| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Materialfilme

Attempts for amateurs like myself to approach and understand avant-garde/experimental films -- like those, collected in Materialfilme, of German husband-and-wife team Wilhelm and Birgit Hein -- require making equivalencies and looking for overlaps. To pose the overlap question: What, in my much more extensive experience with narrative/dramatic movies, might allow me to make a connection with them? There's that moment in Bergman's Persona where the film gets stuck and melts before our very eyes, calling attention to the mechanism of the celluloid in the projector itself and creating a shocking disruption of the "story,"; or the interludes in Paul Thomas Anderson's Punch-Drunk Love for which he used the actual work of an avant-garde/experimental filmmaker, Jeremy Blake, to fill the screen with patterns of fluctuating color momentarily obscuring the adventures and fates of the film's human characters. There's even a bit in Fight Club that counts, when Tyler Durden points to the upper right-hand corner of the screen to call our attention to the reel-change marker. (Perhaps the most famous example would be Kubrick's use of abstract patternings of light and manipulated-beyond-recognition images for the "Jupiter and Beyond" sequence of 2001). When it comes to the equivalencies -- parallel movements in other arts -- there's the mid-20th-century movement in painting toward abstraction, which decisively preferred confronting and provoking the spectator with patterns, shapes, or solid blocks of color, causing an immediate sensation and calling attention to tangible properties of color, paint, and canvas rather than representing anything from immediate, recognizable reality. Or there's avant-garde music, like that of John Cage, that obligates listeners used to certain types of melodies and movements to listen for what wasn't there. Films like those of the Heins (or Stan Brakhage, or James Benning, or Hollis Frampton, diverse and divergent as all of these experimental filmmakers' work is) are like that, but they aren't disruptions within narrative works; they're all disruption. They have no intention of telling us a story, putting themselves at odds with what is by far the dominant, expected use of the medium; they're "difficult" in the sense that they start by refusing us what we've come to expect from most any movie we come across, and then proceed from there. But the perceptual and cerebral doors they open can (it doesn't always; this sort of filmmaking has its failed attempts like any other type) make the effort they demand entirely worthwhile. Such is the case with these two German experimentalists who, signing their films "W+B Hein," engaged with a turbulent political and cultural period for their nation (and the world, when you consider Vietnam, May '68 in France, Nixon, anticolonialist uprisings in Africa, etc., etc.) and fecund period internationally for the cinema by making work that, as the title of this collection suggests, stringently investigates not so much the images usually captured on celluloid, but the "materials" from which the images we're more accustomed to seeing on cinema screens are composed.

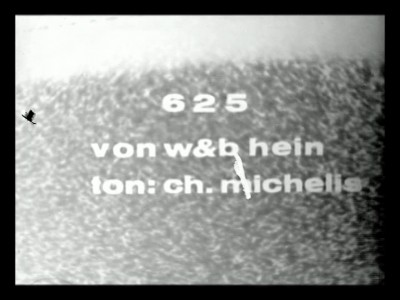

The six films included on this disc were made and originally exhibited (through the underground distribution network of cinema clubs, universities, and programs at arthouse cinemas) between 1968 and 1976. The first, Rohfilm (1968, 20 min.), throws down a gauntlet and announces the Heins's uncompromisingly formalist concerns and approach by consisting of nothing but endlessly, variously repeated snippets of faintly, intermittently recognizable images -- a famous cathedral in Cologne, Wilhelm Hein working in his office, the nude filmmakers embracing in bed, iconic-looking images of a German politician -- mangled, both before projection (with bits of debris, ashes, glue, hairs, and other material a film can gather over a lifetime of wear and travel) and during (through manipulations of speed and focus). The entire, relentlessly mangled strip run through a projector and the halting, stuttering, often literally decomposing frames are the end result, what we actually experience as we view Rohfilm. Our instinct to see what's "in" the pictures is violently thwarted; our attention is forcibly refocused onto their fragile status as images on physical materials, and the patterns and tempos created by those materials and the machinery being used to ("wrongly") project/record/re-project them. Rohfilm is easily the brashest and most aggressive of the works collected here, with a scary but exuberant glee being taken in the hard material fact and the consequent perishability of a material (celluloid) more often used by filmmakers to offer us the illusion of entire worlds; it's like an isolation of, a riff unto itself on that aforementioned Persona moment where the frame sticks and melts. The three films that follow -- Reproductions (1968, 28 min.), 625 (1969, 34 min.), and Portraits (1970, 15 min.) -- build on the scorched earth left by Rohfilm, allowing gradually and carefully for more sophistication, wit, and even beauty as 625 takes a half-hour image of TV "snow" being manipulated through every variation and letting us soak up the abstract patterns of broadcast static and celluloid markings (purposely highlighted scratches, lines -- intentionally cultivated "surface noise" like that used in numerous rock, pop, and rap recordings) thus produced, or Portraits offers a triptych of photos of, respectively, Charles Manson, British train robber Ronald Biggs, and Wilhelm Reich, shuddering and jittering and blurring, sliding from side to side to expose sprocket holes and "Kodak" insignias or morphing from a positive image to a negative image and back again, all as ways of emptying these film images of their representational meaning (provocative enough, in the case of the Manson photo, but not the main point) and recasting/reclaiming them as physical objects.

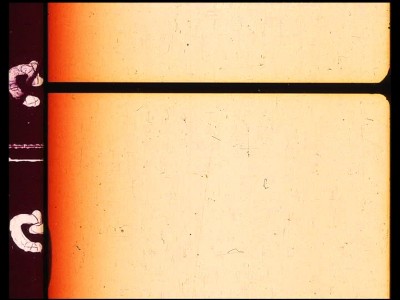

While each of those films has a conceptual and actual force that makes an undeniable impact, arriving at states of being that fascinate and frustrate in equal and complementary measure, it's the two works that the Heins completed in 1976 and that conclude this selection -- Materialfilme I and Materialfilme II -- that pose with the most resonance the questions they're asking of their medium and of us, in addition to serving up the most immediate, tactile visual pleasure of the bunch. These 35 mm films (the others were made on 16 or 8) are composed of the "extraneous," rejected materials that come along with theatrical projection of films: "headers" and "footers" marked with coloring or scrawled letters meant for the projectionist's information, not public viewing. The first, shorter Materialfilme is kaleidoscopic; it seems to be all short bits, making for a rapidly unspooling cavalcade of nervously squiggling, jumping soundtrack strips and numbers and intermittent, near-subliminal flashes of a human figure from, perhaps, a concessions promo or other pre-feature advertisement. The second is beautifully complementary to the first (they really should be viewed in succession), using much longer and now more discernibly organized cast-off bits for a sustained, stately experience that, with its regular movements of two rapid, blurring, evenly spaced strips on the celluloid with stretches of solid color (save for the Heins' all-important surface dimension of pops, marks, and debris) actually does achieve the initially confusing but ever-inviting and rewarding perceptual grandeur of abstract painting, a (seemingly) impersonal but transfixing stimulation that pulls you up short, draws/fixes your gaze, and has the paradoxical effect of leaving one actually refreshed after having been immersed in the film's achievement, which is a degree-zero of pure, self-representing celluloid, movement, and sound. (I would be remiss not to mention here the specially, carefully crafted original "soundtracks" for all of these films by Hein collaborator Christian Michelis, which alternately feature fitting but unexpected mechanical noises and, as in the Materialfilmes, perfectly re-create, in a slightly amplified and eerie form, the familiar pops and squeals and hisses made when running "blank" or otherwise un-soundtracked film through a projector).

It might seem perverse to call something as dirty, difficult, and laborious as much of what is collected in Materialfilme "refreshing," but, as opposed as one might presume the Heins are to a representational cinema that's often enough been dismissed by dedicated avant-garde purists as a philistine misuse of film, work like this can be a bracing, enthralling palate-cleanser, a point of contrast that leaves you awake and alive to all the possibilities that storytelling on film most often leaves unexplored -- an experience that's less of a Damascan-road conversion than a visit to a part of the cinema world you've never been to before, one that can leave you more sensitive and appreciative of just what it is that goes on at the more familiar "home" that narrative cinema represents for most of us. If you're of an even remotely adventurous bent, or in any way able to be swayed from the (arbitrary, after all) rule that a movie first and foremost needs to tell a story, an exposure to at least Materialfilme I and Materialfilme II could be both an eye-opener and a pleasure. It's unfamiliar and radical territory for all but the initiated, but it's hardly as inaccessible and rarefied as all that; a slight opening of the mind and readjustment of assumptions and expectations is all it takes, and before you know it, the films of W+B Hein are showing you things, activating visual-response pleasure centers, and evoking thoughts and feelings you may not have known were available through cinema before, demonstrating, despite their "demanding" nature, a valuable (if unusual) sort of generosity after all.

Note: Materialfilme is a Region 0 disc manufactured in Europe; it may not play on all region 1 players, particularly region-locked models such as those manufactured by Sony.

Video:Each of the six films is presented at the originally intended aspect ratio of 1.33:1, and the films, though they were never meant to look anything remotely like pristine, retain an appearance here that is meticulously faithful to the way they were meant to look, in all their rough, grainy, beat-up, and scarred beauty. With issues of texture and color having been so nicely attended to, the only other potential flaw would be edge enhancement around linear shapes or the rare human figures that appear here and there throughout the films, and there was none that I could detect.

Sound:Christian Michelis's soundscapes are presented as Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo tracks (no dialogue throughout, so no subtitles necessary), and their carefully designed aura of mechanical blankness or failure is as deep and as resonant (those pops have bass!) as could reasonably be expected without compromising the superficially rough/spontaneous/arbitrary but actually frequently quite precise vision of the work.

Extras:--A multilingual booklet featuring an essay on the films by Marc Siegel is nicely designed and very useful as a cheat sheet for those unfamiliar with W+B Hein or their placement among the various movements within underground/experimental film.

--The two Materialfilmes have optional soundtracks by various rock/post-rock artists working, in their medium, in a similar vein to the Heins. This is an interesting move, but the original soundtracks created by Christian Michelis are of greater artistic merit and are more of a piece with the visuals, so the inclusion of additional soundtracks, however conscientiously produced they may be, would seem a little bit redundant.

The six non (or, perhaps better put, anti-) narrative experimental shorts by German avant-gardists Wilhelm and Birgit Hein included in Materialfilme are challenging, cerebral works whose satisfactions it requires some effort to appreciate. But there's really no need to be intimidated: If you've ever contemplated an abstract painting and given it enough thought not to reject it outright via the "my five-year-old could do that!" route, it has something to offer you, potentially something quite uniquely enthralling. Most viewers will experience the cognitive equivalent of growing pains on first exposure (I certainly did), but with an open mind, a little perseverance, and some patience and concentration, the Heins retrain your senses to stop looking for what's not really there and appreciate what (literally, in the most physical and tangible sense) is there, which is the amazingly multitudinous visual and tactile qualities that can be conveyed through celluloid images and projection when they're not being used for the usual purpose of telling us a story or (as with documentaries, usually also with a strong narrative component) giving us information. Yes, it's true that you might actually "learn" something from these works, but they're hardly drily educational. What they are is severe, rigorous; it's that formalist severity that leads to their particular beauty, their particular pleasure. They would probably not be the first non-narrative films I would show someone who may not have seen one prior or be too enamored of the notion, but if you have even a vague idea of or interest in cinema's other, less well-traveled, abstract/cerebral possibilities, or if you're even sort of or maybe inclined to overcome what might be initial confusion or impatience to see something through to its unexpected payoff, W+B Hein have some sensory/intellectual adventures you might like to go on, forays outside the comfort zone that lead to a discovery of forms of cinematic gratification you may not have previously imagined, a horizon expanded beyond what you might have previously assumed was its limit. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||