| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection (The Hustler, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Towering Inferno, The Verdict, more)

Problematic. 20th Century-Fox and MGM Home Video have released Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection, a deceptively good-looking box set containing 13 of Newman's films (on 17 discs), sampling his output from the 1950s through the 1980s. Titles included are: The Long, Hot Summer, Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!, From the Terrace, Exodus, The Hustler - Collector's Edition, Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man, What a Way to Go!, Hombre, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid - Collector's Edition, The Towering Inferno - Collector's Edition, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson, Quintet, and The Verdict - Collector's Edition. In addition, a softbound, 132-page book detailing Newman's career and the films included in this set - copiously illustrated with color and black & white stills, some of which, the box slipcase indicates, have never been published before - has been included as a bonus. To my knowledge, all of these titles and disc extras have been released before on DVD...and that's where one might have trouble with this particular box set. Let's look very briefly at each film (since most of these titles have been covered by other DVDTalk reviewers in the same previous releases), before we discuss the box set itself.

The Long, Hot Summer

Barn-burning stud Ben Quick (Paul Newman), on the road after being run out of his last place of residence, sets his eyes on prim, repressed Clara Varner (Joanne Woodward), who picks him up hitchhiking to Frenchman's Bend, Mississippi - a town wholly owned by Clara's domineering horn-dog father, Will Varner (Orson Welles). Too bad Clara's co-pilot, slutty little minx Eula Varner (Lee Remick), is already taken, married to Clara's weakling brother, Jody (Anthony Franciosa). But Clara will do for Ben's purposes, which include buying some respectability by marrying the uptight wallflower - an act likened almost to animal husbandry by the earthy, "new blood"-seeking Will.SPOILERS' ALERT!

Having seen The Long, Hot Summer numerous times (a while back, AMC seemed to show it about three times a week), I've never understood the critics who treat this film as if it's a bona fide "serious" drama. Perhaps it's the "serious" cast and the "serious" director, Martin Ritt (not exactly known for his comedic touch in his other films), and the fact that it's based on six separate William Faulkner stories - none of which are comedies, per se, that's somehow given the film that reputation. When I watch The Long, Hot Summer, however, I see a full-blown sex comedy which trots out some barely plausible dramatic conventions now and then just for window dressing and to maintain good form. Of course that effect probably wasn't the intention of the filmmakers, but it's hard not to see those elements today in this broadly-played Southern-fried farce, considering the copious double entendres, the constant farcical nature of the bartering for sex between the three couples, and the overall cartoonish tone of the piece. Now don't get me wrong - none of that description is meant as a negative. Like an overripe comic book, The Long, Hot Summer plays better and better the longer it's removed from the context of other self-serious Southern gothic romances of that period. What many critics seem to miss with The Long, Hot Summer, while they're discussing Ritt and the Newmans and Faulkner, is that this film was produced by Jerry Wald; the tone and feel of the film is as much "his" as it is the rest of the cast and crew. From the opening, lilting music by Alex North, with a theme sung by Jimmie Rodgers, and the vast CinemaScope frame filled with gorgeous panoramas of the Southern countryside, a viewer cognizant of Wald's style understands that this is more Peyton Place than Faulkner, with the added pleasure of some pressurized Tex Avery sexual antics crammed into all the slow parts (Franciosa in particular, during his chases of the delectable Remick in nothing but a slip, looks an awful lot like one of Avery's sex-crazed wolves). This is drama-as-Sunday magazine supplement: beautiful color pictures, attractive subjects in the foreground, and tantalizing-but-ultimately empty text filling in the borders. None of The Long, Hot Summer's cornpone dramatizin' is worth a lick if taken seriously; all the whining and declarations from Jody and Ben and Eula (as her father-in-law delicately puts it when the local boys come to bay at the bitch-in-heat Eula: "They don't have to see her, they can smell her."), and Will and Clara don't amount to a hill of unoriginal beans (the appalling chicken-fried Disneyfied ending is a prime example of the film's woefully inadequate, half-baked dramatics). It's only when everyone starts pantin' and heavin', when old goat Will and more-than-willing Minnie (played to perfection by funny Angela Lansbury), mamma's boy Jody and hot mamma Eula, and stud Ben and studiously frosty Clara, constantly negotiate the boundaries of personal and familial politics at the prospect of furious humping, that The Long, Hot Summer takes off and stays an immensely entertaining, funny comedy.

Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!

Domestic strife - and military might - in the toney New England suburbs. In quaint little hamlet, Putnam's Landing, New York public relations man Harry Bannerman (Paul Newman) rarely gets a chance to see his wife, Grace (Joanne Woodward), who is consumed with living the life of a model upper middle-class housewife, which consists of trying to corral her two rambunctious brats in-between meetings for a seemingly endless list of committees. So when town hottie Angela Hoffa (Joan Collins) starts sniffing around for a distraction from her workaholic, possibly violent husband, Oscar (Murvyn Vye), Harry is intrigued...but still faithful. But Grace isn't buying that story, her suspicions aggravated by the fact that her husband has openly sided against her civic duty to her town. You see, Putnam's Landing has been selected by the military for the site of their new top-secret base, and Grace and the townspeople want nothing to do with what they fear might be an atom bomb in their backyards. But what really galls Grace is that reservist Harry has been forced back into uniform by Brig. Gen. W.A. Thorwald (Gale Gordon) - with nasty drunk Capt. Hoxie, played by Jack Carson, personally watching over him - to act as town liaison and P.R. front man for the proposed project.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

I hadn't watched Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys! in years (and it's been even longer since I read Max Shulman's hilarious novel), so I was curious to see how it would hold up (to be honest...I only remembered the luscious Joan Collins in various stages of undress). Unfortunately, what starts off as a promising but unremarkable mixture of domestic romantic comedy and a mild spoof of 50s affluent suburban lifestyle, degenerates badly into a strained out-and-out farce with good actors looking lost amid a sea of unconvincing sight gags and flat comedy lines. There was always a good deal of talk - backed up by Newman's own admission - that broad comedy wasn't the actor's forte, but I found him amusing in most of his scenes here, particularly when he gets to play off the funny, yummy Collins. Their drunk scene together is surprisingly good, with Newman - never an actor who could really "cut loose" physically - agreeably goofy and even boisterous as he yelps and hollers like a refugee from a Warner Bros. Looney Tune as he swings around on Collin's chandelier. I can't say enough about Collins. Not only a drop-dead knockout, Collins has a sly way around a come-hither line; that's a dangerous combination for a comedian. Unfortunately, she's not around on-screen nearly as long as Newman's real-life wife, Joanne Woodward, who seems pinched and irritated here. She could be good in comedy - I adored her as the loud-mouthed, punch-throwing paramour of brawny poet Sean Connery in the seriously underrated A Fine Madness - but her other comedy outings with her husband seemed to find her on off-days. And of course, what more can be said about Tuesday Weld, for my money the single most underrated, underutilized actress of the 1960s? As the gum-chewing, sex-addle-pated teenager Comfort Goodpasture (think about it...), Weld has one of the funniest scenes I've seen in quite some time as she sits across from guitar-strumming Corporal Opie (Tom Gilson), squealing with delight as she barely stops her self from scratching his eyes out with unrestrained teenage lust (George Axelrod, who apparently worked uncredited on Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!, would later use Weld to similar, greater effect in his genuinely weird satirical masterpiece, Lord Love a Duck). Unfortunately, though, she's just a minor character here, and eventually, the lumbering plot must kick in as writer/director Leo McCarey (by this point way past his improvisational prime) grinds on and on, with the final big set-piece - the reenactment of the founding of Putnam's Landing - awkwardly staged. A disappointment after the promising beginning.

From the Terrace

Wealthy Philadelphian iron and steel heir David Alfred Eaton (Paul Newman) wants no part of his father's (Leon Ames) business. Having experienced the horrors of war, and seeing upon his return home how his father hasn't warmed to him in the slightest, David wants to strike out on his own. Samuel, his father, who spurned David because the son he truly loved died young, and who has helped turn his wife, Martha (Myrna Loy), into an alcoholic because of his lack of love, derides Alfred's decision just long enough to tell Alfred why he really doesn't love him, before dropping dead of a heart attack. Freed from his father's crushing, unloving influence, Alfred joins up with rich pal Lex Porter to design aircraft - a nice job for an up-and-comer who landed rich ice queen, Mary St. John (Joanne Woodward). When the aircraft business sputters and dives for Alfred, he conveniently saves the life of mega-wealthy investment banker, James Duncan MacHardie's (Felix Aylmer) grandson, and guess who's on the fast-track to a partnership with the prestigious firm? After years of hard, punishing work away from home, Alfred loses his philandering wife to a former beau, swinger/swapper Dr. Jim Roper (Patrick O'Neal), but finds a soul mate in pretty wildflower-among-the-slag-heaps Natalie Benzinger (Ina Balin). Will success spoil David Alfred Eaton?SPOILERS' ALERT!

Huge and glossy - and most of the time very stupid - From the Terrace nonetheless delivers precisely what its audience expects: high-tone tears as the rich suffer beautifully. Now, I'm well aware that From the Terrace's artistic reputation is less-than-stellar. My buddy Glenn Erickson positively skewered it in a hilariously venomous review that quite honestly, I couldn't find too much fault with...much as I may have liked to, because frankly, I enjoy the film (I disagree with a central point of Glenn's, where he labels Woodward's character a "perfect, loving wife." I'd hardly call the cold, grasping Mary, who demands before she agrees to fully commit to him, that David "do something and be something" - importantly, not "someone - so he'll be "good enough" to take her as a wife, the ideal helpmate). For me, a film like From the Terrace operates on a self-justifying melodramatic, stereotypical plane that the audience knows full well is total hooey...and that's why they love it. This is escapism, pure and simple, a chance to live vicariously for over two hours with pretty people who do nasty things to each other amid the trappings of gorgeously appointed rooms and residences. The question of the morality of the characters, and whether or not the film "sets a good example" for the audience - if such a thing is even possible - is largely beside the point for this kind of cinematic experience. From the Terrace's dramatic structure and characterizations follow rigidly adhered-to, stock melodramatic conventions - the conflicted hero, the cold, distant father, the emotionally devastated mother (who's also a lush), the money-grasping wife, the young, pure, innocent girl with a heart big enough to redeem an adulterer...while committing eventually blameless adultery herself - that viewers of crap like From the Terrace have come to expect with almost welcome affection (as Sandy Dennis says to Richard Burton in the genetic opposite of From the Terrace, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: the best stories are the familiar ones).

A film like From the Terrace allows one to be judgmental - even lopsidedly judgmental - about characters who actually don't deserve two seconds of thought because they aren't much more than cardboard cut-outs...and frankly, who doesn't enjoy being a little judgmental now and then - particularly in a dark movie theatre where we don't answer to anyone else's expectations? Where we're alone with our thoughts, and fantasies? From the Terrace isn't "art," and it isn't a lecture on how to be "good" or "bad" - it's a comic book, if it's anything. A big, gaudy, tacky, morally compromised picture-book that everyone involved with probably paid lip-service to as being "about something" (but which everyone knew was gussied-up junk that wouldn't have fooled a silent movie audience), From the Terrace doesn't have to be "morally clear" or even "right" in its outlook to justify its existence: it just has to move quickly from set-up to pretty set-up while making nice with the audiences' little goofy fantasies about love and power among the rich and, well...the rich. Directed by Mark Robson, who undoubtedly was picked for this project because his similarly-themed exploration of small-town sex among the rich and poor in Peyton Place had been such a socko smash at the box office, From the Terrace features Newman looking almost green around his gaunt gills. He's insufferably smug here, showing little joy of performance in what must have been a career choice based on m-o-n-e-y, but wife Joanne Woodward turns in a nicely brittle performance as the mixed-up Mary (Woodward never looked dishy-er in her cool platinum blonde do and straight black brows), while Ina Balin offers appropriately earthy and soulful brunette succor for poor dopey David. Way too long for a good movie on this subject (which means it's not nearly long enough for this kind of crap), lush, wrong From the Terrace knows its marks, and hits them.

Exodus

In the Karaolos detention camp on the island of Cyprus, American Kitty Fremont (Eva Marie Saint), newly widowed when her war correspondent husband was killed, finds new purpose in life when she meets Jewish concentration camp refugee Karen Hansen (Jill Haworth). After speaking with the British commander of forces on Cyprus, General Sutherland (Sir Ralph Richardson), who makes no bones about his sympathy for the unwanted Jewish refugees, Kitty starts to become involved in the Zionist political struggle to found an independent Israeli nation. Coinciding with this political awakening of Kitty's is her introduction to Ari Ben Canaan (Paul Newman), the grim, charismatic Haganah operative who comes to Cyprus to liberate the latest batch of Jews that sailed to Cyprus and were interned there in British camps. Devising a plan to spirit the hundreds of refugees out of the camp through forged papers, the daring Ari lets the British know that the ship the refugees are on - the Exodus - is loaded with dynamite, and that the Jews aboard will either die of starvation or blow themselves up, unless they're allowed to go to their homeland, Palestine. The ploy eventually works, and the ship sails, but trouble awaits Ari, who becomes involved not only with Kitty, but who also serves as a conduit between his Haganah leader father, Barak (Lee J. Cobb), and his Irgun terrorist uncle, Akiva (David Opatoshu), who is sentenced to hang for a terrorist bombing of a hotel. Emotionally tortured youth, Dov Landau (Sal Mineo), joins the Irgun, and falls in love with young Karen, but their time together may be short once Israel earns its independence, and Arab hostilities escalate.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

A massive, three hour-plus action/drama, Exodus plays best when director Otto Preminger, perhaps the first true American master of the widescreen format, lets cinematographer Sam Leavitt capture several exciting action sequences in sparklingly clear Super Panavision 70 (all of which are for naught in this horrible non-anamorphic transfer for this DVD collection). When Exodus sticks to the action, it's impressive, with Preminger showing a facility for mounting suspense during the excellent blockade sequence at the beginning of the film (the best part of this long, long movie), and the prison breakout sequence in the second half. Unfortunately, everything else in Dalton Trumbo's pedantic script plays off-key, with dialogue that sounds like posturing rather than real people talking to each other, and political discussions that can't help but simplify themes and problems that can't possibly be distilled down into a film ten times longer than Exodus. And I would imagine Preminger, on some level, understood this. If screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, reprieved from the blacklist by Preminger's gutsy decision to openly hired the blackballed writer, wanted to impart a message amid the romance and spectacle, Preminger wisely decided to "blow up" Exodus on the biggest possible screen at the time, using a soon-to-be megastar Newman, and emphasizing the pictorial possibilities of the Super Panavision 70 capabilities (which was in keeping with the late 50s to late 60s preoccupation with huge, road show attractions at the movie houses), to ensure success regardless of whether or not audiences particularly wanted to hear that message. Unfortunately for Exodus, many of the performances are stiffened as well by the iffy dialogue and what one might assume were the filmmakers' attitude and insistence on making an "important film." Newman is utterly humorless here (his character's background may be grim, as well as his duty, but couldn't Newman have found one moment to relay some humanity?), while Eva Marie Saint is, as always, quietly compelling. Sir Ralph Richardson probably gets the most out of doing the least here, while Peter Lawford is appropriately smarmy and obnoxious (he should have stuck with playing villains - he's quite good). Sal Mineo received a lot of kudos for his turn here, getting an Oscar nod in the bargain - and deservedly so. But his partner, Jill Haworth, is useless as the impossibly sweet, angelic Karen. Someone managed to muzzled Lee J. Cobb (a feat for which Preminger should have gotten an Oscar nom, as well), while poor John Derek does what he does best as he essays Taha, the Arab boyhood chum of Ari: get screams with his hopeless thesping. At its very heart a conflicted film, Exodus' visuals outpace its dramatics.

The Hustler

Oakland, California pool hustler "Fast" Eddie Felson (Paul Newman) has one objective, one goal: to play and the beat the best player there is - Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason). He travels to New York with his sad sack manager Charlie Burns (Myron McCormick), and goes to the "Church of the Good Hustler," Ames pool hall. There, he waits for Fats to arrive, and after pleasantries are exchanged - and both players size each other up - the game begins. Eddie shoots a good stick, as Fats observes, but not good enough. As Fats' manager/handler/gambler/gangster, Bert Gordon (George C. Scott), states without a hint of humanity, Eddie's a "born loser." And indeed, Fats eventually hands Eddie his ass, humiliating the young hustler in a display of class and character over superior skills. A break with Charlie finds Eddie on his own, until he meets Sarah Packard (Piper Laurie), a lost soul with a limp who drinks too much and attends college on Tuesdays and Thursdays because she doesn't have anything else to do. Living in a crummy apartment, Sarah knows exactly what "too hungry" Eddie is all about, but she falls for him, anyway - and that's a big mistake. Because Eddie, tired of being a loser, hooks up with the satanic Bert, and Sarah becomes a pawn in the game for Eddie's soul.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

One of those "perfect" films (until the too-literal finale) that seem so difficult to write about, The Hustler still seems so "modern," for lack of a better word, almost fifty years after its original release. Having seen the film too many times now to be surprised by either the plot or the pool sequences (still the best depiction of the sport, particularly when seen next to Scorsese's peripatetic - and empty - approximation in The Hustler's inferior sequel, The Color of Money), what continues to intrigue me now are the subtleties of the performances, and the absolutely dead-on production design that recreates the crummy, seamy underbelly of an urban America that must have been disquieting to mainstream audiences who came to see "the latest Paul Newman film." A quantum leap for the actor after something like From the Terrace the year before, Newman's performance here may be his career best, and it and the film's success finally broke him free of the "popular pretty boy" status he apparently loathed. It's an extremely delicate performance - for a character who doesn't show a lot of delicacy - walking a fine line between young punk braggadocio and sensitive-yet-callow young would-be lover who puts a pool game ahead of the woman who so obviously needs him. It's a startlingly honest performance from Newman, and a very free one from him, too (he could be stiff when trying too hard), before superstardom and a surprising amount of substandard material somehow...hardened him off, closed him off, in later performances. And I'm not sure if any of his co-stars have bettered their showings here, either. Certainly Jackie Gleason, that genuine comic genius (and I don't use that word often or lightly), fulfilled every promise of the dramatic actor he could have been, had he chose to remain solely in that métier (Gleason can say more in a glance in The Hustler than better-known dramatic actors did in their entire careers). George C. Scott, so pin-sharp and acidic in Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder two years before, comes up with his scariest characterization with the reptilian Bert Gordon. Scott, another fine actor who, perhaps like Newman, should have stayed a character actor rather than a leading man, was rarely allowed to play this slitheringly mean again. Piper Laurie always seemed of less interest to me when I was younger, but now I can see what a difficult role she has, and how sensitively Rossen handles what could have been a rather sordid character - one which turns out to be, under Laurie's beautifully modulated performance, a character of great sympathy. The finale of The Hustler has always struck me as too literal, with "Fast" Eddie actually telling Bert he's dead inside. We got that long before director Robert Rossen felt the need to have Eddie tell us so; I just wish the film had trusted the audience a little bit more in not being so obvious. But that's a small point for such a great movie.Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man

19-year-old Nick Adams (Richard Beymer), bursting at the seams to leave the seemingly idyllic but in reality complicated, frustrated life he leads in the wilds of Michigan, suddenly realizes one day that none of his usual activities, like hunting with his loving, timid father, Dr. Adams (Arthur Kennedy), or picnicking with his best girl, Carolyn (Diane Baker), brings him any happiness. It's time to get away from home, away especially from his religiously zealous mother (Jessica Tandy), who cows her un-ambitious husband and treats her grown son as if he's still a boy. Leaving home without telling anyone, Nick soon discovers the perils that await an inexperienced boy lighting out on his own. He comes afoul of a vicious brakeman (Edward Binns) when he hops a train; he befriends a dangerous punch-drunk fighter (Paul Newman); he sees the effects of drugs and alcohol on a P.R. man (Dan Dailey) who can't "slide," he joins the Italian Army during WWI, falls in love, and returns home a changed man, ready to write about his experiences.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

As quiet and thoughtful as his previous Newman picture The Long, Hot Summer was boisterous and crass, director Martin Ritt's Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man was unfairly maligned when it premiered back in 1962, with blame apportioned to not only the cobbled-together script of Hemmingway's Nick Adams short stories, but also to lead Richard Beymer, singled out as a particularly unconvincing evocation of the literary Adams. Fortunately, time has been a lot kinder to Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man. Now removed from the context of premiering just a year after Hemingway's suicide, it doesn't have to "live up" to the actual works of the almost-mythical writer (which the movie shouldn't have had to do back then, either). It can exist on its own, and be judged against similar big-budget, all-star dramas from that in-between time in Hollywood history where the studio system was on its last legs. Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man is far from a perfect film. If anything, it's too short at its present running time (the exact opposite of much 1962 criticism of the picture), with some of the film's "guest star" sequences being entirely too short to have much of an impact (poor Diane Baker suffers the most from this cutting, but Kennedy - brilliant as always - and other good actors like Fred Clark, Dan Dailey, Juano Hernandez, and Ricardo Montalban just get revved up before they're yanked out of sight). I haven't read the Nick Adams stories since college, but I didn't see anything egregious in this adaptation of ten of those stories by Hemingway (indeed, Hemingway was consulted throughout preproduction on this film, with the script being penned by his friend and unofficial adapter for television, A.E. Hotchner). There's a spareness to the dialogue that resembles Hemingway, and if director Martin Ritt can't find equivalent visuals to channel the author's symbolism, he does make Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man look good (through the expert lensing of cinematographer Lee Garmes, on location in Wisconsin and Italy) and sound good (Franz Waxman delivers another beautifully-wrought soundtrack, similar to the quieter passages in his Peyton Place score). Produced by Peyton Place's Jerry Wald (he would die just a week before Ernest Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man premiered), the film has the professional gloss of a Wald picture, but it's relatively restrained and contemplative in comparison to some of Wald's more over-heated CinemaScope melodramas. And that introspective feel created by the soft, evocative lighting (the early scenes of Wisconsin-as-Michigan in autumn are stunningly beautiful) and the reserved dramatics, is further enhanced by Beymer in the lead role. He may not be entirely successful at getting across Nick's youthful naiveté at the beginning of the film, but he's quite good portraying the "changed" Nick towards the end, particularly in his final scene with Tandy, where he rejects her for the final time. As for Newman - since this film is included in this set on the basis of his extended guest shot here - he's nothing short of miraculous in the part of "The Battler." Having played the role several years before in a live TV production, Newman, complete with a rather convincing make-up job (oddly, he looks just like George Segal when he turns his head in close-up that first time...), is scarily in-tune with the addled boxer's fuzzy thinking, creating at the same time a sense of menace in, and pity for, the character in a manner wholly unlike anything Newman had done before in the movies. It's one of the single best bits of acting he ever did during his film career, and, despite the shortness of his screen time here, worthy of being included in this box set.

What a Way to Go!

Pity poor, gorgeous, smoking-hot Louisa May Foster (Shirley MacLaine). She simply can not meet a man without turning him first into a go-getting success...a process which seems to always lead to her husbands' untimely deaths, and her geometrically-expanding bank balance. Growing up poor in Crawleyville, Ohio, Louisa May rejects the advances of slimy town rich boy, Leonard Crawley (Dean Martin), only to go off with determined failure Edgard Hopper (Dick Van Dyke). Only he doesn't stay a failure for long, and soon Louisa May is a young widow with a nice inheritance. Fleeing to Paris with her grief, she meets "starving artist" Larry Flint (Paul Newman), but a tiny suggestion about the way Larry paints leads to more heartache...and more money. A dalliance with cold, bored multi-millionaire Rod Anderson, Jr. (Robert Mitchum) winds up with Louisa May convincing him to give up all his dough and retire to a farm...with disastrous results. Terrible song-and-dance man Pinky Benson (Gene Kelly) is next: one minute a flop, and then under Louisa May's tutelage, a huge star, and then a corpse. Will her shrink, Dr. Victor Stephanson (Bob Cummings), being able to help her...or marry her?

SPOILERS' ALERT!

A downright perverse "Lush Budgett" production, director J. Lee Thompson's What a Way to Go! has scattered guffaws during its run time, and it gets kudos for chutzpah alone in corralling all those big names in the service of propping up the one-joke premise in this disgustingly expensive sex comedy. But overall...it's hit-and-miss. Originally intended as a Marilyn Monroe production (that doesn't mean it would have been better), this star-packed "project" plays like It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World Meets Doris Day, with the obvious black comedy sex elements blown up to gargantuan proportions through the casting, the copious costume changes by Edith Head, and the reliance on the audience's gorping at all this excess to cover the fact that the jokes aren't all that strong (case in point: Dr. Bob Cummings tells MacLaine, "You don't need a psychiatrist, you need your head examined." Scream). Spoofing the very kind of movie it is, there are some moments in What a Way to Go! that seem like they'll transcend the obvious satirical jibes, such as the marvelously presentational sequence where Thompson spoofs "lush budgets" Hollywood films. Abandoning all pretense of the conventional narrative structure, Thompson just keeps backing up the camera and letting luscious MacLaine strut around in one outrageous Edith Head concoction after another, eventually topping himself by showing Mitchum and MacLaine in bed...inside a giant champagne glass. Had What a Way to Go! maintained that level of unconventionality throughout its structure, it might have transcended its thoroughly familiar themes. Unfortunately, most of the film plays too close to the rules of this kind of all-star spectacle (get the star on, get him off), with the viewer eventually seeing that many of the stars here are ill-served, as well. Bob Cummings "opens" the film, but really has nothing to do (for that matter, book-ending Dean Martin doesn't, either). Van Dyke shows exactly why his big-screen career never eclipsed his television resume (in his "straight" scenes, he comes off flat and slightly grumpy, until he does his standard "silent movie" routine). Mitchum could not be any more bored (although he does get the film's biggest laugh with the classic, "Melrose, for-give me!" bull scene). Gene Kelly has a terrific dance number with MacLaine, where they channel everything from Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell, to Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, to...well, Gene Kelly, and he's fine as the obnoxious big-deal Pinky. Paul Newman probably comes off best, though, putting a lot of bravado into his genuinely funny starving artist character (only when he puts on that British upper-crust accent at the end does he fail - he could never pull off that attitude of sneering spoof). As for poor Shirley MacLaine, she's unfortunately overwhelmed by the sets, the costumes and her co-stars. While her marvelous dancer's body is frequently - and thankfully - on display here (that black bikini, man...), What a Way to Go! doesn't give her much opportunity to actually create a character, and that's too bad, considering how often her unique personality was misused in films (once she hit it big with The Apartment, Hollywood didn't know what the hell to do with her). And ultimately, that lack of a strong central character only points out how empty What a Way to Go! is at its core...which would be fine, if only the jokes were funnier.

Hombre

John Russell (Paul Newman), a white man once captured by the Apache as a boy, brought back and raised white, only to willingly escape again back to the Apache, is tracked down, living in the hills, and told by young Billy Lee Blake (Peter Lazer) that he has inherited a boardinghouse in town from the white man who raised him. Russell, who thinks of himself as Indian, dislikes whites for their treatment of his people, and has no intention of keeping the boardinghouse, essentially throwing out Jessie (Diane Cilento), who managed the place. Jessie, with nowhere else to go, asks sometime lover Frank Braden (Cameron Mitchell) if he'll marry her; he declines. So she's leaving town, as is Russell, Billy Lee and his fickle, spoiled wife Doris (Margaret Blye), and Indian agent Dr. Alex Favor (Fredric March) and his high-toned wife, Audra (Barbara Rush). But the regular stage coach run is closing up shop with the coming of the railroad, so the stage's agent, Henry Mendez (Martin Balsam), is paid by Favor to organize a makeshift run, and Mendez wants Russell to help out. There's only one problem: bad man Cicero Grimes (Richard Boone) wants on the stage, as well.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

A grim chamber piece Western taken from an Elmore Leonard novel and adapted by director Martin Ritt's frequent scripters, Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Hombre seems like it should be a big, rousing, "modern" Western with that cast and story, and with the colorful, big-screen production values typical of a studio "A" Western from that time (the original trailer certainly sells the picture as action-packed and macho). However, it plays remarkably quiet; there's a stillness to Hombre, reflected in Newman's largely silent role, that transcends the few action moments in the script. This film is about relationships - both societal and personal - with the gunplay only added in small doses to keep the viewer aware that in such an unforgiving landscape as the transformational Old West, your views could get you killed. Hombre's hook is turning the traditional Western hero image upside down. Russell is white, but he considers himself Indian. Russell is the strong, silent type...and remains that way, never truly revealing his intentions even at the end of the film (as opposed to most Western heroes who eventually put their personal credos into words). And most importantly, Russell isn't the slightest bit interested in helping others through altruistic intentions; the little band of people that cling to him for protection, do so at their own invitation, not his. He hates whites, and the hypocrisy he sees among his fellow travelers doesn't change that opinion one bit (of course, it's admittedly a stacked deck here, since Ritt only presents the whites as failed human beings).

It's a remarkably unforgiving character throughout the film, one the audience can't warm to in the slightest (indeed, no one is very likeable here, except for possibly Cilento, while Boone has a field day as a grunting, scurrilous villain). And to Newman's credit, he manages to snuff out almost all of the vestiges of his own personal magnetism here, creating a compromised anti-hero that most viewers wouldn't want to ever meet (something that director Ritt and Newman couldn't pull off in Hud - a genuine sonafabitch character that women, nonetheless, desired, and men wanted to emulate). Every encounter in Hombre is marked by tension and ultimately, betrayal, and those moments feel honest and spare, with dialogue that cuts out the b.s. and gets right at it: people screw each other over, time and time again, not just because of race (the film's most obvious catalyst), but because of everything, including economics and personal desires and frustrations. And yet, precisely because of Hombre's seemingly unrelenting pessimism, I'm not sure the ending works, where apparently, Diane Cilento "gets through" to Newman, and he decides to finally help the travelers, knowing full well it will mean his death. Why does Russell do this? The scene is played too short and pat, with Newman not giving a whole lot away, for us to get a sufficient bead on the reason, so we have to conclude: he finally saw the light. But that flies in the face of everything that was different, and frankly invigorating, about the character to begin with. Yes, Russell dies a useless death, and that fits with the general cynicism of the piece, but he does so in the service of others, and that message is far too conventional for a film like Hombre.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Old West bank robbers extraordinaire Butch Cassidy (Paul Newman) and the Sundance Kid (Robert Redford) didn't count on their gang, The Hole-in-the-Wall gang, being dissatisfied with Butch's leadership. Challenged by gang member Harvey Logan (Ted Cassidy), outmatched Butch easily beats the giant Harvey in a knife fight by unconventional means: he cheats, with an unanticipated kick to the groin. His leadership reaffirmed, Butch plans on robbing the same Union Pacific Flyer twice, which works the first time but goes disastrously wrong the second. This second robbery is the last straw for the railroads, and a special posse is rounded up to kill the easy-going Butch and the deadly Sundance. On the run with the woman they both love, Etta Place (Katherine Ross), the trio eventually escape to Bolivia, where their bank-robbing ways spell further trouble

SPOILERS' ALERT!

A massive hit when first released (as well as on many re-releases at drive-ins and on TV), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid became one of (if not the) Newman's signature films. I don't know where it stands today with younger audiences - if they're even aware of its impact on the industry and audiences back in 1969 - but it certainly did help evolve the Western and the comedy genre. Not an out-and-out spoof like the Oscar-winning Cat Ballou, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was satirical, but in a hip, smart-assed way that really more resembled that other influential black comedy from two years before, Bonnie and Clyde. Expanding on that film's comedy-of-violence theme, while toning down any hint of tragedy (until the end) in favor of romance (complete with Burt Bacharach melodies), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid tapped into that deliberately anachronistic goofing on a genre that appealed to younger audiences, while the star power of Newman and the promise of a "funny" western with some naughty moments (Newman kicking someone in the balls; Redford yelling, "Shit!" as they jump off the cliff into the river), sold tickets to every age group. Like other popular Newman titles, I've watched Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid too many times to come at it like a viewer fresh to the experience would, so inevitably, the film's signature scenes don't pack the punch they once did for me. But the film's pervasive tone of nostalgia and funny/sad romance work quite well after repeated viewings, taking a more prominent position now in the film than how I remembered them as a kid. Newman and Ross (seriously beautiful here) have some tender, funny, sweet moments together (the celebrated bicycle ride to Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head is brilliantly done), and one wishes that the film could have paused longer on this element of the film rather than rush back constantly to the "Boys' Own" adventures with Redford goading on Newman. Redford, for my money, was never funnier than here (one wonders what the chemistry in the film would have been like if Newman had had his way and signed Steve McQueen as his co-star?), but not enough is done with his relationship with Ella to balance out the Newman/Ross scenes (perhaps as a result of Newman's star weight?). Still, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid achieves an elegiac tone that, mixed with it humorous performances and its kinetic/spoofy action sequences, keeps it fresh even forty years (!) after its premiere.

The Towering Inferno

Terror awaits the various people who find themselves at San Francisco's newly-built, spectacular Glass Tower on the night of its dedication. The Tower's architect, Doug Roberts (Paul Newman), having just designed the world's tallest structure, decides he's had enough of the rat race of planning multi-million dollar buildings - he's getting out and moving to Oregon, a move that doesn't please his successful magazine editor girlfriend, Susan (Faye Dunaway), who's just been offered a plum job. Jim Duncan (William Holden), the Tower's builder and money man, is justifiably proud of the world-famous structure, and he plans on enjoying every minute of the star-studded celebration that night which will include guests such as Senator Gary Parker (Robert Vaughn). But trouble is brewing in the Tower when several electrical overloads clue-in Doug that Duncan's weasely son-in-law, Roger Simmons (Richard Chamberlain), may have cut corners in the construction of the building - design compromises the power-hungry Tower can't take without bursting into flames. Which is exactly what does happen when a small fire in a janitor's closet turns into a night of blazing suspense (as the ad copy went). A call to the fire department brings Fire Chief Michael O'Hallorhan (Steve McQueen) to the scene, and the race is on to save the various attractive people trapped in the Glass Tower.

SPOILERS' ALERT!

Another Newman classic that still works, decades later. Who can say which disaster film was the king of the genre during its golden age in the 70s? It's always going to be a debate (Airport was the classiest; The Poseidon Adventure had the most Oscar winners, with Hackman, Borgnine, Winters, Albertson, and Buttons screaming at each other; crappy Earthquake was spectacularly redeemed by Charlton Heston and Sensurround). But for sheer star wattage (Newman and McQueen were the two biggest male movie stars on the planet in 1974, while Dunaway was no slouch at the box office, either - a coup for the lowly disaster genre), for epic length (it's the longest of the 70s disaster flicks), and for spectacular production design and special effects, I don't think any other disaster film touches The Towering Inferno. The sheer size of the project, not just in length and production values, but in the weight of its cast (featuring many actors far too good for this type of film), give The Towering Inferno a sizeable heft you just don't experience with any other disaster picture from that era. Producer Irwin Allen gets most of the credit for The Towering Inferno, but director John Guillermin's (The Blue Max) contributions shouldn't be ignored, either (just look at the later films Allen directed on his own for comparison). No one is going applaud the film's script; the dialogue, when not focused on the technical, often sounds labored and forced (when Newman the Rebel Architect says he's going to quit the rat race and "sleep like a winner," I get the giggles). But there is an inexorable build-up of the suspense as we get to the film's most elemental theme: who will live, and who will die. Some critics call that intention exploitative and crass, with the audience encouraged to enjoy the next death by fire or falling or explosion. But how is The Towering Inferno's death watch any different than Spielberg's deliberate teasing for the next shark attack in Jaws? Nobody calls Jaws anything but a masterpiece, but its main delivery system is the same: showing the audience various spectacular, gory deaths. Enough defensive carping. Highlights include O.J. "It was Nicole's fault" Simpson badly pretending to ward off the heat and smoke, waving his hands comically in full close-up, no less; Susan Blakely looking gorgeous as she cries (no one has ever looked more attractive on the big screen, tearing up, with her little red nose); Richard Chamberlain pushing people out of windows to save himself, and Robert Vaughn being Robert Vaughn. As for Newman and McQueen...Newman takes the unusual position of getting pushed around a bit by the ticked-off McQueen (Newman seems to take it in stride -- he's almost bemused in some scenes), while McQueen looks...a little seedy, to be honest (this was right before he virtually became a hermit, gaining a lot of weight and disappearing from movie screens for quite some time). Still, they make a great team (pity about Butch Cassidy), and the film delivers the disaster genre goods.

Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson

1885. William "Buffalo Bill" Cody (Paul Newman) anxiously awaits the coming of the latest, big-name attraction to his Wild West show: Chief Sitting Bull (Frank Kaquitts). Vain charlatan Cody, who wears a wig and puts peppershot in his pistols to always hit his marks, is no longer an individual with claims to the settling of the West; he's the head of a show business corporation, and as such, the "truth" about the West and his role in its settling, is secondary to putting on a good show for the paying customers. His entourage encourages his self-delusions about himself, but those illusions are shattered when Chief Sitting Bull refuses to play Cody's game of show business over the truth.SPOILERS' ALERT!

Based on the controversial Broadway play Indians by Arthur Kopit, Robert Altman's Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson was famously panned when it came out during America's Bicentennial in 1976, with audiences staying away in droves, too, putting a serious dent in both Newman's and Altman's later career trajectory. While many critics felt the film picked the wrong time to attack one of America's cherished myths about itself and in the process, alienating an audience that genuinely wanted to celebrate what was good about the country (and there may be some truth to that, considering that America was just starting to come out of the cycle of the late 60s, early 70s pop culture that delighted in knocking itself), that can't explain the critics' reaction. The mostly left-wing-leaning critics have always made room for films that attack American institutions, so why didn't they enjoy Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson more? Watching the film in this inferior flat widescreen transfer (I haven't seen the film since it came out), what struck me was the lack of "Altmanesque" touches that make his other films visually and just as importantly, aurally, so interesting. Altman largely abandons his zoom lens from a mile back, open framing that let characters come in and out seemingly at random, while also 86ing his multi-track audio construction that was uniquely his. Instead, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson is shot in a rather conventional, straight-ahead manner that makes us focus more on the story...and that's not to the film's advantage here. I found some of Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson quite amusing, particularly Pat McCormick's turn as Grover Cleveland, and the marvelously animated Kevin McCarthy as publicist Major John Burke. But what points Altman has to make about the mythologizing of the West, and the differences between White and Indian culture, he makes early...and then just keeps repeating them over and over again. It doesn't help that he makes a cipher out Chief Sitting Bull, who's supposed to be the catalyst of dissension among Cody's group, nor does it help that Newman doesn't vary his performance. There's no build here, no arc to the character. Newman turns the dial to "buffoon," and keeps it there throughout the remainder of the film. It doesn't particularly matter that Altman takes a figure from history that was in actuality quite contrary to how he presents him here - although it would have mattered to critics if a filmmaker had done the same thing to a politically left-of-center character (Cody was actually a strong proponent of Indian rights, as well as women's, and his efforts to bring a positive view of Indian culture to Whites were among the first). Altman has that right of satirical reinterpretation, but if he wanted to make a film that engages us past its opening themes, he didn't have the right to make Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson so one-note and surprisingly conventional.Quintet

In a frozen wasteland that could be Earth, wild dogs roam the ice, eating the corpses of the few remaining survivors of whatever calamity befell the planet. Out of this no man's land comes Essex (Paul Newman), a self-proclaimed seal hunter with his mate, Vivia (Brigitte Fossey), who is carrying his child. Arriving at the old city/apartment complex he used to live at, Essex wants to meet up with his brother, Francha (Tom Hill), whom he hasn't seen for years. Obtaining an ice-covered apartment from Deuca (Nina Van Pallandt), Essex rejoins Francha and his family, but during a trip to buy firewood, he sees Francha's apartment blown up, with everyone inside killed, including Essex's wife and baby. Essex sees that it was Redstone (Craig Richard Nelson) who threw the bomb, but before Essex can kill him, Saint Christopher (Vittorio Gassman) slits Redstone's throat, and soon Essex realizes that a real-life game of Quintet - the board game where hunter kills hunted - is being played out at the apartment complex.SPOILERS' ALERT!

Simply put: the worst film of Newman's - and director Robert Altman's (and that's saying something) - career. I distinctly remember catching Quintet in a deserted theatre back in 1979, and wondering what the hell it was I was sitting through. That feeling has only intensified thirty years later. I guess the biggest question one might have about Quintet is: what, exactly, did Newman see in the project to go ahead and accept the starring role? By 1978, when the movie was in production, Altman had been on the skids both critically and at the box office for years; didn't that prospect of hooking up with Altman give Newman pause, particularly after their last joint outing, Buffalo Bill, proved to be such a disaster at the box office? Newman at this point was coasting on the success of Slap Shot the year before, but a consistent string of hits eluded him; for every The Towering Inferno or The Sting in the 70s, there were more b.o. disappointments like The Mackintosh Man, Pocket Money, or The Drowning Pool. Was Newman hoping against hope to cash in on the sci-fi genre, renewed by Star Wars the previous year? Perhaps. But whatever the reason, Quintet clearly shows the actor in a bad light.

The film itself is frequently ridiculous. Altman wants us to believe this nether world of ice - which is unconvincingly staged in the cramped, boring Man and His World pavilion left over from the rotting Expo '67 displays in Montreal - is ruled by the game of Quintet, a board game that has captivated the few survivors of the world to the point where they'll actually kill each other to act out its moves. Fine. Sounds intriguing. So...how about explaining the goddamned game to us, Robert? Did no one see this huge blunder during production? We see a few snatches here and there of the game being played; we hear some nonsensical rules out of context, and that's it. We're supposed to care about these characters and this world supposedly infused with the spirit of Quintet - after all, that's the film's main metaphor...without ever actually understanding the game, or seeing it fully played? Would it have been so hard to shoot just two minutes of explanation, so we could actually get into the play of the game, and therefore the film? If the movie had been called Parcheesi or Chutes and Ladders, I wouldn't have needed any background ("Ha, Essex! I've got a five! Slide down the ladder so I can slit your throat!"), but if you're going to invent a whole new game and base a movie on it, how about letting the audience in on the whole thing (the similarly structured Rollerball certainly got that concept)? The entire film operates that way, keeping its secrets and feelings so close to its vest, we eventually give up and start laughing at the inane, pseudo-intellectual claptrap that passes for dialogue here. Characters talk about how things used to be, and death, and the void of existence, and all the audience wants to do is chuck a snowball at someone's head and yell, "Shut yer trap!" My god is Quintet a pompous, phoney load of shit, with its self-serious European co-stars skulking around icy corridors, mumbling asinine incantations about death while sucking their thumbs (yes, they do that in the film), and its deliberately fuzzy thinking (and while we're on fuzzy: clear the Vaseline off the lenses, dimwits - it doesn't make me think of ice; it makes me think I'm watching Quintet at the drive-in through a fogged-up windshield). As for Newman...he looks terrible here. It's a startling transformation for the actor when you see him just three years before in Altman's Buffalo Bill. He looks as if he's aged 15 years. And trust me: the frozen sets have nothing on Newman's personality here. He looks mortified to be in this junk - he had to have known from day one that Quintet was a loser. Gravelly-voiced, washed-out, and clearly exhausted, Newman the superstar looks just plain tired. Newman was fond of saying The Silver Chalice was the worst film he ever made. I often thought he said that as a preemptive strike against the few unlucky souls who managed to catch Quintet.

The Verdict

Alcoholic ambulance chaser Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) is at the absolute end of his rope. Given a piece-of-cake "moneymaker" case by friend Mickey Morissey (Jack Warden), all Galvin has to do is show up at the office of the Boston Catholic dioceses and accept a settlement check from Bishop Brophy (Edward Binns). It seems a young girl was given the wrong anesthetic at a Catholic charity hospital when she came in for routine surgery three years before, and now the girl's sister wants to settle with the Church and move away with her husband. The Church wants the whole matter settled without publicity; Mickey wants Galvin to get a hefty commission under his belt so he can finally wash his hands of the pathetic alcoholic, and Galvin wants something, anything to go right in his life after a downward spiral that saw his reputation and career and family life ruined. But a moment of clarity, an epiphany if you will, between Galvin and his vegetative client makes him turn down the easy money, and pursue the case...which is a big mistake, as he'll be going up against "The Prince of Darkness" attorney, Ed Concannon (James Mason).

SPOILERS' ALERT!

A late career triumph for Newman and director Sidney Lumet, with a hard, lean, uncompromising script by the brilliant David Mamet, The Verdict looks better and better over 25 years after its premiere back in 1982. On a par with Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder and Wilder's Witness for the Prosecution, The Verdict may, ultimately, not surprise viewers with its ending (we all know how it's going to end; we're just not sure how Mamet and Lumet and Newman are going to get there), but Lumet has such a sure handle on Galvin's background and context scenes (the dread-filled opening sequence with Newman spiraling down have an almost operatic grandiosity) that we're constantly surprised at the layering he's able to convey - helped of course by Newman's performance (to my mind, his best). Not at all afraid to initially jettison all the tricks big stars use to ingratiate themselves with the audience, Newman's alcoholic loser is frighteningly real, and not at all superficially "showy." It's an exhilarating performance from a "big star." The supporting cast is superlative, as well, with a mixture of big-name heavies like Charlotte Rampling (another dense performance) and the effortlessly vampiric Mason, and Lumet stage actors like Milo O'Shea, Lindsay Crouse, and Roxanne Hart. A beautifully integrated drama, where all the elements come together seamlessly.

Having watched all of the films in the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection, there's no question it's an interesting gathering of some of Newman's best - and not so great - work. Several of the titles are career highs for the actor in their respective genres: The Hustler and The Verdict for drama; Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid for comedy and westerns, and The Towering Inferno for action. The other titles, to varying degrees, show Newman to good advantage (Hombre, The Long, Hot Summer), or mired in less-than-optimal projects (Quintet takes the cake). Of course, the realities of 20th Century-Fox and MGM releasing this collection make it impossible for equally worthy films to be included here (three of my favorite Newman performances, in Harper, Cool Hand Luke and Pocket Money, are owned by Warner Bros. and have been released in their own collection), while we're still waiting for someone to release other M.I.A. Newman titles - where's Sometimes a Great Notion? Or W.U.S.A.? At this point, I'd even watch The Secret War of Harry Frigg before I'd watch Cool Hand Luke for the 87th time, just for something different.

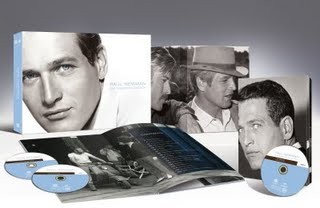

Getting right to the heart of it then, the bonus book included in the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection box set is the only new element the DVD collector needs to consider when deciding on a possible purchase. All of these titles have already been released on DVD, and importantly, the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection utilizes the exact same transfers for these discs - including the two non-anamorphic, flat letterboxed transfers for Exodus and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (only the discs' artwork is new - they all have the same plain blue-and-white color scheme, and the same unifying font for the titles). Those films look absolutely terrible here, while the remastered special collector editions (complete with second discs of extras) of The Hustler, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and The Verdict look phenomenal (all of the other titles look quite dishy in their brightly-colored, sharp anamorphic transfers). All of the on-disc bonuses included here appear to be the same ones found on the previous releases (we don't have any of the supplemental bonuses from the "Collector's Edition" titles here, such as the miniature lobby cards found on the original The Towering Inferno Collector's Edition disc set, for example). So, for the collector who already owns some or all of these titles, the new softcover book is the only new bonus to factor in for a double-dip. There are no credits given whatsoever for the 10 ¾ x 7 ½ softcover book (no author is listed, nor any publishing information - only citations for quoted material), so I'm going to assume it was written specifically for this box set. There's certainly nothing in the book's text that will come as a surprise to anyone who's read up on Newman. Arranged chronologically by each film title included in the set, we get some tidbits about Newman's life and career during the making of each film, along with some behind-the-scenes info on the movie's production, and its critical and box office reception - and none of this info is particularly in-depth (although the book is honest in its rundown of the films, noting the negative receptions of some of the films). At the end of the book, the titles are again listed (illustrated with original poster art), with some critics' snipes as well as a listing of the on-disc bonuses found for each title (so you either have to refer to this book to tell what extras are on a particular film, or pop in the disc - they're not listed anywhere else). The photographs are fascinating (many of them candid, behind-the-scenes shots), and they're assembled with care; it's a nicely-designed softcover book. One interesting note: on the final two pages, the films are again printed within a box grid, with full credits listed (probably for legal reasons). However, three boxes at the end are blank - were three other films planed for the set, and then dropped?

Other than the obvious appeal of the films themselves, the bonus softcover book is the biggest check in the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection box set's "plus" column. However, there are some serious drawbacks to this collection, as well. Obviously, the two old, non-anamorphic letterboxed transfers for Exodus and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson are the set's most egregious offenders. To put it bluntly, it is simply unacceptable in 2009 for a studio to release a pricey, multi-title commemorative box set that recycles ancient, non-anamorphic, "flat" letterboxed transfers. The days of consumers not being able to tell the difference between the two formats are long gone now that large widescreen monitors are so prevalent. My mother still doesn't understand my explanations of what exactly an anamorphic transfer is, but she can see with her own eyes that the Exodus disc she bought years ago - the same transfer that is used here in the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection - looks subpar on her new brand-new 48-inch monitor. If Fox and MGM didn't want to pay for new anamorphic transfers for these films, it would have been better to leave them out of the collection altogether.

The other major problem with the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection is the packaging. When I first took hold of the 11 x 8 box set in the mail box, appreciation for the striking box graphics turned immediately to horror as I turned the box over to read the back: the unmistakable sounds of loose discs could be heard within the baby-blue box. A lot of loose discs. Pulling away the shrink wrap, the heavy interior cardboard file folder slipped easily out of its thicker cardboard slipcase (oriented horizontally), with the bonus book neatly tucked open pages-down in the file folder. However, after extracting the two illustrated, multi-fold cardboard disc holders out of the file folder, I found all but two of the seventeen discs had dislodged from their cardboard slit holders, with several of them badly scratched. Much to my annoyance, I eventually had to buff out six of the films to fix them from freezing - while two other titles were apparently beyond saving (luckily, I already had them in my collection). Cardboard slit holders have to be the single worst method of storing discs I've encountered. Usually with these holders, the edges of the cardboard are rough, and the slits so tight, that you have to dig and pinch to get the discs out (plenty of fingerprints), while the rough edges continue to damage the playing surfaces of the discs as they go in and out. At least, however, with earlier cardboard slit holders I've had, the slit enveloped at least half of the disc - they may get scratched, but they're not going anywhere for awhile. In the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection, however, someone had the bright idea of making the slits less deep (perhaps to offset the work it takes to dig and pinch the discs out?), which of course lessens considerably the cardboard holding power on the discs - hence, my boxful of loose discs (the slits only cover the bottom ¼ of the disc - not nearly enough friction). I'm sorry, but for a relatively expensive gift set featuring second-hand transfers and a puff-piece picture book as the main selling points, the studio should at least make sure the goddamned discs are going to stay put during shipping. Anyone who decides to purchase the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection should invest in some clear plastic holders for the discs, and just put away all this expensive-looking but poorly-designed cardboard packaging as a souvenir.

Final Thoughts:

Nobody wanted to give the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection box set a "DVD Talk Collectors Series" rating more than me. He's always been one of my favorite actors and movie stars, and the timing of this commemorative set feels right, considering his recent death. But along with the handful of bona fide classic Newman titles included here, there are a few movies in the collection that do little or no favors for the actor. Even worse, two of the films presented here utilize out-of-date, poor-looking non-anamorphic transfers - simply unacceptable in this day and age for an upscale commemorative box set. Add to that misstep the poorly-designed packaging, and you had better want that photo-stuffed softcover book badly to double-dip on this problematic release. Netflix isn't going to send you the book if you rent the set (or at least I don't think they will), so a "rental" recommendation seems iffy. However...the classics that are included here are as good as you can get within their genres, and when Newman fit his character, nobody could touch him. So...it may make a nice Christmas gift for the undiscriminating Newman fan. Serious collectors, though, should absolutely skip the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection, but general audiences may rent a few titles to see if they can live with the gift set's drawbacks. So, that's a recommended, skip and a rental for the Paul Newman: The Tribute Collection, depending on your needs.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||