| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

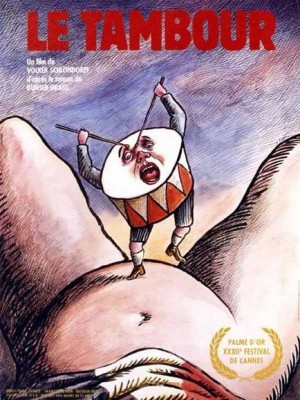

Tin Drum: The Criterion Collection, The

Pity poor Oskar, even though he has only himself to blame. The Polish-German hero/villain/cipher (played by Daniel Bennent) of Volker Schlöndorff's 1979 historical-allegorical epic parable The Tin Drum is a boy who starts out as a blank slate and, in his determination to remain blank at all costs, becomes passively complicit with evil, mistaking blissful ignorance for childlike innocence. Oskar is a character who refuses to grow up, physically speaking; the fact that he's small may be his own fault, but he nevertheless must carry a burden that seems far too heavy -- the weight of world history, the personification of a nation doomed by its own childish refusal to grow up -- on his little child's shoulders. Schlondörff, too -- a very intelligent and skilled German director who, because he could pull off multiple styles but never developed much of a personal signature, stylistically, never quite attained the auteur status bestowed upon his German contemporaries Wenders, Fassbinder, and Herzog -- would seem to have taken an unfair burden upon himself, in the form of a story that would appear to any sane person to be much too much for a feature-length film to tell properly. The Tin Drum is an adaptation of Nobel prizewinning German novelist Günter Grass's huge (literally and metaphorically) 1959 novel-as-distillation of a gullible, complacent, self-deceived and self-satisfied nation's depleted soul and dangerous hubris -- a bold, rightly venerated, intimidatingly far-reaching and accomplished book in which the self-stunted Oskar's story is nothing less than that of Germany itself, through the part of the 20th century that saw its monstrous rise and precipitous fall. The novel is a deep, dark, complicated, not immediately adaptable-seeming story if there ever was one, spun on the page by Grass so that it becomes intricately layered, expansive, bursting with sometimes highly contradictory thoughts and ideas, most of which are tangled right up with the heart of one of the most troubling episodes in 20th century history, Germany's embrace of murderous Nazism. Yet, Grass was capable of making powerful, provocative art out of his fable-like conceit, doing full justice to a fantasy-gripped people's childlike bewilderment at its own destruction without ever coming close to excusing the arrogant madness that they suicidally subscribed to, and Schlöndorff does his source proud, gleaning with great care and sagacity just precisely the right elements -- only the best-suited episodes and their most applicable nuances, no more and no less -- of Grass's gargantuan vision for his always inspired and assured, frequently inventive moving-picture rendition.

The little boy Oskar, born between the two world wars in Danzig, an embattled no-man's-land between Poland and Germany, comes from mixed and tangled roots. He's uncertain whether his heritage is German or Kashubian (a Polish minority ethnic group), because of his mother's (Angela Winkler, star of Schöndorff's 1975 film The Lost Honor of Katharina Blüm) long-running love triangle with her German/Nazi sympathizer lover and eventual husband, Alfred Matzerath (Mario Adorf), and her Kashubian/Polish cousin, Jan Bronski (Daniel Olbrychski, Salt), either of whom could be Oskar's father. (Neither he nor we ever know for sure, which is deeply significant in a tale whose historical/cultural backdrop features a notorious surge of ultra-nationalist/racial-purist pride.) Oskar decides one day, in a fit of pique when confounded and overwhelmed by the grown-up complications, compromises, and hypocrisies all around him, which he can see full well despite the prevarications of the adults in his life (if there's one article of faith that the novel subscribes to uncritically, it's that children see everything, and Schlöndorff wisely uses this as a very effective visual device), that he will simply stop maturing physically, throwing himself down the cellar stairs to give the grown-ups a plausible explanation for the unchanging child's body he's chosen never to let grow. Oskar prefers instead to cling to his little tin drum, from which he's inseparable, and garner attention both positive and negative with his talent for shattering glass with his high-pitched shrieks; he wants the child's privilege of neutrality and self-centeredness, never being bothered by the moral choices and the confrontations with cold reality that no adult can exempt themselves from. But regardless of his anomalous physical state, Oskar and his mother and father(s) form, for a while, a unit that resembles closely enough what would become Germany's ideal "Aryan" family -- a nuclear unit that's idyllic and robust on the surface, but something other than "pure," rather shaky and insecure, at the roots.

Despite his permanent physical prepubescence, Oskar comes of age in many ways just like most boys, developing an interest in girls, getting bullied by the bigger and stronger kids in the neighborhood, etc. -- episodes familiar from lots of coming-of-age stories, except he remains physically a child, which disturbs as he chases, experiments with, and has affairs with girls and eventually forms his own love triangle, along with his father, with the babysitter, Maria (Katharina Talbach, Sophie's Choice), brought in after his mother's death. But that superficial disturbance is a red herring. The deeper problem, we begin to realize, is that non-ideological, seemingly apolitical Oskar is what any typical, ordinary, working German of the Nazi era would look like if their true spirit were made physically manifest: It's an entire people clinging, like Oskar, to the child's privilege, willfully blind and full of placid faith in the fascist authorities because it's easier and less disruptive to their individual, comfortably myopic lives. With no conscious malice, Oskar both takes after and leaves behind his cheerfully, mindlessly patriotic, team-player father by supporting the regime, joining up with a troupe of dwarf traveling players entertaining the Nazis. He does this with no qualms despite his best friend, a Jewish toy-shop proprietor, having been driven to suicide by Nazi persecution; his uncle (father?) Jan being killed by xenophobic Germans as they destroy the non-German, Polish section of Danzig; and his own mother, beset by premonitions of things to come in the guise of happy homemaking and love of Hitler, eventually following the same escape route as the toy seller. The connection between his own existence and the horror of his society is one that Oskar, like any "good German" of the time, fails to make. Despite his popularity among the Nazi troops as an entertainer, he discovers that his own anomalousness places him on the wrong side of Hitler's program and puts him the outs with the local chapter of the Nazi health-and-purity brigade; even then, it takes rock-bottom personal catastrophe resulting from the devastating German defeat that leads Oskar to finally relinquish his tin drum, tellingly at the same moment he relinquishes his beloved, affectionate, but poisonously status quo-seeking father to the soil after he's killed by the Russian troops violently "liberating" Danzig.

What could possibly be the proper tone for this tale of an apparently ordinary Nazi family with its little boy that refuses to grow up? Schlöndorf manages with shocking ease to capture all the layers, from the deadpan-observant to the satirical to the symbolically weighty to the emotionally devastating, sliding smoothly from normality to horror both between and within scenes in such a way that The Tin Drum remains the best illustration of his intuition, skill, and inventiveness as a director. The film is replete with sequences that manage this feat, but two in particular seem to exemplify all of the many things the it's up to: In the first, Oskar, his uncle(?) Jan, his father(?) Alfred, and his mother take a trip to the beach on a holiday, and they create the perfect National-Socialist picture of a good, healthy, decent working family at leisure, stopping during their seaside stroll to chat cheerfully with a fisherman. But the fisherman drags a horse's head out of the sea, oozing and writhing with eels and other seafood that he scoops out of its petrified mouth, Oskar's mother becomes sick (as, likely, do we) at the sight, while his father eagerly accepts the eels and cooks them up at home. The mother's disgusted initial refusal to eat the eels, followed by a 180-degree turn into a grimly determined weeks-long seafood binge, is itself symbolic of her intuitive resistance, then despairing and suicidal succumbing to, the inexorable shift to Nazism in the world around her, including in her own husband and even in herself (she's no protestor, and happily abides the Hitler portrait in their parlor; it's some unconscious part of her that knows something's horribly wrong). In the other most exemplary sequence, a magnificently shot and edited set piece, an open-air Nazi rally loses its pomp and at least the externally visible part of its horror as, spurred on by Oskar's rowdy, dissonant drumming and broken up by a thunderstorm, most of the participants reveal, to the consternation of the true-believer marshal of the big spectacle, their main purpose: to join up with the others and have fun, breaking formation to dance and frolic under the Nazi flags whose actual meaning they remain self-servingly vague on -- a vagueness that Oskar and his family share, and one that, as we all know, kept the German citizenry in a comfy torpor until it was much too late. As Oskar evocatively puts it in voice-over during a panoramic long-shot scene in which we see Danzig burn, the Hitler-besotted Germans, reeling from their post-WWI destitution and reverting to a wannabe-pure state of innocent childlikeness, expected the fuhrer to be Santa Claus. Instead, they got "the gas man."

Employing his enormously talented longtime cinematographer, Igor Luther, Schlöndorff offers up many a visual delight: In addition to the aforementioned seaside postcard revealing its grotesque side, and the majesty-sliding-into-chaos of the Nazi rally, the newsreel flicker/slightly sped-up, silent film-like quality brought out in several scenes (set, appropriately for their style, in the early 20th century, as Oskar relates his lineage beginning with his Kashubian-peasant grandmother) rhymes well with the actual newsreel footage Schlöndorff judiciously employs at the right intervals. Then there's the film's most famous sequence, the very creatively conceived, brilliantly shot scene of Oskar's birth, in which we join him inside the womb and experience, along with him, his emergence out into a cold, dimly lit hospital room. The compositions and framings, with their mix of beautiful period detail and their lived-in immediacy, are always just a little off-kilter, with just enough odd (a)symmetry that the film is consistently able to straddle the line that would divide its historical-epic feel from its surrealist/magical-realist layer, doubling its momentum and impact by gaining the narrative power of both. The special effects are never fancy, just elegantly simple, convincing, and (as, for just one example, at the moment Oskar's shrill shriek shatters hundreds of windows as they reflecting the glow of the sunlight) aesthetically pleasing. From scene to scene, you never know what unpredictable cinematic resources -- lighting, camera movements and film speed, strikingly unexpected and meaningful reframings, etc. -- Schlöndorff will draw upon to make it work (as it nearly always does), which makes for a ride with many and varied enjoyments -- a breathtakingly wide-ranging visual analogue to the director's audacious spanning of multiple narrative facets and themes.

The Tin Drum is, aptly enough in light of its story and themes, by far the "biggest" film Schlöndorff ever did, and as it turned out, Schlöndorff was with the zeitgeist, venturing into this particular kind of bigness at just the right time: Making for a season of unbelievably ambitious, risk-taking, big-budget problematic-history movies, his film was the co-winner in a tie for that year's Palme d'Or at Cannes, the other winner being Coppola's Apocalypse Now (it would later take home a well-deserved Best Foreign Film Oscar); these two films, for all their marked differences (Coppola's is more personal, feverishly obsessive, and passionate, clearly, though now that the dust has cleared, it would seem that Schlöndorff's is by a significant margin the less-muddled, better-realized, more unusual and more artistically successful film), are uncannily connected in their basic impulse and scale of execution, with both the German and the American filmmaker bravely/crazily grappling with a horrifying, never-to-be-resolved episode from their respective nation's recent pasts. The big-canvas quality of the now-classic The Tin Drum hasn't diminished or grown stale with time; it remains fresh and alive through every repeat viewing, its enduring status as a very high achievement (both in Schlöndorff's up-and-down career and in the annals of the always-sticky movie genre that purports to represent history) deriving from its pragmatic, bottomlessly resourceful ability to grapple with the troubling realities of history while accepting the impossibility of boiling them down to anything easily or fully knowable. It plays many roles at once as it makes its difficult but necessary attempt, if not to reconcile or explain, then to at least fully look at, acknowledge, in some way do justice to, the particularly challenging slice of history it takes on, and it takes each of those roles -- documenter, satirizer, eulogizer, scold, repository of a nation's regret and sorrow, warning sign for future times and other places -- to a gratifying level of fruition.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

This 1.66:1 (original theatrical aspect ratio) widescreen transfer of the film is a gigantic step up from the picture quality of the prior DVD release. It's no exaggeration to say that it's to die for: The capabilities of Blu-ray and the ultra-proficient way they're taken advantage of here does wonders for the sharpness, clarity, and sheer accurate conveyance of cinematographer Igor Luther's subdued yet rich color palette, with its higher-than-usual ratio of more muted/dimly-lit scenes apparently posing no problems for the wizards who did this remarkable job of putting the film on Blu-ray. There's not a trace of aliasing, and on the edge-enhancement front, this is one of the best transfers I've seen; you can usually make out at least a little in even the best transfers, but I didn't spot a trace of it here. If any digital noise reduction was used, it's as discrete as can be; the grain and texture throughout is amazingly natural, completely gorgeous. Overall, this is picture quality to die for -- one of the nicest, most conscientious and faithful transfers you'll come across.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround soundtrack (in German with optional English subtitles) replaces the monaural 1.0 and Dolby Digital 5.1 surround tracks available on the prior DVD version, and it sounds absolutely fantastic: Not even little Oskar's screams bump that needle into the red, and the surround is used judiciously, so it never feels like sonic revisionism (though the film was widely released, the 5.1 surround elements are based on an "original" soundtrack, one created for special 70 mm showings of the film during its initial release) -- no intimacy is lost in the quieter scenes, though the dialogue is probably richer and clearer than we've heard it before, and the "bigness" afforded by the high-tech sound is brought into play only when appropriate, such as in the scene of the Nazi rally sliding into chaos, which has every channel going, and the subwoofer noticeably kicking in for the scene's deep kettle drums. Again, it's difficult to imagine a better job, making full use of the best technology available while remaining true to the film's intended tone and feel.

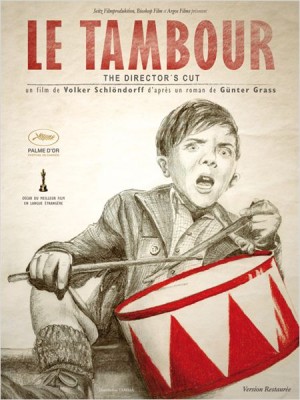

Extras:Judging the supplements on this fantastic-looking re-release of The Tin Drum is somewhat sticky: What we're getting is practically a new film, what with the additional restored 20 minutes to render a true director's cut and the new, thrillingly high quality of the picture throughout, and Criterion isn't at all out of order to have forgone most of the supplements included in their two-disc 2004 DVD version for an all-new batch. The old bonus content not included here was a feature-length audio commentary by Schlöndorff; a handful of deleted scenes (most if not all of them no longer deleted, one presumes, in this longer director's cut), and an isolated-score option in the audio; an onscreen-text script excerpt and still photo gallery. Though the booklet insert for the new edition features an essay on the film by film critic/historian Geoffrey Macnab rather than the old essay by Eric Rentschler, the brief written comment by Günter Grass on the adaptation of his novel remains, as does his Grass's 7-minute reading, excerpted from his novel, of an important scene, though here it appears with the filmed version of the scene in question rather than the musical accompaniment from before. This edition also carries over the handful of TV interviews around the film's release (Bentner and Schlondörff at Cannes, writer Jean-Claude Carrière and actor Mario Adorf on French TV, a French newscast excerpt featuring on-set footage, etc.).

That's a fair number of omissions, but it is a more or less fair trade-off for the new bonus features, all made with the director's cut in mind: A brand-new, almost feature-length (approx. one hour) illustrated documentary interview with director Volker Schlöndorff that covers the entire gamut of the film's conception, preparation, production, reception, and new restoration, along with his own anecdotes (delivered with surprisingly jolly, almost self-effacing humor and candor) from the whole process, digressing here and there into the more general territory of his filmmaking career and his thoughts on cinema. There's also a 20-minute interview on New German Cinema with film scholar Timothy Corrigan, with a particular focus on Schlöndorff, in which the thoughtful and well-spoken Corrigan convincingly explores the roots of New German Cinema, pointing out Schlöndorff's similarities to and differences from his cohorts in the "German New Wave" of the '70s, to a nicely enlightening, knowledgeably contextualizing effect. The only out-and-out missing piece here is the documentary that was included in the 2004 DVD, Gary D. Rhodes's Banned in Oklahoma, which recounted a fascinating (and enraging) U.S. obscenity case/censorship attempt directed at The Tin Drum on home video. In all, the array of extras here is very worthy, and many of the alterations from the prior edition relevant and understandable; the absence of Banned in Oklahoma mostly just means that those who have the 2004 DVD edition will want to hang onto it and double dip for the new Blu, with its vastly improved picture quality.

The Tin Drum is a film that bears an unbelievable literary and world-historical weight on its shoulders, yet it not only manages to nimbly carry that burden, but actually lifts it up to some soaring heights while never losing the gravity inherent in its story. That story is nothing less than the ignoble decline and fall of an entire, proud (if not arrogant) nation and people -- Germany in the early to mid-20th century. Before it became such an astonishingly epochal film (along with its evil twin, Syberberg's roughly contemporaneous Our Hitler, it's one of the understandably very few films to really face head-on the challenge of somehow getting our heads around this huge, complicated, morally incomprehensible and yet all-too-real story -- the Icarus-like fate of one cultivated, "civilized," centuries-old Germany and the dazed, scarred, uncertain, and ashamed beginning of another), The Tin Drum was Nobel prizewinning novelist Günter Grass's magnum opus, the richest, most daring work of postwar German literature, and Grass's erstwhile countryman, filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff -- whose own youth had coincided with Germany's defeat in WWII, and who, after Young Törless and Coup de Grâce, was no stranger to turning intimidatingly renowned novels into movies -- made it the crowning achievement of his own body of work as well. Maybe it was its closeness to the director's own experience, how deeply it struck at the harrowing complexities of the place and time he came from (or, less romantically, just a particular confluence of great collaborators and artistic risks that paid off through effort or luck); whatever the explanation, Schlöndorff's highly skilled, craftsmanlike cinematic intuition was clearly cranked up by this project into its highest, most invigorated and accomplished gear, set alight by Grass's extensive, sardonic parable of Germany as both seen through the eyes of, and represented by, a little boy, Oskar (Daniel Bennent), who refuses to grow, willing himself to remain physically somewhere between toddler and teenager while the rest of the world grows up around him, or at least appears to.

Much as we'd like to believe that it's simple -- Hitler was evil, Germany was wrong and bad, the good guys won, end of story -- Oskar's tale is, while in no way an apologetic for National Socialism's horror, richer, more complicated, and much more incisive than that; it comprises all of Oskar's personal and familial mundaneness and eccentricities, then meshes them into layers and layers of "real" history, allegory, and satire to illustrate just how easy, how recognizable, a slow, casual, complacent slide into fascism was. Schlöndorff and his collaborators (most remarkable and indispensable among whom are co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière and cinematographer Igor Luther) fearlessly and ably bring it all to full, vivid, epic life, gracefully encompassing the decades-spanning, painful growing pains of Oskar's country through his curious but uncomprehending, self-involved child's eyes, always preoccupied with his own everyday life (the film doesn't skimp on the banality of evil, which appears here as Hitler portraits and obligatory Nazi social-climbing while quotidian family life 'n strife goes on as usual, the rancid hatefulness of Hitler's ideology some sort of open secret, always somewhere off in the periphery of one's vision), while simultaneously positing Oskar as a metaphorical figure embodying the puffed-up and grandiose, yet stunted and infantile, interwar Germany itself. Schlöndorff manages to walk the same delicate tightrope, on cinematic-storytelling terms, that Grass did in his book: His film is, amazingly, never belabored, not afraid to spin its tale stylishly and enthusiastically, as light on its feet as its payload is heavier than practically any other historical tale one might choose to tell; at the same time, it's never in danger of trivializing the horrors of Hitler's imperialist regime or the German people's complicity. Schlöndorff knows what Grass knew, and he brings the full strength of that conviction to bear on his remarkable screen version of The Tin Drum: Metaphor can be applied for poor reasons -- pulling punches, disguising uncomfortable realities, and dissembling when it comes to the real heart of the matter -- but it can also allow a deeper, truer understanding of something complex and problematic than any dutiful, straightforward retelling of the facts. It's the latter power with which The Tin Drum is replete, and through which it terrifies, sobers, and moves, all the more so now that it's been expanded back out to the full length of Schlondörff's original vision on this carefully and beautifully produced new Blu-ray version. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||