|

|

|

|

Lillian Ross's book Picture is a production journal about John Huston's The Red Badge of Courage. Ross is unforgiving with the various assistants, associates and yes-men hovering around the front office. Producer Gottfried Reihhardt had directing ambitions of his own; he's considered the tasteful, quiet one likely to make prestige pictures for MGM. But the actual adaptor of Stephen Crane's book, 26 year-old Albert Band, was kept on as a production assistant. Ms. Ross notes that when around the heavy hitters, one of the authors of the screenplay is treated like a gopher, and his opinions ignored or belittled.

But Albert Band's drive and ambition weren't curbed by Lillian Ross's slights. With his writing partner Louis Garfinkle, he made a low budget western with Russ Tamblyn and an equally cheap horror picture with Richard Boone. Then, as if re-channeling all the lessons of quality filmmaking he had observed with Huston and Gottfried, Band adapted another Stephen Crane story. He then took a group of American actors to Sweden, to work in conjunction with the same production company that made Ingmar Bergman's films. This was interesting thinking for the time: various cheapjack American producers would film in Europe mainly to save money and continental production companies wanted into the U.S. market. By co-producing with a Swedish company, Albert Band could make a much classier film than his previous efforts.

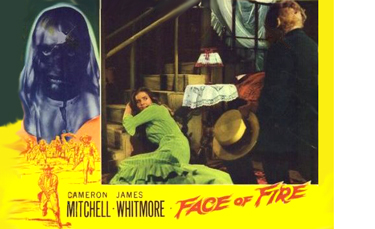

Although marketed in 1959 as yet another horror item Face of Fire is the work of a director looking to break into the art film world. The solid drama closely follows Crane's novella "The Monster". The disfigurement of a popular fellow in a small town becomes an early social comment piece, the 'monster' being the town itself. Band does some clever reverse casting. Former Fox contractee Cameron Mitchell is most remembered for playing villains, the hero's crooked associate or less-than-couth guys that try to rape the leading lady: Hell and High Water, Garden of Evil, No Down Payment. For Face of Fire Mitchell is the ethical, conscience-stricken leading man. James Whitmore had been a respected star back at MGM, playing tough soldiers but also producer Dore Schary's liberal notion of the common man. He was adjudged a less-handsome Spencer Tracy. Band uses Whitmore as the snappiest guy in town, the one the women go for. With just a broad smile and an air of self-confidence, the actor convinces us that he's the 1898 equivalent of date bait. Another noted actor Band

The story reminds as much of Henrik Ibsen as Stephen Crane. Doctor Ned Trescott (Cameron Mitchell) is happily married to the respected Grace (Bettye Ackerman) and is raising a fine boy, Jimmie (Miko Oscard). His handyman and good friend Monk Johnson (James Whitmore) reformed eight years before and is now one of the most liked and admired men in their small New York town, Whilomville. Then Monk and Jimmie are caught in a fire that burns the Doctor's house. Monk brings Jimmie through the flames but his mind is affected and his face destroyed by chemicals in the doctor's laboratory. Trescott and The Judge (Robert Simon) discuss whether the mindless, incommunicative Monk would rather be dead. Determined to care for the man who saved his boy, Ned hires local drunk Al Williams (Richard Erdman of Cry Danger!) to take care of him. The gossip about Dr. Trescott harboring a dangerous 'monster' gets out of hand when the childlike and uncomprehending Monk escapes his room and wanders downtown. People panic. He looks in a window at a birthday party, frightening the children. The adults exaggerate everything. Whilomville's most prejudiced mother Ethel Winter (Lois Maxwell of Dr. No) turns especially vicious. She demands that her henpecked husband Jake (Royal Dano) lead a 'search' party, but really expects Monk to be shot dead.

In Stephen Crane's original story Monk Johnson was a black man, which changes everything completely including the ending. The racial switch technically places Face of Fire among liberal issue movies that felt it necessary to compromise their own themes -- Pinky, Lost Boundaries. Biographers note that Crane witnessed a lynching when a small boy. Actor James Whitmore followed up this unusual role by playing the lead in Black Like Me, a white journalist who changes his appearance to pass for black. The coincidence would seem fairly ironic. Sold as a horror movie, Face of Fire had a brief, almost invisible theatrical release. It had unlikely commercial prospects at a time when socially conscious filmmaking was limited to more scandalous, topical subject matter, like Robert Wise's I Want to Live! A generic variation on the Lynching movie, it shows rural small-mindedness and hypocrisy in bold relief. Disfigurement is unpleasant, something people don't like having around. Lois Maxwell's bitter and abusive Ethel (right) already tortures her husband. Because Monk Johnson made her little girl cry she expects him to be hunted down and killed at her say-so. Two of Dr. Trescott's female patients have had no contact with Monk whatsoever, but work themselves into a fury of hatred, which spills over onto Trescott as well. Poor Monk is out of luck, plain and simple. He's mentally incapable of understanding what's happened to him. Monk had passed up the potentially 'fast' girls in town to sit in the parlor of his steady girl, the devout Bella Kovac (Jill Donohue). Now Bella can't handle him. When his presence reduces her to tears, the townspeople jump to the conclusion that Monk is a potentially murdering menace. At one point in the picture he's believed to be dead, and the whole town turns out to mourn the fellow that had been the most popular man in town. Then Monk turns up alive, and is again branded an unholy menace. Like the unhappy hero of Ibsen's An Enemy of the People, Ned Trescott is boycotted by his patients for not disposing of the Monk-monster. It's an excellent illustration of the truth that, when given the chance to behave as a mob, People Are No Damn Good.

Face of Fire no longer seems as obscure as it once did. The only giveaway for the foreign filming location are couple of actors that seem too 'Swedish,' including the boy who plays Ned Trescott's son. Director Band would seem to have been a literate movie fan, as a few touches remind us of Charles Laughton's much more stylized The Night of the Hunter: children singing, the framing of shots of a porch conversation. The general look of the film reminds us of Arthur Penn's later The Miracle Worker -- the rural setting, the soft light, the period costumes. Band's direction takes advantage of the higher level of production afforded by the Swedish facilities. He doesn't need to limit his camera angles; he uses a crane several times to good advantage. Cameron Mitchell must have been disappointed when this show received such a spotty release, garnering little attention. His fine performance overshadows a lot of genre pictures where he was asked to play not very interesting characters. The situation reminds some of The Elephant Man, but Dr. Trescott is not trying to exploit Monk's freakish condition. Not much later Cameron began working frequently in Europe, splitting his time between Italian action films and Television projects back in the States. Of the other actors, the career of English talent Lois Maxwell seems especially adventurous, with 1950s credits spread across the map from Hollywood to Italy. She seemed attracted to unusual roles -- did Face of Fire represent a challenge, an opportunity to spend time in Sweden, or just a chance to escape from London based TV work?

What does Face of Fire lack? It makes its points quite well. The monster angle on the posters -- "Would you Dare to Lift the Mask?" -- can't satisfy because Band and Whitmore don't go for the usual 'shock' horror reveals or monster effects. Even during his misadventure downtown, the real monster is not Monk but the foolish townspeople all too eager to

The Warner Archive Collection DVD-R of Face of Fire is a good if not exemplary widescreen scan of this long unseen Allied Artists release. The image is a little soft in some sections and sharper in others, with stronger contrasts. It looks like a one-pass transfer, as a broken frame and some splices are allowed to jump. The widescreen framing trims a lot of heads, indicating the scan might have been planned to 'hang' from a line somewhat higher in the frame. But that's not a critical factor. Eric Nordgren's music score is clearly represented on the soundtrack. The composer did music for many Ingmar Bergman movies, but not many of these cues add a great deal to the picture -- except the over-emphatic dramatic sting at the conclusion, which works very well. Cameraman-art director Edward Vorkapich is often mistaken for Slavko Vorkapich, the montage genius and film theorist. Because Edward is also responsible for the nightmarish hallucination scenes in Albert Band and Louis Garfinkle's I Bury the Living, he is often confused with the other artist. 1

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Face of Fire DVD-R rates:

Footnotes:

1. By 'often' I really mean that I ignorantly conflated the two artists, for at least 30 years, until I lost a bet over the matter with Allan Peach. Not my most Savant-ish moment.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||