| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

L'Urlo (The Howl) - Uncensored Director's Cut

"Where are we?"

"Me, too."

Cult Epics has released L'Urlo (The Howl), director Tinto Brass' cult avant-garde, mondo weirdo-fest from 1968 starring the incomparably delectable Tina Aumont. A memorably bizarre mixture of surrealistic sex and violence and counter-culture rabble-rousing, L'Urlo isn't as impenetrable as one might fear, partly because Brass leaves it up to you as to what it all means. Logic and morality are thrown out, and sensation and emotion and feeling dominate. Cult Epic's print is supposedly restored to the director's original, uncensored version, while the addition of a commentary by Brass himself adds immeasurably to the fun...well, maybe not "fun."

There is a plot to L'Urlo, but it's just a loosely-constructed metaphor for Brass' odd, dreamlike commentaries on modern life, sexuality, the church, the Establishment, war...and anything else that comes into Brass' field of vision. Berto Bertuccioli (Nino Segurini), an important executive with the influential PPP (no idea), shows up at a police station to bail out his fiancé, Anita Annigoni (Tina Aumont). Anita, an unbelievably gorgeous student, has been picked up during a student protest, so Berto springs her (due to his connections) and pays off the cops with drugs. Returning to their place, the square, staid Berto asks how it went in jail, which prompts Anita to reenact her gang rape at the hands of the cops (a rape she apparently enjoyed as much as when she recounts it to Berto). Berto schedules their wedding (for the uninvolved Anita), but during the ceremony, Anita catches the eye of workman Coso (Luigi Proietti), and bam: a la The Graduate, she's on a bus and out of there with the handsome stranger/clown/magician.

But this trip to Oz isn't necessarily a happy one, as Anita and Coso go from one strange land to the next, encountering a raging band of arsonist Keystone Kop-like English bobbies, a bourgeoisie couple out for a drive, a sex hotel catering to every perversion, a cannibalistic philosopher ruling over an invisible empire in the woods, a woman who's been crying for a hundred years, a military-occupied city, a lunatic asylum on a deserted island, and finally, a field full of hippies. And very much like Dorothy, Anita returns "home," so to speak, at the end of her journey...but it's not a cause for celebration.

MAJOR SPOILERS ALERT!

Despite unfair (and yes, let's say it: cruel) assumptions by some of my colleagues here at DVDTalk U. (you know who you are), I do not fill my days endlessly watching mindless, mainstream drivel churned out by the Big Three networks during their heyday. I have a very healthy, active foreign/indie life, as well...I just rarely get to write about those kinds of films. So I quite enjoyed myself watching the frenetic, flamboyantly over-ripe L'Urlo. It's not a particularly difficult cult film to "get" (El Topo head-scratchers unite!). Brass makes his large points quite accessible (when two hitchhikers urinate on a crushingly dull middle-class couple's windshield to clear away the mud, we get the point), and anything else is open to one's interpretation...if it indeed those inexplicable moments have any significance or "meaning" outside of pure sensation. In his commentary, Brass discusses the origins of L'Urlo, claiming he went to infamous Italian film producer Dino DeLaurentis with only a couple of vague thoughts about how he wanted to "blow up the screen," bringing a "walking" cinema into step with a "running civilization." Feeling that contemporary cinema would lose future audiences of young people who saw no reflection of their own lives or the turbulent times they lived in mainstream films, Brass wanted to make a movie that was of the times - specifically, 1968 - not about 1968. Thus, a mainstream, traditional fictional story that might have tried to illustrate what it was like for two young lovers to live through the student riots and protests of that crazy year, was jettisoned in favor of a wildly symbolic, avant-garde excursion into surrealism and tactile sensation which tried to capture the emotional milieu of that time, not that time's logic or "facts" couched in a pretend film story. Brass kept the production loose, daily incorporating scenes into the narrative (if you will) based on the filmmaker's feelings about what was happening that day in the world. According to Brass, once the moneymen got a whiff of what was happening on the Italian sets, Brass and company skipped to London where they filmed the rest of the movie (these back-and-forth shifts in locale only help intensify L'Urlo's odd feel). The resulting film caused a furor with the Italian censors, who banned the film for eight years, an act that Brass believes thwarted the career of his star, Tina Aumont.

Brass, trying to make concrete the conflicts he sees between the world we perceive as "real" and the separate interior worlds we all live, presents a "meta-reality" (his word choice) where we all feel more pleasure, more pain, and most importantly, more freedom - good or bad. For Brass, Anita's cry for the impossible to happen, so the impossible becomes possible, is the sole focus of the film. Everything else is pretty much up for grabs, depending on the viewer's outlook (nor does Brass volunteer too many interpretations during his commentary). Utilizing a mixture of black & white and color footage (for budgetary as well as aesthetic concerns), along with newsreel clips of war scenes and rioting, Brass and his co-screenwriters Gian Carlo Fusco, Franco Longo and star Luigi Proietti, disorient the viewer immediately by refusing to film even the most basic establishing shots for both exteriors and interiors, with the spatial arrangements within the sets maddeningly obtuse. In the opening scene, we only get a white blank wall with a fishbowl window to represent the police station - all shot in claustrophobic close-ups. And when Anita and Berto return to their home, we have no idea where it is or what it is, for that matter (it could be a house, an apartment, a loft or a dog kennel for all I know). Once Anita breaks free from her wedding, the film opens up, but it's certainly no more visually reassuring than it was in the beginning (Brass' shots are unkempt and fluid).

Into this flux filmmaking style, Brass is free to insert any number of surreal scenes and visual impressions, some of which support his aesthetic and political goals, and others that may remain inexplicable to the viewer. For example, there's a refrain sung throughout the film, "Break, broke, broken," that I took as emblematic of Brass' stylistic approach to the film: break free from the style of conventional filmmaking by literally "breaking" the screen with unconventional direction and editing choices. Fine. In one of Brass' few explanations, though, he states this is an inside joke directed at DeLaurentis who insisted foreign actors have to learn English (the refrain is started with an unseen narrator describing breaking an egg). Fine, again. My interpretation works, and so does his. I was a little surprised that Brass in his commentary didn't mention a connection, strange as it may seem, to The Wizard of Oz (am I high?), a film that he surely must have associated with on some level for its heavily stylized surrealism. Connections to The Wizard of Oz abound in L'Urlo. Anita dons her wedding dress and is transported out of her drab, dull impending marriage to Berto, and into Coso's world. Helpfully, Coso sports a pair of bib overalls just like Dorothy's first friend, the Scarecrow (Coso also jumps and hops and mugs around like his Oz counterpart). Dual (and sometimes more) roles are there for all the actors of L'Urlo, while Anita/Dorothy keeps asking, "Where are we?" at each new level of unreality, just as Dorothy accepts the fact that she's definitely not in Kansas anymore. I don't think it's a coincidence that Anita wears a metal funnel on her head when she and Coso try to infiltrate the lunatic asylum...just as Dorothy and her friends try and infiltrate the Wicked Witch of the West's castle (and sure enough...not only is there a costumed lion at the hospital, but a real one later at the cemetery, which almost bites Anita - realism trumping fantasy?). And if those parallels don't convince you, how about the scene in the occupied village, where Coso and Anita break into the film sound lab and discover the ominous voice of the military (intercut with newsreel footage of Hitler and Mussolini) is a wind-up dwarf wearing a Napoleon outfit - right out of Oz's final revelation scene? And just like Dorothy, Anita winds up back in her original "reality," her journey of self-discovery over (but one that isn't successful like Dorothy's). Surely Brass was aware of these parallels? If he was, though, he's not mentioning them on the commentary.

As I wrote above, his obvious targets like the Establishment or the church or war are lampooned in scenes that anyone can easily understand (or perhaps it's better to say, "anyone can easily perceive."). Anita's fear of a soul-crushing middle-class marriage is perfectly illustrated when Coso and she are picked up by the bourgeois couple...with the husband played by the same actor who plays Berto (he shows up throughout the film, representing what Anita is running away from). To help drive home Brass' idea on Anita's fate, the husband wears a hearing aid that doesn't seem to work. The sex hotel is an extension of Anita's curious enjoyment of rape (at least her first rape) and her subsequent disquiet over her difficulty in achieving an orgasm (she doesn't take part). An escape into nature proves things are no better out there than in the urban jungle (cannibal philosophers await the unsuspecting - particularly in this case the black missionary they're cooking over a fire). The church isn't going to give you faith, because that comes at too costly a price (Coso smiles beneficently to a nice young man on a dock...and then steals his boat, all while disguised as a priest). As for war, it doesn't take a PhD in Film Semiotics to understand Brass' cross-cutting between a huge cannon slowly rising in the air and shots of Aumont looking indescribably beautiful in black lingerie...after her gang rape by soldiers.

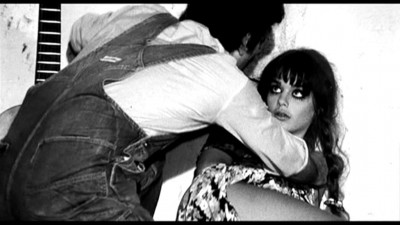

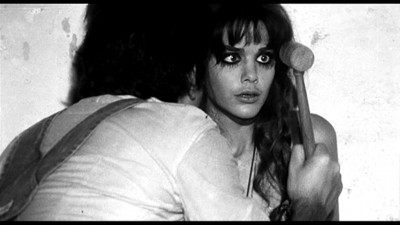

That particular sequence, though, is a good example of the complexity of Brass' technique. Setting up the scene, Anita and Coso become separated in the hellish occupied village where severed heads are adorned on poles and where soldiers roam the streets, looking to massacre anyone in sight. When the soldiers find Anita, they back her into a garage and rape her (off camera), and when she emerges, she's suddenly adorned in an incredibly sexy black number, complete with stockings, garter belt and bustier (which she obviously wasn't wearing before). It's a disturbing transformation that shockingly nails the viewer - just what Brass wanted - for experiencing private thoughts of lust for a woman who's just been raped. Indeed, at the beginning of the film, Brass teases the viewer by interrupting the film and having the occasional unseen narrator say that most audiences would expect a romantic clinch at this spot in the narrative, but since this is a "documentary," no "para-hypo-peri-sexual exercises and gyrations" would be forthcoming. Brass has the narrator say those moments will have to be left to the "filthy imaginations" of the audience. Anita's first rape is shown to be pleasurable for her (she climaxes, and when she recounts it to Berto, she laughs about it), but this one isn't (she runs crying through the streets), and Brass' point isn't one of morality, but one of pure sensation. Whether or not we feel weird about what we're seeing and feeling is our own bag.

Indeed, what we sense and what we feel are far more important in L'Urlo than what we might think about what we've seen. Brass isn't above throwing in amusing moments or elements purely for the inexplicable fun of it... but then you have to pay for them. For instance, the fat hotel clerk who runs the brothel, constantly farting and belching, holds a mouse in his hand who can be heard over the soundtrack squeaking, "Hey, mister, you're hurting me!" - and no one reacts in the slightest to this phenomenon (one of the added surrealistic benefits of the odd-sounding post-dubbed Italian soundtrack). And I have to say that I was paralyzed when I heard that mouse. But then Brass has the mouse killed by the clerk (I don't believe it was actually done on-screen), and it seriously pulls you up short (even worse is the swan that gets decapitated at the brothel - and that is shown on-screen). Are these images meant to shock only, or do they carry other significance? It's up to you to decide. Brass shows us Anita's first rape, and she's clearly enjoying it (she's smiling at the beginning of it, and Brass makes sure we see her climax as the cops' hands slowly caress her face), but what are to make of that previous shot that shows her being violently violated with a night stick? Anita is enjoying that? We're supposed to assume she is? The closest I can come to an explanation for that seeming contradiction - and an explanation, perhaps, for L'Urlo's entire raison d'etre - is that later in the film, Coso recites a poem where he claims to be an idolater, an idolater who loves everything, from life to the bombs that drop during war. Is that what Brass is trying to say? That he loves the totality of all life's experiences, and he's trying to put that on the screen? And if so, how does that jibe with "making the impossible possible" politics of 1968? Is he ultimately rejecting philosophical and intellectual conceits for a purely sensation-based existence? Honesty, I don't know. You figure it out.

The DVD:

The Video:

Cult Epic's anamorphically enhanced, 1.85:1 widescreen transfer for L'Urlo isn't the greatest. To be upfront, I have no idea to what extent the film was restored - at least for content. Brass is watching the film as he conducts his commentary, and there's never a time where he says something is missing, so I'm going to assume this is the complete, uncensored director's cut as indicated on the DVD case. That being said, the actual state of the source material for the transfer is problematic. Some sections look adequate, particularly the black and white sequence where Coso dreams of killing and eating Anita (has there ever been a better-looking actress than Tina Aumont?), while other sections - perhaps the material originally censored? - looks like transfers from second or even third generation videotape. Some of the source material looks horribly scratched, while the video-looking portions sport faded colors and soft, soft images. I wasn't too happy with the encoding Cult Epic attempted with this compromised print, either, with compression issues (interlacing, macro-blocking in the night scenes) cropping up far too often. I stepped down to a smaller monitor, and it helped, but not a lot.

Author's Note: I just received this note from Nico B., of Cult Epic films, concerning the print issues: "Paul, for your information, the print you have seen was composed by Tinto at LVR lab in Rome, to show the complete version, which does no longer exist. The PAL to NTSC transfer creates the interlacing. As well, a commentary at LVR lab was conducted with Tinto in which he tells what was cut."

The Audio:

The original Italian language mono soundtrack is adequate for the job, with hiss noticeable in spots, and English subtitles available (how accurate those translations are will have to be verified by someone who actually speaks Italian...and that's not me).

The Extras:

A big plus for this release of L'Urlo is the commentary track - in English - by director Tinto Brass. He's well-spoken and thoughtful about the production (and particularly eloquent about the late Tina Aumont), and he's not elusive about stating his aims with this mystifying film. Too bad his story about turning down A Clockwork Orange to do this film (yep, Paramount wanted him over Kubrick) comes at the very, very end of the commentary track - I would have loved to have heard that story. Original trailers for Col Cuore in Gola? (Deadly Sweet) and Nerosubianco (Attraction) are included, as well.

Final Thoughts:

Surprisingly accessible for such a weirded-out cult classic, Tinto Brass' L'Urlo (The Howl) is required viewing for fans of the director who only know him for his later sexploitation fare. It's also quite an engaging attempt to marry surrealism with sex and violence to achieve an aesthetic of sensation over linear narrative logic. What you bring to L'Urlo only deepens it. And I don't want to gush, but Tina Aumont is mesmerizingly beautiful here - on a par with the sexiest women in international cinema at that time (or any time, for that matter). Don't buy this if you're at all prudish (full frontal nudity - both sexes - as well as the swan scene). I highly recommend (even with the compromised transfer) L'Urlo (The Howl).

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||