| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Magic Trip

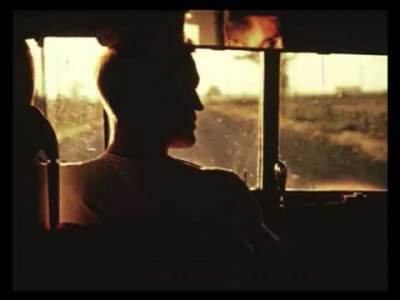

The 1964 cross-country hallucinogen-fueled road trip of authors Ken Kesey, Neal Cassady, and the so-called "Merry Pranksters" has been lionized seemingly since the moment it ended (if not before), but here's one lesser-known aspect of the trip: the group brought along a battery of film cameras, and shot pretty much everything that happened. Of course, none of them had the foggiest idea how the hell to make a film, so the audio tape recordings were wildly out of sync, and the mass of footage (30+ hours) would have been a daunting task for an experienced film editor, and there was not one to be found. Various parties tinkered with the footage for 40 years, and then gave up and put it away.

Filmmakers Alex Gibney and Allison Elwood have rescued that footage from oblivion, and it makes up the bulk of their new documentary on that journey, Magic Trip (subtitled "Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool Place"). Gibney, one of our most talented (and prolific) documentarians, mostly specializes in tales of contemporary politics, policy, and corruption (including Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, Casino Jack and the United States of Money, and Client 9). But he has an interest in the history of American counterculture, as evidenced by his 2008 Hunter S. Thompson bio-doc Gonzo. Ellwood was the editor of that film, and several of his others; she edits this one, and the pair shares writing and directing credits.

They place the Pranksters' trip in its proper historical context--we tend to forget that the early 1960s were basically more of the 1950s, and though the assassination of Kennedy the previous year is often acknowledged as a turning point for the country, Kesey's description of it as a personal, existential crisis for all Americans is less frequently articulated. The strangeness floating through the American ether, and his own experiences with LSD (the first of them being, he points out, as part of a government experiment), gave him the desire "to experience the American landscape, and heartscape." The filmmakers are also careful to make clear what an odd and radical act it was, this band of weirdos chugging across the country in a brightly-painted 1939 school bus. "People didn't think we were hippies or we were drug freaks," we're told, because "that wouldn't have occurred to them, because it wasn't in the news yet."

That treasure trove of footage from the trip provides the bulk of the film's visual elements, accompanied by interview recordings and readings of interview transcripts from pretty much everyone on board (Stanley Tucci provides opening narration and acts as an "interviewer" for the audio). Though the interviews are off-camera, the filmmakers provide frequent on-screen captions to remind us whose voice is whose; it may strike some as repetitious, but as the recent American: The Bill Hicks Story (which similarly kept its interview subjects off the screen) proved, it's easy to lose track of who's who when you don't have a face to put with a name.

The interviews themselves are somewhat problematic, in that the four participants whose interview transcripts are read mix uneasily with the actual interview recordings of others. A similar (if less bothersome) issue occurred in Gibney's Client 9, where Eliot Spitzer's most frequent escort would not appear on camera, so the filmmaker hired an actress to "perform" her interview. The trouble, in both cases, is that there is an unquestionable (if subtle) contrast between someone being interviewed, spontaneously answering questions, and even the finest actor reading dialogue. They just sound different, and here it becomes something of a distraction.

Strangely, some of the film's strongest sequences are its detours from the cross-country journey--a brief examination of Kesey's success with Cuckoo's Nest (and why he refused to endorse, or even see, the film version), a late sequence on the rise of LSD in the counter-culture and its often-comical appearances in the square mainstream (those drug propaganda films and Dragnet clips are always good for a laugh), and what may very well be the film's best scene, a clever, stylish reenactment of Kesey's first trip. Utilizing audio tapes of his reactions, captioned by bold text and illustrated by tight close-ups (ticking clocks, burning light bulbs) that slowly give way to bright colors and animation, it's an inventive, funny (and seemingly authentic) sequence, as entertaining as it is daring.

By the time the Pranksters arrived at the New York World's Fair, their ostensible target, it could only disappoint--"The trip became more important than the destination," Kesey muses, which became somewhat true of the entire movement. But they carry on, coming back across the country, their post-trip screenings morphing into the notorious roaming "Acid Tests," but by this point, the viewer's attention has begun to flag a bit--the film is weakened by its flabby length and too-worshipful point-of-view towards its subjects. Gibney's best work has an immediacy that it is not solely the byproduct of the contemporary subject matter; though Magic Trip has some great footage and funny stories, and the topic is approached with enthusiasm and an anthropologist's disposition, it lacks a certain force and power that we've come to expect from the filmmaker. There's a tantalizing glimpse of it, late in the film, in Kesey's memory of the signs warning visitors of Yellowstone about the bears--a notion that segues into his commentary on how fear had begun to take over American life. It's a notion that is awfully resonant at this very moment in our discourse. But there are too few analogous moments like that. For the most part, the journey of Kesey and his friends is seen in much the same way as the close-ups of the dilapidated bus that close the film: as an old thing, ancient history.

Jason lives in New York. He holds an MA in Cultural Reporting and Criticism from NYU.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||