| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Incendiary: The Willingham Case

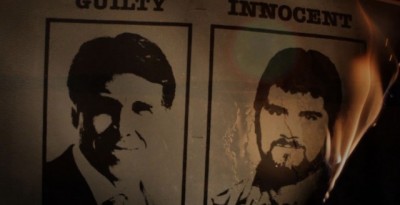

On the morning of December 23, 1991, the three children of Cameron Todd Willingham and his wife Stacy were killed in a blaze in their Texas home. Todd Willingham escaped from the fire, and was later convicted of their murder. He was sentenced to death, and in 2004, days before his execution, a report made its way to Governor Rick Perry that persuasively questioned the scientific veracity of the conclusion that the entire cast rested upon: that the fire in the Willingham home was arson. Governor Perry saw nothing of interest in the report, so the state went ahead and executed him. A few years later, in the wake of a scandal in the Houston Police's crime lab, the new Texas Forensic Science Commission decided to take another look at the scientific evaluation of the Willingham case. Two days before a review meeting of the report they commissioned, Perry replaced three members of that commission, including its chairman.

These are the facts conveyed by Incendiary: The Willingham Case, an upsetting, difficult, and mostly one-sided examination of the Willingham conviction, execution, and follow-up investigation. Let's be clear here: this is a work of advocacy. The filmmakers clearly feel that Willingham was wrongly accused, wrongly convicted, and wrongly executed--and that the subsequent maneuvers by Governor Perry were an attempt to cover up his mistake. We are told, from the first, pre-title interview with arson expert John Lentini, that "there's no evidence that he really did it. It's all fabrications and folklore."

The film then proceeds to present the undisputed facts of the girls' deaths, but also to make a case for Willingham's innocence--and does so in a convincing and riveting manner (and with a refusal to dumb down the considerable jargon and complicated science of his defenders). Directors Joe Bailey Jr. and Steve Mims do allow some counter-argument of Willingham's guilt--by his defense attorney, no less, though he's not presented as a terribly persuasive source ("It's common sense, part of it," he declares. "It's not rocket science!"). But they make the case for his innocence first, and that is often the point of view that sticks, as we all well know. Everything we find out after that is defensive information.

Is this dishonest, or unbalanced, or whatever? Maybe. Do we care? Not really, for two reasons. First, the story of the innocent man wrongfully accused is the interesting one, cinematically; in not only its narrative but its stylish execution, Incendiary is something like a Thin Blue Line, another tale of a wrongfully-convicted man on Texas's death row, but with a less happy ending. (The films even share a secondary villain: Dr. James Grigson, the court psychologist nicknamed "Dr. Death" for his assurance, time and again, that every defendant was a raging psychopath who would surely kill again. Dr. Grigson gave this testimony in the Willingham case without ever having met the defendant.)

And secondly, in spite of the declarations of some of those involved, the Willingham case is about something bigger than the questions of his specific conviction; it is about the freewheeling manner with which the state of Texas specifically and the United States generally is willing to execute people. "This never was about the death penalty," insists Dr. Gerald Hurst, the Cambridge-educated chemist, but it is; if there is a chance, even a remote possibility, that mistakes like this can be made--and clearly there is that chance, as we've seen not only in Incendiary, but in The Thin Blue Line and The Trials of Darryl Hunt and the Paradise Lostfilms, and in all of the cases that haven't had the good fortune of having documentaries made about them.

As you can see, it is easily to get sidetracked by the issues raised by Incendiary and ignore it as a film, but then again, so much of the power of a film like this is in the skill with which it raises those questions and is inseparable from them. But let it be noted that the picture is crisply and confidently assembled, that Steve Mims's cutting is sharp, that Graham Reynolds's music is tense and effective. It respects the patience and intelligence of its viewers, particularly in its willingness to get down into the muck of the various meetings, complaints, and hearings. And it presents its final, infuriating bits of information without comment, because no comment is necessary. There are, as indicated, a few holes that prevent the film from presenting a complete picture--the absence of Dr. Beyler (who wrote the Texas Forensic Science Commission's report) is odd and worth explaining, some of "defense attorney" David Martin's questions are worth greater examination than given, and aside from Martin, there aren't enough voices from the original trial.

These are problematic exclusions. But they barely soften the film's considerable power and upsetting aftertaste. Yes, as mentioned early on, Incendiary: The Willingham Case is advocacy. But if an injustice was done, is advocacy wrong?

Jason lives in New York. He holds an MA in Cultural Reporting and Criticism from NYU.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||