| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow

Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is technically a documentary by Sophie Fiennes about an especially bold and rich period in the career of German-born painter/sculptor/all-around celebrated artist Anselm Kiefer. But, even more so than Corinna Belz's similarly-minded artist doc Gerhard Richter Painting, the aim of Fiennes's film is much less informational than experiential, with Kiefer's biography, wider body of work, and the huge amount of criticism/appreciation/interpretation that's built up around it over the decades all kept at a radical (but, at least according to Fiennes's sensibility, necessary) distance. Instead, the director uses her camera to show us the artist at work and, most extensively and importantly, the work itself, which her clearly well-developed, highly-attuned filmmaker's instinct has correctly discerned to be uniquely well-suited to a roving, sharp, insatiably curious camera eye like hers, constantly shifting its gaze laterally and around corners, probing in close, and/or pulling back and taking in the wider view, all to ensure that we limn every contour and take in every strange, uncanny, frightening and exhilarating, petrified and petrifying sight (or, perhaps better put in this physically very spacious and landscape/architectural-minded context, site) Kiefer has created.

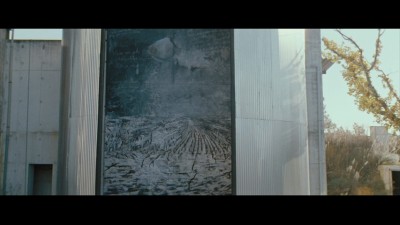

What that is, in general terms as put forth in a very brief, not very descriptive bit of onscreen-text prologue, is Kiefer's creative/destructive reshaping, beginning in the year 2000 and ongoing through most of the subsequent decade, of an estate in the south of France that he took over and began living/working in in 1993. This peculiar location, surrounded by some of France's most beautiful hills, forests, and meadows, was once occupied by a silk factory, now long disused, but its shelled-out physical plant, very incompletely reabsorbed by the slow but inexorable decaying process of nature, still hanging over all the natural beauty like some post-apocalyptic specter. Kiefer evidently found the melancholy, crumbling beauty of this hulking carcass of industrial apparatus tremendously inspiring (the ample views of it proffered by Fiennes make it clear why), since much of the multifarious artistic alterations he's made riff on that theme of inescapable impermanence, the moving and sobering folly of humankind's big, monumental, delusionally massive and fixed projects seen in hollowed-out, archeological retrospect: He's erected misshapen, weathered stone towers, simultaneously ancient and futuristic-looking; constructed a vast underground labyrinth/forest full of twists and bends and a sense of entrapped, eternal disorientation; and built anew or repurposed already-exiting houses, worn-out dwellings abandoned as if after a war or disaster, occupied only by his time-weathered sculptures and other pieces; and generally left "relics" everywhere -- carefully designed and aged and broken shards and bits of some vaguely familiar but unidentifiable civilization -- overall cultivating an ineffable, eerie, mysterious sense of some half-excavated ruin bearing evocative, disconcerting traces of lives, now long gone, once marked by joy, creative and practical accomplishment, and horror.

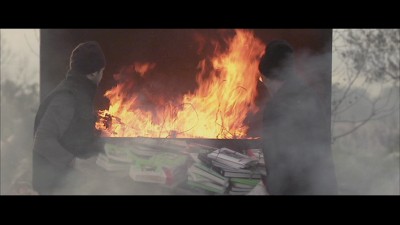

Interspersed with Fiennes's languorous views of all this civilization half-succumbed to the inviolable laws of entropy is footage of Kiefer and his assistants at their paradoxical work of creating just the right degree of destruction to make this world what it is, much of which involves rivetingly manual, heavy, involved labor with the use of blowtorches, molten lead, shards of methodically smashed panes of glass and bits of systematically broken plates, cracked and unwieldy, monolithic slabs of stone. The illusory remnants and remains of things that ornament Kiefer's sites -- charred or petrified books, worn-away scribblings on walls, perhaps most disconcertingly stiffened robes and piles of teeth (redolent of the Holocaust, apparently an important theme in Kiefer's work, though not explicitly spelled out as such, either there or in the film) -- have to be carefully subjected to the artist's palette of destructive effects, which is fascinating to watch. It's physical, grimy, earthy work, the invigoration it provides the artist and his helpers a feeling that extends to us as we watch them go about their efforts.

But Fiennes (and, one surmises, Kiefer himself) is less interested in all that noise and activity and heavy labor than she is in the finished work that so brilliantly bears its haunting echoes. We don't see a single human figure until 20 minutes into the film (even after that, Kiefer and his crew are relatively estranged figures, not really "characters" with personalities or psychologies we're meant to find interesting or become familiar with). Fiennes brings us fully into Kiefer's depopulated world from the start, with a long sequence of gorgeously shot views of his anti-monuments and ravaged excavations and caves, her camera moving very measuredly but near-constantly over the views on hand and, most impressively and beguilingly, floating forward and backward through the spaces like some all-seeing, disembodied Steadicam eye, traveling toward or revealing who knows what in the final view or around the next corner. These sequences, which together comprise at least half of the film, are usually accompanied by the secular-celestial music of mid-20th-century composer Gyorgy Lygeti, lending our slow-traveling views of these burdened, haunted, destroyed/abandoned spaces an even more Kubrickian effect than they have on their own (Kubrick himself having used Ligeti extensively to complement his own uncanny visions in 2001 and The Shining).

The way Fiennes has structured the film, alternating these wordless stretches of exploration and visual exposition with depersonalized and equally graceful (if not so kinetic) footage of Kiefer in the throes of destructive/creative fabrication, prioritizes the work above all else; it's a formalist approach that denies us something we're used to (biographical information, "candid" moments, personality, narrative-like organization) to give us what filmmaker and artist consider the crux of the matter. In a way, Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is itself, like some of Kiefer's elaborate landscaping/architectural projects, a labyrinth, at the center of which lies an interview/interlude with the man who orchestrated and built all we've seen around it, but with the full understanding and insistence that the philosophical and aesthetic musings therein -- talking-head type stuff, still exquisitely framed, but more in keeping with a more conventional idea of documentary -- are a center, not a bottom gotten down to or any sort of explanatory conclusion or fully-orientating compass. Both Kiefer and Fiennes are uninterested in such linearity; they're all about the perpetual and cyclical, the continuum -- the overlapping and blurring of ending and beginning, nature/landscape and art/civilization, documentary/experimental film, death/decay and rebirth. It's a purposely mysterious, inconclusive, disorienting film because the artist and work it's documenting mean to unsettle, not satisfy or give us clear meanings or closure. But the richness and beauty of such a serendipitous meeting of Fiennes's cinematic sensibility with the aesthetic philosophy and approach of her subject offers deeper and more substantive rewards than any more pat, direct rundown of Kiefer and his work might have done. It opens a door as widely as possible on one artist's sublime (in the vast, humbling, terrifying Kantian sense) vision of human civilization and its ever-unstable place in the natural world, and it leaves that door open, neither actively beckoning nor rebuffing; it's up to us to decide whether we'll accept the provocative invitation/challenge and put forth the effort -- well-rewarded, I assure you -- of stepping through it.

Video:

The transfer, which presents the film anamorphically at its originals widescreen aspect ratio of 2.35:1, does quite a good job color-wise, with the film's cool but vivid Fujifilm tones coming across very well. Iffier is the texture and stability of the image; there's nothing horribly distracting, but there is noticeable edge enhancement/haloing throughout, and depending on whether a 35 mm print or a digital version was used for the transfer (it appears to have been the former), there's a faintness of the film texture and a certain slickness/softness to the image in many sections that might suggest overuse of digital noise reduction (DNR).

Sound:Both Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo and Dolby Digital 5.1 surround options (in French and German, with non-optional English subtitles) are available, and while both tracks are great -- all sounds clear and vibrant, fully dimensional and solidly present, with no distortion or imbalance at any point -- I'd use the 5.1 option if available in your setup; that Lygeti score coming at you from all angles, all its richly layered highs and lows sounding so sonorous, really helps set the film's tone as intended, and the sounds that Kiefer and his crew create while at their work -- shattering glass, rumbling blowtorches, etc. -- fill your viewing space up almost jarringly, for a true you-are-there feel.

Extras:Nothing other than the film's U.S. theatrical trailer.

An overwhelming, sometimes bewildering (in the good way) immersion in art conceived and created on a grand scale, Sophie Fiennes's Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is an intimate, barely-guided tour through a particular time and place in German-born artist Anselm Kiefer's long career -- the first decade or so of the current century, when he transformed an abandoned French silk factory into a massive workshop and permanent showcase for his vast, conceptually dizzying landscape and architectural sculptures. Fiennes's show-don't-tell approach is exactly in keeping with the haunted, taciturn sensibility exuded by what Kiefer has accomplished; the ability of her stately-gliding camera to not merely "capture" but to put us into Kiefer's carefully, laboriously constructed labyrinths and ruins (as well as the more familiar types of paintings and sculptures with which he's populated the huge estate) more than compensates for the questions (who is Anselm Kiefer? What purpose and meaning does this scarily ambitious, physically gargantuan project have?) we're left to answer on our own. In fact, that combination of the vivid, immediate physical presence of the artworks and the film's refusal to orient and explicate for us is unsettling in a way the precisely matches Kiefer's work itself. Whether one finds the experience frustrating or awe-inducing (most viewers are likely to respond with a bracing, healthy mixture of frustration and awe), the film has to be considered a success on its own terms as it conscientiously and compellingly discovers just the right use of the cinematic language to best translate, complement, and do justice to its challenging, fascinating subject. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||