| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

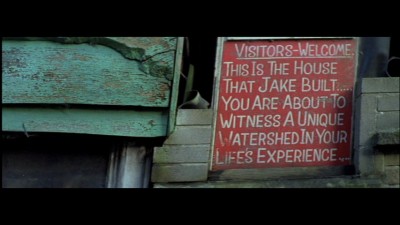

Two Years at Sea

The description on the back cover of this vital DVD containing British artist Ben Rivers's mind-blowing, near-spiritual experience of a feature film, Two Years at Sea, makes it sound as if there's a story being told: It names the film's subject, a man called Jake Williams, and informs us of the origin of its title, that Williams spent two years working at sea (on a fishing boat, presumably) to finance the isolated, cabin-in-the-woods wilderness existence he's always dreamed of. But, interesting as it is, none of that information is mentioned at all in the film, nor is it in any way necessary to understanding it. Rivers's aims are not by any stretch documentarian in that way; he has little interest in introducing this man to us as a biographical "character" or explaining to us how he came to swell and survive with such unusual independence in such a wide-open, unspoiled, mysterious landscape. His mission is higher, more poetic; he means not to merely describe the eccentric Williams and the strange, almost perversely simple way of living he's striven for and evidently attained, but to find and use the right cinematic vocabulary and syntax to convey some of the essence of the very modest, sublimely peaceful character this self-exemption from the "civilized" world can grant to a life, the different, perhaps more natural (or at least more humane) tempos and textures for which it allows.

What that means for the privileged viewer is that not only is this bearded, reclusive, vaguely hippie-like man never actually named in the film, but we never even hear him speak; Rivers, his camera, and his sound recording device have embedded themselves in his life for a stretch so that we may observe, quasi-reverentially, his mundane rituals (the morning routine of toilet and shower; the elaborate and laborious but savored making of food and drink), his work (wood-chopping to music played on what appears to be a child's ancient, discarded portable record player; the hoisting, with his antiquated all-terrain vehicle, of his trailer-home to higher ground in preparation for winter), and his well-deserved, enviably plentiful leisure (reading, writing, still and meditative repose; the fashioning and hauling of a sort of raft of his own design in which, in an achingly languorous, extended scene, he lets himself simply float in a vast, hidden lake nearby). The details are bountiful, fascinatingly rendered: From the widest, most terrible (in the old-fashioned, Schopenhauerian sense) views of the mysterious natural world surrounding Williams -- the forests, the meadows, the thick, gently all-enfolding early-morning fog, the swirling clouds and rain or the piercing clearness from the huge sky above -- are set in an unlikely but complementary rhythm with the tiniest cut-in close-ups -- that record player; the plants in the windows, alternately fogged or reflective and rain-spattered; the mist created by the hot shower water against the cold surfaces of his domicile; his washing on the line; dozens of mysterious found objects he's deigned/made useful to him -- Rivers shapes an endlessly patient, incredibly intuitive, hyper-observant picture that fully accommodates the elusive contours, the becalmed heartbeat and the infinite, serene variety and aliveness to the world that this dreamed-of life made real provides for.

It's not, of course, only in what Rivers's brave, flawless intuition leads him to show us, but the how, and his aptitude for locating and enacting the right style and technique is stunning, perfect in its imaginativeness and conscientious application. He uses grainy, old-fashioned, possibly intentionally weathered or otherwise re-shaped 16 mm black-and-white stock, incongruously but rapturously blown up into 'Scope-ratio widescreen for a visual texture, a particular thickly sensuous, flickering physicality you can practically touch, that, far from being ornate or imposed, or distancing us from the solidity of the world onscreen, immeasurably enhances our sense of its reality, its immediacy for us; the "rough" by design, sometimes spotted, lined, or weatherbeaten-looking image, accompanied by a pristine soundtrack, dialogue-free and almost entirely devoid of non-diegetic sound but replete with Williams's whistling as he works, his scratchy and primitively-played records and tapes revealing an anti-contemporary, obstinately roots-seeking, R. Crumb-like esotericism to his musical tastes, and all the hundreds of sounds of nature animal, vegetable, and mineral, makes for a vivid, unshakeable intimacy, as if we're seeing not a picture of a place made by familiar technological means but a timeless, private projection of a subjectivity somehow rendered as demonstrably true and real as anything, of how this world feels, what it means, the totality of its look and feel and sound, to the one who has miraculously willed himself into it. It's what we might see in home movies brought back by some dream-anthropologist from a voyage into the subconscious, Walden-conjuring mind of H.D. Thoreau himself.

The perspective Rivers thereby imbues through his wonderful film is so strong that any trace of what might normally be the main focuses in a more conventional documentary -- the stray, neglected newspapers that might concretize time and place; the many photographs, all unidentified, of what must be people and places, perhaps images of a younger, other self, from Williams's life before -- is startling, like a relic from some alien unreality, necessary to remember but also necessarily dim, distant, amorphous. This world, not idealized or romanticized but genuinely explored for every indelible impression, every inexpressible feeling it gives, is made to immerse us so fully, pulling us with its solid, relentless, alluring gravity, that we easily understand, without any verbalized justifications or psychologizing backstory, what would make this man forsake ours for it. There's nothing of what's commonly used for suspense or attention-holding on hand here, but you don't quite want the experience to end; it's not that you need to know what happens next, but that you don't want to leave. In the last shot, when Williams's lantern finally, oh so slowly lets his peaceful face fade into the darkness over which the end credits appear, it's jarring to return to the "real" world that, in the glorious light of this film, somehow feels contrivedly cluttered, falsely "busy," not so verifiably real. It's the perfect note to end on, though, cementing our extraordinarily close, complete relationship to this man's and his interlocutor's visions: Upon our return, we feel as displaced, as regretful as he would if he had to come back to our world and leave behind his humble, authentic, profoundly beautiful, and entirely possible paradise-now.

Video:

As one has come to expect from Cinema Guild, the transfer of the film is punctilious and splendid: The very particular, very textured and physical character of Rivers's 16 mm black-and-white is vital to the experience, and it's all been preserved wonderfully in this transfer (presenting the film anamorphically at its original widescreen aspect ratio of 2.35:1), all of its glows and fades and varied contrasts and, yes, its natural and essential grain (it's unimaginable that anyone would DNR or otherwise smooth the character out of Rivers's images, and thank goodness not a step has been made in that direction here) fully present and accounted for. Darks (of which there are many) are as solid as intended, and virtually no compression artifacts such as aliasing or edge enhancement/haloing can be seen throughout. A very nice job, picture quality-wise.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 soundtrack is perfectly sufficient to the meticulous sound design with which Rivers has imbued his work: The film is entirely dialogue-free, and virtually devoid of any non-diegetic sound, but what we hear -- the sound of rain falling or of snow melting and trickling, the striking of an axe as it splits apart logs, the intimate percolations of a coffee pot -- is essential, and each sound, which Rivers attentively treats as uniquely precious and meaningful, is rich, full, clear, and solidly present, all qualities that come to us fully intact in the soundtrack as it's been carefully treated and conveyed to us here, with no distortion, imbalance, or any discernible flaws whatsoever.

Two short films by Ben Rivers: This is My Land (2006, 14 min.), which also takes Williams as its subject and is very much a precursor to/trial run for Two Years at Sea; it's exquisite in many of the same ways, but Rivers discovered along the way that dropping Williams's descriptive, Scots-accented speech and widening out the frame (this film appears in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio) for the feature would lend it even more real, rough-hewn grandiloquence (included in the menu is a helpful prologue in which Rivers describes the overlap between his methods, approach, and philosophy and those of Williams, which has led to the wondrous and magnificent conjunctions of form and content we see in these films). I Know Where I'm Going (2009, 29 min.) borrows its title from a wonderful old Powell/Pressburger film but has quite a different meaning; it's another landscape journey, but different from the other two included here. With narration about projected human traces in a post-human Earth many millennia from now by geologist Jan Zalasiewicz and a Kubrickian-vertiginous, almost too-spacious sense of sound and vision, along with Rivers's deployment of color from his rich-as-always16 mm palette, this time his capability for cinematic creation makes for an anomalously reassuring, premonitory slice of post-apocalypse that may be the most haunting of all the indispensable achievements compiled on this disc.

--About 30 minutes of deleted scenes that were presumably omitted to avoid repetition (each of the textures and moments seen herein has a one-time-only analogue in the film proper), but left as we are with a hunger for more of Rivers's extraordinary vision, this makes for a most generous and welcome addendum to the main course.

--A graphically very pleasing, four-page/fold-in insert booklet whose beauty is matched by its content, a brief tribute/essay on the film by critic Dennis Lim.

--A selection of trailers for other Cinema Guild releases, all of which, from The Day He Arrives to Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, are unhesitantly recommended as well.

Every filmmaker worth his or her salt has a vision, but that of Two Years at Sea director Ben Rivers gives us "vision" more literally than most: Ostensibly a documentary about real-life subject Jake Williams, an Englishman who's chosen a bare-bones, DIY, extremely rural life as a sort of recluse from so-called civilization, the film, shot in gorgeously tactile 16 mm black-and-white, seems to let us into an existence at once absolutely real and almost completely outside of time. Its wordlessness and mystery create an enrapturing sense of living, momentarily experiencing for ourselves this man's quixotic dream -- his personal, Walden-like vision -- of leading a calm, quiet, uncomplicated, "natural" life. Like the also technically "documentary" landscape films of James Benning, Rivers is not representing reality so much as he is capturing sublime essences, refocusing our attention on an elusive but transformative Truth -- life, nature, and time in the way only serious and sensitive art can do. Two Years at Sea may depict a real man's real, inspired, inspiring life, but that's only for starters, not even the half of it: Its aim is not to inform but to transport us, and that it does, most elegantly and hypnotically, delivering us, at least for its too-brief, over-in-a-flash 90 minutes, into a rare, contemplative state of grace. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||