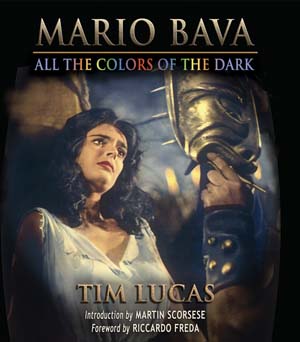

The old maxim "A job worth doing is a job worth doing well" must have been on Tim Lucas's mind while he was researching and writing his massive new biography,

Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark. The 51-year-old editor/publisher of

Video Watchdog and prolific DVD audio commentator and essayist began work on his self-published

magnum opus -- about the director of

Black Sunday,

Danger: Diabolik, and

Lisa and the Devil, among many other fine and hugely influential films -- some 32 years ago, taking pre-orders for it in December 2000 (in

Video Watchdog #66) and first announced it for publication in 2001. However, Lucas's obsession with completeness plus unforeseen production and logistical problems kept pushing back the book's release date; after several years of delays some customers were beginning to wonder if

All the Colors would

ever come out of the dark and see the light of day. "We weren't being insincere," Lucas says today. "We simply didn't realize the scale of the work that still lay ahead of us."

Well, that day finally came this past August when the first mountain of books arrived at Lucas's Cincinnati home -- from a printer on the other side of the world, in Hong Kong. Its stats are monumental, even by coffee table book standards: it's like a good-sized bowling ball, weighing in at 12 lbs. (5.45kg), runs 1,128 pages of four-column type crammed with nearly 800,000 words and what seems like at least a thousand beautiful full-color photos and ad art, all on heavy paper stock. The copy referenced for this interview was shipped to Japan via my parents' home in Michigan. My nearly 70-year-old mother complained that she couldn't get to some papers she needed because they were under the Bava book and, at her age, she couldn't lift it.

The book is undeniably pricey, currently $260 within the United States (including priority shipping). That's a lot of money even if you're a hard-core Bava fan.

Could any movie book possibly be worth such an investment? In a word: yes. Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark is a staggering achievement. Even after reading Lucas's many articles on Bava in the pages of Video Watchdog, even after seeing page samples of the book on his website, reading blog updates on its progress, and the hugely favorable reaction it was finally getting from Bava's family and professional associates I still wasn't prepared for what turned up at my doorstep one crisp October morning. Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark is not just the definitive work on its subject, it may be the most detailed, probing, and complete examination of any single filmmaker, anywhere in the world, ever.

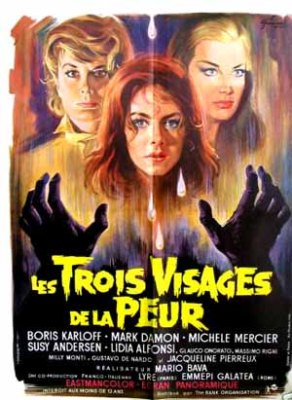

Consider just the chapter devoted to Bava's marvellous Black Sabbath: it runs 32 one-foot-square pages and, like all of Bava's other films, offers an intensely researched production history, complete production and distribution credits, a detailed synopsis, a lengthy comparison of dialog and other differences between the Italian and English versions of the picture, extremely well-written cast and crew biographies, an exhaustive account of the film's release throughout the world and its reception by contemporary reviewers, as well as Lucas's own observant critical analysis, behind-the-scenes and publicity stills and poster art from the U.S. and various European countries (with the poster artist usually identified), 34 illustrations in all. All of this material is beautifully integrated in such an entertaining, engrossing way that it never feels lumped together.

This is in no way a book limited to horror fans. Bava (1914-1980) worked in every conceivable genre and at every budget level the postwar Italian film industry had to offer: Spaghetti Westerns, giallo, erotic cinema, peplum, slapstick comedy, science fiction. A major selling point of the book is that a biography of Bava's career is almost by necessity an industrial history of postwar Italian cinema (and by extension, Italian cinema going back to the early silent days with its extensive coverage of the life and career of Mario's cameraman/sculptor father, Eugenio), and this facet of the book -- a portrait of the peaks and valleys of one country's film industry as experienced by one of its most diverse (if unrecognized) talents -- turns out to be perhaps its greatest accomplishment. Absolutely nothing about Bava's career is shortchanged.

And if you're still not sold on Bava's significance, consider Lucas's quote about Bava from actor Cameron Mitchell:

I did the first film of my life with John Ford, the man considered by many to be America's finest director, and it was an emotional experience I'll never forget....I had the pleasure to work with Orson Welles, and I also knew Fellini and Bergman quite well....[Bergman] reminded me of Elia Kazan, whom I'd worked for in A Streetcar Named Desire and Man on a Tightrope. Roaul Walsh, Sam Fuller...I mention the names of these men because I honestly feel that Mario Bava was perhaps the best and most underrated filmmaker of them all.

No director was more the visual stylist than Mario Bava, and the book's gorgeously reproduced illustrations, including original storyboards by Bava himself, are as integral to the book as its text. Appendices include a chronology of Mario's mentor-father, Eugenio Bava, a detailed Mario Bava filmography (no small feat considering the number of films he worked on without credit), a worldwide videography detailing the myriad versions and specs of Bava on home video; a discography; and, in a nod to those who waited patiently for so long, a long list of "patrons," an appreciation to folks who ordered All the Colors of the Dark all those years ago.

Through the Internet ether Lucas and I discussed All the Colors of the Dark, Bava, DVDs and audio commentaries (including The Mario Bava Collection, Volume 2, due out October 23rd), and the future of home video:

DVD Talk: What were the circumstances surrounding your first Bava movie-going experience? Were you hooked immediately?

Lucas: I didn't see a Bava film in a theater until 1977 (his last, Shock), and that was a shoebox-sized screening room. I didn't see any of his classics properly projected in 35mm until 1993, when I attended the first U.S. Bava retrospective in San Francisco and it was a big emotional experience. By then, I already knew the films well, but they revealed more of their impact in that setting; it's there that I got the idea for the subtitle All the Colors of the Dark. But I'm fairly certain that I saw both Black Sunday and Black Sabbath on commercial television before I was actually hooked. The movie that hooked me was Kill, Baby...Kill!, which I also saw on local television -- I knew to tune in from a review in Castle of Frankenstein (written by Joe Dante), which accorded it a "special recommendation" star. I found that movie astonishing because, a couple of weeks earlier, I had seen Fellini's Toby Dammit, which shared with the Bava film the diabolic character of the blonde-haired, little girl ghost with the bouncing ball. It was such a bizarre, inverted image of evil -- like nothing else I'd ever seen in a horror film -- and it had appeared before me not once, but twice. I could find no answers to my questions in the books about Fellini, so I moved on to Bava... and never stopped, because not much of anything had been written. I had to find out for myself.

DVD Talk: When you were a child, your widowed mother took you to the drive-ins on weekends. What are your strongest memories of that time?

Lucas: Changing from my street clothes into my pajamas in the backseat of the car and reading comic books until it was dark enough for the movie to start. The posters displayed in the concession stand area. Seeing movies like Pit and the Pendulum and King Kong vs. Godzilla under the stars. Crying when my mother didn't want to stay to see the third film on the triple bill. And sometimes falling asleep and feeling myself being carried out of the car and put to bed. She was a working mother with a night job and I saw her only on weekends, so the movies also represented our only time together when I was between the ages of three and eight, so the drive-ins were like my real home, away from the foster homes where I spent the days and nights of each week.

DVD Talk: What early movie books and biographies inspired you?

Lucas: The first three I ever bought were Hitchcock/Truffaut, Ivan Butler's Horror in the Cinema, and John Baxter's Science Fiction in the Cinema -- I read them all ragged. They all helped me to be more cognizant of which titles I circled to watch in each week's TV Guide, but I can't say any of them inspired me. My inspirations, so to speak, were Castle of Frankenstein magazine and, later, Cinefantasitique -- which I ended up writing for, for 11 or so years.

DVD Talk: What are your interests and preferences in so-called "serious" Italian cinema contemporaneous with Bava?

Lucas: I love Antonioni, though I've only been able to finally see some of his best work within the past several years, and also quite a few films by Fellini, Bertolucci, De Sica, and of course Leone. Once Upon a Time in the West, when I caught it unexpectedly as a co-feature at a local indoor theater, ripped my shirt open and ravished me; I've always felt that I entered that theater an unsuspecting child and left it as a man. With the exception of Deep Red and parts of the Three Mothers films, I find Argento overrated. While researching Bava's early career as a cinematographer, I developed an immense love and respect for the films of Aldo Fabrizi, which desperately need to be made available in English.

DVD Talk: Why have Italian genre films, several of which Bava pioneered, been ignored for so many years in critical circles?

Lucas: I presume the blame can be laid at the doorstep of bad dubbing, exploitative titles, and also the desire for critics in those years to be taken very seriously. My primary goal in founding Video Watchdog, as I outlined in my first editorial, was to treat these films with the critical respect they deserved and had so long been denied; I think critics are far more open-minded today, as a result -- and, of course, many of our most popular filmmakers of the last two generations now admit to being fans of Bava's work, so critics have to come around because the cinema itself has come around. Yesterday's B pictures are today's blockbusters, give or take a hundred million.

DVD Talk: Is Mario Bava a great auteur or "merely" a great artisan second-to-none?

Lucas: "Artisan" really is the correct word; he would have denied being an "artist." But, to the extent that his work represents and expresses its creator, I feel he was also an artist, if an unconscious one. I believe it's important to know something about any artist in order to fully appreciate their work, and until now, this has always been impossible with Bava, who always avoided the spotlight, but now my book can help to underline what was most personally expressive in his work.

DVD Talk: What was the critical reception to Bava's films in Italy when he was alive? How is he regarded there today?

Lucas: Bava's greatest Italian boxoffice success as a director was the movie known here as his greatest flop, Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs. Italy, being a very sunny place, is dispositionally opposed to horror as a genre, or was until cultural things like the goth movement and heavy metal made inroads there -- so horror films, especially Italian ones, were never appreciated there. To answer your second question, William Friedkin visited Rome last year and told an interviewer that his favorite Italian directors were Mario Bava and Dario Argento; the newspaper misspelled Bava's name.

DVD Talk: Were you able to see much of his father Eugenio's work?

Lucas: Not nearly enough to please me, but probably enough for the purposes of this book.

DVD Talk: Mario Bava spent a good chunk of his career, even after the international success of Black Sunday, salvaging other directors' pictures, usually without credit. Was this a mistake? Should he have been concentrating more on his own career?

Lucas: You could ask the same question about me: Why did I spend so many years publishing Video Watchdog and writing this book about Bava when it was my dream to write novels? Shouldn't I have been concentrating more on my career? Bava's situation, and mine so far, reminds me of that great line from Quatermass and the Pit: "I never had a career -- only work." I believe it was work that was most important to Mario; not just because it paid, but because his mind was especially attracted to solving new problems for the cinema. The Prologue I wrote for the book details a primal story from Bava's childhood that taught him not to think of himself as being special and impressed upon him the value of doing selfless work as a dedicated artisan. (This is quite the opposite of what all children are taught today -- "You're special!" -- and it may be a mistake to impress young minds with ideas like this.) Bava did have a certain amount of ego because he refused to be credited with this side work, as he knew his industry saw him as a director, and he didn't want to jeopardize that perception of him, which he knew to be rare and coveted and lucrative. But it was his greatest joy to be a cameraman and special effects artist, and he didn't want to surrender that life, either. So, when he wasn't working as a director, he worked anonymously at what he loved to do.

DVD Talk: Were you in touch with Bava prior to his death?

Lucas: I wrote him a letter outlining my intentions of writing a book in the late 1970s; I didn't keep a copy, unfortunately. I never heard back from him. I wrote him again, again nothing. When I was informed of his death, I sent a letter of sympathy to his son Lamberto, using the same address, and I did receive a reply some weeks later. In that letter, Lamberto told me that he found my letters in a drawer of his father's desk, where he kept "his important papers." I told Lamberto this was the finest memory he could give me of his father, and Lamberto signed on to assist me in my work however he could. He sent me rare photos and papers, as well as Mario's storyboards -- he didn't know that decades would pass before he saw them again. (But neither did I.)

DVD Talk: Your book has taken 32 years to complete. Was there some concern that you might have become lost in your subject, that you might be forsaking reader accessibility in the name of exhaustive completeness and minutiae?

Lucas: I began researching the book 32 years ago, but most of the writing I did prior to, say, 1995 was thrown out as unusable. Most of the book as it stands was written between 1997 and 2007. I can seriously say that I didn't give any factor more consideration than the level of my own curiosity. If my experience with Video Watchdog has taught me anything, it's that I know there are people out there who are just as compulsive and obsessive about these things as I am, if not moreso in some cases. I never fooled myself into thinking that this would be a best-seller or any kind of mainstream project, and I would rather write down and offer every pertinent fact than insult the time I'd invested with a very bland reduction.

DVD Talk: Why did it take so long?

Lucas: More to the point, "What worked against the book being completed faster?" In no particular order: Not speaking Italian... not having a publisher and so not having any particular deadline for all those early years... not being able to find key films... resolving to cover Bava's entire career rather than just his horror films (which meant tracking down tapes of dozens of films never seen in America or translated -- and awaiting the invention of the multi-standard VCR)... my work introducing me to more people who had access to more interviewees and more information... and the considerable distraction of having to produce the book between issues of a monthly magazine. The book is the length of ten normal sized books, in terms of word count, so I'd say the steady decade that was applied to its writing was well-spent.

DVD Talk: What were the hardest films to track down and see in their original versions?

Lucas: The films that Bava photographed. Of the ones he directed, the hardest to obtain was The Road to Fort Alamo -- at least after Rabid Dogs was finally released.

DVD Talk: What made you decide to publish the book yourself?

Lucas: Principally, it's the only way the project could begin to become profitable -- if anything requiring 32 years of research can ever be said to become profitable. The only other publisher ever to show an interest was McFarland and Company, but they expressed their interest after we had begun accepting pre-orders for the book, so we couldn't accept -- and I can't imagine making more than a few thousand dollars with them, and they would have wanted a much shorter book and insisted on doing it all in B&W. Better to do it ourselves and do it right.

DVD Talk: ...And McFarland probably would've wanted to call it "Mario Bava's 59 Movies."

Lucas: Or "All the Colors of the Dark: The Mario Bava Filmography, 1939-1980." No, we'd put too much into the book to give it away. Once I completed the manuscript, so to speak (because I continued adding to it), the actual creation of the book involved another three to four years, with six months alone spent on compiling the Index. It was a hell of a lot of work, with everything was done by Donna and me, except for some additional digital work and restoration done by some artist friends. The whole thing was hell on our marriage, frankly, and I wouldn't want to go through anything that demanding again.

DVD Talk: So, ultimately, was publishing it yourself worth the time and expense, or do you have some regrets not going with a sympathetic mainstream publisher?

Lucas: It was absolutely worth all the time and expense, though we could both have forgone the emotional toll.

DVD Talk: How's your Italian? Over the past three decades, did you take formal lessons?

Lucas: Never, because I didn't know I'd be still working on the same topic all this time. I can read and mentally translate the titles on Italian movie posters, but I don't have the knowledge to extend phrases into sentences or coherent speech. My pronunciation has improved a bit over the years, as I think my audio commentaries (recorded between 2000 and 2007) bear out.

DVD Talk: Is there anything in Italy comparable to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences' Margaret Herrick Library? Did you spend a lot of time in Italian archives, or did most of your production data come from other sources?

Lucas: The Turin Film Museum, I'm told, is the biggest cinematheque in the world, and I understand that Lamberto Bava intends to give Mario's papers and drawings and storyboards to them for safekeeping. As for spending time in Italian archives... I wish. No, I never went to Italy, just as Bava never came to America. I used the telephone, the Internet, the local library, and my own two eyes, basically.

DVD Talk: Who among those you wanted to interview proved to be the most elusive?

Lucas: I would have liked very much to interview Gina Lollobrigida, but she didn't answer my letters. Leticia Roman, the star of The Girl Who Knew Too Much, was very hard to find -- and once I did find her, she didn't answer my e-mail.

DVD Talk: Did anyone turn you down flat?

Lucas: Gianna Maria Canale, the star of I Vampiri and the significant other of Riccardo Freda. I found an address for her in Paris, and she responded to my letter, but she explained she didn't look back on her life, only forward.

DVD Talk: What was it like for an American actor to work on a Bava picture? Did they find working conditions difficult to adjust to after Hollywood? Working in multiple languages? Many of the Hollywood actors ended up making a lot of pictures in Europe. How did working with Bava compare with other Euro-productions?

Lucas: Some of the actors felt too isolated or insulated with Bava because he didn't give them enough, or any, direction. Basically, if he liked what an actor was doing, he left them alone. Other actors responded to his working methods wonderfully well. I can't say that the European actors responded better, because Cameron Mitchell loved him, too. Bava paid most of his attention to the technical side of things, but all of that was addressed to the mission of creating an atmosphere on the set that would help to conjure the right performances. Some actors, like Daliah Lavi and Elke Sommer, understood this very well, while others were left a bit perplexed.

DVD Talk: Most of these American actors today speak very highly of Bava. Were there exceptions? Was there a common thread to their admiration?

The only actor who had anything bad to say about Bava was Vincent Price, who had the misfortune to do the wrong picture with him -- a picture that no one involved seemed interested in making. Here, that movie (Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs) is considered a disaster, but in Italy, the Italian version became Bava's biggest boxoffice success of all.

DVD Talk: Of the people you interviewed, who among those who passed away before the book was published would you most have liked to have had a chance to see it?

Lucas: Harriet White Medin, who became a very good personal friend after our first interview. When I came to Los Angeles, she would drive me around, cook me dinner, take me to the airport. The last time I saw her, she drove me to the airport and there was a delay and we spent an hour or so in the restaurant there and she told me some amazing personal stories. I remember she was wearing a crisp blouse and stone-washed jeans, this woman who had played the starchy matronly housekeepers in The Whip and the Body and Blood and Black Lace. She was very girlish, even in her 70s. But she really didn't care for the Bava movies because of their violence, and pined for another giornalista to discover her and demand her answers to questions about Rossellini and De Sica. I asked her about them, too, but she knew I wasn't preparing a book about them. I don't think the material would have interested her overly much, frankly, but she would have shared in my happiness about finishing the book, and we could have shared a bottle of her beloved Valpolicella over its publication.

I was terrified for years that Lamberto Bava might die prematurely before the book was finished, so it was my great dream come true when he sent me a letter praising the book along with a photo of himself holding it like a new baby, surrounded by the beaming faces of his proud family.

DVD Talk: What facet of the book are you most proud of?

Lucas: The fact that Donna and I created it ourselves, independently, with the help of a large number of Bava fans who, like us, willed it to exist.

DVD Talk: In what ways did these Bava fans contribute?

Lucas: By pre-ordering the book, mostly. Others, knowing that the book was in progress, contacted me with offers to put me in touch with actors and other colleagues of Bava whom they knew. One of Bava's most elusive actors, Stephen Forsyth (the star of Hatchet for the Honeymoon), saw the ad in VW and phoned me out of the blue -- what a surprise that was!

DVD Talk: Are there any plans to distribute the book beyond the website and Video Watchdog? Will it become available through Amazon? Will it ever be part of a massive Bava boxed set?

Lucas: Amazon demands a large chunk of the cover price simply to carry it, so we're resisting them. Bookstores can order it from us, like they order books from any other publisher, and several already have. But no one will be able to offer it cheaper than we're offering it, so why not cut out the middlemen?

DVD Talk: Will there ever be a mammoth Bava boxed DVD set with your book, something along the lines of that massive John Ford set coming from Fox?

Lucas: An Italian DVD company approached us because they were preparing a deluxe edition of I Tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath) and wanted to license my chapter on the film to include as a limited softcover edition in a slipcase, but they dropped communications, so I presume something fell through in terms of the licensing or budget. Otherwise, there's nothing else like that in the works at present.

DVD Talk: Will the Italian versions of Caltiki, the Immortal Monster and The Giant of Marathon ever get an official Region 1 release?

Lucas: I don't know about Giant, but I am aware that Caltiki is available for Region 1 licensing. I heard through the grapevine that one leading company turned the movie down because it's in black-and-white.

DVD Talk: New York Times critic David Kehr paid you a great compliment on his blog when he said you virtually invented critical video reviewing, referring to you and Video Watchdog's ground-breaking obsession with transfer issues, multiple alternate versions, etc.

Lucas: I'm grateful to Mr. Kehr for saying that because it's true and it doesn't look so good when you make these claims for yourself. This once-alternative approach to reviewing is something I came up with while writing for a magazine called Video Times circa 1984; I can remember complaining to its editor that video reviews should be more than just dated movie reviews, because I was seeing how terrible many epics like El Cid looked as pan & scanned releases. So I forced their coverage in that direction, and I started Video Watchdog there as a monthly column of consumer-oriented observations.

DVD Talk: In sharp contrast, today the Internet is positively choking with DVD review sites. Is this a good thing? What irks you most about some online reviewers? Whose work do you enjoy reading?

Lucas: I'm not happy about the situation with Internet DVD review sites. Don't get me wrong, the quality of the criticism available online can be very good, but it has become a cancer in terms of print journalism and what was once proudly called "the power of the press." Internet critics have no power; newspapers and magazines do, but advertisers are fleeing them and they are now going out of business left and right. What online reviews have in their favor is immediacy, and this immediacy -- which means nothing in retrospective terms -- has made the work of amateurs more important to the DVD industry than the work of critics and reporters with decades of experience and, more importantly, the responsibility to report the truth. In the last couple of years, some of the biggest newspapers in the country have let their critics go. So the success of the Internet has already exacted a pretty high price in terms of what we've voluntarily given up in exchange for this ultimately meaningless immediacy. So the profession of writing and our tradition of reportage is being innocently undermined by the hobbyists online who are really doing it for no nobler reason than to score free screener discs. Unfortunately, we live in a world where the bad ideas -- better yet, let's say the eventual bad ideas -- cannot be retracted for the common good; they're just added to the pile with all the others, like the idea that it should be legal for people to drive while gabbing on their cellphones. Strangely enough, we've found that a sizeable number of Video Watchdog's readers are still not on the Internet... and if that's true of a small niche publication like ours, it must be truer of magazines with bigger circulations. But we don't accept advertising as they do, so the bigger magazines are being made to panic faster by the exodus of their advertisers to the Internet.

DVD Talk: Really? I find it very surprising that people who would fuss over the technical particulars of a DVD wouldn't have Internet access, or at least not take advantage of it.

Lucas: I suspect a lot of people simply can't find time for it in their lives, or perhaps they only think of it as a fancy way to play games or send mail. I must say, living without the Internet often seems to me a more sensible way to live, at least for compulsive people like myself who find it hard to log off.

Everything on the Internet could suddenly disappear overnight, while the legacy of print from centuries past survives in libraries and personal collections. Again, I'm not saying the quality of the criticism online is bad -- some of it is excellent -- but that excellent work deserves to be in print, and supported by an informed public, which is rapidly becoming another figment of our nostalgia. You asked me earlier about what criticism I read... There are a few blogs and message boards that I keep up with, but generally, I try to avoid reading criticism -- I get enough of it by writing it myself, and by publishing a monthly magazine of criticism.

DVD Talk: A leading question perhaps, but.... Have people become so obsessed with collecting, transfer issues, and how DVDs play on their hardware that there exists the danger that movie buffs are losing sight of the movies themselves?

Lucas: No, I think this shows that some people are looking more intently at movies than ever before. The important thing is to know that one is buying on disc the complete experience of a movie, so a matter of missing seconds can be infuriating.

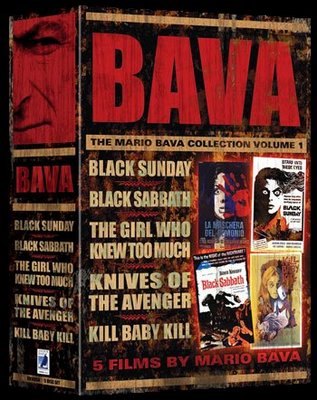

DVD Talk: I have almost all the Bava releases from six, seven years ago. What's the incentive to double-dip?

Lucas: Improvements in digital technology over the past seven years have been major. Some of the reissues are anamorphically enhanced for the first time, and some titles were imperfect the last time around -- like Twitch of the Death Nerve's noisy soundtrack, which is now corrected or at least bettered on the new version, retitled Bay of Blood.

DVD Talk: The Italian labs have a reputation for being notoriously difficult when it comes to accessing original film elements. Were there any problems with the Bava titles?

Lucas: I wasn't involved in any of that, but the films in this set were all licensed from Alfredo Leone; I assume he turned his own print elements over to Post Logic Studios, who produced the discs for Anchor Bay.

DVD Talk: What's the story with Black Sabbath and the problems encountered with MGM, who claim certain ownership of rights, in particular the English-language, AIP version?

Lucas: I'm not a lawyer, but Alfredo Leone has proved in a court of law that he holds the U.S. rights to the movie. He feels this entitles him to the AIP version held by MGM, but MGM (as I understand it) disagrees because it is a unique and separate version of the film -- with a different score, stories in a different order, different title, etc.

DVD Talk: Why is the Italian-language version of Black Sunday unavailable on DVD? Wasn't it announced and withdrawn?

Lucas: It is available on DVD in Italy, from Ripley's. As for the domestic release, the version released here is the Italian version but the English-dubbed version of the director's cut. It's the rescored, reedited AIP version held by MGM that has never been released on DVD; it was released once as a double feature laserdisc with the AIP version of Black Sabbath.

DVD Talk: As the veteran of so many audio commentaries, what constitutes a good track? What are a couple of the best tracks you've heard?

Lucas: Dead air is anathema to a good commentary, as is lack of preparation. I want to slap anyone who signs on to do an audio commentary and lets the mic pick up their murmurs as they watch the movie for the first time in 20 years. I pre-script most of my commentaries, time permitting, because I like scene-specific commentaries; it's not unlike scoring a film, I would imagine. I remember the Paul Mantee/Vic Lundin commentary track done for Robinson Crusoe on Mars being especially good; it was first issued on laserdisc and just came back out on DVD. These guys were the stars of the movie and it was the only big break they both had, and it flopped; they didn't hold anything back, so the track is an admirably candid study of the Actor's Life. Bruce Eder, whom I regard as the father of audio commentary, always did outstanding work for Criterion. David Cronenberg and Steven Soderbergh always deliver strong commentaries -- Soderbergh's track for Catch-22 with Mike Nichols is a personal favorite.

DVD Talk: Boy, I sure agree with you about the Crusoe commentary and Bruce Eder. That raises a question: What's going to happen to all these commentaries, as has already happened with a number of commentaries on laserdisc, as rights and home video formats change. How can they be preserved?

Lucas: The people who recorded them retain the rights to them. Either they will be revived, or re-edited to suit the latest medium, and others will recede into the past.

DVD Talk: Where does your wife Donna's taste in movies run?

Lucas: She's not an ardent film fan. She says she likes movies "about relationships," and we both enjoy watching the various series of HBO and Showtime; we were obsessive Sopranos viewers. Movie-wise, even if something is on that interests her, she will sew or quilt while watching out of the corner of her eye. She hates dubbing because it puts her to sleep, as do animated films for the same reason, and she prefers movies to be in English -- it's hard to quilt and follow subtitles. Her favorite movies are The Wizard of Oz and the Monkees movie Head (mostly because The Monkees are in it, rather than because it's a weird and innovative picture).

DVD Talk: If you suddenly inherited a million bucks and could launch your own DVD label, what would your first three titles be?

Lucas: Is that how I'd have to spend my inheritance?

DVD Talk: Is DVD dead (or dying)?

Lucas: Possibly. People are running out of room to store their collections, and the market is hideously oversaturated while DVD sections in stores are shrinking down to New Releases and TV Boxed Set aisles. I do believe that HD will eventually become a broadcast-only entertainment level, because regular DVD is already excellent quality and certainly good enough for most people, who remember what a quantum leap it was over VHS. I can envision a time when DVD could disappear from stores completely and become a rental-only medium through outlets like Netflix.

DVD Talk: What's the future? Downloadable video-on-demand?

Lucas: I would like nothing better than a downloadable VOD source with a completely unprejudiced database to draw from, one that had in HD every movie I presently have in my personal collection, and trustworthy enough to encourage me to discard my collection. We collectors proceed in our fanaticism because we're still convinced, on some level, that if we let any of this stuff go, we'll never find it again. (Okay, so why do we keep buying Blade Runner?) I'm now middle-aged, and my wife delights in reminding me that my available time to revisit any of my thousands of titles is ever-diminishing, and made all the more unlikely by all the new titles coming through my mail slot every week. I do have enough here to keep me very busy for the rest of my life, some of which time I should be addressing to matters of travel and exercise...so yes, I think whatever can promise us that we can throw away our collections is the most likely next thing to own us.

DVD Talk: Aren't having collections and personal libraries that reflect our tastes part of the appeal? What's the fun of having a bunch of files on our harddrives?

Lucas: I may not be the best person to ask because my own tastes are growing broader with age. It's not that I'm becoming less discerning, but that I've become more open to varieties of film, more knowledgeable about a broader range of filmmakers. I have so many discs now, they're all in banker's boxes, so I don't derive the pleasure of seeing my favorite titles shelved on the wall, nor do I have the necessary time to keep my print-outs of what I have up to date. So being able to pull down from the ether whatever I want to see, when I want to see it, and have more living space available as a result of unburdening myself of my collections, seems desirable to me as futuristic innovations go.

DVD Talk: Will there be any walk-in video rental shops five years from now?

Lucas: Maybe, but probably no rental shops that would interest you or me. But it's getting harder to find even a movie theater showing something that interests me.

DVD Talk: Why do you think that is?

Lucas: In a word, remakes. I've always gone to the movies to derive new experience, so now I hardly go more than a couple times per year. I can wait for almost everything to come to home video, where I know the projection will be superior, the company will be nicer, and the floors won't be sticky.

DVD Talk: What are some of your (non-Bava) "desert island" movies? A few titles you'd want to take with you if you were stranded with a DVD player and could only take a handful of movies?

Lucas: [Godard's] Contempt, [Antonioni's] L'Eclisse, most everything by Kieslowski (especially the Irene Jacob movies), [Rohmer's] My Night at Maud's, [Ken Russell's] Women in Love -- I like movies "about relationships" too, and think there's nothing more interesting in films or literature or indeed life than the magical forces that bring two separate people together to form that third entity known as a couple.

DVD Talk: In the past 25 years the damndest movies and genres -- Hong Kong musicals, East German Westerns, Turkish horror movies, etc. -- have one way or another become available to Americans willing to seek them out. Are there any great, largely unexplored areas of film that excite you now?

Lucas: The great thing about DVD is that it gives us the past on an even keel with the present. So the past is now open to us in ways even more vivid than what's happening now, because it was fresher then and predicated more on entertainment and ideas than on money. I fell in love with the Karl May Westerns last year and wept as Winnetou (Pierre Brice) died. These and the German Edgar Wallace krimi-thrillers need to be better known here in America.

DVD Talk: They sure do! Those German DVDs look fantastic and the movies themselves are so much fun....

Lucas: Alfred Vohrer and Harald Reinl were far and away the best of the directors who worked on these two series, and their work deserves to be much better known abroad.

Two years ago, I thought Korea was the new epicenter of world cinema; last year, I thought it was Spain. This year I've been spending mostly in the past. Where are the DVDs of Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras? And I would like very much to see the rest of Georges Franju before I die, thank you very much.

DVD Talk: Do you feel that, in the end, you got to know Bava personally on some level? What sort of man was he off the set?

Lucas: Very much so, and I write about this in some detail in my Prologue. I believe that Bava helped to steer me through the book on some level, because occasionally an inner voice would nudge me in directions that would lead to important discoveries -- people who could tell me things not properly known, or I might have a question in mind, pick a non-Bava movie at random to watch for relaxation, and recognize his lighting in the movie and answer my question in one fell swoop....Off the set, Bava was very much a homebody -- he was a devoted reader of Russian literature and international science fiction, he knew the basics of classical music, he had a Basset hound that he loved, and a wife who drove him crazy but to whom he was completely devoted, and he was very much the genial center of his family. His grandchildren thought of him as younger than their own father, as a kind of second father.

DVD Talk: Can you see yourself spending even 10 years of your life on another filmmaker, actor, or genre book?

Lucas: Unfortunately, I can -- because publishing a monthly magazine, writing a blog and a monthly Sight & Sound column doesn't leave me a lot of time to write books. If I was wiser, I'd be using that time to write another novel or another screenplay, something that would at least offer the possibility of profits enough to retire on. I think I should do something, too, about starting to collect the best of my widely scattered past work as a critic, interviewer, essayist and blogger on film in book form. That will be my next massive work 30-odd years in development, though I think I'll divide it between different books so they'll be easier for people to read on the bus.

- Stuart Galbraith IV

Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's latest books, Japanese Cinema and The Toho Studios Story, are being published next spring by Taschen and Scarecrow Press, respectively. His audio commentary for Invasion of Astro Monster is now available.