| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

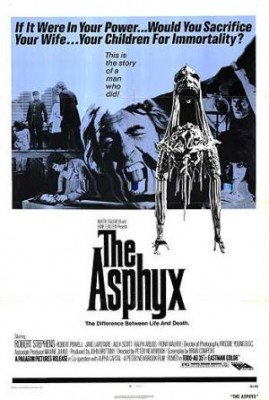

Asphyx, The

There were attempts to change with the times. Actor Christopher Lee, disheartened by the increasingly trashy films he found himself in, formed his own production company with the intent of making more adult, more literary films. The result, Nothing But the Night (1972), was an intelligent, above-average film that unfortunately failed commercially. Lee later starred in Hammer's last-ditch attempt at something bigger and better, To the Devil - a Daughter (1976), an interesting effort ruined by shaky financing, bad luck, and ineptitude.

And Lee also co-starred in The Wicker Man (1973) the best and most famous of the post-boom British horror films, but the main creative forces behind that project weren't horror movie specialists. The same applies to The Asphyx, a film directed, photographed, and starring talent mostly new to the genre.

This lack of inexperience and unfamiliarity with the genre both helps and hurts The Asphyx. Superficially, it closely resembles a Hammer Gothic but its strengths and weaknesses are completely different. It's undeserving of its almost total obscurity, though it's not a complete success, either.

Licensed from Euro London Films this Redemption Films/Kino Lorber release is positively gorgeous, featuring as it does a peerless 1920 x 1080p transfer from the original 35mm negative. The exquisite lighting and cinematography are The Asphyx's main asset, and this Blu-ray presentation offers viewers the first real chance to fully appreciate the film since its very limited theatrical run back in 1973-74. (More on this below.)

In late Victorian England widower, philanthropist, and amateur scientist Sir Hugo Cunningham (Robert Stephens), who dabbles in photography and psychic research, plans to remarry. He introduces his fiancée, Anna (Fiona Wise, I, Claudius), to his relieved adult son, Clive (Ralph Arliss), and daughter, Christina (Jane Lapotaire, the play Piaf), the latter herself contemplating marriage with Giles (The Survivor's Robert Powell), a one-time penniless orphan adopted into the wealthy Cunningham family.

Sir Hugo has stumbled onto a curious phenomenon. Dark smudges appear on still photographs taken of terminally ill people near death. He theorizes that the images he's captured are of the soul departing the body at the moment of death.

Later, he begins experimenting with an early motion picture camera, but while photographing Anna and Clive punting on the estate's lake, there's an accident and both drown. Inconsolable, Sir Hugo several weeks later decides to project the film he shot of the accident, and is shocked to see the blur actually enter rather than exit Clive's body. (Newbrook makes a mistake common in movies showing such scenes. Though Sir Hugo films them at a distance and with a single camera, the newly developed raw footage suddenly cuts to a tight close-up of Clive's head striking a tree branch.) This entity, which Sir Hugo calls The Asphyx (after the ancient Greek spirit), is essentially Death itself, Sir Hugo further theorizing that if he could somehow capture and contain a person's Asphyx, they might well live forever.

The Asphyx was the only film directed by Peter Newbrook, a camera operator on some of the most famous British films ever made, including Scott of the Antarctic (1948) and most of David Lean's later films: Hobson's Choice (1954), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). As a full DP he had less success, and his career was stalled in lower-budget (if sometimes interesting) films like That Kind of Girl (1963) and Corruption (1968). He produced the latter, along with several other minor horror films (Crucible of Terror, Incense for the Damned) before tackling The Asphyx.

For The Asphyx Newbrook hired the great cinematographer Freddie Young, who'd been the DP on Lawrence of Arabia and whose credits included 49th Parallel (1941), Treasure Island (1950), Lust for Life (1956), and You Only Live Twice (1967). Young was coming off two huge films, Lean's Ryan's Daughter (1970) and Franklin Schaffner's Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) but evidently wasn't averse to smaller, interesting projects. He had, for instance, shot the memorable monster movie Gorgo a decade before this.

Visually, The Asphyx is beautiful. The film's budget probably wasn't significantly higher than other British horror films of the period, but it's far more delicately lit and photographed than the typical, rudimentary techniques employed in other '70s horror pictures. However, as beautifully lit as all the sets are, Newbrook's direction is singularly inert. The film, already on the talky side, is often photographed proscenium arch-style, with actors moving into positions as if preforming before a live audience.

The Asphyx, as superimposed into the film, is an unsettling, unique movie monster, a kind of writhing, unearthly Muppet. It's quite creepy (Muppet-style manipulation notwithstanding), and though never clearly visible the filmmakers seem to have decided to show more of it than originally intended. The dialogue never describes it as anything more than a vaguely defined apparition, and certainly never as a monster.

The film's ideas are subservient to its look, to good and bad effect. Mad scientists in movies are often motivated by a desire to bring a beloved wife back from the dead, but The Asphyx puts a unique spin on this well-worn concept, though it doesn't develop it as well as it might. Sir Hugo is a widower whose last chance at happiness is thwarted in a cruel accident that robs him not only of his fiancé but also the son groomed to take his place. More tragedy follows and his obsession to become immortal has less to do with benefiting mankind or turning tragedy into something positive than, ultimately certainly, about self-flagellation, penance for causing death, and even merely surviving one's children.

Robert Stephens's performance is similarly theatrical. Primarily a stage actor at this point, his movie roles became more important as the '60s ended, notably in Romeo and Juliet (1968) and especially The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969). He was brilliant in his next film, playing the title role in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970), but he and Wilder didn't get along, and under such strain Stephens suffered a career-crippling nervous breakdown. He began drinking heavily (he's a good 25 pounds heavier in this), resigned suddenly from the National Theater, and his marriage to actress Maggie Smith (his Jean Brodie co-star) was on the rocks. Accidentally, he was a good choice to play the tragic patriarch of a doomed family.

The Asphyx bears a passing resemblance to The Private Life of a Sherlock Holmes. Stephens taps into the same melancholy, and both films feature prologues set in present-day Britain, followed by main titles over dusty personal mementos from 70 years before.

Newbrook's lack of experience directing horror films - those he produced were similarly unusual but not good - probably accounts for several bad ideas that work against the film's effectiveness. Besides the stagy blocking, Brian Comport's screenplay, based on a story by Christina and Laurence Beers, has myriad clunker lines that sound especially ridiculous coming from Stephens's florid line readings, e.g., "I want you to summon up my own Asphyx!"

Then there's the awkward manner in which Sir Hugo brings himself and others close to death in order to awaken the Asphyx: Sir Hugo straps himself to an electric chair, and later subjects his own daughter to a homemade guillotine. Surely there are less unpleasant ways to arouse an Asphyx? Immortality is likened to indestructability, but avoids obvious questions about the impact of aging, diseases, and injury on a body that cannot die. The low budget also damages the film: a climatic explosion and grotesque make-up (actually a mask) at the end are unpardonably inadequate.

Video & Audio

The Asphyx is presented in an 86-minute U.K. release version cut. Included, as an extra feature, is the reconstructed 98-minute American version, which enhances some ideas but which is also a lot draggier. The added scenes in the longer version are presented in standard-def and visually are much inferior. David Kalet's All Day Entertainment previously released the long version to DVD in 1999, and his efforts clearly paved the way for this release. The picture was shot in Todd-AO 35, a Panavision/CinemaScope compatible process. The 2.35:1 image is stellar, extremely sharp to the point of comparing favorably to large negative format movies on Blu-ray like Battle of the Bulge and It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Colors are rich and true, with especially impressive golds and reds.

The credits as well as trade ads reference a 4-channel stereo process, Super Quadraphonic Sound, presumably compatible with four-track magnetic stereo, but the film is 2.0 mono only, as was the previous DVD release. No alternate language or subtitle options.

Extra Features

Supplements, in addition to the longer cut (see above), include an up-res theatrical trailer for the U.S. version, along with high-def ones for Virgin Witch and Killer's Moon, which if nothing else make a good contrast with The Asphyx in terms of lighting and cinematography. Also included is an unusually good photo gallery.

Parting Thoughts

A real aberration, The Asphyx's main draw is its lighting and cinematography, and this Blu-ray shows both to outstanding advantage. The movie is very interesting in other ways and Highly Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is a Kyoto-based film historian whose work includes film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features. Visit Stuart's Cine Blogarama here.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||