate Gwendolyn so they can have an evening out; when she takes much more of the toxic sedative than her body can handle, a fevered, dream- and nightmare-filled night finds her at the brink of death. The doctor is called, and the near loss of their child shows the parents the error of their ways; daddy will put family above his capitalistic need to become ever more rich, mummy will put her daughter above mingling with the upper crust, and the family will move to the country and be content with the sufficient resources they have, happy and functional together at last.

What might sound like The Poor Little Rich Girl's simple, moralistic tale is told in such a way by Tourneur and the film's technicians that it becomes the most dazzling, creative film of the bunch: the pacing, performances, visual compositions, and mise-en-scène (particularly costumes and set design) are roundly superb, as are the very ornately decorated, storybook-like intertitles, and it's full of wildly creative little touches, such as when the animated words "I-HATE-HER" emerge through the keyhole as Gwendolyn throws a tantrum directed against the other, snobbish, nasty rich girl she's been assigned as a play date, or when the "punishment" of being dressed in boy's clothes becomes a privilege once Gwendolyn catches sight of herself in a full-length mirror and figures she looks awfully darn natty as a boy, not to mention the opportunities for prank-pulling and merrymaking her new disguise grants. The dream sequences, the film's highlight, are Alice-in-Wonderland surrealism, including a poetic passage where Gwendolyn chooses between the cool, eternal rest of death or the sun-dappled frolic of life, and full of literalizing visual effects based on Gwendolyn's misunderstandings of what the grown-ups say (a "two-faced" servant actually has two faces, a nanny who's a "snake in the grass" appears as just that, etc.) -- all surrounded within the frame by a proscenium-arch silhouette that lends the most charming, elegant effect, enhancing the pleasure of the artifice. The Poor Little Rich Girl is the most inventive and free-spirited of The Rags and Riches Collection's three films -- a tale told so imaginatively, with so much visual finesse and fun, it feels as fresh today as it did almost a century ago.

Next comes The Hoodlum, from 1919, directed by Sidney A. Franklin (The Good Earth), a film whose best (and unexpectedly realistic) moments are 180 degrees from the gorgeous flights of fancy boasted by The Poor Little Rich Girl. Pickford is Amy Burke, a spoiled heiress who lives with her tycoon grandfather and thinks nothing of interrupting his important business when, for example, she fears her cat has a fever (there are some adorable sight gags here that will surely delight the millions of us who can't get enough of Internet cat videos). She's all set to sail to Europe with her granddaddy, but when her sociologist father shows back to settle in and write his next book, she decides she'd rather live with her beloved papa, even if that means dwelling in the slums. After an initial culture clash, Amy takes to her new meager, crowded, and noisy surroundings, transforming herself into a tenement heroine by mediating a fight between her building's long-battling Jewish immigrant and Irish immigrant, becoming like a daughter to her father's crusty but gold-hearted cook, and evolving into one of the rowdy but loveable gang of slang-slinging "hoodlums" in the neighborhood (playing dice seems to be about as dangerous as they really get). The real trouble begins when Amy falls for the handsome photographer whose apartment directly faces theirs; little does she know, in the first blush of attraction between them, that he's been wronged by her grandfather's corporation, or that she will wind up breaking into her former, opulent home with him under cover of night to retrieve the ledger that will clear his name. The film plunges headlong and assuredly into Dickensian twist and coincidence with the arrival of a drifter who lives on the third floor and seems to take a special interest in Amy.... With so many misunderstandings and all situations becoming stickier and more complicated with every move she makes, can Amy avoid disgracing herself in the eyes of her loving but disapproving grandfather? Will she get her object of affection out of his sticky situation? Will she, the photographer, and her grandfather learn to forgive and live in peace?

The visuals in The Hoodlum are more subdued than in The Poor Little Rich Girl (though there is a memorable momentary fade to a depicted manifestation of May's pre-enlightenment thought that, in the slums, she's surrounded by swine), but it does boast skilled, dynamic framing, composition, and editing. And then there are the aforementioned peaks, the moments that give the film its surprisingly realist, socially-conscious raison d'être. These come with an interlude during which the previously spoiled-rotten Amy discovers that she and her father live in luxury compared to some of their neighborhood's truly impoverished residents, who are falling sick from hunger and disease in their overcrowded tenements. This affords Franklin the dual chance for some framings that almost journalistically take in unusually gritty subject matter, including close-ups redolent of Walker Evans's or Dorothea Lange's Depression-era photos, which are only enhanced by the reverse-shot emotiveness Pickford proves herself eminently capable of in ways that didn't come up in The Poor Little Rich Girl. The Hoodlum is probably the most conventional entry in this Pickford triptych, but Franklin and Pickford bring it more than enough performative and visual resourcefulness to make it a delight nonetheless, and not just a little resonant due to the actually troubling images it ventures to mix into its exciting, melodramatic story.

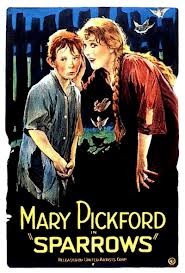

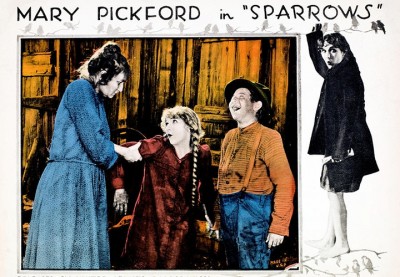

Finally, we skip ahead a number of years ahead for 1926's Sparrows, directed by the prolific William Beaudine (who started off as D.W. Griffith's assistant on Intolerance). The least episodic-feeling of the films in The Rags to Riches Collection, it takes us to an isolated swamp where the villainous Grimes family -- the glum-faced Mr. Grimes, his haggard wife, and their bully of a young son -- runs an ostensible "orphanage" that is in effect more like an internment camp, or worse (Mr. Grimes actually sells one of the children, along with some pigs, to a client). The children are driven mercilessly to their chores, underfed, and mistreated by the awful Grimeses; their only solace is the angelic eldest orphan, Molly (Pickford), who, like Lillian Gish in The Night of the Hunter, is the maternal yet strong protector of the little things life isn't kind to. Among these are the toddler scion of a wealthy family that Grimes has conspired to kidnap for a ransom; Molly falls in love with this child in particular, and after it becomes clear to her that Grimes intends to throw her "baby," cherub cheeks and golden curls and all, into the swamp (which he has implicitly done to other inconvenient residents of his "orphanage") when the ransom doesn't seem to be forthcoming, Molly decides to step things up a notch from her usual strategy of sending S.O.S. notes to the outside world on kites, rounding up her bedraggled gang of orphans for an escape that involves fleeing the monstrous Grimes, his cohorts in crime, and his voracious dog through alligator-infested swamps toward safety and a cruelly ironic justice that will entail a heart-stopping moment when it seems Molly's attachment to her favorite will be shattered, as the child will be taken back into custody by its rightful parents.

There is some sublime, standout craft on display here -- the blue-tinted exteriors of a horrible rainstorm, with the Grimes's cottage and the barn the orphans are forced to stay in represented by miniatures, is especially memorable, as is the literal cinematographic iconography that occurs when, at a moment of despondence, the pure-hearted Molly receives a vision/visitation from her implicit counterpart, Jesus Christ shepherding his vulnerable and endangered flock, a scene for which Beaudine and company create a technically sophisticated, aesthetically ravishing holy-card composition that glows and transports regardless of whether the viewer takes such religious images literally or metaphorically. But, salient moments of film artistry and all, Sparrows ultimately represents the most well-balanced, mature, "classical" entry in Rags and Riches; it's been cited as Pickford's finest picture, and it certainly works best among these three movies as a bridge between the looser, less narratively stable, more episodic silent-era norms and the rules of finer integration -- dramatic, thematic, tonal, and character consistency from start to finish, parallel through-lines in the film that complement each other throughout and resolve themselves in the end -- that the dream factory would continue to perfect through its coming Golden Age, to which the finely honed, thrilling, and touching Sparrows definitely stands as an accomplished precursor.

If you haven't yet discovered for yourself why, once upon a time, Pickford was America's sweetheart and biggest movie star -- a subject of endless fascination and coverage, whether on film or in her private life -- this nifty compendium offers up some of the best, most enjoyable ways to witness and confirm her appeal for yourself. Moreover, while Pickford had her image to uphold (never playing anything close to a villain, for one thing) and the stories between these films do have their overlaps and similarities, their styles are so disparate that they can be said to offer not just an excellent overview of how Pickford's visage shone repeatedly and enduringly from the silver screen directly into a nation's heart, but also an array of silent-film stylistic approaches and techniques, ranging from the skillfully conventional to the deliriously unique and eccentric, pioneered and developed over several pre-talkies decades, that makes the experience gratifying in a way that goes beyond the numerous pleasures of the films and their passionately told stories to make the teeming, wide-ranging artistic diversity of movie history come alive, too. One hopes that, when it comes to prospects for further access to Pickford's long, prolific career through high-quality, officially sanctioned home-video editions like The Rags and Riches Collection, this is just the first part of some long-term, completist project that will eventually make Pickford's entire output available, with the aim of keeping her important cinematic legacy as immediate, alive, and well-known as it deserves to be. In the meantime, this concise, delightful compilation gives us a generous sampling to tide us over -- one that most true-blue cinephiles, especially the devoted-silent-movie-buff subgenre, are bound to find irresistible.

THE BLU-RAY DISCS:

Each of the films contained in Mary Pickford: The Rags and Riches Collection is presented at its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1 via AVC/MPEG-4, 1080p transfers that range from good to very good in picture quality, considering the age of the films (all have had preservation and restoration work done, by the Library of Congress on at least two of the three). None of these, of course, look "pristine" as they've been preserved, and they all have many noticeable scratches, flicker, pops, and other signs of print wear. (There is also an odd intertitle effect on The Hoodlum, where each intertitle appears to be "paused" and become static before cutting to the subsequent scene; I'm guessing this is due to some manipulation necessitated by the restorers and preparers of this home-video edition trying to assure the correct frame-rate -- about which there is some apparent controversy, but which looked fine to my eyes.) However, good celluloid texture has been retained for the most part (no overeager digital noise reduction), the color of the films' tinting looks nice and vivid, and there is nothing here so distracting as to render Pickford's adventures any less compulsively watchable.

Sound:Each silent film is accompanied by a newly-composed orchestral score meant to emulate the musical accompaniment of the era, all presented as PCM 2.0 stereo soundtracks that sound clear, rich, and resonant, with no audio flaws whatsoever.

Extras:Appearing on each disc are the "kid-friendly bonus features" touted on the cover, including a narration option (in which not just the intertitles but explanations of each bit of action is read out in the way one would read a storybook to a child) and some rankly cheesy introductions and epilogues featuring a contemporary "grandpa" with Pickford films and projection apparatus in the attic and a bunch of pre-teen/early-adolescent kids, apparently borrowed from subpar sitcoms, who show up and become his captive audience. However silly these are (they were apparently concocted by someone, somewhere who believes that "today's kids" can be signified with backward baseball caps and the embarrassing overuse of the words "awesome" and "sweet"), they actually do relay good, basic, interesting information about silent-era cinema and might make a reasonably convincing introduction for children of approximately eight or under (or whatever age credulousness stops and a child can see through the bald attempt to pander.)

Extras for The Poor Little Rich Girl include:

--"Dailies from Home Movies at Pickfair" (8 min.), in which Pickford and husband, fellow star Douglas Fairbanks, cavort at their compound with their future United Artists cofounder Charlie Chaplin, mugging and goofing and generally having a good time in front of the camera.

--Feature-length commentary with Scott Eyman, author of Mary Pickford: From Here to Hollywood. Eyman offers a detailed rundown of Pickford's personal and career bios, going into the discrepancy between her public image as a sweet, innocent, guileless girl and strong, self-made, powerful star she actually was, as well as the particular narrative and, especially, stylistic details of The Poor Little Rich Girl that elevated it aesthetically above what she'd done before and secured her her highest place yet in the firmament of motion picture actors.

Extras for The Hoodlum are:

--Ramona (1910, 17 min.), a Biograph short with Pickford as a Spanish-American girl who tragically falls in forbidden love with an Indian, resulting in the destruction of his village and their exile at the hands of the white settlers.

Extras for Sparrows include:

--The film's original theatrical trailer (a nice, relatively rare insight into the way films were promoted in the late silent era).

--Four minutes of outtakes that consist of attempts at an alternate scene to the one in which Jesus Christ appears in the protagonist's dream; in this version, it's an angel that appears to her. (An introductory title suggests this may have been intended for versions distributed to non-Christian-majority markets, though this has never been confirmed.)

--Feature audio commentary with silent film experts Jeffrey Vance (who has also contributed to DVD/Blu-ray editions of The Gold Rush and Modern Times) and Tony Maietta, who share from their abundance of joint knowledge on Pickford, her films and their production, and the gamut of silent pictures in general.

--"The Mary Louise Miller Story" (16 min.) profiles the career of the child actor Mary Louise Miller, who plays the most precious of all of the Sparrows' children and played in a number of other silents as an infant and toddler. With much footage, many stills, and a present-day interview with Miller's granddaughter.

A delightful, career-spanning sampler of silent-film superstar Mary Pickford's work, The Rags and Riches Collection showcases not only the diminutive, sprightly Pickford's charming pluck and magnetic emotiveness, but also the work of her directors, who make each film distinctive, with its own sensibility and its own onscreen world, despite the common factor of Pickford's trademark persona. From the surreal, beautifully inventive Alice-down-the-rabbit-hole dream-fantasy of The Poor Little Rich Girl to the Dickensian convolutions of The Hoodlum to the alternating tempestuous horror and beatific saintliness of Sparrows, we get Pickford in various incarnations, settings, and stories that amply demonstrate her legendary ability to choose the best vehicles for her particular talents and the instantly recognizable persona that made her the biggest female presence of the silent-film era -- a pretty, youthful gamine with a boundless energy and an instinct for performance (not to mention the Tinseltown power, popularity, and independence) to rival those of Chaplin. The Poor Little Rich Girl was my personal favorite of the lot, as it struck me as the most adventurous and original, but all three of these pictures are immensely entertaining, nicely to superbly crafted, and ebullient efforts across the board, perfectly demonstrating what an "A" picture looked like in the silent era. The historical and artistic vitality, along with the sheer, compulsively watchable pleasure, of the pictures themselves, in combination with the concise, three-in-one Pickford introduction/overview offered by the set and the quality of the films' restoration and presentation, make The Rags and Riches Collection a shoo-in for a prominent spot in the collection of both aficionados and anyone with even a marginal or beginner's interest in the classics of the silent period. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||