| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

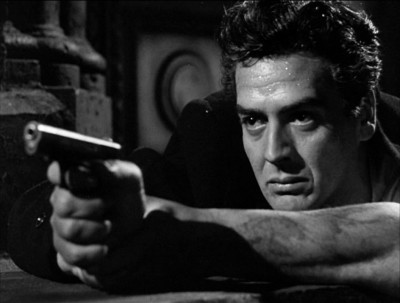

Cry of the City (Fox Cinema Archives)

Nasty, sick-humored film noir classic, on DVD for the first time. 20th Century-Fox's often maligned (by me) Cinema Archives line of hard-to-find cult and library titles has scored a major coup: the first DVD release of director Robert Siodmak's Cry of the City, the 1948 meller from Fox, produced by Sol C. Siegel, scripted by Richard Murphy, and starring Victor Mature, Richard Conte, Fred Clark, Shelley Winters, Betty Garde, Berry Kroeger, Tommy Cook, Hope Emerson, Roland Winters, Walter Baldwin, and Debra Paget. Beautifully designed in striking black and white, with a soul as grimy and beat as its squalid surroundings, Cry of the City may not sport the most original storyline--two guys from "the neighborhood," one good, one evil--but it packs a punch in its visual schematic, in its sick, cynical jokes on how we perceive criminals and cops, in its assorted supporting "grotesques," and in its doom-laden (and yet in the end, hopeful...) lead performances. Required viewing for anyone interested in the noir genre. A trailer is included here in this good-looking transfer.

In a cavernous, empty ward at City Hospital, last rites are being performed for cop killer Martin Rome (Richard Conte). Grievously wounded in his fatal shoot-out with the officer, Rome clings to life as his gathered family weeps and prays at the foot of his bed. Nearby, cynical, seen-it-all NYPD detectives Lieutenant Vittorio Candella (Victor Mature) and Lieutenant Jim Collins (Fred Clark) offer an impassive counterpoint: they've got questions for Rome about another notorious case--the de Grazia torture/strangulation jewels heist. Even if Rome survives his wounds...he's doomed in the electric chair. On the sly, Rome's sweet, innocent girlfriend, Teena Riconti (Debra Paget), visits him, distraught over his condition; when the cops learn of this visit, they put 2 and 2 together (a de Grazia ring was found on Rome) and get 5, thinking she may be Rome's female accomplice in the de Grazia slaying. Rome's post-op visitor, slimy lawyer Niles (Berry Kroeger), has a proposition: confess to the de Grazia heist and he'll slip him 10 Gs for his troubles, which would set up his family and Teena quite nicely. Rome, on principle, refuses, which makes Niles show his true colors: do the deal or innocent Teena gets ratted out for a crime she and Rome didn't commit. Eventually escaping from the prison hospital, still-recovering Rome races against the clock to track down the de Grazia jewels to finance his escape, with Candella in hot pursuit.

This release of a long-absent, much anticipated title does help a bit after all those Cinema Archives pan-and-scanned widescreen titles, I suppose...particularly if I'm correct in that this transfer of Cry of the City contains two scenes with Shelley Winters that are often missing from old prints of the movie. Long sought-out by noir fans due to its infrequent showings on television over the years, Cry of the City may not be perfect noir, but it does find one of the genre's most identifiable directors, Robert Siodmak, near the top of his game, rendering a movie that resonates on a darkly funny, perverse level far beyond what its relatively routine source material should bear. Based on the Henry Helseth bestseller, The Chair for Martin Rome (for which Fox paid close to a quarter of a million dollars in today's money), Cry of the City's original script was worked on by Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer, which was then turned over to John Monks, Jr., and then finally worked on by Richard Murphy (Boomerang!, Panic in the Streets, The Desert Rats, Broken Lance, Compulsion), who received sole on-screen credit. According to what I've read, the movie was set to be filmed in San Francisco, with Lon McCallister in the role of Rome. Then, Fox mogul Darryl F. Zanuck favorite Victor Mature and Richard Conte were cast, but in the opposite roles they eventually played on-screen, until Zanuck had second thoughts about putting Mature in another criminal role, after the actor scored big-time as a sympathetic crook in the previous year's hit, Kiss of Death. A last-minute title change from The Law and Martin Rome (which certainly spelled out the dichotomy that Siodmak was going for) was decided on by both exhibitor resistance to the title, and threatened litigation from a real-life lawyer named Morton Rome--a lucky happenstance, since you'd be hard-pressed to find a more appropriate title to evoke the existential, violent angst of the noir genre than Cry of the City.

Watching Cry of the City after not having seen it since "film school" days (yeech), and immediately feeling an over-abundance of ideas and thematic connections and symbols woven into each information-packed frame...I was again reminded of how careful one has to be not to "over-read" the intentions of the director in his mise-en-scene or his structuring--an easy thing to do with noir, since it's so palpably dynamic and accessible in its deliberately over-emphatic visual presentation (a lot of those old directors would laugh at some of the stuff that we come up with after watching their movies). Throwing critical caution to the wind, though, and taking that thought to its logical progression: if you can't be careful...be good. At least acknowledging you may be playing an intellectual parlor game, seeing things and making tenuous and possibly specious connections in what very well may be "happy accidents" for a director--observations that could have more to do with your own sense of aesthetics (as well as a competitive, vulgar desire to hit a critical bull's eye no one else saw), rather than any conscious, legitimate attempt by the director to "say" something--that kind of admission actually frees you up to have some fun in your analysis.

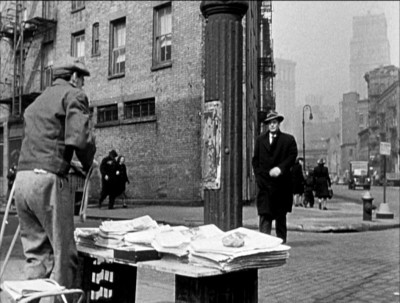

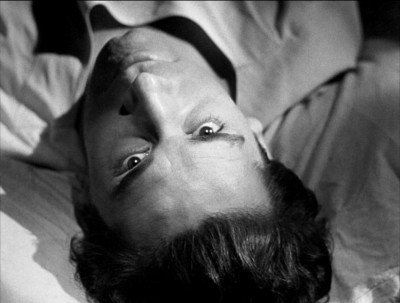

And Cry of the City is fun to watch, not only in that purely pleasurable way a mere "entertainment" delivers if it's been carefully crafted, but also in the way it can resonate above and beyond those mid-bar expectations if some compelling ideas have been artfully incorporated into the mix--if the methods of expression are the movie's messages. The opening shot of Conte, lying in a hospital bed, is a perfect example. Shot in stark, irregular planes of black and white, Siodmak and his cinematographer, Lloyd Ahern, have Conte in a white gown, with the body of a priest throwing a black shadow over half of him, the held Bible glowing white against the black void of the hospital ward, with the symbolism of the iron bed bars equally obvious (Siodmak will bookend this fatalistic image at the movie's deeply pessimistic finale--at least for Conte--with SPOILER ALERT Conte prone again on the wet, dirty pavement, eyes open, stone dead). It's a remarkably composed shot, dense with information conveyed to us without a word, but when we see where Siodmak is going with this opening--making us culpable, tricking us in his perverted, sick joke game of framing this repellant cop killer as some kind of victim we should somehow pull for...and actually succeeding until the rug is pulled out from under us--that's when we see a director who's working on a whole different plane than fellow craftsmen, no matter how competent, who just want to deliver an exciting story.

Siodmak's deft tricks of noir semiotics can be found in almost every scene. When Kroeger turns Conte's confident world upside down by threatening the one pure, valuable element in Conte's life--Paget--Siodmak shoots him upside down, eyes wide and staring into the camera, before he tries to strangle Kroeger. Freudians would have a field day discussing the barely submerged misogyny of a remorseless, manipulative womanizer like Conte, so Siodmak often shoots the women in Conte's life initially bathed in dark, menacing shadow, emerging out towards Conte (Paget out in the hospital hall, the celebrated shot of Hope Emerson's threatening silhouette advancing on Conte, and the rarely mentioned shot of Conte's faceless, shadowed mother, throwing open their apartment's sliding doors, looking almost exactly like Hitchcock's later shot of Norman Bates dressed as "Mother," as Conte initially cowers in fear). As almost a coda to Conte's fear/hatred/manipulation of women, when SPOILER ALERT Conte is delivered his ultimate fate by negative/positive image Mature (Mature, wounded and "on the run" like Conte, wears a black coat and white smock to Conte's white coat and black shirt), Siodmak has Conte attempt to reassert his manhood, one last time, sitting up and flashing a switchblade knife in a grotesque parody of phallic assertion, before he slumps back dead.

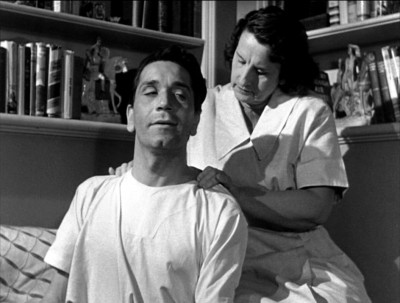

This nightmare world of chiaroscuro symbolism is further made unsettling by the sickly cynical tone that permeates and curdles the script--a tone that is also frequently blackly humorous. The downbeat oppression of the fated corruption of the soul is unrelenting in Cry of the City...until Siodmak and company offer a glimmer of hope at the end. As Conte's family weeps for his recovery, cops Mature and Clark roll their eyes at each other, with Clark making a loud, bad joke about Conte having no hospital "record." Conte, very likely to die on his way to the operating table, still has the balls to tell lawyer Kroeger to "go fry," in response to Kroeger begging for a confession--a tough guy response that gets an appreciative sneer from Mature and a completely uninvolved, "That's tough," from Clark. When Mature makes his way up the stairs to Conte's family's apartment, a little boy waits until he reaches the door before slamming it in his face (about the only place you'll laugh out loud in Cry of the City). The true depth of Kroeger's moral rot is revealed in a throwaway line when he assures Conte he has a way of getting him off the hook for killing the police officer: the cop has killed before, with the implication being Kroeger will "try" the dead officer in court, rather than defend Conte. Sickest of all in Cry of the City is the introduction of one of noir's most memorable "grotesques," masseuse/torturer/strangler Hope Emerson, who repulsively stuffs her face at breakfast while robotically droning on about buying a place in the country to ensure getting wholesome food (her massage of Conte's back...before she almost strangles him, is a foul image you're not likely to soon forget).

Of course, the biggest sick joke in Cry of the City is on us, as director Siodmak makes us care about Conte's plight when logically we should have every intention of despising him. Due in part to Conte's flippant, charismatic turn here (which Siodmak no doubt intended), as well as to Siodmak's careful placement of this reprehensible creep within a persuasive "anti-hero-making" framework, Conte's cheapjack thug who uses everyone without the slightest bit of compunction, actually starts to worry us when he displays the intense love he states he feels for Paget (heightened later when Siodmak executes a neat, morally-compromised Hitchcockian hospital escape, where we're on the edge of our seats, hoping this merciless killer makes good his escape). That opening sequence in the hospital, where Conte is bathed in white light as the Madonna-esque Paget beatifically rains tears down on him, sets up Conte as the victim here, not the cop he killed. Cleverly (and aberrantly), scripter Richard Murphy has the dead cop's case made for him by buffoonish Clark, who ineffectually rants about the cop's widow as Conte feigns a faint (if Siodmak had showed that widow, we never would have foolishly "pulled" for Conte). Murphy and Siodmak never try to hide the moral compass of the movie; Jule the crippled newspaper boy hits it right on the head: Conte's devoted mother would have been better off if Conte had just croaked in the hospital. Mature is disgusted with Conte because they came from the same place, the same squalid neighborhood, but Mature is trying to save a kid like Cook, while Conte, Cook's own brother, is asking the hero-worshipping kid to aid and abet.

Of course, this is where Siodmak and company turn the tables on us: Cook. Even though the movie drops the ball by cutting away right when we need to hear what, exactly, Mature says to Cook to finally get the kid to turn against his brother (a big sticking point when your start thinking about the movie after it's over), the finale is a powerful indictment not in favor of that old saw, "Crime doesn't pay," but an indictment against us, the viewer, who actually cared about this manipulative, heartless criminal Conte. SPOILER ALERT Lying dead on the pavement, Cook doesn't cry over his brother but rather goes to Mature, who asks the boy for help getting into a police car, before tenderly embracing him as the boy weeps. This is how a brother should act towards another brother; this is the example an older brother should set for a hero-worshiping kid--not the easy moral corruption that Conte offered to Cook. We rooted for Conte to somehow "get away" and reform, but we knew, from all the signs Siodmak gave us, that he would never do that, as Mature knew all along, too. We were the dopes for following Conte, rooting for a criminal as we do so often in American cinema, while dismissing Mature as a well-meaning but ineffectual executor of the law. What exactly were we thinking, Siodmak seems to be saying with that last shot, as SPOILER ALERT Conte's dead eyes stare off into the void, as Cook's "new brother" offers comfort? It's the last, best sick joke in Cry of the City, and it's on us.

The DVD:

The Video:

According to some sources I've read, the two scenes with Shelley Winters (the publicity photos and inside the bar) are missing in a print that was widely circulated in the U.S. (the American Film Institute catalog documents this, as well). Well, I don't know when those were restored, but they're here now(isn't that a British censorship title card at the beginning of this trailer?). Otherwise, the fullscreen, 1.37:1 black and white transfer for Cry of the City looks quite good, with blacks that hold, good contrast, some grain, and minor screen imperfections, as expected.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono audio track is okay, with low hiss, and no subtitles or closed-captions available.

The Extras:

An original trailer is included as a welcome bonus.

Final Thoughts:

Essential noir. Director Robert Siodmak, one of the genre's leading helmers, fashions a cynical, nightmarish joke that has us rooting for a cop killer...before he makes us see how screwed-up we are in our love of American movie criminals. Richard Conte has never been smoother and more disturbing, and Victor Mature again delivers. I'm highly, highly recommending Cry of the City.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||