| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Viva Pedro - The Almodovar Collection

Pedro Almodovar (b. 1949) first began finding an American audience for his films in the mid- to late-1980s, when Cinevista began releasing early efforts like Labyrinth of Passion (Laberinto de pasiones, 1982), Dark Habits (Entre tinieblas, 1983), and What Have I Done to Deserve This? (Que he hecho yo para merecer esto?!!, 1984) to the art house circuit. Almost simultaneously, Orion snapped up the U.S. rights to Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios , 1988) and it proved to be a blockbuster by art house standards; the $700,000 production grossed ten times that in the American market alone. Since then he's become the best-known Spanish filmmaker since Luis Bunuel and easily the most successful.

Almodovar's core audience is gay men and socially progressive straight women, and his films are frequently quite explicit (but never pornographic), even though, contrary to his public image, some films like Live Flesh focus on straight men or women. (The set is being advertised on Amazon with an "R" rating, but includes NC-17 versions of Law of Desire, Matador, and Bad Education.) The director, himself out of the closet - "Yes, I am a gay man, but I love breasts," he says - tends to make deeply personal, often autobiographical films which grapple not only with issues of sexuality - gay, straight, and everything in between - but also drug use and addiction, issues of faith and Catholicism, Spanish politics and history, including that county's last years under Franco.

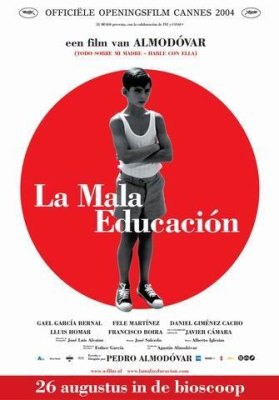

These facets of Almodovar's work, especially their frank, funny and adult sexual explicitness, will instantly turn off some. That's their loss. Americans tend to be prudish and puritanical about sexual matters, and Almodovar's in-your-face provocateuring is often shocking if simultaneously hilarious and insightful. But it's exactly that, Almodovar's ability to balance his screenplays about gays, transsexuals, drug addicts, etc., that are fundamentally honest yet not judgmental that makes his films so consistently entertaining and engrossing. Though most of his movies resemble postmodern re-workings of the kind of themes stylistic concerns that melodrama master Douglas Sirk applied to his movies back in the 1950s, they successfully dance a fine line between tragedy and high camp. In the otherwise quite serious Talk to Me, for instance, there's an outrageous, shocking, hilarious, and oddly touching fantasy sequence, suggested by The Incredible Shrinking Man, explicitly expressing a kind of ultimate form of love-making, with its shrunken man literally entering his lover's vagina to satisfy their sexual wants. Despite this Almodovar, to paraphrase Then again, Matador tested audiences with its shocking opening, with finds a man jerking off while watching on video a particularly violent murder from Mario Bava's Blood and Black Lace. The film is like a grave John Waters film en Espanol, following a celebrity bullfighter, Diego Montes (Nacho Martinez), who can't quite cope with the early retirement imposed upon him after he's gored in the ring. Unable to perpetuate his dark fix - the thrill of the kill - he takes to killing women after making love to them. He meets his match in attorney Maria (Assumpta Serna), who secretly is fascinated by him and consumed by similar passions. The film explores, often with great jet-black wit, the darker, primal side of human sexuality. If Waters' movies question and sometimes celebrate the boundaries of depravity, Almodovar, unlocks and acknowledges, sometimes through delirious excess, humankind's darkest, most taboo secrets. Audiences new to Almodovar might want to watch this film last, even though it comes first chronologically in this set. This and Law of Desire are probably his least accessible to mainstream moviegoers unprepared for such cinematic boldness. They'll also likely be surprised to find Antonio Banderas, then just 26, in a key role as Diego's hot-headed student. In Law of Desire (La Ley del deseo), Almodovar explores the complex sexual relationships of two siblings: Pablo (Eusebio Poncela), a promiscuous, coke-snorting gay filmmaker; and Tina (Carmen Maura), his onetime brother-turned-sister, a well-known transsexual actress. Stuck in a one-way relationship with Juan (Miguel Molina), who does not love him, Pablo begins an affair with Antonio (Antonio Banderas), who's initially uncertain about his bisexuality, but soon becomes obsessed with his new lover. Almodovar had cast Maura in lesser roles going back to 1983's Dark Habits (Entre tinieblas), but in Law of Desire he found his muse for that first big creative flowering, just as Banderas came to symbolize the iconic Almodovarian leading man. Both are excellent and utterly convincing, as is Poncela, whose understated, less flashy work is easy to undervalue. Law of Desire is essentially an old-fashioned Hollywood melodrama (complete with one character stricken with amnesia) but instead of Jane Wyman or Joan Crawford, its principals are gay men and a transsexual. With Tina's daughter (which Tina fathered while still a man) especially, the film also deconstructs familial conventions; Pablo and Tina may snort coke in back rooms and talk frankly about junkies in her presence, but Almodovar argues that Tina is a loving, basically responsible parent nonetheless. As the director says, "The characters in my films are assassins, rapists and so on, but I don't treat them as criminals, I talk about their humanity." Sort of like How to Marry a Millionaire gone berserk (a film later referenced in All About My Mother), or maybe like an insane asylum where all the patients believed they're Doris Day, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (original title: Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios) is Almodovar at his most visually stylish, from its wonderful '50s title design to its deliberately studio-bound sets. When married Ivan (Fernando Guillen) calls off his affair with voice-dubbing actress Pepa (Carman Maura), she not only goes off the deep end, but has to contend with Ivan's jealous, gun-toting wife (Julieta Serrano) and a visit from hapless Candela, in trouble with the law after falling for a Shiite terrorist. And so on. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown is the lightest and perhaps funniest film in the set, suggestive of pink cake frosting with candied sprinkles scattered on top. The picture is a riot of primary colors, and along with other Almodovar films from the period seems to have accelerated if not directly inspired the trend that quickly followed toward hip, retro furniture and fashions. Maura gives a wonderful, career-defining performance, and Banderas is back in a part that shows off a versatility rarely tapped once the actor moved to Hollywood. Jumping ahead seven years to Almodovar's next feature, The Flower of My Secret (La Flor de mi secreto), one can see a great maturation in the filmmaker's screenplays, which are more direct and uncluttered, with the occasional self-indulgence apparent in the films he made in-between giving way to more challenging themes with most of the fat trimmed away. Some might argue that Almodovar began repeating himself, with Bad Education especially similar to his earlier Law of Desire, but in reality the director is clearly pushing himself further in these more ambitious, later films, which exude a confidence without the sometimes pretentious need to impress. Instead, these pictures are consistently surprising in the way Almodovar structures his screenplays (thankfully, he seems never to have heard of Syd Field) which, despite their constant references to Sirk, All About Eve, film noir, "Moon River," A Streetcar Named Desire, Johnny Guitar, etc., keep the viewer off-balance. Talk to Her avoids structural cliches in its use of flashbacks, while All About My Mother establishes a point-of-view that Almodovar shakes up violently and unexpectedly. Live Flesh hinges on coincidences and irony familiar to fans of film noir but which, in this context, come off as surprising. And Bad Education offers a complex tapestry of stories and characters-within-stories, but perilously avoids the disastrous results (e.g., Passage to Marseille) that usually befall screenwriters trying to juggle so many balls in the air at once. In The Flower of My Secret, a lesser if well-made and beautifully acted Almodovar, Marisa Parades shines as a troubled, anonymous author of hugely popular, trashy romantic fiction (which she writes under a pseudonym) whose happy endings sharply contrast her unfulfilling marriage with a self-involved soldier (Imanol Aris) stationed in Serbia. In Live Flesh (Carne tremula), Victor (Liberto Rabal) the pushy, 20-year-old son of a prostitute (Penelope Cruz, featured in the funny, sweet prologue, where her character gives birth aboard a city bus) wants a "date" with junkie hooker Elena (Francesca Neri). They get into an argument in her apartment, which two police officers, David (Javier Bardem) and Sancho (Jose Sancho) misinterpret as an attempted rape. Sancho, already drunk and an abusive husband obsessed with his wife's apparent infidelity, is ready to gun down Victor on the spot. A struggle ensues, and David is shot and paralyzed from the waist down. Victor goes to prison, while in irony typical of Almodovar, David and Elena (now clean and sober) eventually marry, and he becomes a popular celebrity, the star player on a handicapped basketball team. Victor, who blames David for his misfortune, becomes consumed with jealously toward the apparently happy couple, and after a chance encounter begins stalking Elena while commencing an affair with an older, unhappy woman, Clara (Angela Molina). Live Flesh exemplifies Almodovar's fascination with the seemingly perverse lawlessness of fate and irony, in a film harkening back to classic film noir - only this, being an Almodovar movie, is shot in bright, primary colors. If Rabal lacks Antonio Banderas's charisma, the other performances are all quite good, especially Molina (of Bunuel's That Obscure Object of Desire), in tragic role that recalls Anne Bancroft's Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate. (Appropriately enough, Molina herself has recently played the part in a Spanish stage production.) All About My Mother ( Todo sobre mi madre ) is dedicated "To Bette Davis, Gena Rowlands, Romy Schneider...To all actresses who have played actresses, to all women who act, to men who act and become women, to all people who want to become mothers. To my mother" And indeed that's just what it is - a moving, remarkable tribute to mothers and actresses, to motherhood and gender, from Manuela (Cecilia Roth), who channels the once inconsolable grief she bears for her dead son, killed in an accident, to mothering of other sorts: from acting as the personal assistant to a middle-aged lesbian actress (Marisa Paredes), to caring for a pregnant, HIV-positive nun (Penelope Cruz, in an early, star-making role). Men are incidental in this Oscar-winning portrait (it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film) of the indomitable inner strength and sisterhood of these deeply troubled women, whom Almodovar declares are role-playing both literally and figuratively, as actresses on stage, and as symbolized by Manuela's friend Agrado, a sassy transsexual prostitute (Antonia San Juan) and Lola (Toni Canto), Agrado's transgendered ex-roommate who fathered both Manuela's and the nun's child. As Agrado puts it, "You are more authentic the more you resemble what you've dreamed of being." Talk to Her (Hable con ella), by contrast, is the study of two (more or less) straight men caring for utterly helpless women and thus, in one sense, grapple with innate or acquired maternalism. Macho Marco (Dario Grandinetti) is a travel writer whose bullfighter lover, Lydia (Rosario Flores), lays apparently brain dead in a coma after being gored in the ring. At the clinic where Lydia is cared for, Marco meets Benigno (Javier Camara), an effeminate male nurse hired by a wealthy psychiatrist to provide constant care for his comatose daughter, Alicia (Leonor Watling), a once promising ballet student. The two contrasting men form an unlikely friendship, with Marco drawn toward Benigno's dedication to his patient, his strange ability to carry on a relationship with her, and his refusal to lose hope that she might some day recover. The men turn out to be selfless and selfish, devoted and exploitative of their charge's helplessness. In its second-half the film turns on a shocking act of undeniable love that challenges viewers in ways as uncomfortable as it is unlike anything attempted in a narrative feature. That Almodovar clearly sympathizes with the character if not his actions epitomizes the director's boundless humanism. As always, the performances are just great. Grandinetti and Camara are superb, and Geraldine Chaplin, speaking fluent Spanish, has a nice supporting part and is well-cast as Alicia's ballet teacher. The set concludes with what arguably is Almodovar's best film to date and certainly his most personal and autobiographical, Bad Education (La Mala educacion), a project the director-screenwriter spent 10 years developing. In it acclaimed director Enrique (Fele Martinez) is reunited with Juan (Gael Garcia Bernal), who shows up at his office looking for work as an actor on Enrique's next film, bringing with him a semi-autobiographical story about their relationship - when the two were young boys at a Catholic school - that he hopes Enrique will adapt. In the story, 10-year-old Ignacio (Nacho Perez) is sexually abused by the school's principal, Father Manolo (Daniel Gimenez Cacho) and falls in love with fellow classmate Enrique (Alberto Ferreiro). Years later, Ignacio becomes Zahara, a drug-addicted transsexual who tries to blackmail the priest that had abused him. Juan wants to play Zahara in the film version Enrique agrees to produce, but the young director dismisses Juan's ambitions while longing to resume their long-lost love affair. Bad Education is a complex tale mixing noir elements (which include one genuinely shocking plot twist) with a kind of summation of all of Almodovar's favorite themes: gender, role-playing, Catholicism and Spanish life under and after Franco, homosexuality, the blurring reality and illusion, memory and longing, obsession and fulfillment. Just what Almodovar is trying to impress upon his audiences is difficult to say; as Roger Ebert writes, "The movie is not an attack on sexually abusive priests, nor does it have a statement to make about homosexuality, which for Almodovar is no more of a topic than heterosexuality is for Clint Eastwood." Video & Audio The eight films in the collection consist of reissues of older transfers, remastered editions, and a couple of titles new to Region 1 DVD. All look and sound excellent, and all are 16:9 enhanced. Matador, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and The Flower of My Secret are presented at 1.77:1, with Matador presumably shot for 1.66:1 projection and looking a bit tight in some of its compositions, though only slightly so. (As the oldest film its original film elements are in the roughest shape, but the film still looks stupendous compared with its original VHS release from 1986.) Law of Desire is presented in true 1.85:1, not reframed for 1.77:1 widescreen TVs, as thin black bars are visible at the top and bottom of the frame. The remaining films were all shot in Panavision, and Almodovar and his cinematographer use the 'scope frame extremely well; panning and scanning would ruin their careful compositions. Bad Education's story-within-the-story is framed for 1.85:1 while the rest of the picture is 'scope. The transfer opts for bringing in black bars on the sides, creating a windowboxing effect, rather than enlarge the image to fit widescreen TVs, and this is indeed the best way to have gone. Matador and Law of Desire are new to DVD, while Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and All About My Mother have been remastered. The Flower of My Secret, Live Flesh, Talk to Her and Bad Education are identical to earlier DVD releases from 2005, 2001, 2003, and 2005, respectively. Each film offers optional subtitles in English and French except for Bad Education (English subtitles only) and Live Flesh (which has Spanish subtitles, as well as English and French). Talk to Her also includes an alternate French audio track. Almodovar's movies abound with music and song, the lyrics of which are sometimes translated, sometimes not. The stereo mixes, from The Flower of My Secret onward, are excellent. Extra Features Supplements are plentiful if erratic and flawed. Matador, Law of Desire, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), and All About My Mother (1999) are bare bones, while the other films have extras carried over from their original releases. The Flower of My Secret includes a 20-minute Making Of documentary in 4:3 format, along with trailers (none are enhanced) for that film, All About My Mother, and Talk to Her. Live Flesh includes only a trailer, also 4:3 letterboxed, while Talk to Her offers an audio commentary by Almodovar who's joined by Geraldine Chaplin. Both speak Spanish and the commentary is supported by yellow English subtitles. Bad Education offers the most in the way of extras, with an audio commentary by Almodovar (solo this time, again in Spanish), four-and-a-half minutes of (two) deleted scenes in 16:9 format, a photo gallery of myriad artwork, and two featurettes. The first of these, Red Carpet Footage from [the] AFI Film Festival is quite good, mixing scenes from the film with interviews with Almodovar and cast members at a screening at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood. A Making of 'Bad Education' is rather absurd; it's nothing more than a montage of behind-the-scenes footage running less than two minutes. The boxed set's ninth disc consists of three sometimes redundant featurettes made by the same company in the same style with the same interview subjects. Deconstructing Almodovar runs 52 minutes and picks apart the creative process, supplemented with film clips and interviews with an impressive number of collaborators (including Cruz and Maura); Directed by Almodovar (27 minutes) talks mainly to actors about their experiences working for the filmmaker, while Viva Pedro (25 minutes) is more biographical, told mainly by his brother-regular producer Agustin. Also included is an eight-minute preview of Almodovar's latest, Volver, and a 16:9 trailer for that film. Unfortunately, though the documentaries are all letterboxed, none are enhanced and subtitled in such a way viewers with widescreen TVs will be forced to watch them 4:3, resulting in some pretty tiny film clips. Finally, the postcards are quite nice, with attractive reproductions of each film's original artwork. Parting Thoughts For movie lovers, Pedro Almodovar has become as much a treasure as the classic Hollywood movies he so constantly references, and each new "Un Film de Almodovar," the credit Almodovar precedes each movie with, has become a kind of beloved trademark, like Hitchcock's cameos or Saul Bass's title designs. Those who have avoided or simply never got around to picking up these titles before now can get them all at once, a full-blown retrospective in a box. A DVD Talk Collectors Series title. Film historian Stuart Galbraith IV's most recent essays appear in Criterion's new three-disc Seven Samurai DVD and BCI Eclipse's The Quiet Duel.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||