| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Complete Billy Jack Collection (The Born Losers, Billy Jack, The Trial of Billy Jack, Billy Jack Goes to Washington), The

"I just go berserk!"

Image Entertainment has released The Complete Billy Jack Collection, a collection of the four official Billy Jack films: The Born Losers, Billy Jack, The Trial of Billy Jack, and Billy Jack Goes to Washington. Buyers of the previous 2005 Complete release won't need to double-dip here: only the commentary tracks are ported over here. All other extras have vanished, while the transfers are exactly the same. Watching the films in chronological order, they only go downhill in quality (and the first one is no classic), so dedicated Billy Jack fanatics - or nostalgics who haven't seen Billy whup-ass someone in awhile - are probably the best bet for The Complete Billy Jack Collection. Let's look at the individual films.

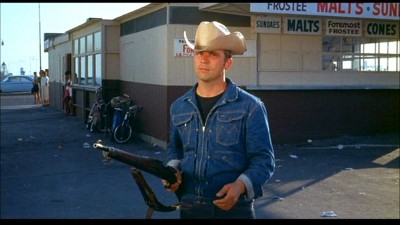

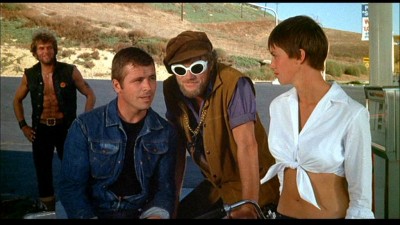

THE BORN LOSERS

High up in the hills above Big Rock, California, ex-Green Beret Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin) has returned from Vietnam to live among nature in his shiny new Airstream trailer. Hunting and fishing and bathing nude in the waterfalls (any other tourists up there, I wonder?), Billy's bid for a peaceful - and isolated - life is already on shaky financial ground, since there aren't any more wild horses up in the hills for the former cowboy to break. Coming into town for supplies (in his shiny new Jeep), Billy runs into a biker gang run by old acquaintance, Danny Carmody (Jeremy Slate). Having beaten a young motorist badly, the gang seems ready to kill him when Billy Jack steps in with a rifle and stops the thugs. For his trouble, though, he's sentenced to a hefty fine for firing his weapon, while the biker gang gets off with much lighter sentences.

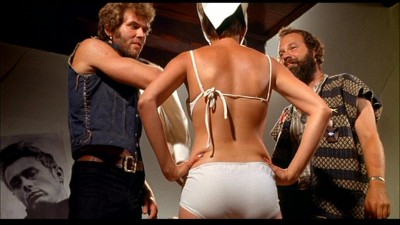

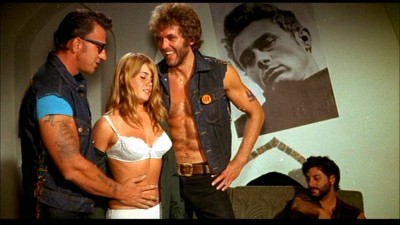

Meanwhile, stacked college student Vicky Barrington (Elizabeth James), disappointed that her neglectful father has canceled their Easter reunion, decides to go down to Big Rock on her nifty white Sears motorbike wearing nothing but a dazzlingly white bikini and matching go-go boots (I feel faint....). Naturally, this attracts the attention of Danny and his gang, and they run this chickie down, eventually daring her to go along with them so she can be "legal" (all she has to do is "turn out" a little bit for the gang)...if she wants. She agrees, and once at their rats' nest of a party palace, she slowly starts to get it that maybe she's in over her head (the two screaming teen girls getting raped is her first big clue). She manages to bluff her way out of the house, and momentarily escape the bikers' clutches, but not for long: she's eventually caught and raped by Speechless (Paul Prokop) and Danny's brother, Jerry (Gordon Hoban). Soon, the town of Big Rock is embroiled in this rape trial (Vicky as well as the three teen girls she saw at the biker pad) of the gang who vow vengeance on anyone who bears witness to their crimes. While the gang systematically threatens the victims and their families, it's left to outsider, karate-chopping Billy Jack to save the girls.

SPOILERS ALERT!

A snappy biker flick with pretensions of social commentary, The Born Losers was, according to the commentaries included on these discs, the fall-back project used to introduce the Billy Jack character when, after 16 years, no studio showed interest in backing the script that would eventually become Billy Jack. According to Tom Laughlin, the Hollywood studios said audiences wouldn't be interested in seeing a picture where the hero was half-Indian (although I question that "fact" from Laughlin, considering quite a few successful westerns were released where the hero was a full Native American, such as Burt Lancaster's and Robert Aldrich's Apache). However, Laughlin's wife (and the producer of The Born Losers), Delores Taylor, was watching a program on television in the mid-60s that detailed a true-life attack by a group of Hell's Angels where gang members raped two girls and then proceeded to terrorize the girls' town, threatening witnesses with their lives if they chose to testify. Taylor felt the story could be easily adapted to the-then emerging biker genre of exploitation films (which really took off with Roger Corman's 1966's The Wild Angels), with Billy Jack inserted as the heroic anti-hero who saves the day. If The Born Losers proved popular with audiences, then studios would be more inclined to underwrite the film Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor really wanted to make: Billy Jack.

Filmed and released in 1967, The Born Losers proved to be enormously successful at the box office (making even more money when it was re-released during the subsequent re-release of Billy Jack in 1973). Watching it today, one can see why it must have appealed to the undemanding drive-in crowd back then. It's quickly-paced (at least until the end of the second act); Laughlin has a good eye for exciting compositions; the action is competently handled, and the girls, shown frequently in their underwear or bikinis, are on display often. Today, the film is cited more often for introducing the philosophical head-bustin' Billy Jack character than for its own role in expanding the popularity of the biker genre, but the film works best when viewed in that context as a straight actioner, and not a socially conscious political statement. If you look too closely past the beatings, the bikes and the babes, the messages put out by The Born Losers are confusing as hell.

Later in Billy Jack, the issues of Indian rights and prejudice between Whites and Indians will take center stage, but Billy Jack's mixed heritage is used in The Born Losers strictly as a catalyst for the action between the bikers and Billy - and a perplexing one at that. When Billy first encounters the bikers beating up the kid motorist, the bikers start throwing out racial taunts about his Indian heritage, and continue to do so throughout the film. But since Laughlin's features don't immediately suggest Native American ancestry, we're puzzled how they immediately attach to him Indian stereotypes (we know he's half-Indian from the opening narration, which is written and delivered in a style to suggest Billy Jack comes from a combination of fairy tale mythology and Phil Spector's Leader of the Pack). Later, Danny lets on that he knows Billy from way back...but that's news to his gang, so again: how did they know he was an Indian? That may seem like a small point, but in setting up the conflict between the two groups, it's an important point to flub through bad exposition.

The Billy Jack character isn't a particularly original one, either, even taking into account his mixed racial heritage (such characters were all the rage in so-called "adult Westerns" in the late 50s and 1960s, such as Audrey Hepburn in John Huston's The Unforgiven). Indeed, his largely silent loner cowboy character, living outside the community that fears him and living beyond the times that have now passed him by (the bank manager uses that exact expression, telling him his time has passed; there aren't any more horses to break up in the mountains), is thoroughly enmeshed in the Western movie tradition. He only talks when necessary; he's pragmatic about his chances in a lopsided fight, but when action is called for, he excels at it - none of that is unique to Billy Jack or The Born Losers. Even his pleas for the community and the cops to help themselves rid their town of the bikers is right out of High Noon, as is the community's refusal to pitch in and fight. When Billy starts to look around for someone to blame, though, that's when The Born Losers starts to get sticky...but again, not too terribly unique.

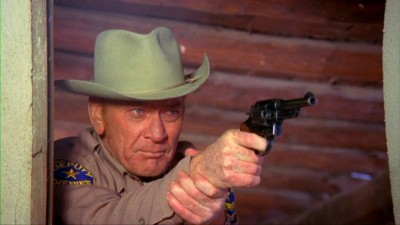

The Born Losers's set-up is straight out of the politics of Dirty Harry: the victims get the shaft while the punks get off scott-free. Billy helps a motorist out of a jam, and he gets a harsher sentence than the bikers who perpetrated the real crime. The system is called "corrupt" and "upside down" (something Laughlin and Taylor agree with in their commentaries), and the cops are shown as ineffectual at best, with a cowardly sheriff who doesn't want trouble and cops who want to make sure a law has actually been broken before they act (when Vicki calls the cops at the gas station and asks for help, they decline because the bikers didn't actually break any laws). Of course the irony of a character that liberal critics took to their hearts (while despising Eastwood's and Siegel's Harry Callahan) is the fact that the decay of the legal system shown here is surely the result of liberal policies - not conservative (you could even make a case that the permissive, absentee parents shown here are also part of a more liberal, less restrictive time when parents were encouraged to be their children's "friends" - especially out in The Born Losers' setting of California). The courts and the legal system have been increasingly weighted to favor and forgive the lawbreaker, with cops being hamstrung by increasingly byzantine restrictions, and with the victim's rights left in the dust. Laughlin and Taylor in their commentaries lament people not getting more involved, but how are they to do that, when cops with their hands tied by endless litigation, an unsympathetic court system weighted with judges who legislate from the bench - and most deleteriously, an army of ambulance-chasing lawyers howling for dollars - await the average citizen who says, after watching a Billy Jack film, "Enough is enough; I'm taking the law into my own hands"? If Billy Jack can't even ward off a biker gang, how can we?

Laughlin's thoughts about the bikers themselves seems somewhat conflicted, as well (certainly in their commentaries, too). While both he and Taylor in their commentaries offer nothing but ebullient praise for the real-life Devil's Disciples club they hired to pose as the film's biker gang ("They were all such nice fellows," Laughlin says), in the film that biker culture is portrayed as one that breeds gangs of psychopathic murderers and rapists who feed drugs to teenagers and then rapes them. That's a hell of a way to say, "Thank you for your cooperation" (apparently some of those guys, who funneled their salaries back into the film's budget to keep it going, were none too happy with Laughlin later, when the film took in millions). Laughlin, in his commentary, said he also wanted to get away from "stereotypes" about bikers by showing that Danny had a child, whom he kindly jostles while his gang watches TV and laughs about raping the girls. Laughlin seems to further soften Danny's behavior by linking the source of his actions to his abusive father, who beats his brother Jerry and spits in Danny's face. Is Laughlin suggesting we feel sorry for Danny and his thugs, because Daddy didn't love them enough; Daddy didn't hug them enough? We may buy that argument when Laughlin applies it to the girls who are shown to have neglectful parents, but we certainly don't accept it for violent, drug-pushing rapists...even if they do have sweet little tow-headed kids around the house.

Laughlin's concern for disengaged parents is also evident, with one of the rape victims, LuAnn (Julie Cohn), going so far as to enjoy being degraded by the bikers (she even goes back for more, visiting the bikers twice after her alleged rape) because such actions represent everything her mother hates. LuAnn forgives the bikers in her mind, and blames Mommy. Laughlin and Taylor in their commentaries suggest this kind of behavior was going on all over America during the late sixties, but I would suggest perhaps the character - and Laughlin the screenwriter - saw Butterfield 8's climatic revelation scene one too many times, instead. I don't really trust Laughlin's take on anything related to sex in this film, because he insists on showing all the victims in various stages of undress; whatever serious messages he may have are blurred by the obvious titillation factor. I don't believe that Laughlin is saying these girls "got what they deserved" because they either dressed provocatively or because they were dumb enough to get in over their heads with the bikers. But he keeps insisting on "dropping his pants and crying rape" (to paraphrase Pauline Kael's criticism of the exciting, supposedly anti-war film, The Bridge on the River Kwai), so Billy's outrage as what was perpetrated on Vicki and the teen girls, is conveyed to the audience in a seriously flawed manner. The most problematic scene in this regard is the further terrorization of Jodell Shorn (Janice Miller), after her first rape. Her mother, played by Jane Russell, has left the house, suspiciously tarted up for her "cocktail lounge" job (is Laughlin saying, "like mother, like daughter"?), so Jodell starts to execute a rather impressive bump-and-grind for the audience, to the accompaniment of music from The Stripper, before she's drawn outside her house by the bikers. When she goes back in (thinking it was only a cat in the garbage), she continues her grind for us, stripping down to bra and panties, before she discovers the bikers inside, who apparently rape her again (or at least sexually terrorize her, because she's left a basket case, sucking her thumb). You tell me what Laughlin means by having the gorgeous Miller dance like that not once but twice for the audience - in perfect full and close-ups shots, with Miller looking right at us - before she's sexually assaulted? If it suggests anything to the more narrow-minded in the audience, it suggests "she's asking for it." Laughlin may indeed not mean that, but why chance that conclusion by including that dancing, in that particular spot of the film, when it's not only extraneous to the scene, but clearly exploitative, as well?

Leaving behind the fuzzy, conflicting politics, The Born Losers as an actioner works quite well, moving rapidly during its first half, with Laughlin and editor John Winfield creating a good amount of suspense over whether or not Vicki will escape from the biker gang (it can be tricky assigning credit to either the director or the cinematographer for nicely-composed frames, but someone had a good eye on The Born Losers). Unfortunately, just when we want the film to really pick up, and have Billy swing into decisive action, the plot doubles back several times, with Vicki in and out of the same trouble, with a protracted, awkwardly staged siege scene at the end that fails to satisfy (The Born Losers could have easily lost 20 minutes or more of its relatively long 113 minute run time to tighten up this last half, such as the pointless dinner with the astrologer). What does help keep our interest during this final section are the characters, particularly Vicki, well-played by the pretty (and pretty hot) Elizabeth James. Unusual for this kind of film, Vicki is admirably articulate about the consequences of her rape when she talks to Billy Jack (you certainly didn't see scenes like that in other exploitation films at the time - a tribute to Laughlin's sensitivities), while Slater provides a good deal of weight as he tries to keep Danny within some kind of recognizable character arc. Laughlin is a tougher nut to crack. Physically, he's perfect as the hard-assed, silent Billy Jack (even his outfit of too-tight jeans and too-small T-shirt and jeans jacket - and even a too tightly crimped cowboy hat - gets across the character's stiff, constrictive nature). And when he's quiet with his minimal dialogue, he's fine - but let him try and be "funny/tough," and it just doesn't work (the "Goldilocks" taunt is embarrassing). Even when playing low-key menacing, it's evident he's trying too hard. Too many Brando-isms start to creep in (his favorite: smoothing his hair down while grimacing), and the actor's natural intensity eventually works against him (be honest: would you really want to hang out with Billy Jack? Not exactly Mr. Laughs). These limitations (in both the character and the actor) don't matter quite so much here in The Born Losers, since Laughlin has the better actor/villain in Jeremy Slate to pick up the slack, but they will be more noticeable in the next film, Billy Jack, where Laughlin is front and center, and largely on his own.

BILLY JACK

"Watch his feet, man. He can kill you with his feet."

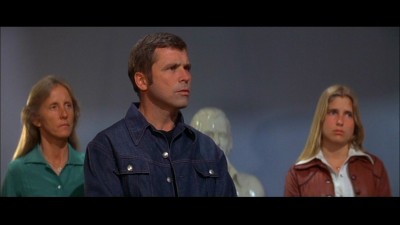

High in the Arizona hills - and illegally trespassing on Indian reservation land - town big wheel Stuart Posner (Bert Freed) has gathered some of his men and sheriff's deputy Mike (Ken Tobey) to rustle and slaughter wild mustangs for the dog food companies. Also along for the ride is Posner's weakling son, Bernard (David Roya), who doesn't want to shoot the horses, despite repeated threats by his domineering father. Right before the butchering begins, though, a menacing figure on horseback emerges from the brush: it's Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin), the half-breed ex-Green Beret loner who lives somewhere in the hills with an ancient medicine man, learning secret Indian ways. Calling out Posner and particularly the bought-and-paid-for Deputy Mike for their blatant flaunting of the law ("When policemen break the law, then there isn't any law. Just a fight for survival."), Billy draws down on the men and forces them to retreat.

Back in town, Deputy Mike's wayward daughter, Barbara (Julie Webb) has finally returned home pregnant, unsure of the baby's father's race, and contemptuous of her father's mixed messages of indifference and concern - all of which enrage Mike who beats her severely. Found unconscious by Billy out on Indian land, Billy takes Barbara to Jean Roberts' (Delores Taylor) "Freedom School," an alternative school for students who don't feel valued at home or in the more conventional educational system. Barbara is cared for by Doc (Victor Izay), the school's physician, and she's welcomed by the school body, including Martin (Stan Rice), a quiet, spiritual Native American who likes Barbara, but who respects her enough not to respond to her sexual advances. Sheriff Cole (Clark Howat) is sympathetic to Barbara's plight - as well as to Jean's "Freedom School" - and he agrees to let Barbara hide out there from her father, but when Posner helps Mike try to find his daughter, tensions rise between the town and the school. Worse, Posner's cowardly son, Bernard, increases his humiliating treatment of various Native American students, until he makes a move against Jean - eventually leading to a violent showdown between Billy Jack and the Establishment.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Anyone who grew up during the early seventies has memories of the character of Billy Jack on a par with that decade's most recognizable action movie icons; he's right up there with John Shaft, James Bond, and "Popeye" Doyle for moviegoers from my generation. And certainly for most kids my age, that summer of 1973, when Billy Jack was re-released to overwhelming box office success, you couldn't get away from the intense marketing hype any more than you could turn on the radio and not hear that god-awful One Tin Soldier schmaltz by Coven every half-hour on the hour ("Go ahead and hate your neighbor, go ahead and cheat a friend. Do it in the name of Heaven, you can justify it in the end. There won't be any trumpets blowing, come the judgment day. On the bloody morning after....one tin soldier rides away." Yeeech.) Watching Billy Jack today, it is so "outside" the experience of catching the film back during its releases in 1971 or 1973 that it's quite difficult to understand just exactly why anyone thought this long, talky, action-sparse, mixed-signals "message" exploitation film was worthy of seeing over and over again.

As I wrote above, the Laughlins introduced the Billy Jack character in their biker exploitation flick, The Born Losers, because no studio would touch their original Billy Jack screenplay. With the healthy box office success of that first biker film, the Laughlins were then able to parlay a deal with AIP to green light Billy Jack, with filming beginning in November and December of 1969. Production was then shut down by the Laughlins when they discovered that AIP was exercising options outside of their contract, with the Laughlins eventually brokering a deal that allowed another studio to buy out the film. That studio, 20th Century-Fox, got production rolling in the spring of 1970, but once again, outside the confines of the Laughlin contract, they began to edit the film prior to Tom Laughlin's final cut (Laughlin insists it was Richard Zanuck, cutting out among other scenes, the town council sequence where characters bad-mouthed then-President Richard Nixon). The Laughlins, independent as always, apparently snuck onto the Fox lot and stole the audio tracks for the film, where they then threatened to erase one reel a week until the film was returned to them. Fox had no alternative but to acquiesce, and Warner Bros. stepped in to release the film in 1971. Now, here's where stories begin to conflict. The official version is that Warners didn't properly promote the film during this first release, and that a low box-office led the Laughlins to sue Warners over the botched handling of the film, with the couple eventually winning the right to control the re-release strategy (with Warners sharing the actual distribution duties). But several sources I've read indicate that this first release was still enormously successful (historian Danny Peary puts this first gross at over 30 million - phenomenal for 1971 standards), and that the Laughlins sued because they felt even more money could have been made from the film (I wonder if the real reason was profit-participation, since Warners had bought the film outright from the Laughlins, and considering this first incredible gross, the Laughlins were feeling shafted). All accounts do agree at this point, though, that once the Laughlins and Warners settled out of court, a new release was planned, utilizing not only a saturation publicity campaign (I remember the radio ads being almost non-stop), but also the unheard-of (at least for a major studio release) practice of "four-walling" Billy Jack. With "four-walling," Warners and Laughlin would jointly rent movie theatres outright in various markets, and collect 100% of the ticket grosses (the theatre owners only received the rental fee, along with their concession sales). The risk was enormous - if the movie tanked, the studio and Laughlin were stuck with expensive rented theatres and no patrons - but if the movie clicked (and how couldn't it with the massive, catchy ad campaigns?), the profit potential was staggering. And indeed, the marketing campaign, emphasizing Billy Jack's counter-culture chic allied with ass-kicking actioner cred, resulted in even a higher gross than the first 1971 release...with plenty of coin this time going directly in the Laughlins' pockets.

I detailed the film's hectic production and release history because I think it goes a long way towards explaining the film's popularity. If you listen to the commentary tracks on these DVDs, you'll hear the Laughlins describe the Billy Jack character as a legitimate source of idolatry for young filmgoers who, according the Laughlins, responded to the film's political messages, and kept coming back for more. And that reason may very well have been true for a number of patrons who continued to buy tickets for the film. However, my experience with the film - particularly during the 1973 mega-hyped re-release - didn't have a thing to do with politics...and I suspect neither was it so for my older brothers, or my friends, or their parents who were dragged along to go see this "must-see" film of the year. It was the marketing - specifically: Billy Jack was touted as a "new kind" of Western/action picture that upturned the traditional cowboy hero by making him a counter-culture "half-breed" (the film's term) and an ex-soldier, who used the Asian art of hapkido (we called it karate) to decimate his foes. The marketing campaign hit on several major hot-button issues at that time - the Vietnam War, Indian affairs (the Wounded Knee incident of 1973 had captured headlines for months at the beginning of the year), women's rights, minority rights - while over-inflating its action credentials. In particular, after the standard drive-in exploitation angles were covered (Jean's rape, the film's brief nudity), Laughlin's use of martial arts took on new significance in 1973, since Bruce Lee's popularity (and notorious early death) had caused a world-wide explosion in popularity for the sport. All of these factors contributed to a feverish marketing campaign that hit practically every conceivable demographic and created a palpable sense of anticipation for the movie that was touted as causing so much trouble for "the Establishment" (certainly the film's troubled production and first "botched" release was a factor - again, was the "botched" angle specifically created to generate fodder for the re-release's publicity?). Were kids actually going around preaching Billy's credo and changing their lives, as the Laughlins suggest, or were they more likely acting out his hapkido moves on the playground...or going over them in their heads while they tried on that new Wrangler jeans jacket that looked just like the one they saw in the film?

I certainly have my doubts as to how widely influential Billy Jack was on a political and sociological level for its patrons, but if it was, I have to wonder what kind of head-scratching went on in theatres as kids and students tried to follow just what the hell was going on inside Billy's and Jean's noggins. Technically sloppier than its predecessor (which wasn't exactly a model of proficiency, either), Billy Jack's political meanderings are as choppy as its exposition. And it's hardly the "original" that its creators claim it is - either in its message or its execution. Billy Jack's emphasis on showcasing the differences between emotionally distant parents and searching, spiritually lost kids, between political wheeler dealers who control men and their towns, and the loners and outsiders who have to fight the system, weren't exactly novel concepts in 1969-1973 (you could get the same story elements out a handful of Mod Squad episodes). In the DVD commentaries, you can hear the sincerity of the personal beliefs the Laughlins hold, but regardless of whether or not you agree with the validity of those beliefs, it quickly becomes apparent that their limited scriptwriting and filmmaking skills only further obfuscate their already fuzzy thinking when it came to getting their messages across through Billy Jack.

While I happen to believe that the main purpose of Billy Jack is manufactured mythmaking to realize a commercially viable film, if you try and follow the logic of the film's interior, you quickly get lost. A good example is the town council sequence. Many critics pointed to this scene as one of the film's strongest moments, where the students express loud, pointed contempt for the council's arbitrary actions concerning the "Freedom School's" ability to function in the town, and to be fair, Laughlin does capture a free-wheeling feel of give-and-take, aided by stocking the crowd with members of the improv group, The Committee, and by letting some real councilpeople throw out lines among the actors (interestingly, one real councilwoman states the meeting shows both sides in less-than-ideal lights). But then Laughlin's "solution" for the meeting is to have the wary council invited out to the school to see the kids in action, to which they are then treated to an incredibly lame skit by The Committee involving drugs. I thought "no drugs" was rule number one at the "Freedom School?" If so, why are they a source of amusement, and why present that skit as representative of the school? If Jean wanted to impress the council and reassure them that the kids are involved in meaningful, spiritual pursuits, why not let the actual kids perform, instead of obviously adult "students" like Committee members Allan Meyerson and Howard Hesseman (and Richard Stahl as the head of the council, who also takes part in the skit)?

Indeed, that kind of addled padding is present throughout the middle of Billy Jack, and it's a crucial miscalculation in establishing the "Freedom School" as a believable entity, as well as establishing a meaningful set-up for the film's central conflict. After all - why is Jean continuing to lament the town not understanding the school...when the council members leave the demonstration satisfied and happy that the school is doing good work? Doesn't their "guerilla street theater," complete with Sheriff Cole's cooperation, also generate an appreciative crowd (if the answer to social harmony is more "guerilla street theater" such as showcased here, then the wrong heads are getting busted in Billy Jack)? So if we don't believe the "Freedom School" is truly threatened by the town, we don't believe Billy Jack's and Jean's continued actions directed at "saving" the school - and there goes your whole movie. While it was relatively unique to see the Laughlins try and inject an even-handed humanism to not only their heroes but their villains in the exploitation filler, The Born Losers, such efforts aren't any more successful here than they were in that film. Jean is labeled a pacifist, but her feelings for the violent, often uncontrollable Billy are confused at best. She hates his fighting, but she admits she likes the fact that others are scared of Billy, so no further harm will come to the school. She keeps telling Billy he can't make his own laws, but she keeps excusing his behavior when he does make his own laws. She knows she shouldn't let the students go into town, but she wants them to make their own decisions, so ...she keeps quiet and lets them go into town - a most irresponsible action for a teacher/parent (an action, by the way, which negates her calling out Billy during his last siege with the cops, when she says she put her kids first rather than tell Billy about her rape). Certainly, character complexity is a desirable end, not a fault, in a film, but Billy Jack has been sold (and continues to be sold) as some kind of parable for kids to emulate, a life-changing experience that also happens to exude an exceedingly smug, self-satisfied tone about its propositions...propositions that sound half-baked, facile, and contradictory - not complex or shaded.

And nowhere is that smugness more pronounced than in the central character himself, Billy Jack. His character shielded by the cloak of Native American spirituality (a spirituality that's presented as unassailably positive while remaining largely unexamined for faults, while Christianity practiced by Whites is singled out as incompetent and devoid of true spiritual depth), the Billy Jack character may whine a bit more about his feelings, but he's truly not that much more evolved from Eastwood inexpressive killing machine, The Man With No Name. A mass of contradictions that are continually called out in the film but never looked at too closely, Billy is led to temporary madness when he see what Bernard does to the Martin and the other Indian students at the ice cream shop (Bernard pours flour on them to make them "White"), but later, when Bernard almost rapes a student at knifepoint in his Corvette, Billy and Jean literally chuckle and shake their heads at his shenanigans (perhaps their attitude comes from the fact that this older White girl is presented as sexually "loose" - which only makes Billy's and Jean's reaction more contemptible). Billy laments the fact that great leaders are shot down in America because there are no gun laws...but he rides around with a lever-action carbine which he freely pulls on anyone who gets in his way. Jean refuses to tell Billy he must get Cindy out of harm's way during the police shoot-out; thus her continued inability to make a decision is no more surprising than Billy's earlier stated credo that allows Cindy to hang out while the bullets fly: "What will be, will be" (See? Even that's not original to Billy Jack - Doris Day sang it first, folks). Billy is upbraided by Jean for his drama-queen heroics during the final shoot-out...while his admirers throw him the Black Power salute as he's lead off in chains (what "victory," exactly, are they saluting?). We're supposed to feel that Billy's rage is as inexplicably dark and mysterious as his secret Indian training up in the hills, but often times, he comes off as a petulant child who isn't fighting personal demons as much as a bad case of pique and immaturity. Prior to the final fight, he dares Jean to name one place on earth where man loves his fellow man, and when she can not, he leaves in an "I told you so!"-like huff to carry out his violence. Watching this scene, a viewer can't decide who's more clueless: Jean, who could certainly at least point to her own school as an example, or Billy, who, after all that spiritual training, can't say, "The entire world, actually," since love and hate co-exist together in any human society, not in separate voids (cripes, your average Sunday School student could have parlayed that mind-blowing concept to you, Billy).

Of course, Billy's ass-kicking philosophy in the name of peace is the one thematic element that skeptical critics and audience members always immediately latch onto with the character, but for me, that aspect of the film isn't deserving of much more than an afterthought because Billy Jack has so few action scenes - and that, ultimately, is the film's biggest cheat. As the Laughlin's correctly point out in their commentaries, Jean was the pacifist, not Billy; Billy struggled (however incoherently) with his violent demons throughout the film. So he's basically absolved of all responsibility towards pacifism; he can head-stomp with abandon and chalk it up to "personality conflicts." Where the film truly cheats its audience is in presenting a scenario and repeated set-ups that promise action - that's certainly the angle that was promoted in the marketing campaign, as well as the totally inexplicable cache Billy Jack once held as one of the great martial arts films of the '70s - only to fail to deliver them, falling back on endless talk. Frankly I was shocked, not having seen the film in decades, at the paltry amounts of action in the film - a sentiment echoed by Tom Laughlin himself when he realizes there's really only one major fight scene (somehow, I remember an ass-whompin' every ten minutes or so in my "memory Billy Jack") And while that particular sequence is well choreographed and executed (although the magic of DVD's clarity now permanently ruins the illusion that it's Laughlin himself doing the difficult kicks; we can now clearly see it's Laughlin's martial arts advisor, Bong Soo Han, doing the trickiest moves), it's nowhere near the duration nor the intensity of a random five minutes from any Bruce Lee action sequence. And it's not enough to give the "okay" to this sequence, as Laughlin does in the commentaries, because it's the "first American martial arts film," as he states - which isn't even technically true. Considering how short the main fight sequence is here, you could say Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate could qualify then as the "first" in America, with its still-terrific fight scene featuring Frank Sinatra (you might even make a case for Cagney's 1945 Blood on the Sun, or Gary Cooper's 1946 Cloak and Dagger -- both of which featured some cool judo sequences. Or how about Sean Connery's 1967 Bond epic, You Only Live Twice, made with American money?). No, Billy Jack "cheats" because it's clearly designed as an exploitation film, and its scenes are arranged and tempoed to lead to numerous action scenes, and yet it pulls back time and again, and denies the audience those moments, instead falling back on endless dime-store philosophizing and cheap-jack dramatics. One could say Billy Jack's confusion over what kind of film it is (or should be) is just as endemic as its characters' schizophrenic bewilderments and its thematic political and sociological puzzlements. And things would only get worse with the next installment in the Billy Jack saga.

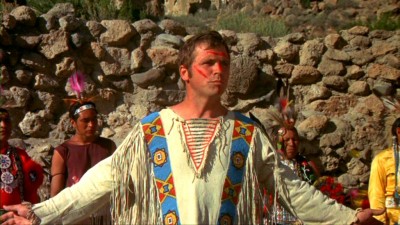

THE TRIAL OF BILLY JACK

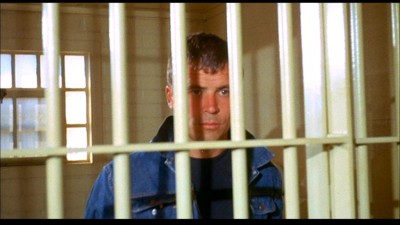

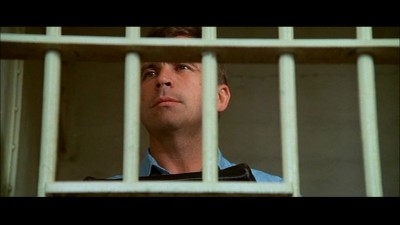

As an eagle flies over Monument Valley, the dead and wounded in various college campus riots are listed. Fade up to Jean Roberts (Delores Taylor), founder and president of the "Freedom School," laying in a hospital bed, recovering from several gunshot wounds. Talking to a reporter about how the massacre at the "Freedom School" went down, Jean recounts two separate but ultimately intertwined stories. First, Jean recounts the trial of Billy Jack for the murder of Bernard Posner (see Billy Jack). Billy gives an accounting of his eventual "break" with the United States due to his witnessing a My Lai-like massacre of civilians during the Vietnam War - and America's subsequent support for the guilty officers as well as President Nixon's refusal to investigate the crimes. He's convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to four years in prison.

Meanwhile, the "Freedom School" thrives from the publicity generated by Billy Jack's stand against the police. Eventually, the school finds new digs (in a converted military base, naturally), and through donations, music sales of Billy Jack protest songs, marching band contests and one would assume a whole lot of bake sales, they also manage to build their own TV station, where the students start digging up muck-racking exposes against the Establishment authority figures who rape the land and bleed the citizens dry. Unfortunately, this kind of grass-roots political activity doesn't sit well with the corrupt Federal government, which immediately starts tapping the school's phone lines and conducting surveillance on the student body. After a side-trip for a discussion on child abuse, we're brought back to the saga of Billy and Jean, when Billy is finally released from prison and reunited with his first loves (that would be Jean and himself).

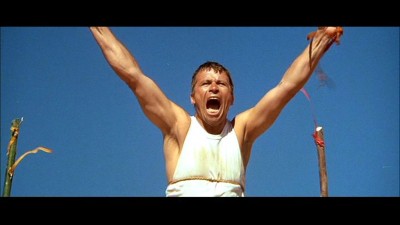

Billy's triumphant return to the "Freedom School" is immediately marred by the disappearance of two hikers up in the snowy mountains. Helping to locate them, Billy is ready to perform minor surgery on the surviving frostbit hiker when the hospital refuses to treat the Native American, but he's relieved of that duty when Doc (Victor Izay) shows up and takes charge. After the hiker is charged with trespassing, while town fat cat Posner (Riley Hill) hosts a debauched retreat for other bigwigs like the Lt. Governor on Indian reservation land now "terminated" with no consequences, Billy and his Native American brethren decided to photograph the influential high muckety-mucks in an effort to shame them. Tensions build again between the town and the school, but Billy Jack is nowhere to be found, having gone upon the mountain again to take the terrifying "Inward Journey" in The Cave of the Dead. As Billy confronts his personal demons yet again, Jean must deal with the television station being sabotaged, and the townspeople's prejudice against the school, with a horrific confrontation between the military and the school the end result.

SPOILERS ALERT!

An unwieldy mess of a film, clocking in at almost three hours long, The Trial of Billy Jack is fascinating none the less just to see the Laughlins' marriage of sheer megalomania with crass commercial considerations thrown up on the screen in an ungodly epic format. Unbelievably incoherent, The Trial of Billy Jack is almost impossible to discuss in terms of content, because its form is so overwhelming and intrusive. There is little logical flow from sequence to sequence, or even scene to scene, but once its intentions are finally sussed out amid the endless dross, its final impact is remarkably muted. Clearly two entirely different films awkwardly combined as one, The Trial of Billy Jack looks not only at the continuing mythologizing of the Billy Jack character (here finally attaining - with a straight face, no less - a god-like level of awareness and power), but also the final corruption and defeat of the sixties youth movement through the manipulated and manufactured massacre at the school. Along the way, we're treated to extended looks at the problems of child abuse, the corruption in the Bureau of Land Management, Indian rights, the criminality of covert Federal spying agencies, and of course, hapkido demonstrations, all of which might have made interesting subplots if some kind of directorial and editorial choices - and hard ones, at that - had been made. And this isn't just coming from me: Tom Laughlin, to his credit, speaking on the DVD commentary, repeatedly cops to the film being entirely too long...and not particularly well structured or written in his opinion, either.

According to Laughlin, The Trial of Billy Jack was produced as a direct response to the student riots that were happening on college campuses in the late 60s and early 70s. Fair enough: that's a subject worthy of a big film. But soon, various plot elements and thematic asides begin to overwhelm the film's focus, with the viewer jerked back and forth between sequences that refuse to flow into each other. The Laughlins' take on the campus troubles is seemingly summed up by Jean, who in her hospital bed, states, "Students are slaughtered by trigger-happy police types and nothing is ever done about it," a statement that seems to indict a perceived mindset as well as an entire segment of the population: the police/military. This is further emphasized during a scene where the cops hassle the "Freedom School" kids in town, going so far as to beat up one for daring to suggest he'd rat them out for their unlawful behavior (Billy Jack comes to the rescue in a dispirited, anticlimactic fashion: he doesn't even fight the cops; they just run away). Certainly, the beginning of the film touches on Billy's revulsion for the United States government in general, when he recounts his "break" with America after he witnesses a My Lai-like massacre in Vietnam, and when he says the American public rallied behind the killers, with the politicians doing nothing about it. But later, The Trial of Billy Jack starts to blame government agents for fomenting dissent and actively starting the riots in an effort to shut down exposes of crooked federal deals, while the average law enforcement officer or solider is shown as merely an innocent pawn in the high-stakes games between corrupt officials (the William Wellman, Jr. solider who has a nice family, and who doesn't want to take part in the massacre...only to wind up accidentally shooting the little boy with only one hand). As usual with the Laughlins, this seemingly even-handed approach may suggest complexity of characterizations, but up on the screen, it comes across as merely perplexing intellectual vacillation, made even more schizophrenic by their haphazard moviemaking technique.

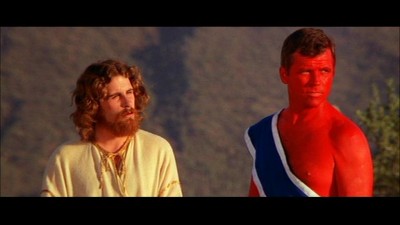

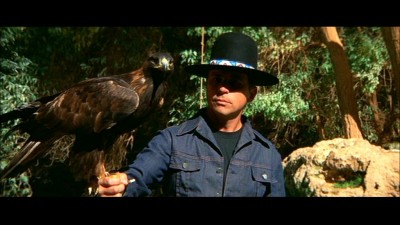

The Trial of Billy Jack is such a strange film because it so desperately wants to be not only "about something," but "about something on a grand scale," and yet it feels remarkably small and limited despite its form. Endless talk certainly doesn't help matters here, particularly when most of the dialogue is written for signpost obviousness on subjects that seem, at best, tangential to the task at hand. And the scenes themselves, except for Billy's spiritual journey into the Cave of the Dead, come off as stilted and constricted, and certainly not "epic" in either conception or execution (with the exception of the desert scenes, which did achieve quite a majestic beauty by cinematographer Jack A. Marta in the first Billy Jack film shot in 2.35:1 widescreen, the rest of the film looks surprisingly dingy and cramped). The mythologizing of the Billy Jack character reaches truly ridiculous proportions here, with Billy likened to a god in many scenes (when Billy first meets up with Jean, he stands still by a river as a wild eagle, from out of nowhere, suddenly lands majestically on his arm, as if called to by his master). Billy's eventual decision to take the "terrifying Inward Journey" in the Cave of the Dead is probably the film's most compelling sequence (unfortunately marred by constant cross-cutting with other subplots - the film's editorial hallmark), even though its resolution is badly handled (Billy meets his own worst enemy - his shadow self, which is Laughlin again but now in bright blue makeup, looking rather Smurf-like - before a "spirit guide" takes him on a tour of badly-staged "tableaus" out in the middle of the desert, illustrating the various levels of enlightenment a man must go through). All of this spiritual awakening comes to naught, though, because how can Billy Jack "be" the Billy Jack of the movies if he achieves total enlightenment? How can we have a "Billy Jack movie" if Billy doesn't blow his cool and start busting heads? Of course, that's the central cheat of all the Billy Jack movies: action that contradicts "message" in the service of commercial viability.

There's a noticeable increase in action in The Trial of Billy Jack over its predecessor, Billy Jack, but that welcome addition is negated by the film's excessive length. If there were any doubts about the motives the Laughlins may have had for including violence in a film like Billy Jack that espouses non-violence, those doubts are laid to rest in The Trial of Billy Jack. The central fight scene, which is fairly well-staged, with one incredible moment where a stuntman takes a horrendous two-story fall on his neck, is merely an excuse for Billy to reject his teachings and go against the spiritual enlightenment he supposedly attained. The final massacre of the students, however, is pure, calculated exploitation - regardless of any protestations to the contrary as to its good-will intentions. Certainly the violence is nothing compared to today's films, but the sight of a one-handed boy - holding a bunny, for christ's sake - getting shot down by a soldier, has absolutely nothing to do with the Laughlins' wobbly diatribe against the powers-that-be, and everything to do with fashioning a remarkably crude (and intellectually suspicious) emotional moment. Even more incredulously, the filmmakers have the nerve at the end of the film to indict the audience for any potential criticism they may have towards the depiction of violence in the film, stating we're all accomplices: such goofily wrong-headed chutzpah I have never seen in a filmmaker before The Trial of Billy Jack.

Then, once you realize that The Trial of Billy Jack will be more of the same as Billy Jack - far too much wonky talk and far too little hapkido - the viewer has to fall back on trying to make sense of the never-ending dialogue scenes. Jean says Billy was really put on trial because the Establishment wanted to quash "each man's right to find his own center...to do his own thing." Billy states Death is his constant companion who frees him from worries of trivial things but allows him to appreciate each moment (but I thought everything ticks off jittery Billy?). Billy says the "American consciousness is dead," and that the "spirit of Boston and Virginia could never be revived." Jean invokes the memories of our Founding Fathers, as well, in a pointless scene about child abuse (today, she'd be pilloried for praising slave holders, no doubt), and later says what she does at the school could quite literally save the world (a megalomaniacal moment in the film that would make Jerry Lewis weep with envy). Jean states winning or losing or getting good grades aren't important at her school (remind not to fly in a plane engineered by one of her students), and Billy is serenaded by a student who warbles - without a trace of irony, and with a straight face - "Are you crying, are you dying, just for me, Billy?" Later, Billy attacks the history of White Christianity, citing abuses by St. Augustine, Richard the Lionhearted and Kit Carson (yup - those three pretty much cover the whole of Western civilization), while of course failing to mention inconvenient truths about Indian massacres, Indian slave holdings, and Indian atrocities (doesn't fit in with the P.C. Muzak). We're told to love child abusers, because yelling at them or punishing them doesn't work, while Jean tells us, "Where there is power, there is no love. And where there is love, there is no need for power." And finally Running Bear screams, "Congress is a bunch of filthy, rotten, lying thieves!" (the sole voice of sanity in this film). All of this blather would be comical if the film itself didn't take such a ridiculously straight-faced, insufferably smug attitude towards its messages. I have no doubt that the Laughlins believe in their causes they discuss on the DVD commentaries, but I also firmly believe that the Billy Jack movies aren't the pure exercises in hoped-for social engineering the Laughlins would like us to believe. These are calculated efforts designed to exploit buzz-worthy subjects, with head-whompin' thrown in to jingle the box office cash boxes. It's a preachy commercial mix that certainly worked in terms of box office in Billy Jack's case, but one that seems forced and bloated and patently false here (accounts vary as to how successful The Trial of Billy Jack was: some say it was a substantial hit, due to its saturation bookings across the country - a first for this kind of studio film - while others say it debuted strongly then tanked). What a shame that Laughlin couldn't leave the lofty, phoney pretensions of the character behind, and just embraced the "badness" in Billy Jack; he might have come up with a kick-ass movie that entertained its audience (while still subtly slipping in a message here and there).

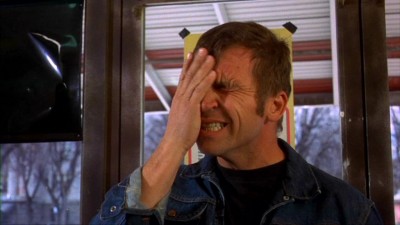

BILLY JACK GOES TO WASHINGTON

When Senator Sam Folley (Kent Smith) drops dead after illegally closing hearings concerning the building of nuclear power plants, aide Dan McArthur (John Lawlor) swipes the Senator's sensitive file on all the nuclear goodies and high-tails it out of there, leaving fellow aide Saunders McArthur (Lucie Arnaz) behind to clean up the mess. Soon, the phones are ringing in Washington, and Folley's fellow Senator, Joseph Paine (E. G. Marshall), calls up Governor Hubert Hopper (Richard Gautier) to see who can be placed in Folley's stead so as not to gum-up the works of the top secret nuclear plant deal cooked up by Paine and his longtime political "boss," magnate Bailey (Sam Wanamaker). Bailey and Paine want someone safe and controllable, but Governor Hopper somehow gets it into his head that pardoning Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin) and appointing him interim Senator would be a wise move politically, and before you know, Billy Jack Goes to Washington.

Of course, once there and finally bedecked in all his Billy Jack finery (his one concession to decorum? He doesn't walk around the Senate building barefoot), Billy finds out how corrupt Washington truly is, and wonders who the hell he can punch to set things right. Unfortunately, such actions would result in immediate expulsion, so Billy has to settle on the CIA hit squad who are sent to take out one of Billy's aide; evidently, Billy's muck-racking team is unearthing nasty truths about government - and the corruption surrounding the nuclear-power industry - that are making some higher ups very nervous. Soon, Dan is found belly-up with a shiv stuck in him, and Billy Jack is next as he discovers the secret behind Paine's dirty deals with Bailey, bringing Washington to a halt as he filibusters the Senate.

SPOILERS ALERT!

Legendary among high-profile flops, Billy Jack Goes to Washington is the easiest Billy Jack movie to deal with...because it's barely a Billy Jack movie at all. Ostensibly a remake of Capra's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the Laughlins throw in some trendy updates (such as the nuclear power angle, along with discussions about how bills are made and broken by Washington corruption), but it's close in spirit to the original story...if miles and miles away from the technical and aesthetic proficiency of that first film. The Laughlins, in their commentaries, state the film was never officially released (although curiously, in an old reference book I have for movies from Consumer Reports, they list feedback data and ratings for the film from readers who claim to have seen the film), although I've read where it had some premieres. According to the Laughlins, Billy Jack Goes to Washington was scuttled by the powers-that-be in Washington, who warned distributors away from the film out of fear its message would jeopardize their covert set-up with the nuclear power industry.

I have no idea if any of that is true or not, but I can say, with complete and utter conviction, that had Billy Jack Goes to Washington been released to theatres, there would have been a whole lot of disappointed Billy Jack fans out there. Not that there's a whole lot of "Billy Jack-ness" in the first three movies, anyway, but by the time Billy Jack Goes to Washington rolls around, it's hard to see where Laughlin was trying to go with this character. Forget the fact that the central premise of the film makes absolutely no sense. What corrupt politician in their right mind would appoint convicted troublemaker Billy Jack - a known and willing crusader against corrupt government - to the role of State senator with the idea that he could be safely handled? If you watch the film, keeping the associations with the previous films in mind, you can see what a ludicrous idea this is to hang a film on. And if you don't buy the central plot device that gets Billy Jack to Washington, it's a tough slough through the movie-of-the-week dialogue and the flat-as-a-pancake direction (and when you see four principal editors credited to a film...look out; that's the kiss of death).

Making the Laughlins' limited filmmaking skills even more pronounced this go-around is the sight of a couple of truly great, professional actors showing up here - a real rarity with the Billy Jack films where non-professionals can dominate. E.G. Marshall and Sam Wannamaker have a couple of good scenes together where they dominate the banal dialogue, giving their moments an added level of believability that certainly isn't warranted by the material (it's great to see legendary Pat O'Brien, as well, in one of his last roles - pity it wasn't larger). But Delores Taylor - who was probably the best thing in Billy Jack -- is cut back severely here, while Lucie Arnez pops in and out of the movie with ineffectual regularity (her "big" scene where she screeches at Billy about Washington corruption, is quite simply, an embarrassment for all concerned). And Tom Laughlin fails to find anything new to do with the Billy character, limited as he is by the film's setting to let Billy Jack bust some heads in the plot (one fight scene is included, but it's cut off fairly quickly). Laughlin, never the most expressive actor, looks quite bored, actually, in most of his scenes, as if he's preoccupied going over in his head all the overages his production company created when he built a ridiculously expensive recreation of the Senate chambers. Eventually, the film gives up trying to be a Billy Jack movie and settles down into a rather conventional remake - a remake whose sole achievement is making the viewer long to watch the original inspiration. With the disastrous failure of Billy Jack Goes to Washington, the Laughlins' film empire came to an end (the commentary is vague about exactly how much they suffered financially because of this bomb). An aborted attempt to film a fifth Billy Jack film was attempted, I've read, in 1985, but by all accounts, it remains unfinished. And with the remaining audience that even remembers Billy Jack, getting older by the day, I doubt we'll see any further adventures.

The DVDs:

The Video:

The Complete Billy Jack Collection utilizes the exact same transfers as the previous "Complete" collection, with The Born Losers and Billy Jack presented in anamorphically-enhanced 1.85:1 transfers, and The Trial of Billy Jack and Billy Jack Goes to Washington presented in anamorphically-enhanced 2.35:1 widescreen transfers. While the transfers themselves look quite good (I didn't notice any compression issues), the source materials used have evidently been cleaned up to some degree, as well. Scratches and dirt are still present to a small degree, as is grain, while the colors are fairly bright, with sharp images. These look as good as you're probably ever going to see them, and they're miles above previous full-screen releases and television presentations.

The Audio:

You can select a newly-mixed Dolby Digital English 5.1 track for the various films (strong levels, but not an overabundance of separation effects), or you can listen to the original big, fat, 2.0 split mono tracks if you're feeling nostalgic. Subtitles or close-captions are not included, unfortunately.

The Extras:

The big difference between this collection and the previous "Complete" collection is that all of the extras have been stripped away except for the 2000 and 2005 commentaries by Tom Laughlin, Delores Taylor and Frank Laughlin that are included for each film. No trailers. No galleries. No documentaries. Listening to the commentaries, I found almost no difference between the two, except for the occasional additional anecdote about filming a particular scene. Most of the stories were the same from one commentary to the next, for each film. One curious note: the commentaries were "off" by a few seconds for each film; the Laughlins would be describing something that hadn't happened yet on the screen. Distracting at times.

Final Thoughts:

How can you not watch at least Billy Jack? If you want to understand early seventies American movies, it's one of the titles you probably should catch - but you've been warned. There's no need to double-dip on The Complete Billy Jack Collection if you already have 2005's Complete release in widescreen - there were more extras on that set. The films do look good in their anamorphic transfers, and the commentaries are...interesting, to say the least. Unless you walk around in that hat and jeans jacket, man, I think a rental is best.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography .

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||