| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

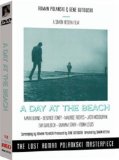

Day at the Beach (1970), A

Code Red has released Roman Polanski's "lost masterpiece" (as it states on the DVD front cover), A Day at the Beach, the 1970 adaptation of Heere Heeresma's 1962 novel about a day in the life of a spiraling-down alcoholic (which in turn was remade as Een Dagje Naar Het Strand in 1984 by slain Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh). Written by Polanski and directed by first-time director Simon Hesera, A Day at the Beach was apparently never released in the U.S., and subsequently "lost" by Paramount (some kind of legal glitch?), and has had only sporadic film festival showings since 1970. Intended as Polanski's directorial follow-up to his previous Paramount smash-hit, Rosemary's Baby, Polanski withdrew from the project after the murder of his wife, Sharon Tate, and their baby (it's been written that the film was subsequently suppressed by the studio out of respect for Polanski). These notoriety factors, along with the promise of seeing a cameo by Peter Sellers during the nadir of his film career, have kept A Day at the Beach a cult title that many film fans have heard about, but very few have seen.

Set near an unnamed British seaport (although the film looks like it was filmed in Denmark), A Day at the Beach follows alcoholic, failed intellectual Bernie's (Mark Burns) day trip with his "niece," Winnie (Beatie Edney, already a gifted actress here). Arriving in a miserable, drizzling rain, Bernie isn't exactly welcomed by either Winnie's mother, Melissa (Fiona Lewis), nor her husband, Carl. At times both insulting and threatening, he obsequiously bums money off Carl, so he can take Winnie out in a proper fashion...which really means money he'll use to buy alcohol. A look of absolute dread crosses Melissa's face when she sees Bernie, but Winnie, who appears to be around six-years-old, is delighted to see her beloved uncle. But this show of affection - as with any sign of anything civilized coming from anyone Bernie encounters - is met with selfish cruelty. Winnie, who wears a leg brace due to some unnamed handicap, is asked by Bernie if she doesn't have any trousers "to hide those irons." Winnie dutifully trots back to change, but Bernie hurries her into her yellow rain slicker and they're off for the day.

And what a miserable, wet, cold day it turns out to be for them. Constantly raining, the two grab a train for the seaside (but not before Bernie is smacked around by loan shark Louis, played by Bertel Lauring) where Bernie spends the entire day boozing it up every chance he gets, insulting the various tradesmen he encounters while scamming alcohol off them, and ignoring Winnie to the point where we often fear for her safety. A chance meeting with a "friend," Nicholas (Maurice Roeves), a former poet and now teacher, leads to more drinking with Nicholas and his wife, Tonie (Joanna Dunham), who responds sexually to Bernie's insulting behavior, and more neglect for Winnie, who's locked in a car with Nicholas' and Tonie' small son. Fueled by self-pitying rage and alcohol, the night spins further out of control for Bernie, despite the totally inadequate reassurances by small child Winnie that everything will be alright.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Contrary to popular assumptions around the ivy-covered halls of DVDTalk U., I don't constantly float six inches off the ground in candy-floss reveries where I'm discussing A-bomb shelters with my next-door neighbor Jack Webb (as he thumbnail-opens a pack of Chesterfields) while in the kitchen, Donna Reed makes us a four-layer chocolate cake. My cinematic interior life isn't solely comprised of nostalgic trips down 50s and 60s pop culture memory lanes. I do actually watch and enjoy (horror!) what some might label "art house" films. Which brings me to this relevant European art house film...from 39 years ago (sorry - couldn't resist). I would imagine that most serious film fans might seek out A Day at the Beach for Polanski's connection to it, having been slotted to direct his screenplay before the tragedy of the Manson murders forced him to abandon the project. Although fun to contemplate and discuss, ultimately, I don't see much point in discussing how A Day at the Beach might be different had Polanski directed it, because he didn't, obviously. The film is what it is. Would it have been "better" with Polanski at the helm? Possibly. Possibly not (I suspect it would have been funnier in spots, though - this version is unrelentingly mordant). His script is a tough sell, as it's presented here, but as most film fans know, a script in the hands of a director like Polanski - even if he wrote it - becomes something malleable in an overall visual and thematic aesthetic. Who knows what he would have changed once he turned the camera on? And frankly, who knows what director Simon Hesera changed or left out or enhanced when he picked up Polanski's script?

As filmed, A Day at the Beach is quite interesting (up until the end, where the director or screenwriter missteps) for presenting an on-screen drunk who remains largely unsympathetic and unromanticized during this awful day out with his daughter. While newer films like Leaving Las Vegas and Sideways, for all their efforts to appear multi-faceted in their depictions of alcoholics, still ultimately romanticize their characters (audiences were envious that a mess like Cage scored with a beauty like Shue, while Sideways fans organized trips that retraced the characters' wine country jaunt). Even Huston's Under the Volcano, which presented about as bleak a depiction of an alcoholic's life and its ending as one is likely to see in a film, still allowed us to mourn the promise that was Finney's character, making us believe that some essential good (even an elevated, cultured good) was inside the character, if only it could dry out long enough to emerge.

Not so with A Day at the Beach. Bernie (played with a bleary, scary perfection by Mark Burns) is a thoroughly reprehensible, pathetic figure who becomes worse the longer we get to know him. A failed, emotionally stunted intellectual who doesn't have enough money to take his daughter out for the day, he sneers at the people he cons out of money and booze (or perhaps more correctly, the people he bullies and frightens, since everyone is wise to his loquacious blarney), while he drinks himself to death as he wallows in impotent self-pity, all the while endangering the life of his child through his inexcusable, willful disregard for her feelings and her personal safety. In most films featuring this kind of cinematic drunk, we're allowed to enjoy the vicious, snarling ripostes and monologues that insult and cut down the other characters in the film (think how enjoyable it is in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? when Burton, after utterly humiliating Dennis and Segal, self-satisfiedly says, "And that's how you play, 'Get the Guests.'"). That only happens once in A Day at the Beach, when at the allowance of gay shopkeeper Peter Sellers (delicious, but a performance out of kilter with the rest of the film's mood), Bernie verbally destroys Seller's equally camp lover, Graham Stark. But even that moment is tempered by the knowledge, both by us and by Bernie, that he had to allow himself to be hit on by Sellers to get his free beer and a sea shell for Winnie.

Except for one or two moments where the vestiges of an actual caring father and human being surface from within the sodden Bernie (buying his child a sea shell; buying her a bowl of soup when she's gone all day without food), his behavior is repulsive. Upon entering Melissa's apartment, he steals the last of her milk (or was it Winnie's breakfast milk?), a copy of Playboy, as well as two big shots of vodka. And when he first sees the adorable, lovely Winnie, he disparages her appearance due to her leg brace. He uses her affliction as an excuse to fob off his loan shark, and later leaves her alone for long, long stretches of time - utterly oblivious to the physical and psychological harm that may come to her - as he pursues another drink. He doesn't even bother to stick with her in her bumper car ride, where she's unable to reach the pedal because of her brace (ultimately, he only comes to help because the ride operator is forcibly trying to remove Winnie from the car: Bernie's not helping Winnie, he's thumbing his nose at any and all "authority" figures).

Indeed, we don't feel sorry in the slightest for Bernie's impending doom; the film's true dread - and it's a thoroughly uncomfortable one - comes from the constant state of anxiety the viewer feels for the that poor child, left in the "care" of Bernie, an anxiety that almost becomes too much for the viewer by the end of the film. That yellow rain slicker of hers is aptly chosen: it's a persistent warning flag for the danger she faces. Often left alone outside pubs for hours at a time as Bernie gets hammered, pathetic Winnie gets caught in some fishing nets (she has to get herself out), is locked away in a car for hours with a small crying boy, and finally, is left alone in a dark corner of a building, at night, out in the elements, and told to count until Bernie gets back from "making a telephone call" (which means getting a drink). On the back of Code Red's DVD, they state that Winnie is Bernie's niece (she calls him "Uncle Bernie"), but it seems pretty clear by Bernie's initial reaction to Winnie that he's her father (once in Melissa's apartment, he buries his face and smells her still-warm side of the bed...would a brother do that?). His threat to tell Winnie who her "real" father is, is clearly meant to refer to himself (no doubt Melissa has passed off the shiftless Bernie - who could have been as inconsequential to her as a one-night stand - as Winnie's "uncle"), while his agonized apology to Winnie at the end of the film can only be that of a father to the daughter he has let down in every possible way. The fact that Winnie is Bernie's daughter only makes his treatment of her all that much more sordid and repellent.

Unfortunately for A Day at the Beach, director Hesera blows the ending by actually trying to make us feel sorry for Bernie. It's plausible enough for us to believe that Bernie might make such a groveling, hysterical apology to Winnie when he wakes up in a sand hole on the beach (with poor Winnie cowering in an enclosed beach chair far, far up the beach), with ever-loving Winnie smoothing his hair and promising him everything will be alright with "taxi and home." That scene doesn't engender sympathy for Bernie, but pity. But Hesera oversteps when in the previous sequence, he shows various townspeople reacting angrily to Bernie's nighttime abandonment of Winnie, left outside in the pitch dark. Hesera shoots these townspeople as grotesques, shot in ugly, unflattering light, letting their distorted yelling overlap incoherently. This is where A Day at the Beach shows what may truly be on its mind - that Bernie's existential isolation is at least grounded in an excusable reason: society is pedestrian and ugly - and where A Day at the Beach finally loses the audience's willingness to stay with the picture. There can be no excuse, no mitigating circumstances, for Bernie's behavior towards Winnie. To follow through and validate the facile, clichéd critiques of prosaic humdrums that unfortunately populate the world and make things difficult for "misunderstood" artists and thinkers like Bernie - critiques that had been popping up in the film whenever Bernie lashed out at his victims - is to miscalculate the degree to which Bernie's mistreatment of Winnie has already repulsed the viewer.

The DVD:

The Video:

Code Red has provided, considering the film's troubled history, a pretty strong looking anamorphically enhanced, 1.78:1 widescreen transfer of A Day at the Beach. Print damage is evident at times (mostly scratches and dirt), but infrequent. Colors are for the most part strong (master cinematographer Gilbert Taylor's framing is often striking), but there can be some softness and fuzziness in some of the longer shots. Grain is apparent, but I'd put that up to the film stock and the way these types of films looked back in '70.

The Audio:

The English 1.0 mono audio track has noticeable hiss, but overall, the sound is serviceable. All dialogue is distinguishable, but there are no subtitles or close-captions.

The Extras:

Only some trailers for Code Red releases are included here (no trailer for A Day at the Beach - if the studio had even cut one back then).

Final Thoughts:

For most of its running time, A Day at the Beach is a downbeat, admirably unromantic look at a sour, failed alcoholic intellectual, made harrowing by his mistreatment of his young daughter on their day trip to the beach. Only when the director (or the screenwriter) decides to make our anti-hero sympathetic does he misstep. Thoroughly unpleasant, but it stays with you. I recommend A Day at the Beach.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||