| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Sophia Loren: Award Collection

The title of this set should properly be The Sophia Loren/Vittorio de Sica Collection, as all of the films collected therein are collaborations between the ripe and ravishing young starlet and the grand old man of Italian cinema, the most softhearted (some might say sentimental) of the '40s Neorealists, who had exposed with compassion and humor the intimately felt postwar economic ills of his country and drawn many a tear along the way with such beloved masterworks as Bicycle Thieves and Shoeshine. In his '60s work featuring Loren (including the great Two Women, in a category if its own and not included here), de Sica extended his class-conscious, generously humanistic worldview while incorporating the sexier, more ebullient (and certainly more colorful) cultural outlook of the time. It is indicative of their author's sensibility that he chose scripts that always allow Loren to play a member of Italy's working underclass, her character more often than not a barely literate prostitute whom we are asked not to pity or judge but whose brave independence and pragmatism in the face of overwhelming challenges we are encouraged to admire. In Loren, De Sica found a new, erotic embodiment of the neglected working-class Italian majority to whom he never tired of paying tribute and whose vitality, ingenuity, and toughness he had an abiding, warm affection toward--an affection he continued to pass on to international movie audiences through these later, perhaps lighter and funnier, but no less moving works.

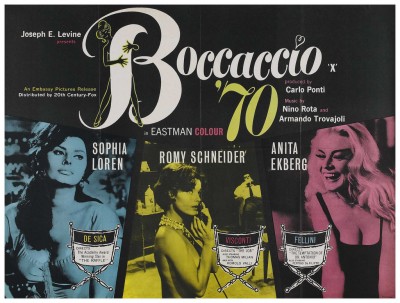

Boccaccio '70

The boxed set begins at the point where de Sica and Loren literally have their rendez-vous with the Italian cinema of the time. Theirs is the closing segment of this omnibus film conceived by Italian mega-producer Carlo Ponti (who was married to Loren and also oversaw the other films in the set), which comprises four mini-features by the superstar Italian directors of the day: Mario Monicelli (Big Deal on Madonna Street), Federico Fellini (La Dolce Vita), Luchino Visconti (Senso), and de Sica--that together aim, as the trailer puts it, to offer the kinds of enticing tales that the medieval Italian author of The Decameron might have spun for audiences circa 1970. (This despite the film's having been made in 1962; while not exactly avant-garde in content, the film is literally ahead of its time.) Unlike Boccaccio's interconnected stories, however, these films are presented as discrete "acts," each with its own credits, separated by the appearance of a stage curtain onscreen.

Monicelli's segment, "Renzo and Lucian," is the story of a pair of coworkers, Renzo (Germano Gilioli) and Luciana (Maria Solinas), who work at a biscuit factory where the employees are gender-segregated and dating and marriage among them are forbidden. The couple defies the rules and gets married on the sly, but they are also too poor to afford their own place, and they have to live with Luciana's family in their crowded apartment. The charade they have to keep up around their coworkers, the total lack of the privacy desperately craved by any couple in the honeymoon phase, and Marisa's relentless economizing to save for the petit-bourgeois future she envisions for herself and Renzo (complete with appliances!) are all played for laughs, but there is a melancholic undercurrent. The love story plays out in the ultra-modern factory and in Italy's new-construction suburbs--all petrol stations, uniform architecture, and advertisements. As evoked by Monicelli and his DP, Armando Nannuzzi (The Damned), the world that surrounds Renzo and Luciana and provides the backdrop for their romance, amusing trials, and misunderstandings strongly resembles the postindustrial ennui-scape shown to us by Antonioni in Red Desert; in this context, the couple's materialistically fulfilled "happy" ending, however lightheartedly presented, is punctuated with a huge question mark.

Fellini's section, "The Temptation of Dr. Antonio," (his first color film!) is the most exclusively comedic of the bunch, and it is truly hysterical, with Fellini capitalizing on the then quite current hype and scandal (especially in Catholic Italy) over his irreverent films and their cheerfully frank sexuality, all epitomized by the lusciously curvaceous Anita Ekberg, who famously got herself all wet while playing in a public fountain in the Fellini film preceding this one, La Dolce Vita. Dr. Antonio (the wonderfully physical comedian Peppino de Filippo), a crusading prude who lives with his sister and frets obsessively over the decline of public morals, is appalled to see a gigantic billboard featuring the busty, sensually reclining Ekberg caressing a glass of milk (the product being advertised). His state goes from aghast to frenzied to absolutely apoplectic as he becomes more and more insanely focused on this giant representation of this gorgeous woman. Ekberg's image seems to taunt him, and something finally snaps, after which the film evolves into Fellini's own rendition of The Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman as Ekberg comes to (larger than) life and rampages like some uncannily sexy King Kong, chasing down poor Dr. Antonio to grill him about his public attacks on her morals-loosening allure and to save him from his own prudishness with a healthy dose of earthly passion. This all unfolds in an actually very innocuous, with Otello Martelli's sunny cinematography and Nino Rota's zany score adding the lightest of touches. The laughs come fast and furious, and the film is the most relaxed and charming of the bunch; our voice-over narrator is a benevolently naughty little Cupid who winks us off toward the next episode as this one closes, and Ekberg's milk billboard is accompanied by a Rota-composed jingle, sung by urchins admonishing us over and over in no uncertain terms to "drink more milk!", whose grating melody is so catchy that the tune then becomes your mental soundtrack for the remainder of Boccaccio '70, since you will never, ever be able to get it out of your head.

Visconti's portion, "Il Lavoro" ("The Job") addresses a theme characteristic of the director, who was aristocratic by birth and Communist by political orientation: the ambivalent decline, both material and spiritual, of Italy's aristocratic class. Here, that decline presents itself in the form of the failing marriage of penniless Count Ottavio (Tomas Milian) to wealthy non-aristocrat's daughter Pupe (Romy Schneider). Count Ottavio has gathered his lawyers around him to see what to do about all the tabloid stories tattling on him and his many extramarital flings; meanwhile, the hapless Pupe gets home in a surprisingly good mood and calls him in for a private conference to announce she's divorcing him and finding a job so that she, who has never worked a day in her life (and it shows, for both better and worse), can see and experience how real people live. The ensuing conversation, which constitutes the bulk of the film, sees the layers of glib, cynical, anti-romantic, money-is-everything upper-crust cool slowly peeled away to reveal the vulnerability, hurt, and uncertainty of these two individuals who may or may not care for each other, but who are both victims of a system (of thinking, of society) that has virtually forced them into the hypocrisy that compromises and traps them, robbing them of a chance to stand back and decide their own path through love and life. This is another of Visconti's almost musically conceived, tragic melodramas, and if its swooning heightened-reality artifice jars somewhat when set against its bawdier, lustier, zestier Boccaccio '70 compatriots, it immerses us in itself at least for the duration of time that Milian and Schneider are onscreen, experiencing their glamorous but doomed fate against a burnished, colorful boudoir setting--with Schneider looking every inch the smart young starlet--evoked with eye-ravishing attention to shade and detail by production designer Mario Garbuglia and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno.

Which leads us to de Sica's "The Raffle," his reunification with Sophia Loren after their critical and box-office smash Two Women. This one combines the virtues of the preceding Fellini installment (humor) with those of the Visconti entry (tragedy) as it follows the fate of a tough-cookie carnival-game barker, Zoe (Loren), who is causing great excitement and raising some much-needed income for her struggling, tax-owing, pregnant sister (who owns their booth) by being the "prize" in a raffle for which the tickets are very limited and very high-priced. Matters are complicated by a handsome young de facto toreador, Gaetano (Luigi Giuliani), who saves her from a bull that, like the men always gathered around her, is driven crazy by her shape-fitting red dress. Zoe is no starry-eyed romantic; she is a realist absolutely committed to her family's well-being, and when it comes to the leering men and the raffle, she is experienced and thick-skinned enough to handle it. But she truly seems to be falling in love with Gaetano, who offers her something she seems to have rarely experienced: love unfettered by financial obligation. If it is amusing to see what fools the sassy, wisecracking Loren turns men into, it is heartbreaking to see her struggle between rescuing her family from the predatory tax collector and her one chance at a true love she is not sure she deserves. "The Raffle" is, aesthetically speaking, the loosest (you could even say rawest) of the bunch. While it is certainly just as colorful and confident as the others, there is a down-in-the streets feel deriving from the real, raucous, fairground-like milieu in which de Sica has set the piece, casting nonprofessional actors for added verisimilitude as was his habit, that harks back to his Neoralist roots. "The Raffle" thus makes the perfect gateway to the rest of the Sophia Loren Award Collection set, acting as a jumping-off point from which star and director branch out to explore new tones and shadings in an ongoing, well-suited collaboration.

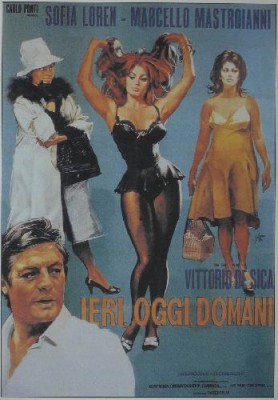

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

The year following Boccaccio '70, de Sica put Loren in a film that is, in a way, the inverse of what "The Raffle" was for her and her director, their portion of that film having been just one part of a larger project. Here, de Sica's is the controlling vision throughout, while Loren plays three different roles in the film's triptych of "short stories," each with a different kind of woman at the center (each of whom is romantically involved with Marcello Mastroianni, himself playing three different characters), which in its form recalls Ophuls's Le Plaisir.In the film's first, longest part, "Adelina," Loren is the petty criminal of the title, who sells black-market cigarettes and supports her perennially jobless but loving husband, Carmine (Mastroianni). When she is threatened with arrest, she discovers a loophole in the law concerning women in her line of work: pregnant and nursing perpetrators are granted full amnesty. Thus begins the nonstop parade of pregnancy, birth, and nursing that grows the family to the bursting point of their tiny, cramped apartment while keeping Adelina safely out of jail. But can Carmine and Adelina's love survive the rock-and-a-hard-place existence between the lack of sleep and romance guaranteed by their expanding brood on the one hand, and on the other the arrest and imprisonment of Adelina?

In the middle part, "Anna," Loren is a dissatisfied, bored upper-class wife looking for some dangerous Lady Chatterley-like love with a struggling writer, Renzo (Mastroianni). Her scattered, frivolous, sometimes horrendously, hilariously selfish voice-over thoughts punctuate the soundtrack as she drives harriedly around the city, until she picks up Renzo for a drive to the countryside. During their conversation (the drive is brilliantly edited in a way that never allows a dull moment in this segment's single location/setting and real-time pace), Anna reveals her true nature, and Renzo begins to doubt her ability to be anything but a materialistic, grasping, self-centered trophy wife. When a sudden crisis puts their journey to an abrupt end, Renzo is abandoned, but he is not angry; we can see on his face that it is the always-to-be-pampered, never-to-be-loved Anna that he, and we, should feel sorry for.

Finally, in the gently bawdy "Mara," a penthouse-dwelling call girl (Loren, natch) becomes the unwitting object of affection for both her marriage-minded number-one client, Augusto (Mastroianni) and a young man in the adjoining rooftop apartment (Aramando Trovajoli), who lives with his grandparents and is a novitiate waiting to become a priest. Mara is drawn to the young man's innocent, naive handsomeness; he is attracted to her for the obvious reasons, but also for her own genuine sweetness. When his understandably disapproving grandmother implores Mara to do something about the future her grandson is about to throw away for his romantic attachment to the nice hooker next door, however, Mara feels guilty and recruits the unwilling help of Augusto to show the young man that his fate must necessarily lead him elsewhere for his own good and happiness. But what will their collaboration on this venture mean for the all-business Mara and the head-over-heels Augusto?

There seems to be little connection between the film's three segments, but this is of no great importance considering how successful each part is on its own. The cityscape of Naples is what unites all the stories, and de Sica uses Giuseppe Rotunno's lush Technicolor cinematography to evoke its different facets (most strikingly the fog of a rural highway in the "Anna" portion) as each of the Lorens and Mastroiannis live out their humorous, humanely observed adventures in its various milieus.

Marriage Italian Style

Oddly, what is arguably the most famous film of the set is also the weakest. Not that Marriage Italian Style does not hold some interest--most of which comes from the enduring chemistry between Loren and Mastroianni--but de Sica seems less engaged with this material than he does with that of the other films, and as the film's plot keeps growing more and more absurdly complicated, its shifts in tone and constant-flashback structure come to seem more and more tiresome. Loren plays Filumena, who senses true love when Domenico Soriano (Mastroianni) comes to her aid when she is an employee and he a client at a brothel during a WWII air raid. Their paths keep crossing over the years, and he eventually gives her a part in his life, but he is stubbornly reticent about marriage and hypocritical about the role a woman he has already slept with (and who has, obviously, slept with others) can play in the life of a well-off, upstanding citizen from a good family such as himself. Filumena, grateful at first but then feeling slighted and used, finally, after decades of serving as his right-hand man in business and servant-girl/mistress at home (where he tries to hide the true nature of their relationship from everyone, especially his mother), comes up with a scheme to ensnare Domenico's hand in marriage. It is a marriage not exactly made in heaven, and it turns out that her reasons for trapping Domenico extend to a past and a part of her life--revealed to us once more in flashback--that he has had no idea of until now. A happy ending seems impossible, but the stakes are high and keep getting higher as the film goes on, and Filumena is very, very determined....

As the characters age, and as their stories keep getting tied into more and more tangled knots, one turn of events after another transpires, and something calcifies in Marriage Italian Style; after a certain point, it just plows forward with a decreasing supply of inspiration. The film begins with an assured and invested-enough approach, but its second half seems to drag even as the script (co-written by a gang that includes the great Tonino Guerra--too many chefs, as they say) convolutes motivations and piles coincidences and plot twists one on top of the other, steering the film heads irretrievably into some trickily artificial territory that would have needed more elegance to be melodrama or a lighter touch to work as romantic comedy. The saving grace really is Loren and Mastroianni; their characters may devolve into inscrutably overcomplicated figures whose ultimate fates we care less and less about, but their joint presence is always enjoyable, adding a spark to even the most ho-hum stretches of the film.

Sunflower

De Sica takes Loren and Mastroianni back to the World War II era, where Marriage Italian Style started out, but this time with markedly more success. Loren is Giovanna, a peasant girl who falls in love with Antonio (Mastroianni), who is about to be taken away from her and his civilian life forever as a conscript in Mussolini's army, which is heading off on its doomed campaign on the Russian front. Despite their increasingly bold and desperate efforts to keep Antonio out of the army, they finally snare him, and Giovanna waits as the war winds to an end and the casualties mount, with never a word from Antonio. This situation continues even after any surviving soldiers have returned home, but in the absence of definite confirmation of his death, Giovanna keeps her hope alive that Antonio is still somehow trying to make his way back to her. When she finds out from a returned army comrade of Antonio's what region of the USSR he may have been left for dead in, Giovanna heads off to Russia to track him down, but what she finds instead leads her only to the startling, painful, and sobering realization that love stories like the one she and Antonio had been in the midst of are frighteningly vulnerable to being intruded upon and given a tragic ending by the heartless, violent exigencies of history and international politics.

Sunflower is the prettiest-looking of The Sophia Loren Award Set's offerings, with de Sica going back to his Neorealist roots in the most forthright way we ever see in this group of films, taking cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno onto the streets of Moscow and into the fields of Italy and Russia for authentic location shooting while also utilizing the film's color, vast geographical range, and Loren's and Mastroianni's now more mature visages to make Sunflower's melodrama work in a way that that of Marriage Italian Style never quite did. The film's final, outrageously but sublimely tear-jerking moments are fully controlled in tone, as is the film in general; they could have been a blueprint for the ending, quite similar in form and content, of Todd Haynes's Far from Heaven, as both depict, in a way that both quickens and breaks the heart, the inexorable separation of two strong but not invulnerable people at the hands of social, political, and historical forces bigger and more powerful than they are.

THE BD:

Each of the films is presented in anamorphic widescreen at its original aspect ratio (all 1.85:1 with the exception of 2.35:1 'scope for Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow), with AVC/MPEG-4 codec, 1080p-mastered transfers. Boccacio '70 and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow look great; there is barely a glitch in their bold, vibrant colorfulness. Strangely, since they were made somewhat later than the other two, Sunflower and, especially, Marriage, Italian Style suffer more from visual flaws; the latter has flickering on and off throughout and a patchy instability to its coloring (perhaps due to its particular colorization process; those matters could be rough and quite variable from lab to lab and process to process), while the former has occasional but noticeable pops and blips onscreen which indicate that the print could have used a bit more clean-up. Nothing on the visual level is nearly bad enough to be a deal-breaker at any point, though, and the visual quality over the course of the set works out to above-average.

Sound:As standard for Italian films of their eras, each film's DTS 1.0 mono soundtrack is post-dubbed in Italian (with well-made and -translated English subtitles). The sound is lovely for the most part: bold, clear, and fully dimensional, with no distortion. The only exception is Sunflower, which suffers from some tinniness and distortion in parts (especially noticeable on occasion at the level of Henry Mancini's music, for which he won an Oscar), but the sound is certainly passable and seems subpar mainly in comparison to the superb sound of the other films. As with the video, there are exceptions to the generally high quality, but the sound overall comes out to above-average.

Extras:Each disc contains theatrical trailers for the other films in the set (Sunflower has the previews for Boccaccio '70, Marriage, Italian Style, and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, for example) and stills galleries of varying detail (Boccaccio '70's stills include an international poster gallery in addition to photos from the film itself). The Marriage, Italian Style disc includes an additional promotional clip that is a hybrid trailer/person-on-the-street interview montage gauging the public's admiring reaction to and thoughts on Italian household names Mastroianni and Loren.

The biggest, most meaningful extra here is the additional DVD bonus that supplements the Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Blu-ray package: Mario Canale and Annarosi Mori's celebratory but honest 2009 feature-length documentary on de Sica, Vittorio D. Canale and Mori merge footage of the master at work and in public reflection on his career with interview footage of his children and those who admired, worked with, and learned from him, all of whom speak admiringly of his qualities and forgivingly of his flaws. (He had two families with his wife and mistress; he was an incorrigible and reckless gambling addict). Interviewees include actors Shirley Maclaine, Clint Eastwood, and Sophia Loren; Nobel prizewinning writer Dario Fo; legendary screenwriter Tonino Guerra; and a parade of venerating filmmakers including John Landis, Mario Monicelli, Woody Allen, Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, Federico Fellini, Paul Mazursky, and Abdellatif Kechiche (The Secret of the Grain).

FINAL THOUGHTS:Compiling four films that represent not only the iconic collaboration of Sophia Loren and Vittorio de Sica, but an entire era in Italian culture as it was experienced throughout the world through celluloid exports, The Sophia Loren Award Collection is a treasure chest that brings together the sexy Loren, the moving Loren, and the vivacious Loren in one box that is nothing less than a cornucopia of cinematic delights. All the treasures in this chest (pun intended) may not be of precisely equal value, but they are all worthwhile in their own way--some as very gratifying rediscoveries, some as minor pleasures, some as unexpected newfound delights (I, for one, had never heard much about Sunflower until its release here)--and Kino Lorber has polished them up rather nicely for our delectation. I would "recommend" Marriage, Italian Style and Sunflower and "highly recommend" Boccaccio '70 and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, but these films as a group play off each other very well, and are together Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||