| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Eclipse Series 32: Pearls of the Czech New Wave

For good or bad, I've derived much of whatever historical and international cultural context I might have to draw upon from the movies. Case in point: Phillip Kaufman's 1988 film adaptation of Czech novelist-intellectual Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being has little to do with a run of particularly daring, experimental Czechoslovakian films from the '60s that's often categorized as "the Czech New Wave," but it does provide some basic understanding of where those movies came from by depicting their historical moment, capturing some of the progressive, reforming political climate -- a newfound, post-Stalinist free spirit that swept Iron Curtain-bound Czechoslovakia in the mid-'60s-- that surrounded them. I therefore had Kaufman's helpful images (however fictionalized and dramatized) in my mind as contextualizing background, a mental picture of the short-lived cultural window -- a several-year thaw before the "Prague Spring" of the 1968 elections and the almost instantaneously redoubled Soviet oppression that followed -- through which the films in Pearls of the Czech New Wave, a new box set from the Criterion Collection's Eclipse Series, were able to slip. In a neatly consistent narrative of singlehandedly reintroducing an entire continent's cinephiles to Czech cinema, it was Criterion that first provided us with Kaufman's indirect entry point, along with the chance to add peak Czech New Wave exports like Milos Forman's Loves of a Blonde and Jiři Menzel's Closely Watched Trains to our DVD libraries. Now, with Pearls of the Czech New Wave, they're offering the deepest and most thoroughgoing survey yet of a film movement often cited for its vitality and importance, whose long-running lack of availability on home video (at least in North America) this release is a huge leap toward remedying.

The set collects the work of five filmmakers -- Vĕra Chytilova, Jan Nĕmec, Evald Schorm, Jiři Menzel, and Jaromil Jireš -- who cut their teeth at the FAMU film school in Prague, and their recognizably Czechoslovakian subject matter, characters, and themes they share, along with their distinctive individual filmmaking approaches, are presented to us all at once through the first film in the box, the five-part 1966 omnibus Pearls of the Deep, wherein each one of them takes on the adaptation of a short story by Czech literary master Bohumil Hrabal. In Menzel's Mr. Baltazar's Death, an alternatingly deadly-dry and lyrical tone is taken in depicting the day trip of three bourgeois motorcycle fanatics to a big race that most spectators seem to regard as a form of blood sport (with the notable exception of a couple of beautiful young lovers, one thing uniting most of these films being a reflexive sympathy for youth and a suspicious disdain for calcified, old-timey people and ways); in The Impostors, Nemec takes a bitterly funny look at two boastful old, terminally ill men on a hospital ward whose grandiose self-mythologizing as, respectively, a legendary journalist and renowned opera singer, is belied by the sharp-tongued, efficient men who subsequently perform their autopsies and mock the falsity of the two dead proles' final, comforting invention of nonexistent past glories; Schorm's The House of Joy is a progressively more surreal, strange farce (the only section of Pearls of the Deep shot in color) about an eccentric old peasant and his even more eccentric, even more elderly mother, whose unbounded artistic impulses suck two visiting National Insurance salesmen -- efficient, official, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed bureaucrats -- back in time and out into rural idiosyncrasy in a way that makes their (and our) heads spin, with a bizarre yet lovely fast-mo flashback offered by Schorm as one of the most technically adventurous touches of the film; Chytilova's The Restaurant the World has its own beautiful, speed-altered interlude as a young bride whose husband has been arrested at their wedding party and an artist with a suicidal girlfriend whose modern artworks are misunderstood by his factory comrades lead each other astray (or is it into one last, precious, fleeting, frightening moment of freedom?) for an erstwhile wedding night; and finally, Jireš's cinema vérité Romance contrasts the idea of romantic adventure suggested to its young male protagonist in Prague cinemas (Fanfan la Tulipe is what he's just seen) to the kind of love actually available to him, in this case a sometime-prostitute Gypsy girl whose family is part of an oppressed, poor ethnic minority, whose side Jireš takes in a sharp, witty, and poignant climax.

The next disc contains feature films from two Pearls of the Deep alumni: Vera Chytilova's Daisies and Jan Nĕmec's A Report on the Party and Guests, both also from 1966. It would be premature to claim that Daisies is the "best" film of the set, but it is the most immediately striking. Shot in color, it's the story of two girls, apparently in their late teens or early twenties, whose exuberant self-professed "spoiled"ness results in an insouciant, psychedelic, pop-art trip through contemporary Czech life from the POV of thrill-seeking youth with insatiable appetites: these girls eat, drink, pose, pout, idly philosophize, and generally make merry amid the extra-bold, space-and-time-warping world Chytilova creates for them to galavant through, which incorporates Warholian/consumer-culture visuals with its bold, bright colors and some formally very audacious editing (sometimes causing the image to momentarily become rapidly transmutating, kaleidoscopic collages). One gets the feeling that Chytilova has had exposure to Godard's on-the-fly, anti-realist hyperinventiveness (e.g., Pierrot le fou, to whose two young people on the lam Daisies's protagonists bear a passing resemblance) and allowed that iconoclastic spirit to guide her as she created her film, which releases all the bottled-up energy of a youth excluded for too long from a new culture, drifting in surreptitiously from the West and designed just for them (and, as an added bonus, confounding and exasperating their staid elders).

While Chytilova seems to have tapped some of that Godardian energy for herself, Nĕmec's film, with its poker-faced, naturalistic style; absurd, frightening, disorienting events; and the director's taut observance letting the suspense just simmer slowly to a boil, plays something like the missing link between Bunuel's The Exterminating Angel and Michael Haneke's Funny Games. A group of middle-aged, middle-class types from the city are visiting a wooded estate, attending the birthday celebration of a powerful friend (or, perhaps, boss or leader) when they are taken hostage, with a mixture of tongue-in-cheek teasing and queasy-making menace, by a group of young men with a supercilious thug for a ringleader. As it turns out, though, both these miscreants and the wedding party the confused older group has seen traipsing through the woods from afar are somehow connected to their supposedly benevolent, upper-crust birthday boy, whose party is interrupted when the one thoughtful, quiet, reserved member of our original group of well-wishers decides to opt out of this unsettling get-together and simply leave; everyone seems to agree that he must be found and reclaimed, and the hunt is on. I don't know how literally the title was translated into English, but this "report" on the "(P)arty" would seem to have something allegorical/satirical to say about the hierarchy and practices of the all-powerful Czech Communist Party. In any case, Nĕmec's well-executed stylistic strategies conspire to render its discombobulating sense of threat palpable and indelible.

The set's third disc is Evald Schorm's 1967 film The Return of the Prodigal Son, which follows along for a while in the travails of a young man called Jan (Jan Kačer), who, though smart and successful, with a good job and a beautiful wife and child, suffers from a depression that keeps landing him back in the remote, peaceful asylum/retreat where most of the film takes place. There, Jan befriends a young male ballet dancer even more tortured than he and is preyed upon psychologically and sexually by, respectively, the institute's head psychiatrist and his dissatisfied, yearning wife. Meanwhile, Jan's own wife carries on an affair with a mutual friend whom she doesn't love but who "needs" her in a way her husband, whom she genuinely loves, does not. Schorm's approach to Jan's story is reminiscent of Bergman in its fraught-yet-quiet intimacy, and of Cassavates in the improvisationally played, realistically unpredictable interactions between characters. Kačer cuts an iconic figure as Jan, who, with his existential malaise, his black turtleneck, and seldom-removed, Lou Reed-like black shades, offers a darker, more disaffected contrast to the pop-art flower children we got to know in Daisies.

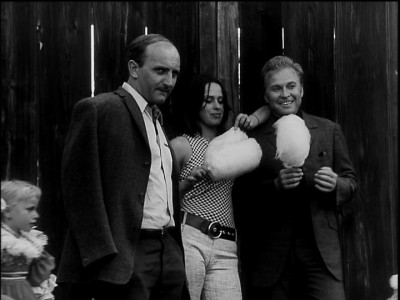

The set comes to a close with its fourth disc, a double feature of Jiri Menzel's Capricious Summer (1968) and Jaromil Jireš's The Joke (1969). Capricious Summer lives up, visually and narratively, to its evocative title, depicting three aging men -- a Canon (senior church cleric), a general, and a major, for a sort of cross-section of a particular kind of contentious old Czech coot -- at a summer retreat run by the general and his wife. The risible triad's routine of ongoing, exaggeratedly heated and arcane little arguments about religion and politics, along with the general's attempted infidelities with the younger female guests of the camp, is interrupted and thrown off its amusing (for us) yet drearily repetitive (for them) course by the arrival of a sort of traveling circus/magic show starring a handsome young magician/tightrope walker and his lovely girlfriend/assistant. The general's work-hardened wife develops a subservient, motherly crush on the young man, while the three older men all have a go at the comely lass. But these are two different worlds; the joyous, sexy, sardonic, Felliniesque circus life is just a temporary reprieve landing briefly in the midst of the older residents' routines and the summer's capricious, more often than not rainy (which makes for some gorgeous visuals) weather. With delicate, near-painterly framings and color photography by Jaromír Šofr, Menzel effortlessly takes the story from bawdy farce to melancholy reverie on the changeless cycling of the seasons and the inevitable, mortality-evoking progression of time and comes up with something bittersweet and reflective -- a sadder, more resigned, and unexpectedly touching companion to Bergman's Smiles of a Summer Night and Woody Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy.

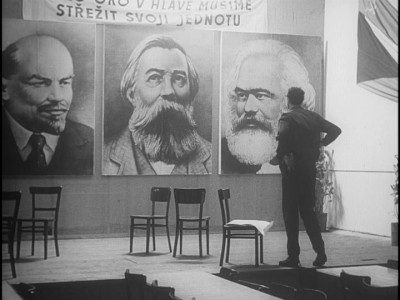

Closing the loop begun with my initial Milan Kundera/Unbearable Lightness of Being point of reference, The Joke is also a screen version of a (much earlier) Kundera novel, adapted here by Kundera and director Jaromil Jireš. The writer and director spin the tale of a middle-aged man betrayed by his university comrades in 1949, when they unanimously voted to expel him from the school and send him off to prison for the seditious act of writing a "cynical" postcard to his Party-stalwart girlfriend, in which he mocked the naïve optimism of the Young Communists and praised the way-out-of-favor Leon Trotsky. Those events come to us in flashbacks; the film's present finds our protagonist, Dr. Ludvík Jahn (Josef Somr), in the late-'60s now, after he has been allowed to return to civil life during the post-Stalin thaw. As a successful member of the community, the doctor is interviewed by a chirpy, inane woman (whose questions discreetly avoid where he has disappeared to for 15 years), incidentally realizing that his interviewer is the wife of the close college friend whose treachery cut him most deeply, he plots to avenge himself by seducing her. He is sobered to learn, however, that changing times and opening minds have rendered such gestures futile, meaningless; everybody has renounced and longer wants to remember anything about, let alone take responsibility for, the era in which his horrific experience has stranded his own feelings and responses toward the world around him. The doctor is a victim of history, which has unjustly robbed him of 15 years and then, to add insult to injury, skipped nimbly ahead without him, stealing away any meaningful or fulfilling target for his revenge. Jireš's film, cleverly and skillfully wrought as its flasback/flash-forward transitions are, is the most dramatically straightforward and directly historical/political of the bunch -- a fittingly mordant, anguished, and pointed cry of protest, one last gasp before the Czech New Wave and the liberated social and political currents that had buoyed it were laid to rest by the '68 Soviet invasion of the Czech capital -- the ominous black cloud that would put a violent and permanent end to the Prague spring.

Calling these films "pearls" is obviously a reference to the all-inclusive collaboration of their directors, Pearls of the Deep, with which the set (and, on some ways, the movement itself) kicks off, but the aptness of that characterization goes far beyond the punning reference. Because they all come from the same period and place, the sand in their oysters -- the environment of agitation and resistance that provoked and inspired -- was the same, leading to some commonalities in attitude and theme over the six works. But each of these films has been formed and shines in its own unique way; the differences are at least as fascinating, compelling, and aesthetically striking as what ties them together. Some may glow a bit more brilliantly than the others (at least on the first viewings, Daisies, Capricious Summer, and The Joke are particularly exceptional), but collected and strung together as they are here, they make for a grouping of adventurous, alluring experiences that complement and play off each other in a way that feels just right. These selections collectively represent, in an in-depth and far-ranging way, a burst of creative energy in the history of world cinema unlike any other -- one that we can be thankful to be so eloquently reminded of with the appearance of the well-curated, revelatory cinematic cornucopia that is Pearls of the Czech New Wave.

THE DISCS:

In keeping with the Eclipse Series tenets -- bare-bones editions of important but difficult-to-find films -- the transfers, all in the original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, vary from fair to good in quality, and a thorough and complete restoration job has not been done, meaning that there are signs of print wear, debris, and flicker noticeable off and on throughout. (There is also what appears to be an oddity of film speed or projection -- perhaps in keeping with the way the films were made -- in both Pearls of the Deep and Return of the Prodigal Son, which makes some of the scenes seem to play out in slightly slower motion than normal; this is not, however, distracting or aesthetically displeasing, though it's difficult to tell whether it is a quality innate to the source materials or not.) The picture quality is consistently at least acceptable and usually better than that throughout, with no truly unforgivable flaws to mar the visual experience.

Sound:Each of the films is presented in its original mono via a Dolby Digital 1.0 soundtrack (in Czech with optional English subtitles.) The original sound quality is solid (and occasionally, it appears, post-dubbed for the dialogue), and its transfer for presentation on disc sounds as faithful as possible to the original sound -- clear, consistent, and almost entirely unmarked by any hiss, pops, or crackling from sound deterioration due to age or wear of the print.

Extras:Eclipse Series releases are technically supposed to be bare-bones and supplement-free, but as usual, that's not 100% true: Each film has an insert or liner notes by Criterion staff writer Michael Koresky that offers excellent background on the filmmakers; the heady, unexpectedly free time and place in which they made their work; and the film-school milieu they came out of, as well as brief but astute observations on and interpretations of the films themselves.

FINAL THOUGHTS:They've dipped their toes well into the Czech New Wave waters before -- with their releases of Milos Forman's Loves of a Blonde and The Fireman's Ball, Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos's The Shop on Main Street, and Jiři Menzel's Closely Watched Trains -- but Criterion dives deep for their Eclipse Pearls from the same movement, and they've come up with an assortment of magnificent specimens that are invigorating all around and include at least a couple of truly great, brightly polished examples of what a sudden onrush of artistic freedom and political defiance gave rise to in Czechoslovakia's incongruously robust Soviet-bloc film industry in the 1960s. The films they've gathered together are a captivating, roundly engaging reminder that no national cinema or its New Wave is monolithic; there is certainly a mordant humor and a sociopolitical/historical context that these works all share, commonalities one can spot that tie them together, but what's most interesting about all the cinematic voices represented in Pearls of the Czech New Wave is how divergent and distinctive they are. Whether it's Jan Nĕmec's poker-faced, unsettling surrealist satire A Report on the Party and Guests; Jiři Menzel's delicious conjoining of the bawdy, the melancholy, and the exhilaratingly beautiful in Capricious Summer; the true '60s aesthetic and social radicalism on gorgeous display in Evald Schorm's Return of the Prodigal Son and Vĕra Chytilova's Daisies; or the wizened, rueful encapsulation of decades of political turmoil in Jaromil Jireš and Milan Kundera's The Joke, the set represents one uniquely brilliant and bold approach after another to the narrative and poetic possibilities of cinema. The Czech New Wave is often discussed in cinephile circles, but unlike its French, German, and recent Romanian counterparts, it has until now gone frustratingly underrepresented on home video in North America; this generously well-rounded, important release is thus nothing less than the gratifying, long-delayed insertion of a vital missing piece into the never-ending jigsaw puzzle of any serious movie lover's exploration of world cinema. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||