| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

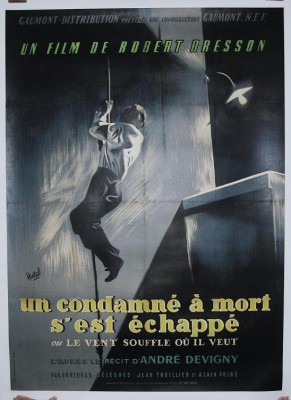

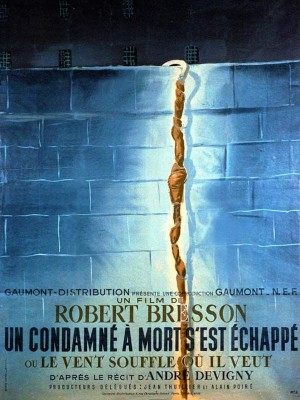

Man Escaped: The Criterion Collection, A

Please Note: The images used here are taken from stills provided by The Criterion Collection and promotional materials, not the Blu-ray edition of the film under review.

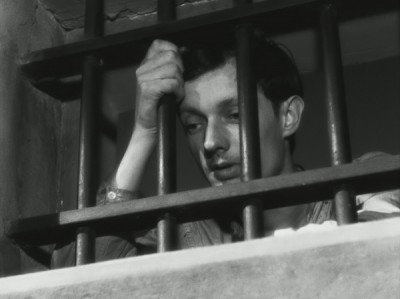

Robert Bresson's 1956 film A Man Escaped is, you could accurately say, a prison-break picture. Its tale of French Resistance fighter Fontaine's (François Leterrier) capture and condemnation by, and escape from, the Nazis during their occupation of France has story elements in common with The Great Escape, Stalag 17, or, to take a nearer example, Jacques Becker's Le Trou. But no story put to celluloid in Bresson's inimitable, painstakingly clear, focused, emotion- and suspense-postponing style could ever resemble, in actual execution, any other, however many times it's been told by a diverse group of filmmakers over the years. The stakes are simply higher, always, for Bresson (who was, it's interesting to note, himself a prisoner of the Germans during the war): His peculiar, self-described blend of atheism and Catholicism permeates his films; there's an obsession, which runs through his entire filmography, with a war between the flesh/earthly concerns/extraneous matters and the spirit/soul/essence of things, with a truce only available through some miraculous transformation. In the case of A Man Escaped, the scenario (taken, and no doubt modified/pruned, from the true-life experiences of André Devigny as recounted in his memoir), seems practically ready-made for Bresson's recurrent, unique, strong emphases on such urgently serious and considered thinking around entrapment and liberty, and he elicits from it a power that rouses and moves in a way, I think it's safe to say, no other movie about breaking out of prison ever could, no matter how skilled its building of the will-they-or-won't-they make it question, or how thrilling its payoff.

For one thing, all the suspense in A Man Escaped is displaced from the outset, before you've seen a single frame: The French title, Un Condamné à mort s'est échappé ("a man condemned to death made an escape") may be more precise and explicit, but the English title tells you what the outcome will be, too. What Bresson offers instead is a building of suspense in the immediate moments, the tactile experience, of what Fontaine goes through in his imprisonment; it's no coincidence that the first thing we see after the opening credits is Fontaine's hands (in close-up as his fingers flirt with the handle of the car that's escorting him to the prison compound), and only then the rest of him, his body and face. This focus on hands and what they can do is emblematic of Bresson's MO: We see those hands at work many more times throughout Fontaine's prison stint, in long, beautifully attentive sequences (you rarely see such an assured, seemingly inevitable flow of such exactly framed/reframed and edited images as you do here) immerse us in the carrying out of Fontaine's evolving plan: The digging out, with a stolen spoon, of the softer wood holding together the impermeable slats of his cell's door; the impossibly slow creation, first out of the metal wiring of his cot's frame, then out of more suitable material that arrives in a care package, of the rope he will need to climb up and down the prison walls; his use of a safety pin to unlock his handcuffs and his passing of contraband letters and information from his high-up barred window to commiserating fellow prisoners in the courtyard below; his construction, from a lantern frame, of the hook he learns, through the failed escape attempt of another prisoner, he will need to scale an additional obstacle on the way to the outside. These are "small" actions, dull and time-consuming, requiring dedication and concentration, but through Bresson's careful formation and control of image and montage, they become the most momentous rituals, transfixing in their detail, rife with the suspense deriving from the tension between their necessity and tiresomeness, and the ease with which, through one careless move or neglect of precaution, they could call attention to Fontaine's planned escape and seal his doom.

All of that ascetically created but involving, suspenseful tension is multiplied exponentially by Bresson's legendarily resourceful use of sound, which in A Man Escaped, as in his other films, plays a tremendously important role, constituting at least half of the film's world. The precise care and rigor with which Bresson creates the visual experience is doubled by the way he employs the soundtrack: Never has a door slamming shut or a bolt sliding into place sounded as final, never have our nerves been set so on edge by noises (Fontaine's steady scraping, his sweeping up the debris left by his spoon-digging) that must not be heard, as they are here. Fontaine's Morse-code tapping to the prisoner in an adjacent cell; a footstep on gravel; the clanging of a key against a railing -- these sounds become, through Bresson's tightly controlled, supremely focused aesthetic, events with a huge, immediately physical weight to them, doubling and complementing the severe immediacy of what he's allowing us to see.

Above and beyond the interrelationship of sound and image, Bresson does typically (for him) amazing things with offscreen sound, as well. A train we never see may actually be more of a presence through its whistle and chugging (recorded with excruciating care for maximum impact) sounds, awaited by Fontaine and his fellow escapee to cover the tiny but potentially treacherous noises of their escape; a mysterious squeaking heard midway through the escape foretells an unforeseen obstacle presenting itself at the last minute, leaving us just as afraid and consternated as the characters; the gunfire of executions or the sounds of punitive beatings occur within our earshot but not within our sight, which, combined with the austere mise-en-scène and impassive expressions of Bresson's "models" (he only worked with nonprofessionals and detested what he saw as the sins of "acting" against the true, potent properties of cinema), creates a quite literally shocking emotionality. There's also the film's brilliant use of nondiegetic sound in the form of Fontaine's voiceover narration, which, as it becomes clear that he's speaking to us retrospectively, "remembering" what's playing out onscreen, sometimes gives us information purposely left vague by what we can see but more generally serves to undermine or eliminate the what-will-happen suspense to create a void then filled by our enthrallment with what is happening. Or, in another perpetually effective Bresson move, we have the very wary, very sparing use of Mozart's seemingly incongruous "Mass in C Minor" evoking the communal kindred-spiritedness of the prisoners and marking off the points of Fontaine's spiritual and physical progress; this way of using that gorgeous piece of music, bringing it up on the soundtrack at particular, carefully chosen moments, actually comes to underscore, very subtly, the idea that the physical and the spiritual are not opposed, but parallel, interconnected, and increasingly in harmony with one another if the right leap of faith and course of action are taken.

All of these elements are orchestrated by the director so conscientiously, one agonizingly perfectionistic image, sound, movement, and cut at a time, that the release -- both literal, for the characters, and, from our point of view, emotional and intellectual -- in which they finally, inevitably result is almost unbearably tremendous, near-seismic after such a slow build (which is not at all to say that it's a "slow" film; the building, as I hope I've suggested, is riveting and galvanizing and a thing of great, lucid beauty). This is the feat Bresson performed time and again in his work: What we've seen is (more or less) a familiar story, but planed down, de-dramatized to its most seemingly simple, unadorned, plainspoken parts. Yet the effect is astonishingly revelatory, to the extent that a prison break, with no ostentation or overemphasis or anything approaching a frill or flourish takes on the aspect of something as sacred, profound, and mysterious as salvation (whatever meaning you might ascribe to that loaded word). Bresson puts us in the position of, right in the cell with, this prisoner, allowing us to be present for, to actually feel (it almost seems you could touch Fontaine, or the objects and spaces around him) the passing seconds as he performs his tasks and does the labor required by his project, which certainly engages, occupies, and moves us in a certain way, but has the effect of cutting off momentarily the kind of cause-and-effect, psychologically motivated, ultimate-outcome-suspense-driven "action" we're likely more used to seeing in other films, TV shows, Internet content, etc. However, it's a strategy that, as developed with the utmost intelligence and sensitivity and stubbornly adhered to by this one-of-a-kind filmmaker, pays off in waves of emotion that keep rolling over you long after the film is over. In A Man Escaped, for neither the first nor the last time in his miraculous career, Bresson not only reminds us that a pleasure forestalled is a pleasure maximized; he forestalls it to such an extent and in such a finely skilled, inspired, and astute manner that it becomes a whole new, higher, previously unimaginable kind of cinematic pleasure altogether.

Video:

The transfer, which is a 2K digital restoration and presents the film at its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, is glorious: Every precious, careful bit of contrast and shading in DP L.H. Burel's black and white cinematography is present and accounted for, each frame sharp and clear, with barely a trace of wear or tear to be discerned at any point. All of that cleanup has been done conscientiously, too, so that a healthy amount of celluloid grain has been left intact; the true texture of the film hasn't been tampered with or overly digital noise reduced (DNR'd). This edition of A Man Escaped looks, fantastically, like a movie being projected for the very first time.

Sound:Sound is an important element in Bresson's films like it is in few others (an entire supplement included on this release is devoted exclusively to that aspect of the film; see below), and the PCM 1.0 uncompressed monaural soundtrack (in French with optional English subtitles) delivers the film's painstakingly created sound in a manner that adheres to the highest standards of excellence, all dialogue/voice-over clear and crisp, every bolt shutting into place and every tap on a wall or scrape of Fontaine's spoon handle against his cell door (not to mention that beautiful Mozart) almost physically present, just as they were intended to be. Bresson intended for his films to be listened to with at least the same degree of attention (and sometimes even more) with which one watches them, and the sound as presented here unimpeachably respects that intention, facilitating extremely well that vital aural dimension of our interaction with the film.

--"Bresson: Without a Trace," an hour-long 1965 episode of the French TV series Cinéastes de Notre Temps devoted exclusively to Bresson, in which the episode's director, Cahier du Cinéma writer François Weyergans, interviews the reclusive auteur at his apartment (all the better to have on hand the books against which Bresson can check his Pascal or Montaigne or Chateaubriand citations), with clips from Bresson's films interspersed. It's a physically awkward tete-a-tete; the tall and gangly, camera-detesting Bresson is rather charmingly not quite sure what to do with his hands. But his lucidity, ferocious intelligence, and epigrammatic manner of speaking about his work are fascinating and delectable, covering everything from his disdain for 99% of cinema (he makes exceptions for swathes of Cocteau and isolated moments of Goldfinger) to his always-planned, never-executed film adaptation of the Book of Genesis to a description of his inspirations, ideas, and plans for the film he was preparing to shoot, Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), which would become the supreme masterpiece of a uniquely rarefied filmography that scarcely contained anything but.

--The Road to Bresson, an hour-long documentary film from 1984 by Dutch directors Leo de Boer and Jurien Rood centering around the 1983 Cannes Film Festival, where Bresson was present to promote his final film, L'Argent. Using their near-fruitless pursuit of a long-evaded interview with their subject as a framing device, they delve back with admirable thoroughness and analytical astuteness into Bresson's biography and career, recruiting for on-camera interviews a small cross-section of Bresson's more prominent contemporaries and admirers: American writer/director Paul Schrader, Russian master cinéaste Andrei Tarkovsky, and French director Louis Malle. The final interview with Bresson in his hotel room at Cannes is almost scary; he's consented to one question only, and the curmudgeonly yet impassioned diatribe the 81-year-old director delivers in response, sticking fully to his guns in dismissing virtually all of what passes for cinema (he insists, as he had at that point for nearly 50 years, on calling what he does "cinematography" in order to distinguish it from all other films, since he believes virtually everything that we call cinema is merely "filmed theater"), is truly something to see. The film overall is an excellent glimpse into Bresson's severe, intimidating legend that could probably only have been made by a pair like the two recently-graduated, slightly obsessive Dutch film students who undertook to bring it to us.

--The Essence of Forms, a 45-minute documentary from 2010 that includes contemporary interviews with A Man Escaped star François Leterrier; Pierre Lhomme, Bresson's cinematographer on 1971's Four Nights of a Dreamer; his longer-term cinematographic collaborator Emmanuel Machuel; his perennial script-girl Geneviève Cortier; and latter-day French-cinema enfant terrible Bruno Dumont (Humanité, 29 Palms), among others, all of whom either remember, through their fascinating, revealing anecdotes, Bresson's personality, temperament, and working methods (some with notably more fondness or understanding than others) and/or pointing out his place on the timeline of cinema history and his importance to/influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers.

--"Functions of Film Sound," a 20-minute video essay with text from David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson's excellent book Film Art, read by actor Dan Stevens and accompanied by the relevant clips from the film, in which Bordwell and Thompson comprehensively demonstrate and analyze the all-important use of sound in A Man Escaped. This is a must for anyone who wants to either better understand Bresson's artistry in particular, or just more fully appreciate in general the nuances of any director's technical choices and how they affect the experience of a film (in this case, how they work to make a film absolutely extraordinary).

--The film's theatrical trailer, a preview so perfectly fitting that one wonders if it wasn't made by Bresson himself. In addition to a laconic voice-over description of what the film's about, it also features a long, very evocative juxtaposition of sounds -- marching feet and the Mozart piece -- not actually seen/heard in the film itself, but exactly of a piece with it, something more accurately descriptive and representative than the selection of clips from the advertised film more often used in trailers.

--A graphically very pleasing booklet (par for the course from Criterion) featuring an appreciative and analytical essay by Tony Pipolo, a Bresson expert and author of Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film.

A Man Escaped is probably the great Robert Bresson's most accessible work, but it is as uncompromising, elevating, and sublime as any of his other pictures. In telling the story of a French war criminal, imprisoned and sentenced to death by the Germans during WWII, who must painstakingly concoct and execute his escape plan, all the while evading the temptations of despair and making breathtaking leaps of faith (his disciplining and conquering of the suspicion and doubt within himself is, in the way this film plays out, just as vital and suspenseful as his actual jailbreak), Bresson creates an intoxicating, meticulously detailed and perfectly crystallized iteration of his perennial theme of transcendence. The film works so magnificently at every narrative and aesthetic level, and is so pared down to its exact, honed essentials in performance, in camera movement, in sound/music, that it is elevating by the sheer experience of it alone, even apart from its wondrously triumphant ending (something never guaranteed in a Bresson movie, though release of one sort or another -- whether through freedom or through death -- is usually in the offing). Add to the film's masterfulness and unique exhilarations a selection of supplemental materials that are extraordinarily germane, enlightening, and involving even by Criterion's normally very high standards, and you have a Blu-ray release that, aside from making the perfect introductory foreign/art film gift to the budding cinephile(s) in your life (it's easily the equal of more familiar candidates like The Seventh Seal), automatically deserves a place of high honor on any long-term devotee/collector's shelf. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||