| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Executioner's Song: Director's Cut, The

On July 19, 1976, Gary Gilmore, a 36-year-old ex-con with a long, long history of violence and anti-social behavior, senselessly robbed and then murdered, in cold blood, gas station attendant Max Jensen, in Orem, Utah. The very next night, Gilmore, recently separated from his 20-year-old girlfriend, Nicole Baker, robbed and murdered motel manager Bennie Bushnell in Provo, Utah. Gilmore was almost immediately fingered by relatives and witnesses as the culprit and was tried for the Bushnell murder, for which he was convicted and sentenced to death. But contrary to most convicts who find themselves on death row, Gilmore set himself apart - and became a national figure - by demanding that his lawyers cease all appeal processes and that the state of Utah carry out his sentence: death by firing squad. If carried out, Gilmore's sentence would be the first execution in the United States in over ten years, after endless court cases (including the Supreme Court declaring the death penalty unconstitutional) across the country had effectively squashed the death penalty as a viable form of state punishment. Separated from Nicole, the controlling Gilmore and the easily-duped Baker contrived to kill themselves in a botched suicide attempt. Both survived (although Nicole was then subsequently institutionalized due to the attempt and for drug addiction), with Gilmore more resolved than ever to die at the hands of the state. Ultimately, his wish - as well as, more importantly, the wishes of the state and people of Utah - was granted: Gilmore was fatally shot by firing squad on January 17, 1977.

The Gilmore killings and his subsequent execution were sensationalized front-page news for months prior to Gilmore's sentence being carried out, and it's easy to see how Lawrence Schiller, a former photojournalist and filmmaker who had already collaborated on Norman Mailer's notorious Marilyn biography, smelled a big, fat story suitable for a big-scale book (and presumably a suitably big, fat paycheck). With Schiller engaging Mailer to write the novel, some critics at the time were stymied as to why Mailer, long-considered one of America's literary giants (although his reputation was tailspinning prior to The Executioner's Song), would want to waste his time on tabloid trash like the Gilmore case. After all, murders like the Gilmore ones occurred every day in America; what made this one special? Obviously, the media frenzy over the resumption of the death penalty angle certainly helped, as did, perhaps more importantly, Mailer's identification with Gilmore's preoccupation with karma, reincarnation, his passionate, troubled relationship with women, and his explosive temper, rage and capacity for violence - all qualities that Mailer had both written about before, and had exhibited, to an extent, in his own personal and public life (most infamous among his many explosive moments, Mailer had almost fatally stabbed his wife in 1960). Two-and-a-half years later, Mailer delivered The Executioner's Song, a 2,000-plus page "true life novel" (a term I always thought Mailer came up with less to identify a new type of genre than to distinguish the novel from Capote's more accomplished In Cold Blood) that skyrocketed to the top of the sales charts and re-established Norman Mailer as one of America's most important literary figures. Since part of Schiller's tactic in securing the exclusive rights to the stories of many of the participants, during the preproduction and research of the novel, included payments for movie rights, a TV adaptation was probably always on the table (indeed, Schiller and Mailer initially thought the story might make a good Broadway musical). Mailer wrote the screenplay, and Schiller produced and directed, with the TV miniseries premiering over two nights on NBC, late in 1982.

Assessing the artistic pluses and minuses of The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut is difficult because footage is missing/added/restructured in this particular "Director's Cut" version. I had read about a European theatrical version that included more nudity and strong language, that ran around 135 minutes (the same running time as this DVD). And there are instances here of vulgar language that certainly didn't air on network TV in 1982 (indicating that these alternate takes were always intended for a theatrical release of some kind). As for nudity, there's a brief shot of Arquette from behind, bathed in shadow, that's not especially revealing, as well as a topless scene that has obviously been re-framed to avoid nudity. So I'm not even sure if this particular cut is indeed the much-talked about European version, of if that's been altered here, too (the back of the box, interestingly, says, "Never before seen" - which just might be true, with these changes). So discussing the film's lack of narrative focus and insufficient motivation and characterization becomes troubling when you're not really sure what version of the film you're actually watching.

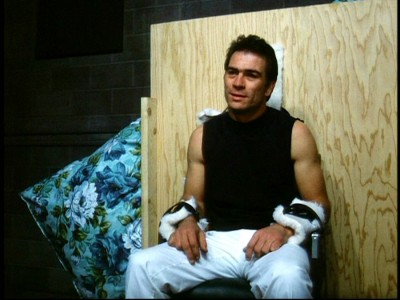

With that caveat established, what is presented here in The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut certainly doesn't rise to the literary achievement Mailer's aspired to (with many critics still debating whether or not Mailer succeeded there, either). What merits The Executioner's Song may have possessed were largely found in Mailer's sprawling, epic treatment of Gilmore's life and crimes, with Mailer departing from his usual stylistic gymnastics to provide a stripped down, "western" feel to his prose. There is a weight to The Executioner's Song that, regardless of the worth of Gilmore as its subject, is impressive. But whether or not Mailer really got at the "truth" of Gilmore (if such a thing is even possible) is another story, and some reviewers felt he achieved less than that, painting Gilmore into shades of himself, rather than what Gilmore truly (and frighteningly) was: a shiftless, blank cipher. As for the film adaptation, by eliminating the massive detail that Mailer incorporated into his narrative (which, to be fair, is necessary for most cinematic adaptations of literary work), Mailer in his screenplay has now forsaken "Gilmore the center of a literary epic" in favor of Gilmore, the subject of an elongated, but certainly not a particularly original, true crime miniseries. The accumulated weight of Mailer's details and the hard, flinty prose that made reading the book an aesthetic experience in and of itself, are now gone in the more literal, linear film version.

That's not to say, though, that The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut doesn't have worthwhile elements to it. First and foremost, Mailer and Schiller do play fair in countering most instances in the film where the viewer may be tempted to feel sorry for Gilmore (at least until the film's final act). According to this screenplay, Gilmore was given chance after chance to straighten out his life, with a fairly strong support system of relatives and friends who expended quite a bit of energy to help him, only to have the immature and dangerously unbalanced Gilmore throw that aid right back in their faces. And throughout the film, the screenplay is careful to offer a contrary view to some of Gilmore's more subtle manipulations (usually offered up by his shrewd cousin Brenda, played superbly by a young Christine Lahti). Up until the final execution scene, the screenplay and direction tends to favor a balanced approach to Gilmore's actions that I don't remember in the more aggrandizing novel (I've always wondered if Mailer subtly changed the focus of his script to put Gilmore in a more negative light after Mailer's shameful experience in 1981 of personally aiding the release of murderer/would-be author Jack Abbott...only to have the psychotic Abbott turn around and kill an innocent young artist some weeks later).

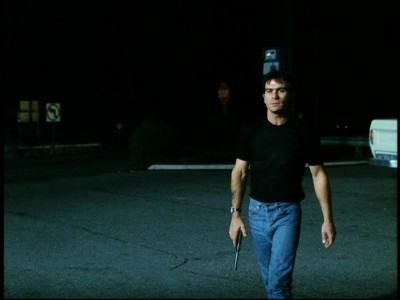

And Schiller is very good at getting across the rather hopeless, bleak, subterranean underworld of hardscrabble Utah. Schiller, with the expert aid of cinematographer Freddie Francis (The Innocents, Dune), perfectly captures the down-and-out bikers and low-lifes that Gilmore associates with after his release (Bryan Ryman's production design, with his realistically grungy sets, is letter-perfect). As well, Schiller at times has an admirably straight-forward, almost documentary feel to his scenes that, coupled with the excellent thesping by the talented cast, gives The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut a feeling akin to director Richard Brooks, In Cold Blood, probably the standard-bearer for this type of true-crime film. Schiller's design of Gilmore's first killing is quite chilling, with the director executing a scary dolly shot of Jones coming close to the camera as he makes the fateful decision to shoot somebody, anybody, to assuage his inexplicable rage. And quite correctly, Schiller shows the immediate, horrific effects of Gilmore's shooting of Bennie Bushnell, detailing to the viewer the terrible agony he and his wife (who held him while he died) went through during his death throes. Seeing Bushnell die in such a terrible way goes a long way towards eliminating any sympathy one might feel for Gilmore.

Ultimately, though, it's fairly clear where Mailer's and Schiller's sympathies lie as to Gilmore's final fate, which essentially undercuts the naturalistic balance that we had seen throughout the film. Tellingly, the opening shot of this particular cut of the film shows Gilmore playfully trying to figure out the airport's automatic doors; our first impression of Gilmore, therefore, is encouraged to be positive; to like him and to laugh with him. A depiction of his final "party" at the prison just prior to his execution is staged to humanize (and soften) the Gilmore character (with many shots of prison guards and visitors smiling and laughing and back-slapping Gilmore), while the final execution is staged to play up the so-called "injustice" of killing a killer. Schiller includes frequent shots of Gilmore's uncle Vern, played with great skill by Eli Wallach, looking agonized and shaking his head at the unfairness of his death, which are bookended around Vern's final words to Gilmore, which are steeped in playful bravado and sadness on Gilmore's part (including having Gilmore joyfully/ruefully asking Vern to pull him out of the chair, a deliberately selected and sympathetic tone that was in opposition to many witnesses who said Gilmore's laconic, unapologetic last words, "Let's do it," were more in keeping with his overall general mood).

Certainly it's not surprising that Mailer's and Schiller's film would ultimately come down on the side of Gilmore's execution being wrong (both were opponents of the death penalty, and both professed, particularly Schiller, a friendship with Gilmore). And while the film does try to be fair in exposing some of Gilmore's manipulations, the film is distant when it comes to the "true" tragedy of this story - and that's certainly not Gilmore or his choices in life. The real tragedy, as always in these kinds of cases, lies with the victims, who are essentially anonymous here in The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut - which again isn't much of a surprise (victims aren't as "interesting" as the criminals to "artists"). Sympathy and empathy, you would think, should lie squarely, unwaveringly with the victims, a proposal that always leaves would-be "edgy" artists and writers, attracted to those who truly flaunt the conventions of society (in ways the artist and writer would never dream of doing), and who therefore love to romanticize and humanize and sympathize with these murderers and animals, cold. But everyday people (the "squares" that those same artists and writers love to sneer at and mock) know all too well the reality of these dubious artistic "creations," like the Gary Gilmore of The Executioner's Song because they have to live with the consequences of those "misunderstood, damaged," and most importantly to the artists, "morally equivalent" criminals (ego-maniacal Mailer infamously stated he was willing to sacrifice portions of society to preserve Jack Abbott's talent -- in other words, it was okay for Abbott to murder innocent people as long as his talent was allowed to flourish).

In the end, this kind of literary and cinematic "invention" (and that indeed is what is presented here in The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut) is closer to romanticized fiction than "reality" - and far less honest than a typical Harlequin romance (speaking of "honesty," why does producer/director Lawrence Schiller give himself a different name for his own character in the film?). Because at his very core, Gilmore was nothing more than a cheap punk who killed innocent people out of unexplainable - and therefore, thoroughly prosaic and terrifying - rage and anger. Mailer himself admitted he probably didn't come close to explaining Gilmore's actions, let alone revealing Gilmore the man, and neither does The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut. At the very center of the film - the killings - is a hollow feeling because we realize, outside all of the clichés about prisoners unable to cope with society and karmic reincarnation and Nicole being sexually turned on by Gary's "demonic" presence, that the filmmakers (and therefore we viewers) will never know what made Gilmore tick, and why he killed those innocent people. Even more disturbing is Mailer's and Schiller's failure to come up with any compelling examination of why Gilmore wanted to die - the only distinction to his otherwise relatively "ordinary" crimes (if such heinous acts could be thus described). While Mailer made a big deal in his novel about Gilmore's karmic desire to save his soul by dying for his sins, all of that is dropped here in The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut, with Gilmore admitting to his brother in a jailhouse scene that he just wants to die because...he can't handle any more prison. What Mailer saw as the poetic, majestic, "good side" of Gilmore in his novel, has been supplanted with a thoroughly ordinary - and cowardly - reason for dying. Which one was the "real" Gilmore? The karmic traveler, atoning for his sins, or the cheapjack little punk, taking a dive because he couldn't handle the joint? You won't find out in The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut, because the film doesn't know itself (although most of us with a lick of common sense already know).

The DVD:

The Video:

The full-screen, 1.33:1 video transfer for The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut does have a fair amount of grain and dirt, although things start to look better as the film progresses. Overall, though, it's apparent that no restoration has been conducted from what looks to be a copy from a print, not the original elements. There are no compression issues, though, and all things considered, it looks better here than it did the last time I saw this on cable.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono track accurately reflects the original network broadcast presentation. All dialogue is clearly heard, and close-captions are available.

The Extras:

There are no extras for The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut.

Final Thoughts:

The term "Director's Cut," generally speaking, would seem to indicate the "definitive" version of a particular film. But those fans of The Executioner's Song should know that The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut is actually a shorter version of the longer U.S. miniseries (and it's also probably not the much-talked about foreign theatrical version). There are plenty of four-letter words now in the film, but no real nudity (and no explanation on the disc as to what version we're actually seeing), so it's anybody's guess (experts on the various cuts feel free to email me with info). As it stands, though, The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut is at best, a flawed experience. The most compelling elements of the story - who Gilmore was, why he killed, and why he wanted to die - aren't answered here. But we are left with some interesting turns by the excellent cast (Jones, Wallach and Lahti are standouts), and Schiller does have a clinical, hard-edged way with his scenes (even the romantic ones) that might catch your attention. Rating this edition is tough, because of inherent flaws in the film itself and in this particular DVD edition, but I'm going to recommend The Executioner's Song: Director's Cut anyway, because at least it's an interesting failure.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||