| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

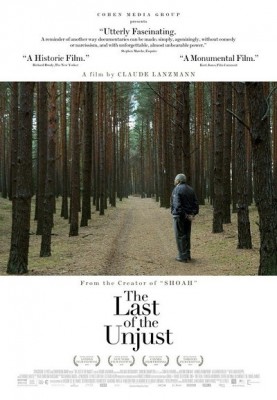

Last of the Unjust, The

Lanzmann's obsession with the minutiae likewise serves to explain and understand the essential logistics of the Final Solution; how, for instance, trains transporting Jews to the death camps operated within Europe's complex rail systems. In so doing Lanzmann makes plain that the death camps were with horrifying vividness operated much like any other transport business.

Now 88 years old, Lanzmann revisits the subject in a new film, The Last of the Unjust (Le Dernier des injustes , 2013), a nearly four-hour documentary about Austrian Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein (1905-89), the only Jewish Elder of Theresienstadt to survive the war, perhaps the only survivor among all of the Elders in all of the various concentration camps.

As part of the administrative body formed by the Nazis to manage the various Jewish ghettos and to act as liaison officials, Murmelstein worked closely with Adolf Eichmann, one of the major architects of the Holocaust. Later, within Theresienstadt, Murmelstein was despised by his fellow prisoners for his hardline policies. For these reasons he was accused of collaborating with the enemy, some Jews even calling for his execution. After the war he never set foot in Israel, instead spending the remainder of his life in exile, in Rome.

Like Shoah, The Last of the Unjust consists almost entirely of testimony, culled from a week's worth of interview footage Lanzmann shot in Rome in 1975, exquisitely cut with new footage of the various locations Lanzmann and Murmelstein discuss (including Madagascar), sometimes with the director, much more visible than in Shoah (that's him on the poster, not Murmelstein), reading long passages of text at these places, as if filling in important gaps. The film presupposes a familiarity with Holocaust history, personalities like Eichmann, and some of the controversial events at Theresienstadt (an iPad and Wikipedia are handy viewing supplements). It's also a challenging film that asks its audience to carefully weigh Murmelstein's testimony, full of digressions and references to events and people with which the movie audience isn't necessarily familiar, and for them to draw their own conclusions.

For his part, Lanzmann clearly agrees with the verdict of the Czech war crimes trial that exonerated Murmelstein. Nonetheless, the extremely articulate Murmelstein's emotional distance from the horrors of Theresienstadt surprises Lanzmann and his audience: Murmelstein talks for long, uninterrupted takes with a sense of urgency but, unlike some of Shoah's participants, is never emotionally overwhelmed by his amazing recall and certainly never breaks down in tears. He likens his impossible position in the Holocaust story to that of a surgeon: if you were to cry over the body of the person you're operating on, that person isn't going to survive. In another sequence he suggests his role was rather like that of Sancho Panza, the realist squire trying to affect a positive influence on his mad companion.

Tens of thousands of Jews died at Theresienstadt, from starvation and disease; many others were executed for the most trivial of perceived infractions. Even so conditions there were somewhat better than at the other camps, most notoriously Auschwitz. Murmelstein makes the case, logically, that he and the other Elders had no clear knowledge of the extermination going on elsewhere. They had a vague understanding that conditions were much worse at the concentration camps to the east, but assumed they were grim ghetto communities similar to theirs.

Murmelstein is essentially a pragmatist. He candidly states, believably so, that when the Nazis would prepare to deport Jews he had no choice but to comply with their demands. Though unaware the purpose was explicitly to exterminate them, Murmelstein nonetheless drew the line, he says, at selecting those to be shipped out. He argues, again convincingly, that his refusal was a conscious tactic, to deny the Nazis any moral absolution from placing such compliancy in the hands of the Jews. As Murmelstein was by this time the only comparatively compliant Elder left, the Nazis didn't press the matter further.

Lanzmann asks Murmelstein about Theresienstadt, the controversial propaganda film made by the Nazis during an official visit by the Danish and International Red Cross. The film, of course, was a total fabrication, presenting Theresienstadt as a "model ghetto," a "gift by Hitler to the Jews" where its prisoners ate well and lived in relative comfort. Murmelstein is again pragmatic, arguing that if the lie meant that his people would receive blankets, glass for their windows, new beds for the elderly, who was he to refuse? In one of The Last of the Unjust's most disquieting moments, Murmelstein notes that even the Nazis' deportation of the camp's sickest inmates, to their certain death it turned out, probably spared the larger community from the further spread of communicable diseases. Paraphrasing Isaac Bashevis Singer, Murmelstein notes, "In Theresienstadt there were no saints. There were martyrs, but martyrs are not necessarily saints."

Through Murmelstein's testimony, details about Eichmann and the Final Solution become clear, particularly how complete disorganization in treating the "Jewish Problem," mainly plans to deport Jews en masse from Europe, fell apart, and that how when the ghettoization of the Jews, passive extermination, failed - partly due to Murmelstein's leadership and resilience - for the Nazis the gas chambers and ovens seemed the only viable answer.

As with Shoah, Lanzmann's use of extremely long takes contrast the often attractive landscapes and centuries-old city streets with the unimaginable human suffering occurring on those same spots 70 years ago. An early scene shows Lanzmann standing at a platform where several long freight trains seem to interrupt his on-camera narration. Instead the director leaves all this outwardly interminable footage in. Gradually though, the viewer is able to look beyond this present-day inconvenience to be reminded how these same train tracks were perverted for a different kind of freight, for human behavior at its most reprehensible.

Video & Audio

Lanzmann seamlessly integrates his 40-year-old 16mm footage of Murmelstein, footage that looks great in spite of that format's limitations, with new scenes apparently filmed in 35mm widescreen. The 5.1 DTS-HD audio similarly subtly adds dimension to the newly shot footage, with ambient noise filtering through the surround channels. A Dolby Digital 5.1 mix is also included. Mostly in French and German with very good English subtitles.

Extra Features

The slight extras are a nearly worthless booklet with pictures but almost no next; a trailer and too-brief interview with Lanzmann, both in high-def.

Parting Thoughts

A worthy companion piece to Shoah, Claude Lanzmann's The Last of the Unjust is a DVD Talk Collector Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian and publisher-editor of World Cinema Paradise. His credits include film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||