| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Complete Jean Vigo, The

Please Note: The images used here are taken from previously existing sources, not from the Blu-ray disc under review.

"Freedom comes at a high price, and it's very rare. There are maybe ten free men in the world. Jean Vigo was a free man and, as such, he set an example." - Jean Painlevé, colleague and friend of Jean Vigo

The story of French filmmaker Jean Vigo's tragically short, venerable, groundbreaking career has its parallels with that of Orson Welles, but it is much crueler: Whereas Welles faded in and out, haunting the silver screen for decades after Citizen Kane, Vigo (unintentionally) burnt out. His passion for cinema having led him, despite his physical frailty and ill health, to brave the elements while filming his great, sole feature, 1934's L'Atalante, he developed tuberculosis and died at the tender age of 29, before he could put what surely would have been further transporting visions onto celluloid. His reputation as an innovator, master, and prophet of the cinema has remained intact for 80 years now, even though he left only enough work for a very short retrospective. That body of work is an absolutely essential one, and Criterion has finally brought it to us on a Blu-ray compilation that has a long-reserved place on the shelf of any serious film lover.

À propos de Nice

Co-directed by Vigo and Boris Kaufman (who would remain Vigo's cinematographer on all four films before going on to a remarkable body of work of his own, shooting such other notable projects as On the Waterfront and 12 Angry Men), À propos de Nice is a freewheeling, 20-minute quasi-documentary shot, obviously, in the environs of the popular resort town on the French Riviera. The film has a flowing, sensual, seemingly spontaneous quality that would become one of Vigo's trademarks; it resembles in that way Dziga Vertov's contemporaneous Man with a Movie Camera. (It is surely no coincidence that Kaufman was Vertov's brother.) But the film is structured in such a way that, despite its apparently free-form approach and absence of narrative, it has a discernible progression and didactic/revolutionary aim.

Our introduction to Nice as the film begins is the metaphorical, completely unexpected appearance of two human figurines who are raked onto the craps table of one of the town's casinos by the dealer's swift hand. We then cut to the hectic street life of Nice, packed with real human figures who have been drawn into this seaside playground for the idle rich. These representatives of the leisure class shop, dance, and lounge, exhausting themselves with the heat and their bored, manic pursuit of pleasure. We then segue into a sequence in which Nice's actual residents--street urchins, washerwomen, working men--are seen in various states of work and play. Finally, there is a scene of Nice's carnival parade that becomes increasingly intense--almost joyfully apocalyptic--suggesting the disruption, blurring, and overthrow of the wealthy-bourgeois/working-class binary order that has come before.

None of that is to say that À Propos de Nice is straightforward or programmatic with its decidedly political point of view; it would actually be difficult to match its degree of playfulness and spontaneity. Vigo and Kaufman play with some instantly memorable technical experiments--slow motion, disorientingly low angles, and the like. In one especially memorable, lovely moment (which rhymes, in its juxtaposition of human beings with human symbols, with the figurines from the film's opening), the power of photographic effects transforms a pretty young woman into a sort of paper doll as one outfit after another appears to "fade" on and off of her, finally leaving her as nude as an artist's model.

À propos de Nice is only the first instance of Vigo's insouciant cinematic poetry, but one would not consider it an example of "raw" talent or merely "interesting." It is a fully realized effort, sophisticated in its playfulness, that is as fully achieved, in its miniaturized way, as Siodmak and Wilder's People on Sunday or Réné Clair's En'tracte, and a film that any auteur would be proud to have for a debut and calling card.

Taris

Vigo's next foray (which in the credits has the longer but more descriptive title of La Natation avec Jean Taris, or "Swimming with Jean Taris"), unlike the self-funded and therefore totally independent (a rarity then, as now) À Propos de Nice, was externally financed, commissioned by the giant Parisian film studio Gaumont as part of an omnibus-documentary project. He was therefore assigned his subject, the handsome and popular young French swimming champion Jean Taris. The 10-minute film was ordered to be a demonstration of swimming technique courtesy Taris, but in Vigo's hands, which were clearly itching with filmmaking fever, it becomes at least as much an example of cinematic form and technique. Vigo packs this little short with as many technical experimentations as he can get away with, employing Cocteau-like backward-running effects, underwater shots of Taris either in full form or just flirting with the camera, and some stately, very slow-motion footage of Taris just displacing water with his crawl stroke that, for sheer cinematic beauty, may not have met its match until Kubrick took the inspiration, expanded on it, and drew it out in A Clockwork Orange.

Despite its overtly, purely commercial origins, Taris is an utterly charming example of cinematic artistry at play. It shows Vigo training himself in much the same way Taris himself would prepare for a swimming competition (the underwater shots here clearly anticipate one of the most well-known bits of L'Atalante), getting all of his techniques down and well-rehearsed before moving on to the two definitive, classic longer works on which he would unexpectedly end his career.

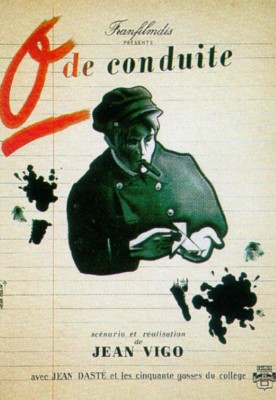

Zéro de conduite

Or, the history of a revolution, both story-wise and in the history of cinema. Vigo's first narrative work, running about 45 minutes, is a huge leap forward from his earlier shorts. It is as if his imagination was primed after having sought out and played with all the inventive techniques he employed in À Propos de Nice and Taris, and now he was ready to channel his excitement for the medium into a more personal, pointed statement.

Zéro de conduite's story is the perfect one to tell in the limitation-smashing, anti-repressive style Vigo was developing in his earlier work; not even in L'Atalante did he achieve such a profound, if surprisingly mischievous, unity of form and content. (This may be why some consider it, and not the less concise L'Atalante, his greatest and/or most representative work--a valid opinion with which I would respectfully disagree.) We open in the passenger compartment of a train that is speeding some junior high school-age boys away from their freedom and back to the soul-crushingly regimented boarding school where they spend most of the year. Riding along with them is M. Huguet (Jean Dasté, future star of L'Atalante), whom the boys, between their boredom-killing exchanges of pranks and tricks that only hint at their future rowdiness, and not knowing that they are to be his students, mockingly refer to as a corpse. He turns out not to be exactly that; with his penchant for veering off into impromptu Chaplin impersonations or just forgetting about his wards and letting them do as they please, he is the only adult even partly on their side in an administration of authoritarian and ridiculous teachers and headmasters (one of whom, the most senior, is a puffed-up, literally "little" person/dwarf with a high voice and a Napoleon complex). Once the boys arrive, they are lined up (in a shot whose framing and action recall nothing so much as the symmetrically militaristic opening of Full Metal Jacket) in what can only be referred to as their barracks, and dressed down by one of their sterner teachers, who gives out "zero for conduct, confined to school on Sunday" punishments rather too readily for the boys, whose freedom is so limited that a few Sunday hours out of school are their most precious commodity. Hence four of them--Caussat (Louis Lefebvre), Colin (Gilbert Pruchon), Bruel (Coco Golstein), and the younger, shy, sensitive, "sissy" but defiant Tabard (Gérard de Bédarieux)--are conspiring to revolt and overthrow the school's crusty old despots. The point of no return for their revolution-in-planning comes when the headmaster calls Tabard into his office and castigates him for his vaguely "too-close" relationship with Bruel (there was no word for "homophobia" in those days, but that is what the headmaster is perpetrating); the next time an instructor harasses little Tabard, he stands up and shouts in his face, "Je vous dis merde!" ("I say 'shit' to you!"). It's the first blow in an escalating revolution that finds all the classmates throwing off the shackles of their oppressors, mock-crucifying an instructor by tying him down and standing his bed up as he sleeps, and eventually breaking decisively free of petty authority by ruining the school's pompous yearly day of military-style pageantry.

Vigo and Kaufman make something surprising out of practically every scene in Zéro de conduite. A satirical drawing of one of the sterner teachers suddenly comes to animated life on the pad; the boys attack the school's stuffy, status quo-enforcing, militaristic annual "celebration" from the rooftops above, then gallivant about up there in a shot composed in such a way as to suggest that their horizons--the potential for their revolution's ascent--are limitless; and, in perhaps the film's most memorable moment, a triumphant parade of boys in nightshirts, pillow feathers raining down around them after a disruptive skirmish in their prison-like barracks, becomes a truly elegant, majestic spectacle through the aesthetically bold magic of slow motion. Vigo's first masterpiece is an ode to freedom and the flippancy of youth; it is timeless, but with its spirit of intelligent, passionate revolt and its casual narrative and stylistic disregard for the rules, it's also a punk-rock film forty years ahead of its time.

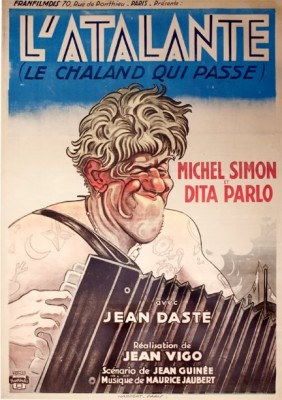

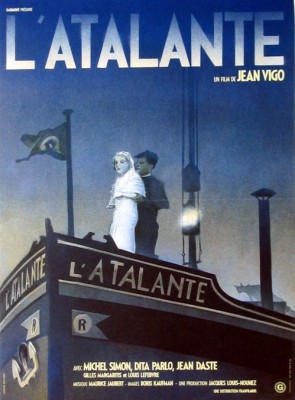

L'Atalante

"It is a nice, vulgar novel for a train journey, full of old-fashioned sentiments. But it is with this kind of novel that one can make the best films." - Jean-Luc Godard on adapting Alberto Moravia's novel for Le Mépris (Contempt).

To slip in that quote here is pertinent to all of Vigo's work, which had a profound effect on Godard that not only has he happily alluded to himself (using the most tender melodic excerpt from Maurice Jaubert's lovely L'Atalante score in In Praise of Love, for example), but which is visible in both the anarchistic spirit and, often, the physical form of his work (any of Vigo's films could have been called Breathless). But I was particularly reminded of it when watching 1934's L'Atalante, Vigo's final film and only feature, the basic scenario/script and story of which was found to be saccharine, throwaway, and "old-fashioned" by everyone involved, including Vigo, who then transformed it into one of the most beautiful, affecting, genuinely poetic, most beloved and admired films ever made, proving once and for all (if any further proof was ever needed) that script, plot, timelines--all the "narrative" elements--are only the blueprint from which a film is built, and even banalities on the script level can be transformed into great things during a film's actual construction.

L'Àtalante's story is that of a newlywed couple, bargeman Jean (Jean Dasté) and country girl Juliette (Dita Parlo), who face the typical challenges of being newly married while getting accustomed to one another and their life together on Jean's barge, "L'Àtalante." The film opens with a lyrical, only slightly melancholy-tinged aura of sunshine and optimism (the first of the film's many sparks flying from Vigo and Kaufman's unique admixture of their unpredictable open-air exteriors with the artifice of their cinematic process) as Jean and Juliette's country marriage ceremony has come to an end, and the wedding party is proceeding to the barge to see Juliette off in a bittersweet farewell. But wedded bliss is no permanent state, and although the couple is passionately in love, Jean's pragmatism (developed in his years of life on the river) and jealousy threaten to cramp the style of Juliette, who cannot wait to see Paris and be swept up in the romance of sights, sounds, and experiences her sheltered life has kept from her. Further complicating and enriching the little world of the barge is the presence of cranky, eccentric Père Jules (Michel Simon, the singular star of Renoir's Boudu Saved from Drowning, one of Vigo's inspirations) and his constantly growing brood of doted-upon cats, as well Jules's young, slightly dim sidekick (Louis Lefebvre). Narratively speaking, the film progresses as a series of conflicts, misunderstandings, and reconciliations, with Jean and Juliette, aided by Pére Jules's crusty wisdom and, in the end, his actual benevolent intervention, discover and learn to tolerate the sharper edges of each other's personalities. Thus the predictable happiness/threatened happiness/happiness regained romantic-comedy arc does not go unrespected.

But if Vigo and Kaufman do not exactly subvert the conventions of their story, they find a million deliriously pleasurable ways to make it come alive at every moment, and it is their singular melding of poetry and realism that has earned L'Atalante its ecstatic, even obsessive esteem and placed it high in the running for the most exemplary of all those great French works of "poetic realism" (e.g., Renoir's films of the period, Carné's Le Quai des brumes, Divivier's Pépé le Moko, all of which it predated) from the 1930s. If the wide-eyed kind of romanticism that could be tiresomely applied to the state of being newly wed is tamped down by Vigo, the sheer physical joy of it is played up; whenever I see the scene in which Jean and Juliette, asleep in separate beds, stretch and writhe in their respective places of repose with a suggestive restlessness and are then united in their nocturnal arousal through montage, I am reminded yet again of the surprisingly erotic uses to which Vigo could put his celluloid--a true, joyous celebration of physical sensuousness that is rare enough in our more graphic time, let alone in 1934.

In every other way, too, L'Atalante's aesthetic uniqueness is almost indescribable; Vigo and Kaufman never pass up an opportunity to heighten the film's power, using mise-en-scène and the photographic properties of their cinematic tools to open our eyes to the bits of magic that are always there in the world around us. That opening post-wedding scene is perceptibly in love with the spaces of the fields, the natural light and open air that creates the simple but unsurpassable glory of this sacred moment in the lives Jean and Juliette. Père Jules's little room, for another example, is shown to be a curio cabinet containing the strange trinkets of a lifetime's voyages to the most exotic locales. Juliette holds the folksy belief that if one opens one's eyes and gazes with enough purposeful intention when one's head is underwater, one catches a glimpse of one's beloved; Jean is a bit skeptical until, in the film's justly celebrated underwater sequence, it actually happens for him.

But these descriptions can only be a pallid indicator of how inexpressibly splendiferous is the experience that awaits you in this, the crowning jewel of Vigo's humanely, joyously, lovingly anarchistic body of work, the cruel brevity of which cannot overshadow its outrageously generous affection for human life and experience. The epiphany will only come once you have sought out The Complete Jean Vigo and treated yourself to your own viewing of it so that you, too, can be filled up beyond words by the powers of cinematic expressiveness that were Jean Vigo's alone.

THE BD:

Each of the films in The Complete Jean Vigo is presented at its correct aspect ratio: 1.33:1 for À propos de Nice and L'Àtalante, 1.19:1 for Taris and Zéro de conduite. The AVC/MPEG-4 transfers, mastered at 1080p, retain as much of the films' uniquely luminous texture as one could have hoped for; what were some fairly worn and beaten-up sources have been miraculously restored (as demonstrated in the Les Voyages de L'Atalante supplement reviewed below). As with many films as old as these, there may be no such thing as a pristine version available (or that, truthfully, was ever seen, even by original audiences); but all of Vigo's and Kaufman's visual flights--their striking compositions, framing, mise-en-scène, lighting, and camera movements--have truly been given the Criterion treatment and are done the fullest justice possible by these transfers, which represent yet another of those praiseworthy acts of film preservation that have earned the Criterion Collection its reputation.

Sound:With the exception of À propos de Nice, which was released as a silent and is here given a score by composer Marc Perrone, all of the films are presented with restored original sound on uncompressed PCM monaural soundtracks. Vigo was working at the very beginning of the sound era, and though these are bona fide "talkies," the original sound elements are occasionally rough (distortions and unpredictably varying levels are occasionally present, especially in the dialogue), as one would expect from a new and as yet unperfected technology. But it all comes through as fully and clearly as possible for films of this vintage, and it can be affirmed that, as usual, Criterion has done a thorough and conscientious job on the audio restoration.

Extras:--Michael Temple--a British film scholar, professor, and author of a book on Vigo--takes on the daunting task of giving an engaging, relevant commentary for each of the four films, and he accomplishes it with aplomb, focusing his expertise to give us maximum relevant details, anecdotes, history, and context regarding Vigo's life, politics, aesthetic, and filmmaking practices. Temple is effusive, but in the good way, remaining coherent and on-topic, sometimes digressing to offer an interesting tidbit or interrupting himself if he comes to an especially noteworthy scene or moment, but always basing his flights of enthusiasm in the film and blithely bringing us back around to where he left off.

--A Tribute by Michel Gondry: A cute 45-second bit of animation in which Gondry attempts to actually depict in direct, visual terms how Vigo got into his head and inspired him as a filmmaker.

--A 1964 episode, centered around Vigo, of the invaluable French TV series "Cinéastes de Notre Temps". The cornerstone of The Complete Jean Vigo's contextualizing supplements this 98-minute installment is really a full-fledged feature-length documentary on Vigo and his career, tracing both life and work in chronological order, liberally interspersing fascinating interviews with Vigo's collaborators (his benefactor/patron/protector Jean-Louis Nounez; assistant director Albert Riéra; actors Dita Parlo, Michel Simon, Jean Dasté, and Louis Lefebvre; even a childhood aquaintance on whose personality and even name a principal character in Zéro de conduite was based).

--"Truffaut and Rohmer on L'Atalante", an in-depth 20-minute interview with New Wave figurehead Rohmer (My Night at Maud's) posing most of the questions and François Truffaut (whose The 400 Blows is, along with Lindsay Anderson's If..., the most direct descendant of Zéro de conduite) giving most of the answers. This piece was prepared to air alongside a 1968 French TV broadcast of Vigo's films, and insofar as its aim is to introduce and explain Vigo to a TV audience new to his work, the interview is enlightening and accessible. Bringing together as it does three French film legends (Vigo, Rohmer, Truffaut), it's also pure catnip for cinephiles.

--Les Voyages de L'Atalante, a 40-minute visual essay from 2001 by film scholar/restorer Bernard Eisenschitz, who narrates over selected scenes, demonstrating and explicating the various versions of the film that have existed from its initial completion to its present-day, most fully restored iteration. This piece acts as an all-in-one restoration comparison (our glimpses of prior, blurry, scratched-up and threadbare prints reinforcing the amazing job Criterion has done with the transfer) and intricately detailed history of the film's evolution, from its disastrously mutilated 1934 cut to the hastily slashed producers' version (released as Le Chaland qui passe and replacing Jaubert's essential music with a popular tone) to the close-to-"original" version (as close as we are every likely to get) that Criterion has now brought to us.

--Otar Iosseliani on Vigo, a 20-minute video interview with the expatriate-Russian French filmmaker (Monday Morning) in which he struggles to find the words to express how deeply inspired he was by Vigo; he considers that he would never have become a filmmaker at all were it not for having seen L'Atalante. His recollections of having first seen this film surreptitiously in the Russian Film Archives as a student in the 1960s gives us some special insight into how daring his predecessor's vision was: Iosseliani was exposed to and transformed by Vigo's anything-goes ideology while living under the nothing-goes totalitarianism of the USSR of the time.

--A selection of extended scenes from Vigo's initial rough cut of À propos de Nice, some of which do further extend their beauty and imaginativeness, but which were later pared down by the filmmaker to give the work overall a more tightly constructed shape.

--A thick, splendidly designed (as always) booklet featuring essays on Vigo, from a variety of viewpoints and with multifarious emphases, from sources both expected (film writers Luc Sante, Robert Polito, and B. Kite) and not (filmmaker Michael Almereyda (Nadja).

FINAL THOUGHTS:How sad that, his life having been cut short at the height of his creativity, all of Jean Vigo's works fit neatly onto one Blu-ray disc; but how magnificent that such a disc now exists. Each of Vigo's films bears the indelible stamp of the strong, unfettered, poetically liberationist sensibility of its creator, a pioneer of the truly independent film. Though these films' stories and themes could have been recounted and dealt with cinematically in any number of ways, experiencing them makes it clear that only Vigo could have transformed them into these adroitly accomplished, painstakingly crafted, yet extraordinarily free works of art. If Vigo's contribution to the cinema has had a perennially vital influence that might seem well out of proportion to his sadly truncated filmography, it only takes an afternoon spent with these magical, authentic, rebelliously personal films to understand why. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||