| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

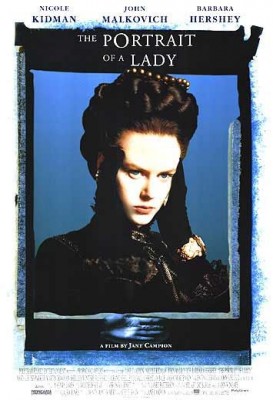

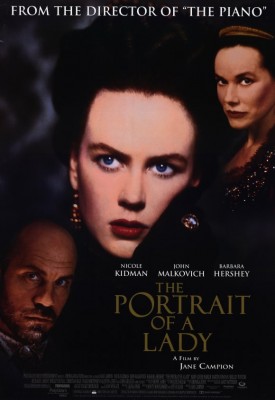

Portrait Of A Lady, The

Please Note: The images used here are from promotional material and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

The Portrait of a Lady, the New Zealand director Jane Campion's ambitious 1996 film adaptation of Henry James's 1881 novel (notoriously difficult/rewarding, like all his best work), was supposed to have been a big deal. The director had impressed audiences and critics worldwide with her prior film, 1993's lovely The Piano, and its star, Nicole Kidman, had done the same with an unexpected dark-comic turn in Gus Van Sant's 1995 satire To Die For. The down-under filmmaker and her actress compatriot were thus both coming off of victories, had the rare opportunity to undertake an intimidating project like The Portrait of a Lady, and great things would have seemed to be in store. But the film, though very highly regarded by the most respectable and insightful voices (Amy Taubin and J. Hoberman, for two), was lukewarmly received, a loss-maker at the box office, and generally considered a setback for both director and star. Why? This long-awaited Blu-ray release (after the film's having been shamefully out of print in North America for many years now) gives viewers perhaps scared off by its inexplicably tainted reputation a chance to puzzle over that for themselves, and it really is a head-scratcher. Could the explanation for The Portrait of a Lady's being unjustly marked with the stamp of failure be as simple (and dull) as there being no unambiguous triumph for its heroine, Isabel Archer (Kidman), like there finally was for Holly Hunter's mute pianist in The Piano, with the studio suits' formula of no happy ending = no audience depressingly vindicated? No matter; the film is at least the equal of The Piano, as true to itself as its more upbeat predecessor, despite that integrity translating to markedly less obstacles-overcome reassurance when it comes to being faithful to the spirit of James's story. It is ultimately perhaps an even more exhilarating work; even though we can't be sure Isabel will ever reach the kind of unfortunately rare liberation that Hunter's Ida obtained (at a cost) in The Piano, what's finally so effectively conveyed by The Portrait of a Lady is something more penetrating, troubling, and rich -- neither happy nor unhappy, but suggestive, mysterious, and transcendent.

Isabel Archer is a young, orphaned American living among rich relatives -- a dying elderly uncle played by John Gielgud, a scattered but sharp-tempered aunt (Shelley Winters), and a much younger, tragically afflicted (with consumption) cousin/ally/suitor, Ralph (the fragile/bohemian-looking, cherub-lipped Martin Donovan). Isabel, in hear early twenties, lusts for a freedom she can't even put a name to, resulting in a surface of uncertainty or even ditzy flightiness that belies a strong, white-hot core of brave curiosity and sense of self. This inarticulate but steely resolve of Isabel's, to fully taste life and fulfill all the promise she feels it has to offer, is tested nonstop by the pervasive 19th-century pressure to marry. The very first scene is of a frustrated Isabel rejecting (once more, we infer) the proposal of a suitor, Lord Warburton (Richard E. Grant, How to Get Ahead in Advertising), and Mr. Goodwood (Viggo Mortensen, A Dangerous Method), a fellow American, has followed her far and wide to plead his case with her, to her utter consternation. Cousin Ralph, who loves her more sincerely than anyone, holds back, both because of his condition and because he senses there's something great latent in Isabel, which marriage could only compromise. When the uncle passes away, Isabel is startled to learn that he has left her the bulk of his fortune, transforming her into someone with the means to be as independent, well-traveled, and cultured as she has dreamt; she and her busybody, loudmouthed, bluestocking friend (Mary-Louise Parker, Angels in America, who provides comic relief) are free to take the Continental tour then prescribed to all members of the upper class as essential to one's education.

It is while in Italy that Isabel falls into the trap set by Madame Merle (Barbara Hershey), the wealthy but deeply dissatisfied middle-aged woman she has met at her uncle's country estate. Madame Merle is a picture of Isabel's high standards, thwarted: Just as smart, independent-spirited, and ambitious as her new young friend, she has been brought low and seen her ideals permanently derailed by her long-running involvement with an indolent, imperiously authoritarian expatriate gadabout/sometimes-artist, Mr. Osmond (John Malkovich, perhaps unfairly typecast after Dangerous Liaisons as a satanically sibilant seducer, but nonetheless born to play this role). Madame Merle can't bear to see Isabel have what her life and her time have cruelly robbed from her, and so she practically offers her beautiful friend up to the wily Osmond on a silver platter. This "gentleman" has had practice at insisting, pleading an airtight case, and, yes, overpowering women -- his arguing, browbeating, and bullying tactics are well-honed and quite unlike the sincere, open proposals Isabel has had no difficulty refusing -- and Isabel succumbs, taking a place at the head of the menagerie of cowed females Mr. Osmond keeps in his luxurious Italian digs. This includes a "spinster" sister, Countess Gemini (Shelley Duvall, 3 Women, in what should've been a comeback performance), a silly-seeming woman who proves to be one of Isabel's greatest aids, and his daughter, Pansy (Valentina Cervi, Jane Eyre), whom he has imprisoned in a convent and whom he means to mold into his objectifying vision of a Perfect Young Lady by any means necessary. The Osmonds' marriage is stifled, miserable; everyone in Isabel's life who cares about her, especially the heartbroken Ralph, can see that some vital part of her has been amputated by Mr. Osmond. Eventually and at long last, a dual blow to Isabel at the hands of Osmond -- his forcing Pansy, of whom Isabel is very fond and protective, back into the convent to prevent her from marrying a handsome, devoted suitor (Christian Bale) instead of a "proper," aristocratic marriage, and his cruel insistence that she obey his order to remain with him in Italy rather than visit Ralph on his deathbed back in England -- shakes her from his spell, and she defies the oppressive husband by returning to England, if only temporarily, to pay final tribute to her truest (though always platonic) love. But even there, in mourning and away from her husband, she must still contend with Mr. Goodwood's undying, ever-deepening affections. Whether she stays in England or returns to her husband, will Isabel Archer -- who once expressed that some notion of "freedom," of living life to the fullest, were her reasons for being -- ever rediscover and renew her devotion to taking a path of her own making?

The consistent current that Campion finds running under James's story is a precious spark of choice, autonomy, hope for fulfillment -- all severely challenged, of course, by bluntly sexist Victorian mores and its strict, deeply embedded gender roles -- that passes or reflects itself between the story's women. Madame Merle once had it, but she resentfully, jealously feels the need to extinguish it in Isabel, and when Isabel feels it dying out in her, she tries (and fails) to hand it off to her stepdaughter, quite against her husband's authoritarian, "traditional" will; the faint, uncertain hope at the conclusion is that Isabel might find some way to keep it alive, but that would be against all odds. Campion and her brilliant longtime cinematographer, Stuart Dryburgh, find innovative (and, for some literary purists, "controversial") visual means of cluing us in to this spark, creating an odd yet seamless, remarkably deft balance between period sumptuousness (bulwarked by Campion's well-chosen classical selections and a sweeping, melancholy score by Bram Stoker's Dracula composer Wojciech Kilar) and an immediacy that never once lets things become precious or merely ornate. Some have complained, for example, that James never wrote the erotic reverie, plucked from Isabel's imagination, in which she pictures herself, in the wake of a tender kiss from Mr. Goodwood, being caressed and possibly ravished by both Lord Warburton and her American suitor while her amorous cousin looks on raptly. But erotic desires and appetite, implicitly forbidden to a woman of Isabel Archer's time, place, and station, are one of the most deeply impassioned, natural, obscured parts of the experience of life , and these glimpses of the liberated possibilities Isabel has difficulty even allowing herself to contemplate are certainly implied in James's story; are beautifully, subtly done; and are vital to grasping the film's meaning. Campion's and Dryburgh's roundly fresh, lively mise-en-scène, framings, and lighting are recurrently punctuated in this way, by even bolder un-"period" yet apt touches, e.g., the visual snapshot album of Isabel's Continental travels and falling for Mr. Osmond -- brought to life in a jittery, square-framed, black-and-white silent-film interlude that's eerily artificial and has the unsettling, surrealistic feel of a dream slowly morphing into a nightmare -- and the increasingly off-center, skewed-angle framings (a film-noir device meant to evoke the disorientation and treachery of otherwise pleasant or at least normal physical space and thus recruited very adroitly to Campion's purposes) of the Italian destinations that Isabel visits. Then there's the sparingly but perfectly deployed slo-mo -- a device that can easily be overused or misused -- that adds exactly the right emphasis wherever it appears, such as when, in an expressive two-shot, Isabel catches a glimpse of the purple flowers Pansy clutches (which have been given to the girl out of an unfettered romantic love her stepmother recognizes but has never truly experienced) and, especially, in the film's absolutely haunting, enigmatic ending, in which Isabel races away from the genuine but stifling entreaties of Mr. Goodwood through the gardens and back to the door of her family's home. In this concluding, wordless moment, where all the meaning comes from that slow-motion flight to precisely nowhere, Kidman's and Campion's heroine takes on the gorgeously tragic aspect of a caged bird nobly, futilely fluttering and beating its wings against a cage it has little hope of ever escaping.

Campion's The Portrait of a Lady -- because of the poor terms on which it was received and because it continues to give the lie to its critics by being an extraordinarily incisive, transporting, unforgettable experience that transforms the literary to the cinematic, and the "period" to the engagingly, immediately relevant -- has all the attributes of a lost classic, ripe with the additional pleasures of rediscovery it has to offer on top of its own plentiful innate accomplishments. The film's opening titles themselves -- another "odd" yet just-right choice for what Campion is setting out to do -- seem somehow to allude to this misunderstanding, neglect, forgotten-ness, and suggests that we ignore or misapprehend The Portrait of a Lady at our own peril: Before we see any of the characters or the 19th-century world in which they strive against formidable societal opposition to discover themselves, the credits play out over an utterly anachronistic (in the context of the film's period) black-and-white montage of young, contemporary women frolicking in a park somewhere, dancing and moving loosely, being comfortable, staring down the camera boldly, and otherwise looking, feeling, being "free" -- before the film's title is displayed in close-up, inked in pen on the palm of one of these young ladies' hands, like a mnemonic device, a little reminder not to forget that things were not always thus and that there's no guarantee, in the absence of awareness of the ongoing struggle portrayed so vividly in The Portrait of a Lady, that they will continue to be.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG-4, 1080p transfer is (to cite the title of another Kidman triumph) to die for; aside from some very minor edge enhancement, it's nearly perfect. Whether it's Italian sunshine, a drenching downpour, sumptuous interiors, pastoral exteriors, or English-countryside snowdrifts, all of the film's beautiful colors and lighting are very nicely preserved and presented here. Skin tones all look natural, darks are nice and solid throughout, the image is sharp and clear, and best of all, the tactile/celluloid experience of the film has been carefully retained, with a very healthy amount of grain un-tweaked by digital noise reduction (DNR). An excellent transfer overall.

Sound:The film's DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 soundtrack (with a 2.0 option for those viewing without rear speakers) is equally glorious, with all dialogue and foley/ambient sounds solidly present, immediate, and sonorous. All of the film's score and many classical-music selections are rich and multilayered, and everything is crystal-clear throughout, without a single moment of distortion or imbalance.

Extras:--"Portrait: Jane Campion and The Portrait of a Lady", an hour-long behind-the-scenes documentary on the making of the film that, despite its moments of insight and reflectiveness, is the most truly revealing, nitty-gritty, uncensored on-set look of this sort that I've ever seen, even more raw than Vivian Kubrick's Shining making-of. Here, the full frailty (and consequent difficulty) of the ailing Shelley Winters is revealed, as is the insecurity of actor Richard E. Grant and the fragile, earnest, anguished commitment of Kidman to doing her part justice. There's also the perhaps unsurprising (to anyone who's seen Adaptation, at least) temper and impatience of John Malkovich, whom the documentarians' camera catches boasting, as he lectures Campion about how he hates the interminable waiting for setup/lighting involved in shooting a film, that "I screamed at [Vittorio] Storaro!" (the cinematographer with whom Malkovich worked on Bertolucci's The Sheltering Sky). It's a feast of filmmaking detail for both the serious cinephile and the frivolous gossip-monger in you.

--The film's original theatrical trailer.

It's probably true that Henry James's dense, ambiguous novels can't be "dramatized," but Jane Campion's 1996 adaptation of his The Portrait of a Lady insistently, brilliantly reminds us that the cinema has so much more at its disposal than just "drama," and it proves that it's in the tone and texture, not just in the plot, that the medium can do justice to a literary source, capturing a novel's feeling on its own visual/aural terms. The unspoken quality of James -- the stillness, the opaqueness -- that has for so long impressed and maddened readers thus survives beautifully in its transition to film, with Campion's intelligent, sensitive, astute rendering of Laura Jones's script planting seeds in our hearts and minds that blossom into something explosive as bombs. Campion and Jones fully get the true, ambivalent modernity latent in Henry James; the period detail is exquisite but never a stuffy big-screen antiques shop; and Nicole Kidman, ravishing as conflicted, prismatic heroine Isabel Archer, gets to spar disturbingly with John Malkovich and tenderly with Martin Donovan, all while surrounded by briefer but all-around excellent performances from superb cast that encompasses two great Shelleys (Winters and Duvall), Christian Bale, Viggo Mortensen, and the film's potent secret weapon, Barbara Hershey, as Isabel's sister-under-the-skin, enemy-on-the-surface nemesis. No, The Portrait of a Lady is not in any way The Piano Part II (Campion is stretching herself, exploring further reaches of her complex and expansive feminist thematics here, and succeeding beautifully), but it is a daring, accomplished work that deserved much better reviews and attendance than it initially received. With the arrival of this wonderful-looking and -sounding Blu-ray edition, Campion's excellent, wrongly rejected film can finally receive the long-overdue revisionist assessment it's been awaiting for so long, and we fortunate viewers finally have the chance to give it its rightful place in our collections and glean the richness from its multiple layers on progressively more rewarding second, third, and fourth viewings, and beyond. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||