| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Route 66: The Complete Series

Reviewer's Note: Over the years I've had the pleasure of reviewing the various seasons of Route 66, so for this new Shout! Factory series release, I'll port over my thoughts from those previous reviews, along with new details about this terrific disc set.

Arguably the best drama anthology of the 1960s, and Shout! Factory, that champion of vintage television, has put it all together into one neat little package, you highway ribbon wanderers, you existential soul-searchers. Route 66: The Complete Series has, for the first time ever, all four seasons of the iconic classic, Route 66, starring Martin Milner, George Maharis, and Glenn Corbett, neatly tucked away on 24 discs―that's all 116 episodes from its original 1960 to 1964 CBS run. I'm not sure if Roxbury/Infinity (who previously owned the DVD rights to the series) ever released the fourth season of the show, but the transfers used here (or at least the original materials available for Shout!'s transfers) look to be the same ones utilized in the Roxbury editions―thankfully with no "faux widescreen" gimmicks of previous sets, either (and Shout! labeled up-front one of the two episodes that appear to be edited for syndication here). Extras are minimal (no commentary tracks, unfortunately), but content is as strong as you can ask for in what is, simply put, one of the finest drama series ever to show up on the network schedules―and that's more than enough to earn our highest rating here at DVDTalk.

Straddling the time period (as well as the psychological and sociological road map) that lies between Neal Cassaday's and Jack Kerouac's travels chronicled in On the Road, and the coming counterculture hippies Wyatt and Billy of Easy Rider who dropped out of society altogether, Route 66's existential wanderers Tod Stiles (Martin Milner) and Buz Murdock (George Maharis), and later Lincoln Case (Glenn Corbett), occupy a most unusual place in big network TV of the early 1960s. Whereas in The Fugitive, Dr. Kimble was forced to flee across America because of a bogus murder rap (while connecting with various souls in trouble), Tod and Buz willingly flaunt the conventions of society (or at least "TV society) that expected young men like themselves to settle down and raise families, and to help maintain "the American Century" through their own industry and right living. The only other male characters on TV at the time who lived as free and easy as that were the cowboys of all the Westerns saturating the airways; however, their "period" context safely relegated them to the past and thus beyond our culture's increasingly conformist consternation.

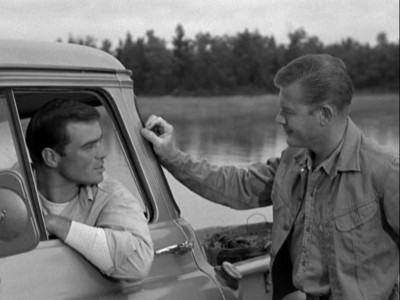

Buz and Tod, though, were having none of that pressure to "fit in." Buz, a tough orphan who grew up in the hard-scrabble world of Hell's Kitchen, and Tod, a well-heeled prep school attendee whose comfortable world came crashing down when his beloved father died, leaving him penniless (except for that totally sick 1960 Corvette), have no thoughts about marriage, no thoughts about putting down roots, and only go where the next bend in the road takes them. It's not even clear, as Buz alludes to in the premier episode, if they're even looking for anything. They just have to move, to be free, to get away from the garbage of the city (Tod's father ran a barge on the filthy East River, where Buz crewed during summers) and to feel the wind in their faces―a fundamentally American desire made easy by that sweet, sweet Corvette convertible. It's important, too, that both are fatherless; that rigid rudder of emotional stability (or instability, depending on the author) in most American fiction and storytelling―the father―is absent here (Linc, too, has a strained relationship with his dysfunctional father). Even though Tod is stricken by the memory of the loss of his father, the gift of the Corvette has given him means to explore America his way, with no strings attached. There's no one to go home to for Tod and Buz; that car is their home, endlessly prowling the great ribbons of highways and back roads that crisscross the country. And their "family" are the various dreamers, loners, losers, and broken victims whom they encounter along the way.

Despite the fixation many fans of Route 66 have for what they consider the "real" star of the series―that beautiful Corvette, with new models helpfully (and rather illogically) provided for each season by show sponsor Chevrolet―the episodes' location work is perhaps the real star of this series. Few if any network television series at that time actually shot on location, and fewer still shot inside real environments, such as run-down diners, real hotel rooms and rooming houses, oil rigs, and fishing trawlers. But Route 66 did (co-creator Herbert Leonard stated only a handful of sets were ever built for the show, and only then if inclement weather forced them to abandon the location), giving an unparalleled view of early 1960s America that can now serve as a documentary newsreel of the times. This hyper-realistic attention to authentic, evocative verisimilitude is further enhanced by the sometimes rough nature of filming, with naturalistic lighting and occasionally tinny sound (from filming in those cramped rooms) giving Route 66 a tone and a feeling unlike any other network TV show from that time.

Of course, once the boys light somewhere for gas, or car repairs, or to work to earn food and gas money, Tod and Buz are immediately drawn into the lives of various colorful strangers, as befitting any proper anthology series. Romance was often a catalyst for involvement, but often as not, it was Tod and Buz's innate curiosity to experience life, and their genuine warmth and compassion for others that came through, giving the supporting characters a reason to trust and confide in them. Not that compassion and warmth didn't come without fisticuffs every now and then (Tod and Buz, bless their pre-P.C. hearts, would often resort to violence when talk failed). The series, created (with Herbert B. Leonard, who supervised the episodes' editing) and written almost exclusively by that terrific Hollywood screenwriter, Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night, The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure), is uniquely focused on a compassionate exploration of the lower rungs of American society―perfectly embodied by Buz―and nicely cross-reference by Tod, who was born to money, only to find it gone just as he enters adulthood (Route 66 didn't just look at the "losers," it also looked at "winners" by society's standards, who were flipping out just the same). Silliphant, known for his liberal social outlook, comes squarely down on the side of the day laborers, the farmers, the shopkeepers, the oil riggers...and the neglected. But he's layered enough as a writer not to lionize these characters just because of their positions (no "noble proletarian" b.s. here); their faults and foibles are fully on display, and often, the very fact of their reduced circumstances (both material and psychological) precludes meaningful emotional growth or successful relationships―that is, until Tod and Buz wheel into town.

Even with all that authentic location work and heavy thematic concerns, there's certainly an element of fantasy to Route 66; it's doubtful two clean-cut-looking "kids" like Buz and Tod (youthful appearances aside, Maharis was 32 when production started, to Milner's 29), driving that expensive, flashy car, would be so readily accepted within some of the circles they find themselves (although Silliphant is careful to have his supporting characters believably suspicious of their motives at first). And conventions of the anthology drama still creep in at this stage, with stock characterizations and situations (the premiere episode is almost a direct lift from Bad Day at Black Rock, for example) present to keep the viewer grounded. Obviously, the realities of life on the road for two young, healthy guys aren't shown, either; when Buz and Tod take a girl out, they're likely to have their jackets and ties on, and the girl goes home, unsullied, before midnight. As for poetic Silliphant, frankly a master of the perfectly realized episodic TV script, he can wrap things up a tad too neatly with the sticky situations that pop up. Ultimately, though, that's the beauty of Route 66, despite the trappings of cinema verite locations and shooting methods, and gritty scripts that deal with nuclear holocaust, WWII atrocities, and spousal abuse (and seemingly endless stories of estranged fathers and sons). Route 66, in the end, is allegory, not reality. And escapist allegory, at that. When composer Nelson Riddle's driving, pulsating theme song (arguably the best remembered element of the show) surges up on the soundtrack, the big brassy bridge exploding over images of Tod and Buz laughing as the wind whips their hair back, that's the element that viewers respond to most primally in Route 66: the open road, and the promise of freedom. Not at all unlike the real pull of that similarly subversive series, The Fugitive, the dramatics and strife and emotional pain that the supporting characters suffer only makes the romantic appeal of Tod's and Buz's lonely journeys that much more sweeter. After all, the viewer knows that Tod and Buz can just pick up and leave at a moment's notice if things really get out of hand (they have to: it's a weekly series). And once they help heal these broken people, they skip on out, moving on to the next town, while the people they connected with go through the messy process of realigning their lives discreetly off-camera. Allegory serves romanticism in the guise of escapist entertainment.

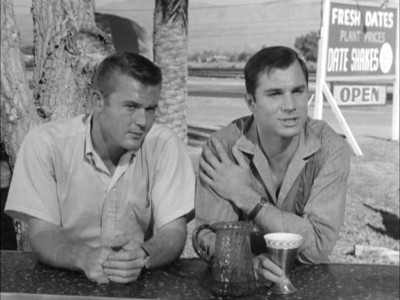

But all the location shoots and tightly written scripts in the world wouldn't make Route 66 work, if the casting of the two leads failed. And Route 66 found two performers whose different personalities and approaches to acting perfectly meshed to create that certain indefinable "chemistry" that makes or breaks shows like this. Fresh, freckled-faced Martin Milner, clean-cut in his Pendleton shirts, with an easy grin and a determined "good guy" image, is earnest and ever-so-slightly wounded, with his backstory containing two common tragedies in American serial drama: he lost his loving father, and he lost all his family money. Mercurial George Maharis, all dark, brooding handsomeness, quick with the tough jive talk when confronted by various local goons and rough guys and yet sensitive and responsive to human frailties, is the perfect well-groomed rebel that the teen girls of the early 1960s would readily have swooned over. Maharis, certainly closer to method acting in his approach, fits nicely against Milner's steadier, more straight-ahead thesping, creating a marvelous dichotomy that bounces off each other in their frequent dialogue scenes (more about the arrival of Glenn Corbett and the resulting tone of the series later). Milner would go on to score true pop culture iconography in his long run on Jack Webb's Adam-12, and Maharis would leave Route 66 later in its run to pursue a largely unsatisfying film career (he's terrific as a thinking man's spy in John Sturges' The Satan Bug). But I think they've never been stronger than when they were a team, early in their careers (certainly another highlight of Route 66 is the absolutely stunning array of first-class actors, from iconic, famous faces like Joan Crawford, to many New York stage-trained actors as-yet largely unknown to television audiences, such as Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, and Robert Redford, filling in the various supporting roles, week after week).

Season Two of Route 66, while still loaded with excellent episodes, seemed to fall into that sophomore season trap of trying to maintain its original atmosphere, while dealing with the mechanics of keeping the formula fresh (it didn't help, either, that a major shake-up in the cast was coming at the end of this season, one that essentially dealt a slow but inevitable death-blow to the show). It's difficult to pin down precisely why this second season feels tentative, but the closest I can get to it is that while Tod's and Buz's first season adventures seemed to flow organically from the concept, in this go-around, these new travels seem to shore up the concept ("Okay, they're on the road...still...so what are they going to this week?")―an indication, perhaps, that the combination of Route 66' concept and message only really clicked when they were both new to the viewer. In the first season, Tod and Buz are hurting. Buz, perpetually angry and wounded, yet willing to embrace the wide open spaces of America, found a soul mate in Tod, whose introduction to the harsher aspects of trust and security was as abrupt as Buz's was protracted. And when they rolled off in their 'Vette in search of...whatever it was they were searching for, their adventures felt fresh and relatively realistic (or at least as realistic as they could be for a television show). Money was a constant concern, and the hard, manual labor they sought out accurately reflected not only their physical situation (two young drifters without a permanent address or references), but also their psychological orientation: hard, punishing, manual labor would help take their minds off their troubles. In fact, salvation could possibly be found in the "simpler" ethos embodied by that kind of basic, hard-scrabble lifestyle; there's no room for mendacity, false aspirations, and sickness of the soul due to the relentless consumer culture out there in those potato fields (uh...try living that way sometime and see how it really feels).

With the second season, however, we've already had that "newness of experience" with Tod and Buz, so their continuous encounters with equally damaged people in complicated, tense emotional situations, sometimes can feel...familiar. It's not that individual episodes are poorly written or executed; on the contrary, many are quite good―as good as many in the first season. But the resulting impact of the very concept of the series―that first adventurous striking out into the great, huge America to assuage the pain both travelers are feeling―becomes lessened necessarily by familiarity. The realities of a commercial network offering trumps the initially new, existential delight that Silliphant managed in his first go-around. The stories are still well-drawn in this second season, but that underlying explosion of new discovery is gone, taking away a lot of that indefinable "otherness" the first season of Route 66 effortlessly, almost spookily, conjured up, week after week. The occupations and situations become a little more exotic, a little more far-fetched (working at CBS's Television City, experimental speed boat driving, Buzz becoming temporarily blind, working at JungleLand and Pacific Ocean Park...which CBS partly owned, and perhaps most ludicrously, Buz, that rebel, becoming a junior executive for a large corporation), and the realistic, almost documentary gestalt of the first season, slips away. Finally, when Maharis begins his slow exit from the show, leaving Milner on his own for the final episodes, the spell is largely broken.

Producer/creator/chief writer Stirling Silliphant continues to explore themes and avenues of interest that preoccupied him during Route 66's first season. The dichotomy of unfettered personal freedom versus the necessary "grounding" as a result of committing emotionally to someone else, is prominently on display in several episodes. The excellent season opener, A Month of Sundays, featuring a stunningly beautiful Anne Francis in one of her best outings, is a good example, while in the perfectly modulated How Much a Pound is Albatross?, both Buz and Tod encounter a true "free spirit"―Julie Newmar, who rides around on a motorcycle, without a license plate...or a license for herself. Despite Buz and Tod's best efforts to win her, she remains resolutely free, attached only to her sense of discovery and independence (and her Zen philosophy―which was straight out of Silliphant's own personal lifestyle). It's a beautifully sad, funny, idealized portrait of the soon-to-be marketed "flower children" ("It's not easy being a pilgrim, or a rebel. But how else can you give yourself to life?"), one that again expresses Silliphant's need to explore personal freedom versus emotional commitment.

The notion of women unhappily trapped within their circumstances, both personal and societal―a relative thematic rarity for network offerings back in the early sixties―is also frequently explored here during this second season of Route 66. One of the best episodes this season, A Bridge Across Five Days, written by Howard Rodman, features Nina Foch in an absolutely mesmerizing portrayal of a mentally ill women returning to the world after years of confinement in a hospital. A quite literal translation of this recurring theme, the episode doesn't go for easy answers (even though the character does find some semblance of peace and self-awareness at the finale), discussing not only the character's own responsibility in getting the help she needs, but also the circumstances that helped put her in the hospital (a destructive marriage). In Blues for a Left Foot, written by Leonard Freeman, a former dancer is spiraling down into depression and isolation after her lover dies, a depression compounded by her self-doubts about her ability to stage a difficult comeback. As with many episodes of Route 66, despite some writers and historians assigning the series with a reputation for being strictly "liberal" in outlook and philosophy, Blues for a Left Foot has Buz yet again offering tough, hard, uncompromising advice for the floundering dancer (well played by Elizabeth Seal): "Take a look around you! The world is full of losers. It takes character to win!" It's a conservative pragmatism Buz has espoused before, and one that is at odds with today's devolution of "liberalism" into moral equivalency and victimization (I love it when heroin addict Robert Duvall, in Birdcage on my Foot, tries to excuse away personal responsibility for his addiction, with Buz then sneeringly running down a litany of societal and personal clichés for Duvall's actions, only to bat them all away with an indignant, decisive "So what!").

But while the majority of episodes for this second season are quite good, misfires do crop up, particularly towards the end of the season's run. Scripter Will Loren's To Walk With the Serpent is a grotesquely obvious (and poorly structured) rant on reactionary politics, while You Never Had it So Good vainly tries to justify the major character switch of having Buz suddenly amenable to being a hep-cat Man in the Grey Flannel Suit junior executive (a fairly torturous script from Silliphant that tries to have it both ways with the Buz character, to absolutely no avail). Go Read the River is a familiar work-out of the absent father/tortured child dynamic, made more uneasy by the relative illogic of Tod becoming a test driver for a highly secretive high-speed racing boat (the boat is that important to these multi-millionaires, who are worried about industrial espionage...so they go to an employment agency for a trained driver? Ridiculous). Even the well-regarded Stones Have Eyes may be poignant in spots, but how much is it reaching for Buz to be temporarily blinded so the screenwriter can highlight the troubles of the blind?

After these increasingly compromised episodes beging appearing in the second season, perhaps the "true" end of Route 66 comes with the last four episodes of this go-around. Reports vary according to the participants involved, but for whatever reasons, George Maharis began to inch away from the show at this point in the production, claiming a recurring bout of hepatitis that necessitated his absence from these last four episodes (while the producers claimed it was Maharis merely drumming up an excuse to eventually quit Route 66 to pursue his ultimately failed big-screen film career). Regardless of the reason, and despite the fact that Maharis would return for more episodes in the third season, before finally breaking away entirely in 1963, the aura of Route 66 was irrevocably altered by this change-up. Simply put: the series just doesn't work with Tod traveling alone in his Corvette. There has to be that ying/yang, push/pull opposition from the dark-haired, fiery Buz, and the outwardly patrician, more calm, cool and collected light-haired Tod, for there to be believable tension within the context of the revolving story lines. Besides, the journey began with both characters; taking away one with whom we've become emotionally invested merely points out that a certain phase of their journey for them―and for us―has ended, and can't be brought back. Sure, Buz showed up during Season Three...for awhile. But the realistic feel of the series suffered when these four episodes (which are quite poor in and of themselves) showed Tod either calling or visiting an unseen Buz (who supposedly was in the hospital). It felt fake, like a put-on, and when you couple that with the fact that the show's inherent interest was already inching towards repetition, those feelings don't go away.

...which just goes to show you that you shouldn't count your chickens. When Route 66 returned for a third season, despite the eventual walk-out by Maharis, creator/producer/head writer Stirling Silliphant, along with the show's other guest writers, managed to turn out a remarkable string of episodes for this 1962-1963 season. If the behind-the scenes production tumult involving George Maharis' defection this season did effect Silliphant, it doesn't show, because Silliphant has fashioned some of the series' best outings here―a fact that makes Maharis' departure all the more frustrating because it so obviously led to the eventual demise of the series. As usual with Silliphant's work on Route 66, one of his most prominent themes is the constant battle an individual wages over barriers (usually self-imposed) that thwart his or her efforts to realize themselves at their fullest emotional potential. Love, or more commonly, the lack thereof, is always two ends of the same circle for Silliphant. Love and understanding are what we strive for, even when we harm ourselves deliberately to push it away, and yet, love is also a commitment to another person that requires some degree of sacrifice to our ultimate individual freedom. With love for another person (and acceptance of ourselves, faults and all), we can't win for losing, but we can come to some kind of understanding and peace with the unresolved nature of life.

Silliphant had an uncanny knack for framing beautifully poetic-sounding passages about life and love and truth and beauty within his quirky, restless narratives (certainly as much a draw for fans of Route 66 as the format itself of two young searchers in a shiny new Chevy Corvette, exploring the vast America), a gift that gives many of Route 66 episodes an aural depth and complexity that was largely missing from most of the early 1960s' network television schedules. However, he wasn't above examining his own creation―these two existential American wanderers who sought something other than a Cold War 9-5 existence―in both serious and humorous ways, looking for flaws and contradictions that would keep the characters and dramas fresh and interesting. In this season's opening episode, One Tiger to a Hill, the first date between Tod and lovely Toika (Laura Devon) skirts dangerously close to Silliphant self-parody, as she rejects Tod's glibness in favor of wanting to keep her heart―a heart reserved for saving wounded people―unbroken: another one of Silliphant's tortured doves who long for freedom from possessive or disingenuous men. And when Tod, sailing out with Buz, rhapsodizes about the unknowable depths of existence that are mirrored in the endless cycle of salmon spawning and dying, the viewer almost sees a literal "Author's Message" card like the one that pops up in What's New, Pussycat?. But Silliphant, almost flippantly, has Buz immediately respond to Tod's description of the salmon's life with, "Monotonous, huh?" to which Tod laughs. Heavy-handed symbolism is acknowledged and punctured. The message is still there if you want it. It's valid. But you can laugh at the solemnity of it as delivered by a too-rapt Tod, as well.

Silliphant isn't afraid to show up Buz' weaknesses, too. Buz's penchant for angry, even vengeful judgment calls comes into play in Silliphant's Ever Ride the Waves in Oklahoma?, when he attacks, both verbally and physically, a drop-out surfer who shows little remorse for a kid from the sticks who killed himself trying to match his skills on the board. When humiliating Jeremy Slate about working as a busboy (on the beach, Slate is the "king") doesn't satisfy him, he takes Slate out and gives him a typical Buz pounding. But the harsh realities of the lesson fall on Buz, not Slate, who, bloodied but not at all broken, replies, "So you're up there. But what is that? You're just another wave I'm going to let pass. Something the wind blew in. Something that's going to break apart, and end up in foam. You're all done pounding on me, and what's it done for you? You can't get to me. Nobody can. I was strong enough to walk away from the whole gritty world. But you're locked in. You need the pressure. You've committed yourself way over your head. So go drown." As Buz says later when he admits the mistake of his arrogance about Slate, "I made him feel, but he made me understand." One of the series' best, Ever Ride the Waves in Oklahoma?, beautifully directed by Robert Gist (who gets the camera down low and tracking in some dynamic sequences), gives a small glimpse into the social dynamics that were just around the corner for young America, when even a committed wanderer like Buz looks positively tied-down next to a true drop-out like impassive surfer Jeremy Slate.

Other episodes in the first half of the season vary in overall quality, but clearly, the four episodes featuring Martin Milner without co-starrer George Maharis (during Maharis' second extended walk-out) are of most interest to curious fans, with Silliphant's A Bunch of Pagliaccis and particularly Shimon Wincelberg's You Can't Pick Cotton in Tahiti showing the series in good form...with the Tod character unfortunately treated as an afterthought. These could be entries in any dramatic anthology series; they don't relate strongly to the Route 66 format, as evidenced by Tod's peripheral participation. Were these episodes "scrambles" that had to be significantly when Maharis refused to show up for work? Or were they cobbled together at the last minute in response to no-show Maharis? In a way, it doesn't matter, because it's enough to say they don't work within the show's structure, because Route 66's structure is broken without Buz. Without Tod and Buz together, and without the actual physical comings-and-goings of that pair as they traverse the backroads of America, Route 66 is just another dramatic anthology: distinguished at times, to be sure―but not unique.

And like it or not, the public seemed set on having Maharis as Milner's partner. After the A Gift for a Warrior episode, Buz is gone for good and absolutely no explanation is attempted for his disappearance―a big mistake for a show that is supposedly about searching out the "truth" in life. Tod doesn't mention Buz to anyone; no phone calls to hospitals are made. Nothing. It's as if he didn't exist―a denial by the producers and writers that probably didn't sit well with loyal viewers. Curiously, in the next episode, Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain?, Tod appears to have a new traveling buddy: Lee Winters, played by none other than Robert Duvall. With zero explanation or background, Lee appears to have been traveling with Tod for some time; they're quite friendly with each other, and they banter like old pals. Shockingly, Lee even seems to have 'Vette privileges (he drives it!). Was this a try-out for Duvall as a potential co-star of the series (how wild would that have been)? Or an experiment in possibly having Tod cruise around with different co-pilots during his journeys? It's hard to say. But Duvall is only around for that episode before he, too, disappears without any explanation. A few Tod-only episodes follow, and then Glenn Corbett's Lincoln Cass is introduced.

I suppose it's inevitable that comparisons would be made between the Linc and Buz characters, with many loyal Route 66 viewers siding with Maharis not only because he began the series with Milner (and that opening alchemy of original players in a series has a powerful hold that doesn't easily allow for substitutes in the minds of TV viewers), but because of Maharis' charismatic performance, as well. Maharis did have that certain something that jumped off the small screen, giving Buz an edge, a danger, that contrasted nicely with Maharis' equally adept expressions of tenderness and existential angst. He played a jumped-up, hep cat out of Brooklyn who would not have been out of place in the various pieces written about the restless Beats who searched for meaning in a supposedly soulless America. And that nervy, jangly kind of energy balanced perfectly against the more wholesome, stolid of Martin Milner's Tod. As for Corbett...that potentially explosive, nervous energy is missing within this calm, too-sedate performer. Corbett is good at playing strong and silent, but that only gets you so far with the thematically and motivationally complex writing of frequent scripter, Stirling Silliphant. Corbett's handsome but relatively inexpressive face just doesn't register the level of searching and pain and unease―as well as the hipster flights of poetic fancy and sheer joy of being alive―that Silliphant's writing routinely requires of his wandering heroes (Maharis did it with aplomb).

Certainly series creator Silliphant gets kudos for introducing on television what has to be one of the earliest depictions of the coming emotional horrors that would plague tens of thousands of future Vietnam veterans, in the guise of Army Ranger Lincoln Case. In his introductory episode, Fifty Miles From Home, we learn that Lincoln not only served a tour in Vietnam, but that he was held prisoner there and had escaped after killing many of his captors (a traumatizing experience that leads to a pre-Rambo "Vietnam flashback" moment where Linc zaps a bunch of snot-nosed college kids for pushing him around). Later in the episode, he tells of a harrowing experience where he lost the woman he loved to the Viet Cong. That not only Silliphant but the CBS network was willing to put this kind of character on television in 1963, indicting not only "war" in general but specifically Kennedy's Vietnam, had to have been a quite daring political move for a weekly TV anthology to make at that time. Unfortunately, this potentially ripe character comes off as more wooden than mysteriously enigmatic under Corbett's listless thesping, undercutting much of the daring of Silliphant's conception.

That unfortunate factor, however, does not alter the fact that these remaining episodes of season three of Route 66 are just as fine as the first half of shows. Save for one or two acceptable but not exceptional episodes (The Cage Around Maria, Peace, Pity, Pardon), they are uniformly excellent, making the third season of Route 66―at least from a writing standpoint―the best of the series. As usual with Silliphant's work on Route 66, one of his most prominent themes is the constant battle between giving of oneself in love, and retaining one's individual freedom, and I can't think of a better example of this achingly bittersweet, temporary meeting of two lives destined to be parted, than Silliphant's The Cruelest Sea of All, which very well may be my favorite episode of the entire series. Tod and Linc find themselves working at Crystal River, Florida's world-famous attraction, Weeki Wachee, where spectators watch a spectacular underwater show where "mermaids" frolic in the crystal-clear springs. Tod works underwater, too, scrubbing clean the viewing windows, when he's not chasing after the various pretty divers who work as mermaids. Imagine his surprise, then, when gorgeous Elissa (Diane Baker) swims in from the springs and begins to poke around curiously at this "strange, new world." At first, Tod thinks Elissa is pulling some kind of gag to get a job, hinting at being "something" other than human to maybe enhance her chances, while pleasantly goofing on Tod and Linc. Later, he suspects she's another in a long line of damaged women he seems to encounter who hide in fantasy to avoid the complications and responsibilities of connecting with another human being. Linc, however, slowly begins to believe she may indeed be a mermaid, a notion confirmed by supervisor Donald McTaggart (Edward Binns), a wise soul who understands that we can hardly explain a universe that is incomprehensible on every level. Unfortunately, Tod realizes too late that Elissa is truly "of the sea" before she disappears.

I realize that to some readers, that synopsis sounds faintly ridiculous, especially considering the poetic-but-all-too-real shattering of illusions that underpins many Route 66 stories. After all, Silliphant is saying...mermaids are real. Ridiculous, right? Well...not the way Silliphant approaches the question. To Silliphant, Elissa's reality is unquestioned―it's Tod's reaction to her that begs the viewer's increasingly incredulous response: "How can he be so uptight and logical and unbelieving in the face of a gift so lovely and ethereal and precious?" I don't think anyone on television wrote better about lost, beautiful, crazy women than Silliphant, but Elissa is never in doubt about her own self. And Silliphant's delicate-yet-direct scripting for her makes the character seem, without a doubt, real. This isn't something silly and inconsequential like Splash!; Elissa is what she is: a mermaid. And her indescribably sweet, naïve introduction to the human world plays beautifully against the increasingly stiff neck Tod offers in response to her awakening. What Silliphant is getting at here is what Silliphant is always getting at to some degree in many of his love stories: the inability for two individuals to get their perceptions of reality in synch with each other, regardless of how much they may love each other. Silliphant's embrace of an "altered" reality―a world where mermaids do exist―isn't used comically or from a fantasy/sci-fi perspective at all, but as a means for exploring most fully one of his central themes: love does not conquer all when we refuse to accept alternate views of reality―something we may be incapable of doing, anyway. An indescribably sweet, tender love story, simply and unobtrusively directed by James Sheldon, The Cruelest Sea of All also features what I think is the lovely, vastly underrated Diane Baker's best performance. It's a turn constructed with utter simplicity and without the faintest touch of parody or spoof or self-consciousness on her part (there's a beautiful scene where gorgeous Baker, swimming underwater, comes up to the glass and kisses it where Milner is, that shows an unrestrained delight on Baker's face―with Milner laughing delightedly, as well).

A more "straightforward" version of this classic Silliphant conundrum comes in Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain?, where Lois Nettleton gives a truly bravura performance as the quintessential Silliphant "ghost woman," an existential, misfit who floats in and out of peoples' lives, without a past or a future, operating outside the strict conventions of early 1960s America. Tod is brazenly approached one evening by glammed-up Nettleton, who sweeps Tod off his feet...and then promptly absconds with his credit card, running up a $9,000 bill. Sure that he's going to have to sell his beloved 'Vette just to begin paying off this debt, he suddenly comes upon Nettleton working at a Skid Row soup kitchen...only she claims to be someone else entirely. Tod falls in love with this aspect of her fractured identity, too, before she claims to be a third person, telling Tod on a stage at the UCLA Drama Department, that in her world, certainties like "love" and "home" and even one claimed identity, are luxuries she simply can't afford, and that she's destined to be utterly alone, no matter who loves her, nor how deeply she is loved. As I wrote above, Silliphant had an uncanny knack for framing beautifully poetic-sounding passages about life and love and truth and beauty within his quirky, restless narratives, a gift that gives many of Route 66 episodes an aural depth and complexity that was largely missing from most of the early 1960s' network television schedules. And Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain? is a perfect example of his facility to engage in flights of verbal fancy while espousing some truly troubling certainties about the desperate uncertainties of life for those who can't or won't toe society's conventional line.

Which brings us to Route 66's fourth and final season, a perfectly respectable outing at times...marred only by the fact that Glenn Corbett is completely miscast for producers Goldberg and Silliphant's aims. The quality of the writing and direction (as well as the performances from the still-impressive casting) are certainly up to snuff...if perhaps less focused and pointed as previous seasons. However, there's no getting around the fact that Corbett simply can not give expression to the Silliphant's and the other writers' complex emotions. A rare simple example of this is Same Picture, Different Frame, a rather overwrought effort from Silliphant featuring Joan Crawford (far too old for the character) trying to avoid her psychotic ex-husband Patrick O'Neal. It's bad enough that Silliphant has a ravaged Crawford acting as if she still has the sexual prowess to either accept or turn away Linc's attention, but Corbett's truly inexplicable, robotic staring at Crawford in what I can only assume is so weird approximation of lust and pity, is laughable inept. Even worse is Corbett letting down a potential winner in Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are!, where lovely Diane Baker gives yet another layered, mysterious turn as a immature heartbreaker who knows she's going to ruin any man she meets. Alex Cord supports here, and he such an obvious jolt of energy next to the innervated Corbett that one longs to have had the producers suddenly slot Cord into that 'Vette and continue the rest of the season with him as Milner's partner (when static Corbett delivers some good Silliphant musings like, "Sure I move around a lot, but there's a difference: I'm not looking for myself, but for other people," you wonder what Maharis could have done with those lines). In John Lewis Carlino's otherwise excellent father/son story, And Make Thunder His Tribute, Tod and Linc offer up differing views of intractable raspberry farmer J. Carroll Naish's battle with life and his fed-up son, Lou Antonio, with Tod believing Naish's rages "rare and beautiful," and Linc saying they're "ugly and stupid." Later, both further elaborate through portraits of their own fathers, but whereas Milner perfectly delineates Tod's wistful, appreciative love for his equally loving father, Corbett's flat, automaton delivery about his abusive father is unemotional and unmoving.

It probably doesn't help that quite a few outings here don't have the usual keen edge one expects from the series, with silly entries like I'm Here to Kill a King (using the old "evil twin" cliché when Tod meets his doppelganger-turned-assassin, or the inconsequential A Long Way From St. Louie, with the brilliant Jessica Walters utterly wasted. There are memorable entries here, though, with scripter Ernest Kinoy's I Wouldn't Start From Here one of the series' all-time best. On their way to New York via Vermont, Tod's city-boy impatience gets the pair stuck out in the wilds, where wry, taciturn, whip-smart olde New England farmer Parker Fennelly eventually lets them into his life...only just, though. Linc immediately takes a cotton to the independent old codger, even vowing to stay with him to help him through one more brutal Vermont winter so Fennelly can keep his beloved horse team (he's too old to adequately care for them). What follows is a rather remarkable story of Linc trying too hard to hold onto a romanticized notion he has of Fennelly's life, while Tod casually falls for summer romance Rosemary Forsyth (incomparably lovely and effective here), a returning native who is avoiding a New York City fiancé she doesn't really care for anymore. At the end, the romance slips away, and Fennelly faces what Linc can not: getting old doesn't allow for denial, something the hardscrabble farmer probably learned a long time ago ("It's gonna get colder, and it's gonna get worse. And you just do the best you can. That's the thing about farming in Vermont. You break your back just trying to keep even with what's real. You don't have time to spare, fightin' your fancy,"). The final image of Fennelly leading his horses away is one of the most moving I've seen in Route 66; it doesn't matter that Corbett again isn't up to the story, or that later, the series ends on a rather ridiculous, ill-conceived note with the slipshod two-parter, Where There's a Will, There's a Way (the final goodbye scene between Tod and Linc is completely bungled: without grandeur, without sentiment, without note). That one episode with Fennelly is worth the entire season; who cares if Silliphant couldn't adequately wrap-up what was already dead to begin with. I guess it's like what departed Buz was trying to get at all along: it's the moment that counts, not the "whole."

The DVD:

The Video:

Shout! puts a disclaimer up at the head of A Fury Slinging Flame, indicating it was taken from the best available sources and has been edited for syndication (it runs about 45:00). However, no notice is up for Season Two's Blue Murder, which runs a suspicious 47:10. All the other 114 episodes run at 50 minutes or so, give or take some seconds, which is well within the confines of regular running times for that period (minus bumpers and episode promos). The transfers vary in fidelity; a few of the early episodes can be grainy and a bit contrasty, with picture noise that's heavy at times. But on the whole, the vast majority of episodes here look quite clean in their full-screen, 1.33:1 black and white transfers. Not bad at all.

The Audio:

The English split mono audio tracks for the various episodes vary, according to the original source materials, with some a bit low for levels, and hiss and pops present for many episodes. However, fans of vintage TV won't notice a thing.

The Extras:

A sixth disc on the fourth season set features some minor bonuses. First up is a 2003 episode of the documentary series, Great Cars, featuring the Corvette. It runs about 25:00 (some great vintage production footage of the iconic race car). Next, some vintage commercials for Bayer Aspirin and Milk of Magnesia (9:50), as well as vintage Chevrolet commercials, including one starring the cast of My Three Sons (15:27). Finally, there's a highlight reel from the 1990 Paley Center for Media festival for Route 66 (43:00), featuring George Maharis, Leonard Goldberg, Arthur Hiller, casting director Marion Dougherty, and Eliott Silverstein discussing the show. Interesting.

Final Thoughts:

Quite simply, the best television drama anthology of the 1960s. When existential wanderers Tod and Buz climb into that sweet, sweet Chevy 'Vette and blast down the American highway in search of...of whatever, a compassionate view of quintessentially American loners, losers, dreamers, and frustrated, lost winners, never before seen on network television, emerges. A series way ahead of its time, at times sad, funny, dreamy, and uncomfortably real. Brilliant work by all involved...until a mid-season cast switch spelled the death knell. Must viewing for anyone interested in vintage television. Who cares about the few iffy transfers and the minor bonuses? Route 66: The Complete Series, on content alone, earns our highest ranking here at DVDTalk: the DVD Talk Collector Series.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||