| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Rules of the Game: The Criterion Collection, The

Please Note: The screen captures used here are taken from the 2004 DVD release, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

"The horrible thing about life is this: Everyone has their reasons."

A tragicomic masterpiece and an all-around great, inventive, sparkling, deservedly revered movie, Jean Renoir's The Rules of the Game (La Règle du jeu) (released in 1939) is the last, most powerful gasp of France's great cinematic tradition of poetic realism before World War II and German occupation put that humanistic tendency to a premature death. Even before the war, however, the film was violently rejected by its target audience, the Parisian bourgeoisie, who responded defensively to the film's satirizing of their hypocrisy, complacency, and decadence. That reaction seems misguided and disproportionate now, not just because the film is so imaginatively conceived and brilliantly, energetically executed as to warrant at least the grudging admiration of the class whose flaws it irreverently points up, but also because Renoir's satire is never vicious. It is quite the opposite, in fact, and the film could only be construed as an attack by the most paranoid and hypersensitive; its overarching triumph is its genuine, unsentimental kindness, extended equally to all its characters, who are never less than complicatedly human and whose "reasons" are acknowledged to stem from the same recognizable human vulnerability and needs we all share, even if some of them do passively belong and adhere to a social class on the wane because it's stifling in its own self-regard and self-indulgence.

The film opens, significantly, on the return back to earth of Lindbergh-like aviator André Jurieu (Roland Toutain), who has just landed after successfully completing a daring transatlantic flight and is greeted by crowds, photographers, and radio interviewers--everyone but the one person he needed to be there, Christine de La Chesnaye (Nora Grégor), with whom André is in love despite her being the wife of an aristocratic marquis (Marcel Dalio). Christine knows exactly who André is denouncing over the radio as a disappointing, infelicitous, heartbreaking woman as she listens in from her posh Paris apartment, so she has her chambermaid, Lisette (Paulette Dubost) switch it off; she wants no further confusion added to her inability to decide between her husband and her ardent admirer. She reassures the marquis that despite the more or less open, casual affairs on both of their parts, she truly loves him, and at least their relationship is built on clear-eyed openness and honesty. This, along with the very openly broadcast affection Jurieu feels for his wife, is taken as a wake-up call by the marquis, who resolves to be actually open and honest with (and, not least, faithful to) his trusting wife from this moment on, to the consternation of his mistress, Geneviève (Mila Parély). Meanwhile, André confides his all-consuming, near-suicidal passion for Christine to his and the de La Chesnayes' mutual friend, the avuncular Octave (played by Renoir himself), who, out of concern for André, convinces Christine to invite him along on the getaway she has been planning for a large upper-crust group at her and her husband's rural chateau.

The film's second half thus plays out in the country (exquisitely photographed by Renoir's cinematographer, Jean Bachelet, whose lighting and composition throughout are extremely fine) on Christine and her husband's expansive estate, where Jurieu, Christine and the marquis, Octave, and Geneviève are among the guests going out on shooting parties during the days and throwing fetes in the evenings, and where the elite set's haphazard, lackadaisical, affected nonchalance and disregard for matters of the heart is picked up on by the help. Lisette--who has already proudly announced her emulation of Christine's mores to the lady herself, breezily confessing her extramarital lovers--becomes the hotly, violently contested pinnacle of a love triangle whose other points are occupied by her husband, the gamekeeper Schumacher (Gaston Modot) and his enemy, Marceau (Julien Carette), a poacher whom the marquis has hired on to the chateau's staff out of his newfound sense of goodness and benevolence. Misunderstandings, heartache, quasi-slapstick drunken chaos, and, in the end, tragedy ensue as each character, whether socially high or low, has their real feelings and longings confused by the stale, "sophisticated" libertinism of their time and place--a libertinism that is experienced by them less as truly liberating and more as a subtle and inscrutable set of imposed "rules" by which the "game" of love and human relationships must be played.

All this projecting and refracting of emotion and desire from one partner to the next is hardly played out as just a frolicsome game of musical beds, however much charm and humor the film may have to spare; nor is the film only a satire of its group of spoiled, self-indulgent, irresponsible aristocrats and their hangers-on. Renoir is clearly dubious of the decaying, unsustainably isolated and privileged existences of the sort of haute-bourgeoisie people with which he's populated his film, but he cannot find it in him to condemn them as people; not a one of them has feelings we can't understand, however selfish, hurtful, or destructive they might be. Instead, there is a powerful melancholy, latent from the film's first moments, deriving from how frequently we human beings find our understandable needs, our "reasons," at cross-purposes. Renoir draws this melancholy out of all the gaiety, comedy, and high living so gradually that we never feel the shift, and by the time we reach the film's rather dark, sober ending, it seems entirely organic, just perfectly of a piece with what's come before.

Renoir's graceful, open-minded, open-hearted fluidity and freedom is expressed through the film's story by its avoidance of facile judgment and refusal to make any one floundering, morally disoriented, love-blinded character any more laughable or foolish than any of the others. It's there in his style, as well, both within the film's sequences as he seems to spontaneously locate and move the camera to capture perfectly all the steps in the dance of nature and life, and in its overall structure, organized to feel loose and roving as it gives each character center stage before moving on to the next one, connecting them as the stuff of life--passion, love, friendship, jealousy, resentment, misunderstanding--is passed from one to the other, somehow making them all equal links in the chain of humanity, a chain one hopes will survive the dying off, implied in the film's conclusion, of a dazzling but artificial and cruel way of organizing society as a rigid, faux-liberated hierarchy.

It is almost miraculous, the way Renoir is able to humanize all of his characters; surely, a part of the film's enduring appeal and greatness is that it's rare, in any kind of dramatic storytelling, for the tensions to play out with such equitability, and we are never called upon to dislike or look down on any of his people, even if they may themselves occasionally succumb to the nefarious impulse to look down upon and dislike each other. It is because The Rules of the Game has no heroes or villains, just lost, longing characters who are shown to be capable of both heroic and villainous behavior, that it is so trenchantly sad and sweet even when one considers the tartness of its depiction of widespread amorality. It's a technically very accomplished, gorgeous-looking, fantastically played movie, but its most salient quality is its superlative generosity, an empathy that the humanistic Renoir clearly sees as everyone's right. That belief is put into exemplary practice in all of his best work (e.g., the just about equally great The Grand Illusion), but with The Rules of the Game, it reaches its most remarkable, compelling, convincing, and inspiring peak. A work of art has no obligation, of course, to express morality or humanism in order to be great. But with this film, Renoir manages to be, simultaneously, a great artist and a great restorer of faith in humanity's better qualities.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The Rules of the Game is a film, rescued from the snapping jaws of history, that had its original source materials destroyed during World War II and has been reconstructed from available prints and other found bits and pieces. Despite the evident wear in some sections, however, the film remains quite intact, and its beauty is easily discernible through the intermittent lines, scratches, and slight graininess and flickering of the picture. This AVC/MPEG-4, 1080p, 1.33:1 aspect-ratio transfer is both a painstaking work of art unto itself--in which everything has been meticulously restored to look the best it possibly can despite some irreversible flaws in the available sources--and an important act of film preservation.

Sound:As helpfully noted by actress Mila Parély in her interview (see below), pre-war sound was endemically prone to distortion, and this is borne out by the film's sound, rather gritty and tinny by today's standards. Still, there is no evidence that Criterion has not done the best, most thorough sound polish possible for the disc's uncompressed PCM monaural soundtrack (in French with optional English subtitles), and there is the prevailing sense that one is definitely hearing the film as it "really" sounds, flaws and all.

Extras:The Rules of the Game received the full Criterion Collection treatment for their 2004 DVD release, and that extravaganza of extras has been retained in its entirety for the transition to Blu-ray:

--An audio commentary written by Renoir scholar (and friend of the great auteur during his later life) Alexander Sesonske and read by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show) in which Sesonske works, for the most part, at the appropriate overlapping point where the technical, historical, biographical, and storytelling aspects of the film and its production meet. If Sesonske leans a bit too heavily on exegesis--the explanation and interpretation of characters, story, and events--at the expense of breadth, it doesn't really render the commentary any less engaged, interesting, and insightful.

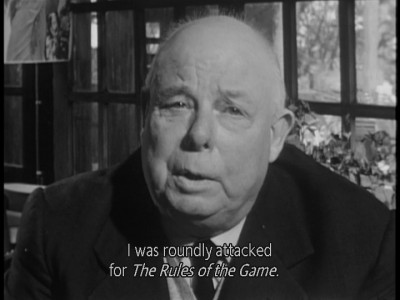

--An introduction by Jean Renoir (one of a series of introductions to his films he shot in the '60s) in which the grand old man of cinema spends seven or eight minutes discussing, in his charming, lively, self-deprecating but supremely intelligent way, his feelings for The Rules of the Game, his greatest film, his despondency when it was roundly rejected upon its release, and his sense of vindication and gratitude upon its later rediscovery and veneration.

--"Playing by Different Rules,", film historian Chris Faulkner's comparison of the film's original, 94-minute version with the 106-minute version we've had since 1959, when film club organizers Jean Gaborit and Jacques Durand reconstructed the film's long-lost, scattered pieces. The side-by-side version comparison, with Faulkner's narration, informs us about the immense change to the film's tone--harsher and more satirical in its shorter version; more complex, humane, and generous in Gaborit and Durand's version--effected by the '59 reconstruction. The short version ending is also included in its entirety.

--Two scene analyses, with close, incisive, and knowledgeable voice-over by Faulkner exploring, on the microcosmic level, the film's brilliance of technique, boldness of style, and confident, almost imperceptible coupling of its story and philosophical viewpoint(s).

--"La Règle et l'éxception", the relevant installment of Jean Renoir, le patron, a three-part 1966 episode of the French TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, in which Renoir sits for an impassioned yet convivial on-camera Q&A with renowned New Wave filmmaker Jacques Rivette (Va Savoir) and producer André Labarthe.

--The hour-long first part of film scholar David Thompson's 1995 BBC documentary Jean Renoir, which follows, in some detail, Renoir's life, from his birth in 1894 to his departure for Hollywood after The Rules of the Games's failure and the Nazi invasion of France, and includes interviews with such Renoir admirers and successors as Bogdanovich, Louis Malle (Au Revoir, les enfants), and Bernardo Bertolucci (The Last Emperor).

A section of supplements on the film's production history features a knowledgeable video essay/recap by Faulkner introducing us to the basics of the story behind the film's challenging production; a half-hour interview with French film scholar Olivier Curchod that goes into further, more opinionated detail; and a 10-minute interview from 1965, conducted for French television, in which the film's reconstructors, Jean Gaboit and Jacques Durand, recount the long, arduous, obsessive adventure of putting a virtually lost film back together again.

--A selection of interviews includes contemporary discussions with the film's production designer, Max Douy; one of its lead actresses, Mila Parély (who plays Geneviève in the film); and Renoir's son, Alain, who worked with his father on many films, including The Rules of the Game. Each of these conversations is rich with anecdotes confirming Renoir's affability, creativity, and even occasional vulnerability.

--Finally, a thick, wonderfully designed 40-page booklet contains an essay on the film by Sesonske; two pieces by Renoir himself (one a preliminary synopsis of the script, the other an excerpted recollection on making the film from his 1974 autobiography); a reminiscence by legendary photographer (and assistant director on Rules of the Game) Henri Cartier-Bresson; a two-age tribute apiece from Renoir's successors François Truffaut (Jules and Jim) and Bertrand Tavernier (Coup de torchon), and briefer words of praise by notables ranging from critics Robin Wood and J. Hoberman to filmmakers Paul Schrader (Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters) and Wim Wenders (Wings of Desire).

FINAL THOUGHTS:Radical in its free-spiritedness and masterful appearance of elegant simplicity, The Rules of the Game is actually incredibly well-wrought and complex, revealing yet more stylistic and technical grace notes and further deeply-explored dimensions in its characters every time one revisits it (a practice that this excellently-made Blu-ray edition makes an even more tempting and likely proposition). Like Citizen Kane, its American counterpart in the most-cited-as-best-film-ever-made sweepstakes, Jean Renoir's masterpiece is a gift that can be unwrapped over and over again, offering up fresh pleasures and provocations and feeling like a new discovery each and every time. This deluxe and delightful Criterion Collection release of the film is the definitive home-media version (at least for the foreseeable future) of a film whose towering-classic status is fully warranted, and it is therefore an unqualified must-have for all cinephiles. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||